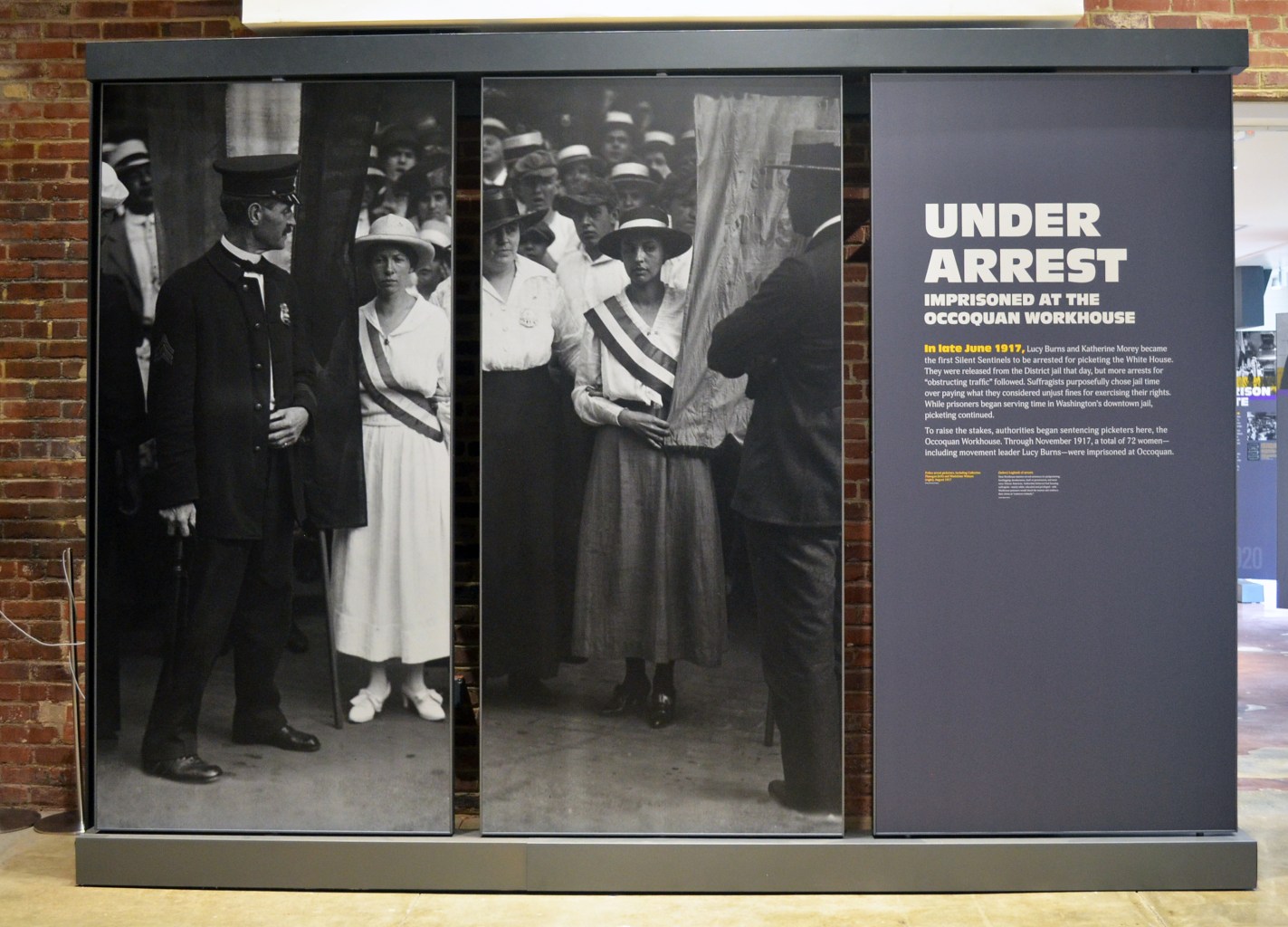

Suffragists are recorded as the first in US history to use silence as protest, calling themselves “Silent Sentinels.” US suffragists (rather than British suffragettes) were also the first to picket the White House. They stood in front of Woodrow Wilson’s office rain or shine, day or night, six days a week, from January through November 1917.

Their request seemed simple, that: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.” But the women were met with Wilson’s declaration that he was “definitely and irreconcilably opposed to woman’s suffrage,” that “the type of woman who took an active part in the suffrage agitation was totally abhorrent.” The Silent Sentinels carried large banners with statements like America is not a free democracy if women cannot vote, and, once imprisoned, “To ask freedom for women is not a crime.” Protesting suffragists were fraudulently charged and sentenced with obstructing free passage of the sidewalk and unlawful assemblage. They were transported about twenty miles south of Washington, DC, to the Occoquan Workhouse in Lorton, Virginia, where they were sentenced to terms of up to seven months.

Prison conditions were unsanitary, and the food was worm-infested and too meager to sustain the women through forced labor, which included sewing male prison uniforms although many women claimed they didn’t know how. Infectious skin diseases were rampant and left untreated by the prison hospital. The suffragists were denied mail and contact with family and attorneys. When the women were placed in solitary confinement, they were given buckets as toilets. But Nevada activist and the National Woman’s Party first chair Anne Henrietta Martin promised, “As long as women have to go to jail for petty offenses to secure freedom for the women of America, then we will continue to go to jail.”

Women from all social strata risked their health and reputations to protest, and it’s estimated that two thousand took a turn on the picket line. The oldest woman arrested in front of the White House was seventy-three, and one of the youngest was twenty-year-old Dorothy Day, who later co-founded the Catholic Worker Movement. The woman who was group leader during her three Lorton prison terms was Brooklyn-born Lucy Burns, and a museum bearing her name opened on January 25, 2020, at the former site of the prison. The Lucy Burns Museum gala opening celebration is slated for May 9, during the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment to the US Constitution that legalized a woman’s right to vote. Through the stories of Lucy Burns and her compatriots, the museum will tell the history of the movement toward franchise.

The DC government created the Occoquan Workhouse in 1910 as a Progressive Era project to reimagine incarceration, without watchtowers or cells, only dormitories. Inmates built the Colonial-Revival-style buildings using bricks made at the kilns on the banks of the Occoquan River. The complex was almost self-sustaining, and prisoners grew fruits and vegetables, raised livestock, and ran a slaughterhouse. An onsite dairy operation provided milk for schools and a hospital in the District as well as for the prisoners.

When the prison closed in 2001 as the DC Correctional Facility at Lorton, the entire complex was slated to be leveled, along with all evidence of imprisoned lives. Lifelong Lorton resident and twenty-six-year prison employee Irma Clifton was instrumental in saving the buildings, vital records, and artifacts. She helped convince Fairfax County to purchase the site for $4.2 million in 2004, and secured the Workhouse on the National Register of Historic Places soon after, an act that saved all structures built before 1971, including three dozen buildings constructed between 1921 and 1940.

Clifton had studied historic preservation and adaptive reuse at Mary Washington College, before coming to Lorton to work in management and security. During her tenure at the prison, she assembled and maintained a collection of documents and items as the informal Department of Corrections historian, chronicling the reformatory’s consequential history. She saved items made at the prison—including farming implements, manhole covers, fire hydrants, and license plates—along with agricultural production documents, correspondence, many photographs, and the 1910-1925 prison escape log. In a shrewd move, she plucked the 1916-1919 DC jail logs from the trash as the prison closed, which include the names, offenses, and sentences of all suffragists arrested during the 1917 and 1918 protest periods—the only documents where that information was recorded.

In 2008, Clifton shepherded some of the site’s buildings into an adaptive reuse as a creative complex, the nonprofit Workhouse Arts Center, situated on fifty-five acres of the former prison. Former dormitory spaces were repurposed into studios for about eighty regional artists, and an auditorium for theater performances, classes, and lectures. The prison’s quad became an events space, featuring annual fireworks displays, summer concerts, Halloween events and Brewfest, plus special event rentals. Clifton also wanted to share the stories of the Silent Sentinels and their mistreatment, notably on “The Night of Terror,” and reserved an eleven-thousand-square-foot dormitory to become a suffragist and prison history museum.

Developer and philanthropist Richard Hausler donated over $3 million to the Workhouse Arts Center to complete the Lucy Burns Museum renovations in 2019. The museum’s exhibits explore ninety-one years of prison history and are designed by Tracy Revis of Howard+Revis and installed by Capitol Museum Services. Featured are larger-than-life-sized sculptures by Studio Eis of suffragist leaders Burns, Alice Paul, and National Woman’s Party co-founder Dora Lewis.

The museum was named after Lucy Burns, rather than the better-known Alice Paul, because Burns was actually incarcerated at Lorton and Paul was not. Burns and Paul were comrades-in-arms who co-founded the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage, which eventually became the National Women’s Party. The well-educated, well-traveled pair had met as young activists working for Emmeline Pankhurst in the United Kingdom and around Europe. They imported more hardline British tactics when they returned to America to ramp up national suffrage actions. In addition to the White House protests, they purposely sought getting arrested—and being called political prisoners—as well as going on hunger strikes, to garner media and public attention. Their methods to track representatives’ positions and hold them accountable continue to be employed by grassroots activists today.

Alongside the suffragists, the museum highlights other notable former prisoners. For example, Chuck Brown, DC’s “Godfather of Go-Go Music,” learned to read and play music during his eight-year sentence at Lorton in the 1950s. (He had traded two cartons of cigarettes for a guitar.) Noam Chomsky, the “Father of Modern Linguistics,” was jailed there for anti-Vietnam War activism in the 60s, and Norman Mailer, who wrote his Pulitzer Prize-winning The Armies of the Night based on the October 1967 Washington peace demonstrations, was fined and jailed there for civil disobedience. Some of the people arrested during 1968’s Poor People’s March of Washington spent a few days inside. Prominent musicians including Ella Fitzgerald, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and Frank Sinatra performed for the prisoners on the ball field in the 50s and 60s.

Historical objects on display include prison-made tools for farming and industry, wall murals and graffiti, religious items—including a twelve-foot, six-hundred-pound plaster crucifix with the likeness of a death row inmate as Jesus—and a large collection of shivs, shanks, and restraints.

The Lucy Burns Museum also highlights the African American fight for suffrage, a key component of social justice goals including equal jobs, education and healthcare. Black men had been granted the right to vote in 1870, and ostensibly Black women gained voting rights alongside white women. But Jim Crow laws, violence, as well as gerrymandering and voter suppression, kept (and, in some cases, still keep) African American voters away from the polls. Black suffragists were largely ignored or barred from participating in the mainstream movement by white women, so they worked through organizations like the National Association of Colored Women instead.

In a display called “The Vote That Wasn’t Theirs,” the museum shares the stories of Black suffragist leaders like Dr. Anna Julia Cooper, a PhD in math; Mary Church Terrell, noted educator and NACW founder; Nannie Helen Burroughs, editor and founder of the National Trade and Professional School for Women and Girls; and Ida B. Wells Barnett, who was born into slavery and became a teacher and journalist. Wells Barnett ran an anti-lynching campaign and was co-founder the NAACP. A notable suffragist herself, she marched down Pennsylvania Avenue with the Illinois delegation in a parade of more than eight thousand women in 1913.

Ida B. Wells died in 1931 and Lucy Burns died in 1966. Irma Clifton succumbed to pancreatic cancer on August 30, 2019. None lived to see the museum opened. But they and the suffragists are silent no more: their stories are being told into the new century.

About the author:

Karin McKie is a writer, educator, and activist. Her cultural anthropologist mom Laura Lou McKie worked at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History for twenty-three years, retiring as Director of Education in 2002. In her “retirement,” Laura has been an almost full-time volunteer as the Lucy Burns Museum’s director, serving as curator, project and collections manager since 2009. The Women’s History Month committee of the Fairfax County Commission for Women selected Laura to be honored with a special proclamation by the Board of Supervisors on March 10, 2020, saying “We are honoring you for your years of devoted work on the suffrage museum and making the Lucy Burns Museum a reality. We cannot think of a worthier person to honor during the 100th anniversary of the 19th amendment.” Laura adds, “And if it wasn’t for Irma, we would not have this museum today,” and dedicates her work to Irma, Lucy, and the suffragists. Mother and daughter McKie also want you to vote.