As museum educators, we often teach children to appreciate art as a method of self-expression, but we can also use it to engage them with challenging educational subjects. Research suggests there is educational value in interdisciplinary approaches that weave together subject areas while investigating a topic. A goal of mine has been to merge art and science themes, which have historically been viewed as unrelated subjects. However, artists are just as analytical as scientists are creative within their respective endeavors. Integrating these topics can provide a foundation for students to understand complex subjects, enhance critical thinking skills, and promote lifelong inquiry. To dismantle the divide, I’ve initiated experimental collaborations to teach science concepts through an art museum context while sparking creative thinking across disciplines.

As an educator at The Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, I believe in the importance of art and am constantly searching for resources to enhance art museum experiences for K-12 audiences. I found such a resource in the National Geographic Educator Certification initiative, a free professional development opportunity that introduces educators to the National Geographic Learning Framework. This framework has many commonalities with museum education: it seeks to broaden global understanding through observation, inquiry, and curiosity while empowering learners to communicate their knowledge through multiple expressions. Participating in the program also opened the door to an initiative that partners certified educators with emerging explorers. As a result, I embarked on an experimental collaboration with National Geographic Explorer and Madagascar-based paleontologist Harimalala Tsiory Andrianavalona, Ph.D, to develop STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Art, and Math) initiatives. I hope my story inspires other museum professionals to explore interdisciplinary collaborations and increase STEAM access.

Increased access to STEAM has great potential benefits to the world, in encouraging students to come up with improved solutions to global challenges. Dr. Andrianavalona and I worked together with that goal in mind, and sought to bring to light the commonalities between the artistic and scientific processes. In the program we developed, students conducted inquiry investigations of museum objects, developed questions, communicated observations, interpreted their observations through evidence-based reasoning, and participated in hands-on experimentation, problem-solving, and peer discussion. I discovered the importance of introducing students to experts in the field while giving them real-world application for their studies.

A goal of our collaboration was to develop interdisciplinary education initiatives for high school students using collections at The Walters Art Museum. During each lesson, students used their senses to make observations, collect data, and convey stories through creative expression. Linked below is our curriculum for others to use and adapt to their own educational settings:

- Observational Drawing Lesson: This lesson utilizes inquiry journals and drawing prompts to build observation skills while viewing museum objects.

- Interpretation Lesson: Participants learned more about Dr. Andrianavalona’s work through a video she created. We discussed the differences between descriptive and analytical questions while making observations of artwork in the museum. Students interpreted their perceptions based on the evidence observed through discussion, critique, drawing, and mixed media collage.

- Data and Discovery in Art Lesson: After observing the work of contemporary data artists like Nathalie Miebach, Laurie Frick, Jill Pelto, and Di Mainstone, students were prompted to collect their own data and create artwork displaying the results.

- Scientific Illustration and Inquiry Lesson: Students spent the fourth session at the Natural History Society of Maryland. While there, they conducted inquiry investigations through scientific drawings of plant and animal fossils. To learn more about this collaboration, visit our website, Exploring through Education.

Dr. Andrianavalona and I approached this project knowing we both had knowledge to give and gain. Yet, because this type of collaboration was new to us, it was at first difficult to imagine what would result from our unique partnership. National Geographic provided access to an online cohort of educator and explorer partners for support and knowledge-sharing but gave us license to experiment. As exciting as experimenting with new education programs can be, the constant risk-taking, creativity, and facilitation of a new curriculum can also be exhausting. It requires a lot of energy and time amidst a plethora of other responsibilities. It also demands failure and growth, which can be mentally taxing. However, embarking on this process through a collaborative relationship brings support and new expertise that invigorates the process. This produces perseverance, resilience, and a drive to continue learning. Her knowledge and experience introduced me to newfound interdisciplinary connections. As a paleontologist, she observes details like shape, texture, and color in ancient animal artifacts to learn about environments of the past. Her firsthand accounts have helped me develop guided-inquiry lessons of art objects that encourage students to learn about the interaction between historic human communities and natural environments.

Our partnership highlights the importance of educator and researcher collaborations for developing pedagogical approaches that engage young learners. Researchers have resources to enhance education curricula, while educators have pedagogical frameworks to engage young learners with that content. Dr. Andrianavalona’s accounts of her investigations helped me develop step-by-step inquiry simulations of this process for students to follow while observing museum objects. Learning what her observations revealed about the natural world gave students new insight on how to interpret their own observations. This resulted in increased access to knowledge.

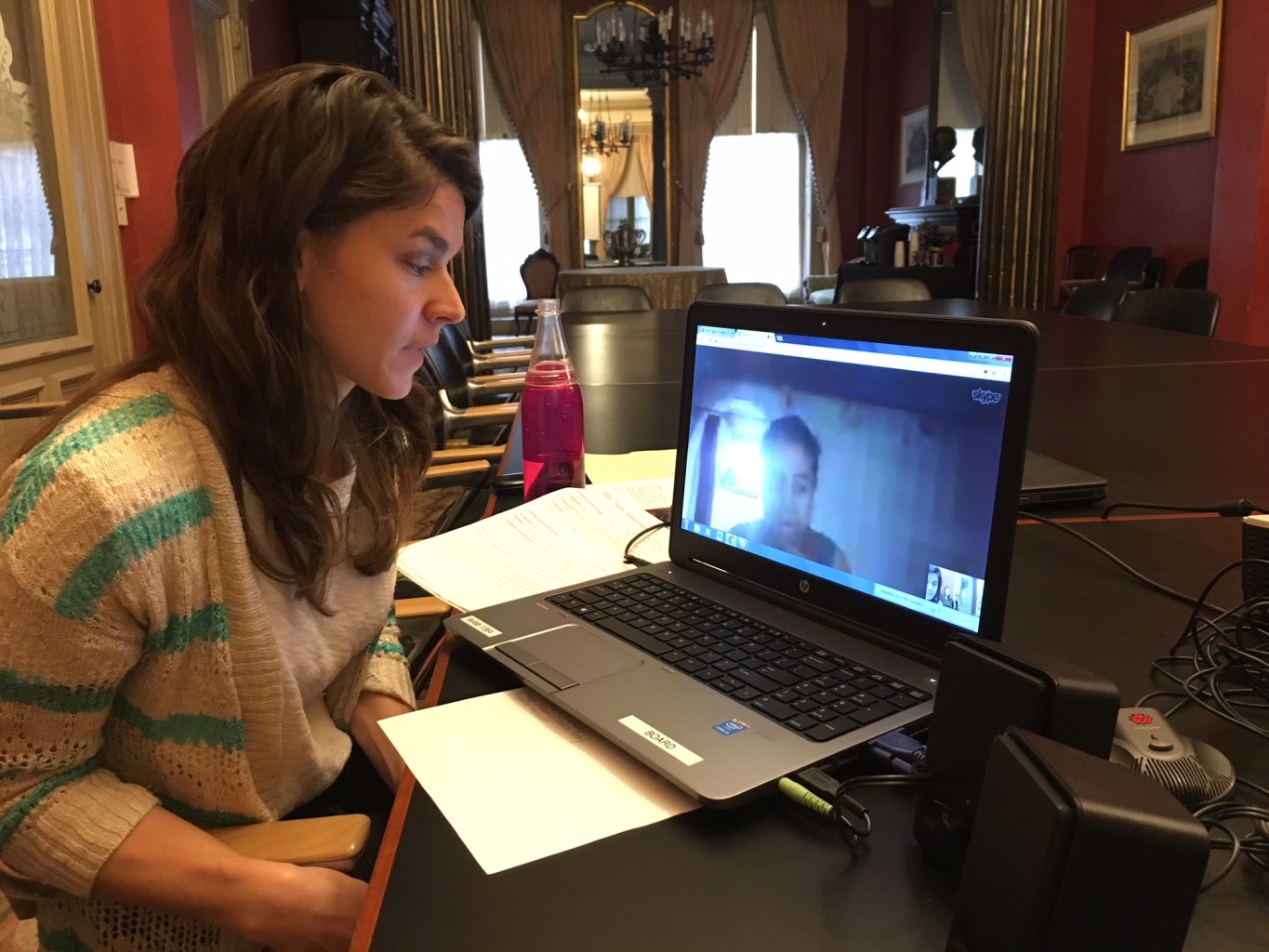

Our different backgrounds enabled us to create initiatives we could not on our own. In fact, it is because our interests and experiences are so different that we were able to create the interdisciplinary curriculum linked above. Our work continues! Dr. Andrianavalona invited me to assist with the pedagogical framework for an immersive science program for high school students in Madagascar titled “Sciencing Out”, which was funded by National Geographic and facilitated by Dr. Andrianavalona and ExplorerHome Madagascar Science Center, which she co-founded. I had the immense pleasure of joining the team in Madagascar to assist with implementing the program. As a part of the program, participating students worked alongside scientists in the field. They learned about science careers through inquiry investigation, participatory learning, and project-based learning methods. In collaboration with Boni Wozolek, Ph.D., and her students at The Crossroads School, Dr. Andrianavalona and I organized a video exchange between Baltimore City school students and “Sciencing Out” students in Madagascar. Each shared their STEAM-related environmental research and community action projects. While implementing the program in Madagascar, we also reflected on our collaborative process through a video interview.

Observing the Walters collection through Dr. Andrianavalona’s eyes reshaped my teaching practice, and helped me uncover new connections between art and science. International STEAM collaboration is exciting because the potential for learning, growth, and innovation is high. There were many moments in Madagascar where I found myself reflecting on how incredible this journey has been. It happened while learning about Malagasy language and culture, observing lemurs in the rainforest, learning the personal journeys of the ExplorerHome team, and watching students become empowered in their knowledge of STEAM topics. To enhance your own professional practice, and inspire the next generation of innovators, consider joining NatGeo’s network of certified educators. The network offers valuable support and training on the learning framework. It also creates access to leadership opportunities through programs developed specifically for educators. Such opportunities to cultivate partnerships within the global museum field will have a positive influence on the future of museum practice in research, exhibitions, and education. Platforms that connect educators and researchers, like the National Geographic Educator Certification, are essential for forming these needed alliances across fields. These partnerships can reveal new knowledge systems, which stretch and reinvigorate museum practice while enhancing visitor experiences.

About the author:

Susan Dorsey works as a museum educator at The Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, where she develops and facilitates classroom presentations, museum tours, and art workshops for students across the state. Susan received the 2019 Eastern Region Museum Education Art Educator Award, and the 2017 Maryland Art Museum Educator of the Year Award. She would like to thank Tsiory Andrianavalona, Ph.D., who contributed to all aspects of this project, as well as the National Geographic Society and the National Geographic Education team, especially Mary Adelaide Williamson. This work was conducted as part of graduate work through Project Dragonfly at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio.

About Dr. Andrianavalona:

Tsiory Andrianavalona is a paleontologist and a National Geographic Young Explorer from Madagascar. Her passion for ancient lifeforms and environments of the past led her to work on Madagascar’s fossil sharks from the Cenozoic, focusing on their identification, paleoecology, and paleoenvironment. After receiving her doctorate from the University of Antananarivo in 2016, she is now dedicating her efforts to inspiring interest and love for STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) fields among youth who are not only the next generation of scientists, but also Madagascar’s future change-makers and decision-makers. She is the co-founder of “ExplorerHome,” the first science center project in Madagascar, which aims to infuse curiosity and love for STEM fields among young Malagasy and help scientists to talk about their passion, all to create positive impact for her native country.