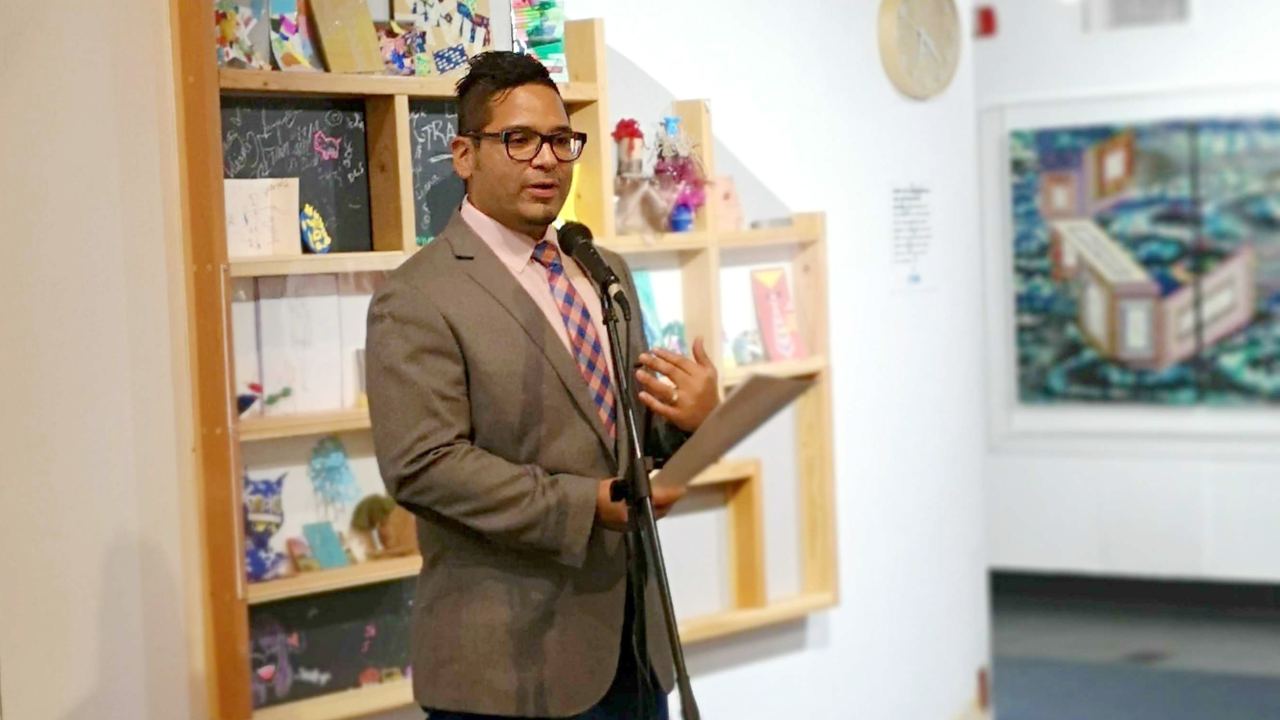

According to his nominator, David Rios, Director of Public Programs and Curator of Contemporary Art at the Children’s Museum of Manhattan (CMOM), “excels in building experiences and shaping content in ways that create engagement and dialogue between parent and child.” Through the programs he creates and the exhibitions he curates, David has created an environment that is welcoming, inclusive, and accessible to children and their families. Learn more about David’s unconventional path to museum education and how that has shaped his values and commitment to creating equity for diverse audiences.

—Veronica Alvarez, EdCom Leadership Awards Chair

Dear Museum Hiring Committee,

When considering a new hire, what do you look for? What takes priority? How does this inform your job descriptions? How does it inform how you review a resume? And, ultimately, how does it inform your hiring decisions?

How do you define expertise? For instance, for an entry-level position, how would you weigh Applicant A, who completed a graduate program straight through with an impressive GPA, against Applicant B, who, while completing their bachelor’s degree, earned an average GPA, but held jobs and internships garnering valuable and transferable experience? Your response might be, “well, it depends.” And that may be true, but dear hiring committee, I write to you today to advocate, just for a moment, that we consider Applicant B.

As I look across the museum landscape and see a predominantly white cohort of individuals and board members running our cultural institutions, I believe it comes down to this very distinction: Applicant A versus Applicant B. Of course there are other factors. But for brevity, and to meet the goal of learning about the 2019 American Alliance of Museums’ (AAM) Education Professional Network (EdCom) Award for Excellence in Practice winner, let’s focus on the story of Applicant B.

EdCom states that nominees of the Award for Excellence in Practice are “knowledgeable, demonstrate creativity, and succeed in stretching the boundaries defining the parameters of good practice.” But if I in fact do meet these standards as the 2019 awardee, it is not because of an academic program, or the act of thesis writing, or because I took a straight path to where I am now. In fact, through this article I hope not just to shed light on my supposedly uncommon career path, but to inspire a realization that there is not, nor should there be, one common path to a career in museums and museum education.

When I am asked to talk about my museum career path, I never know where to start. After presenting on conference panels or giving talks, I’m often approached by aspiring museum professionals asking for advice. How did I get here, and through what graduate program? Should they even go to graduate school? When this happens, I always feel like I’ve been caught in some farce, that “the jig is up.”

I didn’t study museum education. I didn’t attend a museum studies program. I didn’t get a master’s degree. I stand uneasy in front of these eager individuals. Sweat building, I often say, “I’m not the right person to answer that question.” But after I see the disappointment in their eyes, I leave them with, “stay open to possibility and opportunity.” Generic, I know, but it’s this very sentiment that informed some of my biggest decisions.

I never intended to be in museum work. It wasn’t something I dreamed of doing, or even knew was a possibility for me. In fact, if you were to predict where I’d end up when I was younger—a mixed-race, asthmatic, first-generation Puerto Rican kid from New York wrestling with reading and writing, and struggling with obesity and a growing awareness of his homosexuality—you’d be hard-pressed to imagine me in a leadership role at a museum.

But fast forward a few years, and with the help of those very limitations and struggles, I would develop a unique perspective. I’d acquire new skills and talents and meet people who would shape my path. Ultimately, I would go on to lead multiple careers in the arts: today I am a visual artist with an active studio practice and upcoming 2020 exhibitions, a museum professional overseeing the second iteration of a major exhibition, and an independent curator developing shows for 2021-2022.

This kid with reading and writing delays would go on to write and win grants from the Doris Duke Foundation, the Institute for Museum and Library Services, the National Association of Latino Arts and Culture, and the Ford Foundation. He would work on national media projects, touring exhibitions, and experimental program spaces.

But to get to all of this, I started in a very different place.

I attended school for visual arts at The Cooper Union in New York City. Tuition was covered but there were still significant financial requirements for attending, which meant taking out loans and taking on jobs while in school. Since I was the first in my family to pursue the arts in higher education, I looked for jobs that would teach me ways to finance a career in the field, which I was determined to do. I worked part-time at Wave Hill as a gallery attendant, at the Children’s Museum of Manhattan as an educator, at The Cooper Union Saturday Program as an administrative assistant, and at The Cooper Union Outreach Program as a teacher’s assistant (TA) and recruitment associate. Both of these latter programs, which I had the privilege of attending in high school, actively serve young people of color, preparing them and making them more competitive to enter the visual arts world. My experience in them, both as a student and later as an employee, inspired me to consider youth development work as a career path.

This led me to my first full-time job with the Children’s Museum of Manhattan as their Manager of Community Outreach and Internships. There I ran internships for high school, college, and graduate school students—leading professional development in program design, inquiry-based learning, and teaching through the arts. I also co-developed and facilitated professional development workshops for nurse practitioners, librarians, and teachers. Through all this, the most vital work was with youth, particularly in supporting and mentoring young people of color in the arts, museums, education, or wherever their lives led them. My own professional development was supported by the Career Internship Network (CIN) and a fellowship in the Youth Development Leadership Program of the Youth Development Institute, part of the Fund for the City of New York. This led me to explore more youth-development-focused positions in the field, and to ultimately leave the Children’s Museum to explore more art and design-specific institutions with a youth focus.

I was offered a position at the Smithsonian Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum as their Manager of Youth Programs. In this role, I developed design-based experiences and professional development opportunities for New York City teens, which included taking them to visit design studios and introducing them to professionals in fashion, digital media, and architecture. I’d then invite these same designers to lead workshops at the museum and place our participants as high school interns at their studios. I also oversaw the museum’s annual Teen Design Fairs in Washington, DC, and New York City. It was at the Cooper-Hewitt where I began to stress the need to partner with designers and arts professionals who reflected the diversity of my students and audiences. I made a commitment to showcasing a wide breadth of Black, Latino, and Asian designers.

I continued these efforts when I rejoined the Children’s Museum of Manhattan in my current role, as the Director of Public Programs and Curator of Contemporary Art. My team and I develop programming that provides children with a sense of the possible—a chance to see themselves in our guest artists, presenters, and performers, as well as in the content of our workshops and programs. Like in my work at the Cooper-Hewitt, I make a concerted effort to feature artists, designers, chefs, and all kinds of creatives who reflect our audiences’ demographics, and who run the gamut from emerging to established. In the programs I develop it is critical to me to feature content, art forms, and narratives that represent and explore underrepresented voices. Ultimately, my goal is to make room for different stories—ones that differ from the typical narratives we hear. These different stories must rise to the surface if we are going to see our communities reflected in museums and cultural institutions.

But as I began my letter to you, dear hiring committee, this isn’t just about holding a platform for showcasing diversity. Institutions must be driven and guided by diverse voices in administration and leadership as well. Fortunately, many museums are making an effort to address the impact of structural racism, but it is more entrenched than people realize. I’m reminded of Lonnie G. Bunch III, the newly appointed 14th Secretary of the Smithsonian, and his article “Flies in the Buttermilk: Museums, Diversity, and the Will to Change” where he recounts being mistaken for an elevator operator by a white visitor who upon realizing her error exclaimed “I just assumed….” Black, Latino, and other people of color in this field still face unconscious bias, tokenism, and blatant racism. So, in addition to reevaluating recruitment and hiring practices as Bunch lays out for us, our future museum professionals of color need the support of their mentors, peers, colleges, and universities to best prepare them to overcome these external barriers, as well as internal ones.

If it weren’t for the people I met along the way, who not only challenged me but put their trust in me, I might not have the career I have today. These individuals made educated decisions, perhaps took risks, and quantified the value of what I brought to the table. Whether I was applying for a job, a promotion, or a professional program, they weren’t distracted by my lack of a master’s degrees, or by my GPAs and (sometimes unrelated) areas of study. They were only ever concerned with my experience, my drive, and my ability to keep learning.

In her TED talk, “Why the best hire might not have the perfect resume,” human resources expert Regina Hartley shares that “getting into and graduating from an elite university takes a lot of hard work and sacrifice. But if your whole life has been engineered toward success, how will you handle the tough times?” Working toward a degree takes hard work and commitment, which should not be overlooked or underrated. However, I ask you to consider those who put in the same hard work into their education but with added purpose, possibly while balancing multiple part-time jobs, helping run a family business, or raising a child.

If the professionals, institutions, and programs who offered me opportunities had relied on limited and cliched parameters, like my education, they would have missed out. So dear museum hiring committee, your colleagues, and your boards: if you want innovation, evolution, and a sustainable future for your institutions, don’t miss out. Take the time to learn Applicant B’s story.

At this year’s AAM conference where I received EdCom’s Award for Excellence in Practice, I was elated to hear about the launch of Facing Change, AAM’s national museum board diversity and inclusion initiative. However, I was disappointed to hear these efforts introduced alongside statements like “we need to be patient and take our time.” On a practical level, I understand the need for a steady, deliberate approach to transforming museum cultures, but it’s 2019. These issues have been with us for years. Bunch asks, “What is it that makes progress in this area so incremental and so glacial?” Further, he shares his anxiety on the continued challenges, assumptions, and resistance around this issue, “[I’m] worried because after more than 20 years in this field, I am still hearing some of the same debates and conversations.”

And while we are seeing some improvements, as noted in recent reports from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and Americans for the Arts, there is still a long way to go. As Madeleine Grynsztejn, director of the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago and the current president of the Association of Art Museum Directors, noted in an interview in Artsy, “There’s a lot of work still to be done . . . there’s been very little change with regards to race and ethnicity in the highest museum leadership positions in the most fiscally large museums.”

Museum hiring practices can and must be adjusted today. I urge you, dear museum hiring committee, to take the time to get to know the whole story. The Applicant Bs of the world provide a different, more nuanced story. Seek them out, and abstain from the stories you always accept, the stories we keep hearing, and that are constant influences on our museums and cultural institutions. Seize the opportunity to present perspectives, cultures, and narratives we haven’t heard. It’s 2019. We are all tired of the same old story.

Agree; my first career was in the banking industry where I received invaluable management, financial, marketing training – all of which served me well as an Executive Director in an contemporary art museums. I might add I was a rare breed as a Mexican-American in that industry and my first AAM conference was quite an (insulting) shock. The bottom line is Running a museum is not brain surgery; it’s basic management/fundraising, media and political skills – with a clear vision. I’m also concerned about the gender balance in these spaces.