As an avid reader of Chicanx/Latinx literature, I’ve been closely following the national conversation about the recently released novel American Dirt by author Jeanine Cummins. The conversation—which highlights issues of race, ethnicity, and identity; how stories are told; who should tell those stories; and the responsibility of the publishing industry in these decisions—holds several valuable lessons for those of us in the museum world.

In case you’re not familiar with the story, American Dirt is about a mother and her son who flee from Mexico to the United States after the rest of their family is killed by a drug cartel in their hometown of Acapulco. The book gained national attention when its publishing company, Flatiron Books, promoted it as a “Grapes of Wrath of our times” and Oprah Winfrey selected it for her popular Oprah’s Book Club. The response to the book and author Cummins, who as recently as four years ago publicly identified as white before disclosing that she had a Puerto Rican grandmother prior to the book release, was swift.

Critics note the book relies on harmful stereotypes and caricatures Mexican culture. The response has even triggered a Twitter hashtag, #writingmylatinonovel, which social media users have used to reject the perpetuation of harmful tropes about Latinx culture. Magnifying these issues is the fact that Cummins reportedly received a seven-figure advance payment to write the book, an unheard-of sum for the Mexican and Latinx authors who have been writing authentic stories about border and borderlands issues for years. In addition to criticisms about the book itself, several notable Latinx writers including Myriam Gurba launched a campaign, #DignidadLiteraria, to promote Latinx authors and begin a dialogue about inequitable practices in the publishing industry.

As this discussion continues, it provides an important opportunity for museum professionals to critically examine the parallel issues which exist in our own field, and how we navigate issues of inclusion and representation in order to lead museums towards increased accessibility, relevance, and sustainability.

Representation in Leadership

The #DignidadLiteraria movement places a spotlight on the inequalities existing in the publishing industry. According to a 2015 report by Lee & Low, 79 percent of the publishing workforce is white/Caucasian. The percentage is even higher—86 percent—at the executive level. Only 2 percent of publishing executive positions are held by Latinx professionals, and 2 percent are held by African Americans. In the museum field, the data is similar. The 2018 Art Museum Demographic Survey published by the Mellon Foundation found that 3 percent of people in art museum leadership positions are Latinx and 4 percent are African American. In addition, the 2017 Museum Board Leadership report, published by AAM in partnership with BoardSource, found that nearly half (46 percent) of museum boards were all-white. This data, and the recognition that museum leadership must evolve in order to reflect the increasing diversity of communities across the country, has informed and inspired the AAM Facing Change Report and the subsequent Facing Change initiative currently underway.

The dialogue around American Dirt reminds us that representation is critical at the decision-making levels of institutions and industries in order to enact meaningful and lasting change. As a result of meetings with representatives from #DignidadLiteraria, Flatiron Books and parent company Macmillan Publishers have agreed to expand Latinx representation in their staff and publications, promising to draft an action plan to present to the group. While this is a promising start, their success hinges on how this new plan is implemented and whether they can foster an environment in which their new Latinx employees are able to thrive.

Without a critical mass of employees from diverse ethnic and cultural backgrounds at all levels, and an equitable and inclusive organizational culture, underrepresented employees can face a lonely, uphill journey in any industry. I have seen this in my own work experience. Prior to joining the museum field, I spent over twenty years in higher education, nearly all of them working at universities considered Hispanic Serving Institutions (HSIs). Despite the designation, Latinos and Latinas remain significantly underrepresented on the faculty and staff at many HSIs. During my time in higher ed, I witnessed firsthand how colleges and universities would hire Latinx faculty and administrators only to set them up for burnout, or worse—failure. It wasn’t uncommon for new Latinx hires to be assigned to an unrealistic number of committees as the “diversity representative,” or absorb additional duties such as advising the student Latinx organization or translating marketing materials without recognition or compensation. While hiring a more diverse staff is an important step, it’s equally critical that institutions develop a more inclusive organizational culture where they can succeed.

Elevating Community Voices

The other issue at the forefront of the American Dirt dialogue is about which stories are told and whose voices should be amplified. Museums, like publishers, have a tremendous opportunity to reflect and elevate, in our galleries and through our public programs, the stories and viewpoints of our increasingly diverse communities. In the dialogue about American Dirt, the question isn’t whether issues along the United States-Mexico border are worthy of discourse, but about the way in which these narratives are shared and how we create space to amplify Latinx voices. If American Dirt was an exhibit, how could we justify not including the viewpoints of those individuals most impacted? In her article “Anti-Racist Curatorial Work,” Elena Gonzales highlights collaboration as an effective curatorial practice for inclusion, explaining that “this practice of collaboration, which is a thread through anti-racist work, makes sense because it defies the practice of othering that is at the root of racism. When we share histories and develop shared senses of identity, when we collaborate respectfully on understanding our past and envisioning a shared future, racism has no purchase.”

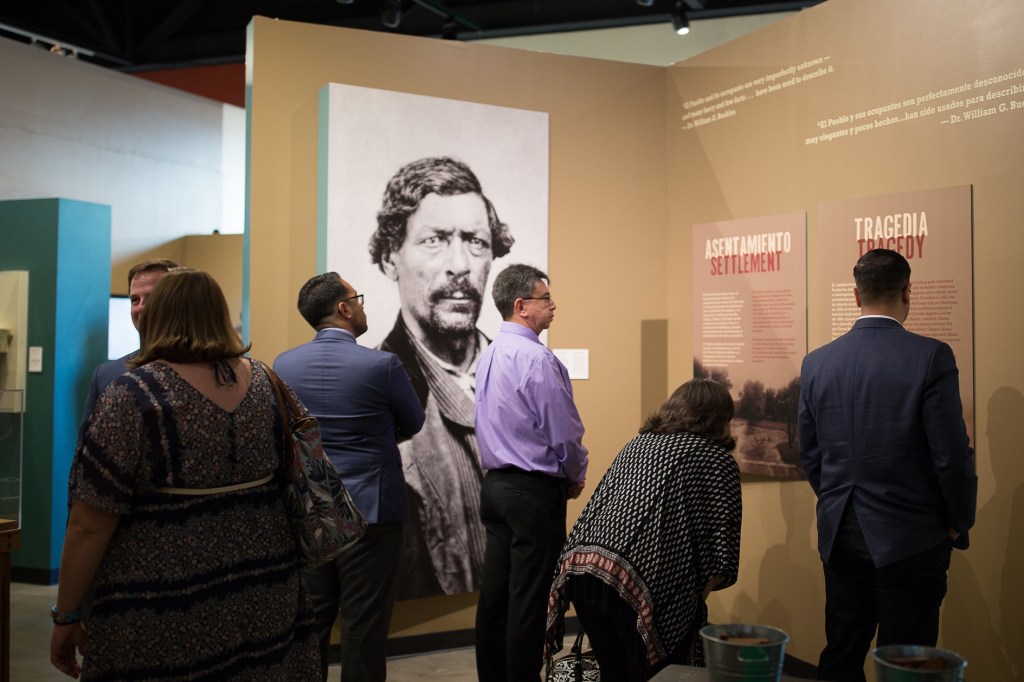

Thoughtful, authentic community engagement and collaboration are key elements of an initiative underway at History Colorado Community Museums, Borderlands of Southern Colorado. The project takes place at our three southern Colorado museums (El Pueblo History Museum, Fort Garland Museum and Cultural Center, and Trinidad History Museum), located in communities that are approximately 50 percent Latinx, with many residents able to trace their ancestry to the early mixed Hispano-Indigenous families who lived in the region prior to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo of 1848. The Borderlands project, inspired by the work of Chicana feminist scholar Gloria Anzaldua, explores the region’s history and culture through the intersection of cultures, ethnicities, landscapes, religions, and identities; and centers community voices that have long been excluded. This has been accomplished through a variety of strategies, including ongoing dialogue with a broad range of residents and community partners, the development of an advisory committee empowered to provide local knowledge and real feedback, and utilization of community oral histories and stories. As a result, community response to Borderlands exhibits, lectures, and other programming has been tremendous.

On May 1, 2018, El Pueblo History Museum celebrated the opening of our first Borderlands exhibit with over thirteen hundred community members in attendance—the largest exhibit opening ever at a History Colorado museum. The exhibit led to partnerships with the Colorado Coalition for the Educational Advancement of Latinos (CoCEAL), the Genealogical Society of Hispanic American (GSHA), the University of Denver’s Latino Leadership Institute, and others. The opening, along with subsequent related programming, elicited a powerful response from participants—many of whom noted that this was the first time they had seen their personal story represented inside a museum gallery. According to Dawn DiPrince, History Colorado Chief Operating Officer and lead developer of the Borderlands initiative, “There’s something really powerful about seeing yourself included in the collective narrative, and something equally destructive when you don’t. When we’re able to reclaim histories that have been erased, it strengthens communities.”

There is no doubt the conversation around American Dirt provides us, as museum professionals, with a significant learning opportunity for navigating the critical issues of representation and inclusion. By taking meaningful action to diversify our institutions and creating opportunities for elevating community voices, we can take important steps toward developing more welcoming and inclusive spaces for a rapidly changing society.

About the author:

Eric Carpio is a Facing Change Senior Diversity Fellow. He is the Deputy Community Museum Officer for History Colorado and the Director of the Fort Garland Museum & Cultural Center. He currently serves on the board of directors for the San Luis Valley Immigrant Resource Center. He has a B.S. in Business Administration from Colorado State University and an M.A. in Counseling and post-graduate leadership certificate in Higher Education Administration & Leadership from Adams State University.

Skip over related stories to continue reading article

Thanks for the article, Eric. Reading the book now but didn’t want to buy it so Charlene Garcia Simms lent it to me.