Around October, the weather gets cold, the days get shorter, and the spine begins to tingle. People start looking for eerie activities to scratch the itch, whether haunted houses, horror movies, or ghost tours. This is an interesting proposition for museums, who are custodians of much of the “haunted” history such activities involve, and always looking for ways to draw an eager public in. But how do you feed the appetite for unprovable ideas and lore without compromising on an educational mission?

Some museums have found a way through the dilemma, welcoming visitors for supernatural-themed programs to great success. We asked a few of those museums to explain what their programs are and how they’ve struck the balance.

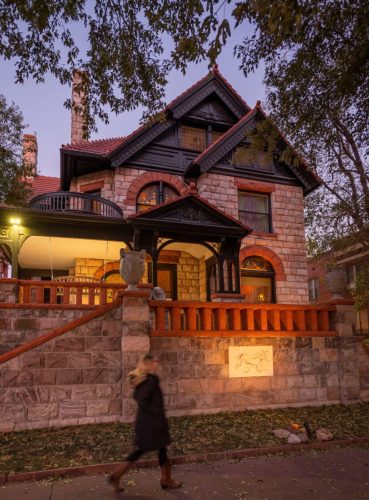

Molly Brown House Museum

Andrea Malcomb, Museum Director

Anyone from a historic house will recognize this scenario: a show on a certain channel wants to film at your museum. Sure, they feature crazy-haired “experts” who talk about aliens, you think to yourself, but there’s some real history too. Wait…they are paranormal investigators and want to film at your location? All night? Looking for…ghosts? Yes, ghosts. And, can they do it at no charge, they ask? And, by the way, they aren’t actually affiliated with said channel.

As a well-loved historic house, during the month of October, and indeed the whole year, Denver’s Molly Brown House Museum receives dozens of phone calls like the one above—even local news outlets get in on the haunted action during Halloween. So how do we balance this demand for all things haunted against our mission and our resources? We accomplish this by owning the message, conducting our own “ghost hunts,” and producing an annual sold-out haunted house-like event.

We start with the story of our house’s former owner, Margaret Tobin Brown, as a way to own the message. Special programs and tours interpret her life, her words, and the world around her as a way to explore notions of spiritualism and life after death. For instance, we share what Brown said in an interview after surviving the Titanic disaster, “I was born under a lucky star, I suppose. They told me a long time ago that I was born under ‘fire and water,’ that is to say, in July, and that I need have no fear of either of those elements.” This quote becomes a jumping-off point to talk about Late-Victorian mediums, and practices of phrenology, astrology, and other forms of divination.

Brown was swept up in spiritualism, calling on palm readers and hiring fortune tellers to entertain her guests here in Denver. On tours and during happy hour-style events, we highlight such history as the parlor games that were a favorite pastime at the turn of the last century, including “Raise the Table,” and spirit boards. In fact, spirit boards, or Ouija boards, have a unique connection to Denver—Helen Peters Nosworthy, a medium who lived down the street from Brown, was responsible for naming the popular spirit board “Ouija” in 1890.

The museum also conducts its own annual ghost hunting event titled Is Mrs. Brown Still Here? With Victorian Spiritualism as a starting point, we use the history of the house and its inhabitants to explore the possible “nighttime dwellers” of the 1889 home. On this interactive tour, guests hear the collected ghost stories from the house’s long history as well as some from around the neighborhood. Those stories are paired with house and family history as well as Spiritualism history to shed light on such tricks and tools as dowsing rods, table-tipping, Ouija boards, and ectoplasm. Women’s history is woven in through stories of such women as the famous Fox sisters, who made a career out of communicating with the dead. Our ghost-hunting guests, who get to try out dowsing rods and table-tipping while searching for spirits, see this as a rare chance to experience the home at night and happily pay a premium ticket price.

Lastly, each October the museum produces its biggest annual fundraising event, Victorian Horrors. Victorian Horrors is immersive environmental theater set within Molly Brown’s historic mansion in Denver’s Capitol Hill neighborhood. Rooms become stages for acclaimed local actors, who dramatically read passages from the rock stars of the Gothic horror genre. Such literature icons as Edgar Allan Poe, Mary Shelley, HG Wells, and Charlotte Perkins Gillman engage the audience with terrifying tales of unsettled ghosts, loves lost, and deaths revealed. As a women’s history site, we include stories written by lesser-known female writers such as Sarah Orne Jewett and Charlotte Riddell in each year’s line-up. The stories change each year to promote repeat attendance, and are collectively themed. For example, in past years this has meant stories all with a water or sea motif, stories set in Ireland, or stories set in old mansions.

Victorian Horrors performances sell out each year to over eighteen-hundred participants, with seventy-five mini-performances held for six to eight consecutive nights. The museum contracts with local actors at market rate, who are equally invested in the outcome of the event. They help choose the stories, and some have performed most or all of the twenty-six years of the event, and so consider this their favorite stage upon which to act. The actors also promote the event on TV and radio around the Denver community and are featured on the museum’s social media outlets. The expenses for this event, including actor salaries and marketing, are underwritten by enthusiastic annual local sponsors. For the museum, Victorian Horrors represents more than half of annual event revenue, generated in just about a week’s time of evening events.

Rather than sitting in a theater seat, the audience of literary nerds and connoisseurs of all things eerie “creep” from room to room in a non-traditional tour route, going through closets and other spooky spaces. Along the way they are regaled with scenes from such dramatic tales as “The Raven,” “Goblin Market,” and Frankenstein. The museum itself is adorned in period-appropriate Halloween décor, with the added spooky touch of such Victorian oddities and curiosities as taxidermy, specimen jars, and other creepy crawlies. Rather than hold these items in the collection, the museum partners with local oddities artists/dealers who create a Victorian cabinet of curiosities exhibit from ethically sourced specimens.

The museum sees repeat attendees every year, including many who have come all twenty-six years. Fans get excited when they read the story line-up and see their favorite actors in their favorite rooms. As part of our overall annual evaluation plan, we survey all attendees, and those who have come several times get a chance to vote for next year’s stories and win tickets to future performances. The community, as a result, sees Victorian Horrors as a signature Denver Halloween event that caters to adult audiences looking for an experience other than a scream-and-run type haunted house.

But, is the Molly Brown House Museum haunted, you ask? Our official response is, “just because we’re historic doesn’t mean we’re haunted,” but off the record? I think Edgar Allan Poe stops in from time to time to say, “Nevermore!”

Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library

Mark Nardone, Communications Manager

Last summer, Lori Blevins Myers, a supervisor of general services for the historic Winterthur estate, invited a medium into the temporarily vacant twin side of the house she lives in on the property. She had sensed presences in her home before, especially in the kitchen, “the happiest part of the house,” she says, so it seemed to her that ghosts should inhabit the other side of the structure, too.

In the living room, the medium detected an older woman happily listening to a young girl read a Bible. Then the medium and Blevins Myers proceeded upstairs, where they immediately smelled cigar smoke. When the medium looked, she saw a man dressed in a military uniform tapping his chest as if to say, “This house was mine.”

“It was absolutely Algernon,” Blevins Myers says. “She described him to a T.”

“Algernon” was Henry Algernon du Pont (1838-1926), a general in the U.S. Army during the American Civil War and a scion of the du Pont family, whose gunpowder manufacturing company made its members fabulously wealthy. Blevins Myers’ house was one of many he once owned. In his retirement from the military, du Pont greatly increased the land holdings he had inherited from an uncle, and fathered two children. Algernon’s son, Henry Francis du Pont, would go on to live his entire life on the property, amass the world’s most significant collection of early American decorative arts, expand his home, and convert it to a world-class museum.

At that museum—the Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library near Wilmington, Delaware—the encounter with the senior du Pont was just the latest of many for Blevins Myers and some of her colleagues. Last fall, for the first time, they enthusiastically shared some of their stories with select visitors during a special “Ghost Tales and Spirits” tour of the estate. During each of four sold-out thirty-minute tram tours on the Friday before Halloween, Blevins Myers and scheduling coordinator Jeni Jackson, who is also sensitive to supernatural presences, visited three sites on the thousand-acre property to recall their encounters at each. “It was PG-13,” Jackson says, “nothing too scary.” The evening also included a demonstration by a man who claimed to channel the spirit of Edgar Allan Poe, plus some creepy craft-making.

The event was an unqualified success. By the end of the tours, believers and skeptics alike were reluctant to break the spell. They lingered to discuss various experiences and ask questions. “It was like this great weirdo bonding,” Jackson says.

It was the kind of event Jackson had lobbied for since she began working at Winterthur eighteen years ago. Over that time, she estimates, she has had twenty experiences at various buildings on the estate, including former homes, unused barns, and inside the 175-room museum itself—the same museum visited by more than one hundred thousand people every year, some of whom might have had their own supernatural experiences. Even visiting scholars—people not usually associated with flights of paranormal imagination—have reported such encounters in the residences reserved for them. With these reports piling up, Myers and Jackson wondered, wouldn’t it be fun and interesting to share them with visitors?

For many years, the administration remained reluctant. Winterthur has an image and a reputation to protect. Not only does the museum house an important collection of ninety thousand objects; it is home to a historic garden, one of the world’s best art and object conservation graduate study programs, and a research library visited by museum professionals, students, and scholars from around the globe. Professionally and academically a leader in the field of American material culture—arguably the birthplace of the discipline—Winterthur certainly couldn’t afford to look silly.

Jackson laughs. “The idea was not well-received,” she says. “I’d get this eye roll, like, ‘Oh, she’s crazy.’” But despite their reservations, the brass did want to increase visitation, and were eventually persuaded a paranormal program could be a way to do that. When the museum’s retail manager pointed out the popularity of the annual holiday performances of A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens’ great-grandson Gerald Dickens—also a slight departure from Winterthur’s usual programming—“They went with it.”

There were other precedents for popular events that deviate from the museum’s mission but fit into the overall programming scheme. Winterthur’s largest single-day fundraiser, for example, is a steeplechase horse race that is attended by about twenty thousand people a year. The museum also hosts two highly successful family events annually: “Truck and Tractor Day,” a playful acknowledgement of Winterthur’s agrarian past, and “Enchanted Summer Day,” held in a beautiful children’s garden where the founder’s daughters once played outdoors, tying directly into the history of family life on the estate.

Winterthur continues to protect its reputation, but it also understands that the general public—the larger public that is not abidingly interested in decorative arts—is looking for something different. The beautiful estate has much to offer residents in the area beyond its connection to material culture studies.

Myers and Jackson’s event was such a success that, in the spirit of the season, the museum decided to repeat it—in slightly modified version—this year. And what better place could there be for such an event? Hundreds of workers have lived on the estate since its days as an experimental farm 150 years ago. Believers assume that some past residents, whether du Pont family members or employees, have the kind of attachment to the land that endures after death. And if some spirits attach themselves to objects, as Jackson asserts, then the untold number of people who once touched the ninety thousand pieces in the Winterthur collection have many stories to tell to those who wish to hear, to those who wish to have a bit of fun, and to those who might want to feel a mysterious tap on the shoulder.

Which should mean no end of “Ghost Tales and Spirits” tours in the future.

National Building Museum

Kristen Sheldon, Volunteer & Intern Manager

Ah, the great challenge of ghost tours in a historic and educational setting. When your museum is housed in a 132-year-old building there are bound to be some spooky tales, and ghost tours are a fun way to engage visitors, but how do you strike the right balance? The National Building Museum, an institution dedicated to sparking curiosity about the world we build, may not have as many ghost stories as its Washington, DC, neighbors the White House or the US Capitol, but the stories we do have are interesting and make for a fun experience. It’s helpful that these stories are anchored in real historic connections and objects, with a few “embellishments.”

One of my favorites of those stories involves shoes—really creepy shoes. When the building was renovated in the 1980s, the floors were repaired. Many of our rooms have empty spaces under the floor due to the domed ceilings below. During the renovation, workers found interesting objects in many of these pockets, including glass bottles, pieces of plaster decorations, and shoes. Lots of shoes.

Not pairs of shoes, not abandoned work boots, but a variety of solo men’s and women’s shoes from the late 1880s. Seeing these shoes in person is uncomfortable enough, but when you learn the reason for their placement in those corners it gets really chilling. Putting shoes beneath the floor of a building is an old European tradition to ward off evil spirits and bad luck. Why shoes? Because they are an item of clothing that maintains the shape of the wearer, and thus can be a stand-in for the actual person. This begs the question, why did our building, originally constructed as the Pension Building to serve Union veterans of the Civil War, have so many of these shoes buried in the floor, and does it matter that they have been removed?

We continue to look for ways to use the long, somewhat unconventional history of our building to create memorable experiences for visitors. A few years ago, we wove some of our ghost stories and the history of the building’s architect into a low-tech escape room experience. We tapped into historic documents and connections to the Civil War to create our puzzles. We also involved every variation on a padlock we could find. One puzzle, for example, involved Civil War-era ciphers, which would have been familiar to the veterans that used this building, but guests were given both a Confederate and a Union cipher, leaving them to decide which to use. The more details they learned and clues they found provided that answer and allowed them to move on.

2020 will see another to-be-determined iteration of a ghost tour experience. It’s still hazy and awaiting inspiration, but will tap into the success of the past and reflect the realities of staffing, space, and funding. It could be fun to have a haunted-house-style offering where people move around and are confronted by the spirits themselves, to heighten the fear factor, but we’ll have to see. In the end, it comes back to creating a fun experience that still shares our history and hopefully leaves people wanting more…if they survive.

About the authors:

Andrea Malcomb began working at the Molly Brown House Museum in 1999. Since becoming Director in 2009, she has pushed to expand the impact of this women’s history museum in the Denver community by expanding museum accessibility, updating public programs for evolving audience needs, and overseeing over $1 million in capital restoration and improvements.

Mark Nardone is the Communications Manager at Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library. Prior to joining Winterthur last year, he was the longtime award-winning editor at Delaware Today magazine. He vaguely hopes to someday have a paranormal experience.

Kristen Sheldon has been the Volunteer & Intern Manager at the National Building Museum for eight years. Her tasks include recruiting, training, scheduling, and creating ongoing learning for volunteers; creating tours and programs for visitors; and mentoring interns. Other duties include throwing amazing volunteer parties and acting as keeper of ghostly tales and historic building knowledge. Her prior experience includes work at the U.S. Capitol, The National Museum of the American Indian, and a variety of other institutions both large and small. Kristen wishes she could have had about eight different majors in college and grad school, but could only manage English, Studio Art, and Museum Education. She uses her work as a museum educator to fill her mind with knowledge. Current pursuit: all things clouds.

Skip over related stories to continue reading article

Comments