You wouldn’t be wrong to call these times chaotic. But chaos, though not always life-threatening in the way of COVID-19, is not uncommon in our work.

In November of 2011, I was a CEO leading the opening of a brand-new science center—new facility, new location, new mission; new store, new café, new staff, and new exhibits. Years of planning, visitor experience development, construction, and training all ready to come together on opening day, ready for our expectant visitors to arrive. And arrive they did, by the thousands. School groups flocked in, thirty students at a time, as did moms and dads with toddlers eager to visit the new children’s museum gallery. And even with all the planning and preparation, it was still chaotic. “Where are the washrooms?” “I‘ve lost my child!” “Where is the bed of nails exhibit?” My team was shell-shocked. As their leader I was responding to critically important but rather basic operational questions, while also trying to keep my eye on our overall strategies to sort through short-term challenges versus long-term issues.

Though we were ultimately successful in settling ourselves and our audiences into patterns that were more rational and comfortable, it wasn’t until I came across the writing of David Snowden and others who work in complexity theory that I found a framework to help me respond and make decisions in busier times. I want to share that framework now, as we all make sense of the chaos of this pandemic and prepare our museums to eventually reopen.

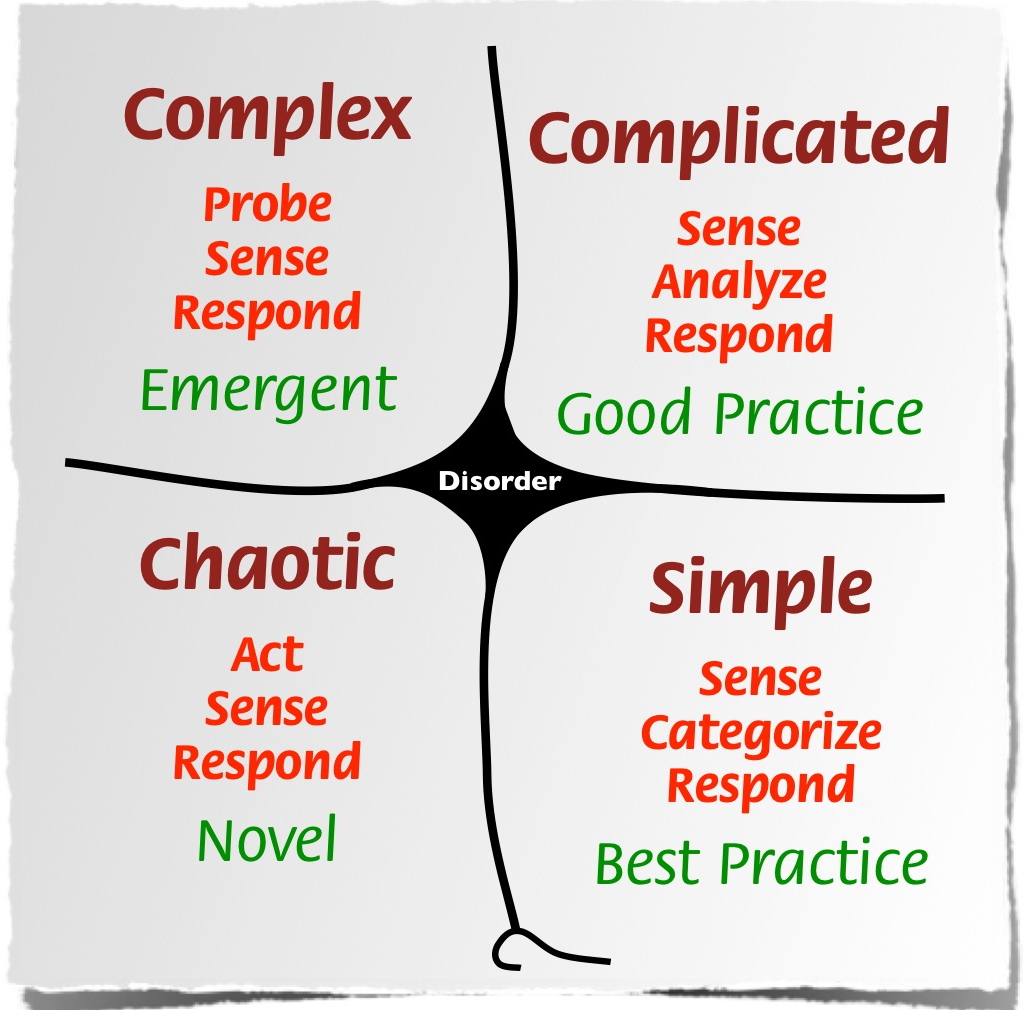

Snowden calls this framework “Cynefin” (pronounced ku-nev-in), after a Welsh word that “signifies the multiple factors in our environment and our experience that influence us in ways we can never understand.” He and co-author Mary E. Boone write that “leaders who understand that the world is often irrational and unpredictable will find the Cynefin framework particularly useful.” The framework lays out four different domains to describe the circumstances in which we make decisions. As a leader, identifying which domain you are in can help you act in contextually appropriate ways. It can help you make decisions when your preferred leadership style is in opposition to the situation you are facing. It can help you determine whether it’s a time to let solutions emerge in new and exciting ways, or to follow best practices well grounded in experience. Here are the four domains:

Simple/Obvious Contexts

In “simple” or “obvious” contexts, the correct decision is often clear to most of the team and is repeatable, like a recipe. When the situation is well analyzed and the management decision is straightforward, then easy delegation and information-sharing is typically sufficient. For example, a change of operating hours at the museum requires basic communication and schedule changes. The decision may have resulted from assessing requests from your members to open the children’s gallery thirty minutes earlier to balance nap-time for their toddlers.

In the simple domain, leaders “sense, categorize, and respond.” The follow-through is an extension of already established processes—ensuring admission staff are onsite and ready to scan memberships, that cleaning staff have finished daily preparations, etc.

While this form of decision-making would appear to be straightforward, the Cynefin framework places it adjacent to “chaotic,” and for good reason. How many times have we experienced a basic change of operations that triggers a series of unintended consequences, possibly because we were complacent and oversimplified the dynamics at play? Remember that “best practices” are based on the past and can indicate the average result, not the target you need to aim for.

Complicated Contexts

In the “complicated” domain, there are likely multiple answers to the situation you face, and the relationship between cause and effect may not be clear to everyone. Here, as a leader, you need to “sense, analyze, and respond.” For example, sensing that school group attendance is dropping may be straightforward from the revenue and attendance reports, but analyzing the cause of it is not. Is it related to school budgets, new competition in the education market, or are your programs getting stale?

In the complicated context, you need experience (for example, your lead in the school market) but also the perspective of non-experts, who may see opportunities that ingrained thinking could miss. This can cause challenges around the management table, but your leadership in these moments is critical to the health of your organization. You must listen to your experts while making room to entertain alternative perspectives.

Complicated decisions can take time, but there is always a trade-off between simply making a decision and working with the immediate results versus waiting to find the right answer and delaying response. However, if the right answer continues to elude you—if you can’t find a decision to address the drop in school group attendance, for instance—then the situation may be complex, not complicated.

Complex Contexts

In the “complex” domain, there is no one right answer. Snowden and Boone explain the difference between complicated and complex domains by comparing a Ferrari and a rainforest. The Ferrari is a complicated machine, but an expert mechanic can take one apart and put it back together without changing the car and its performance. A rainforest, on the other hand, is dynamic, subject to other factors in the environment like migrating animals, rain, and temperature, and is much more than the sum of its parts. Complex contexts develop because of a major change in an organization or its immediate environment that introduces unpredictability and unrest.

In the complex domain, leaders need to be patient and look for patterns to emerge in their situation before they take action. They must “probe first, then sense, then respond.” By conducting small experiments, you can test reactions without having the entire museum fail. I would argue that the museum and broader cultural sector often exist in the complex domain when we are making mission-focused decisions. We don’t produce uniform, repeatable products; we don’t have complete measures of our impact.

But when faced with making decisions in a complex situation, often brought on because of a shock to our environment (a grant is lost, a new leisure-time attraction opens, an exhibition fails to draw attendance), it’s rather difficult to be patient and probe before acting.

The temptation in complex settings is to revert to command-and-control management styles, or to drop the programs that are high on mission but low on revenue. But in actuality, these contexts are a time to experiment in small ways, to tolerate failures, and to allow the disorder to continue while searching for a new pattern to emerge. These are creative, innovative, but stressful times to be a leader.

Chaotic Contexts

A shock to our environment, like a virus that closes us all down, is beyond complex. Complex situations are challenging enough, but chaotic contexts require leading through a period of “unknowables.” These are not times to be patient and seek patterns, but times to stop the bleeding. Searching for the “right answer” is pointless. Leaders must “first act to establish order, then sense where stability is present and from where it is absent, and then respond by working to transform the situation from chaos to complexity.” This is the domain of rapid response.

We are living the definition of the chaotic context right now. Museum leaders are acting definitively by closing their facilities, laying off employees, and seeking cash-flow stability. Communication is necessarily top-down; there is little time for consultation.

As stressful as this situation is, it also presents creative and innovative opportunities—to develop or expand virtual programming, for example. The chaos domain is one of the best opportunities for leaders to motivate innovation even while they are fighting a crisis. By leaning on leaders both formal and informal inside their organization to develop solutions to keep their mission alive, they can also further develop capacities that will be vital when the chaos is resolved. So, to be clear, while rapid response is essential, reverting to a command-and-control management style will not be successful throughout this situation. These are not simple decisions that can be, by definition, controlled.

Museum Leadership Context

It is possible to face multiple contexts, or even all contexts, at once. As we opened the new science center, the Cynefin model helped me realize this, and provided me with a way to adjust my own thinking, assessment, and action. Most of the complexity of opening shifted quickly to simple decisions once we sorted through the emerging behavior patterns or disruptions to our original operating plans. The complicated new processes needed to be documented, or re-written, when it was clear that the previous systems weren’t working well.

I believe we are in such a moment now, where we are facing simple/obvious, complicated, complex, and chaotic contexts simultaneously. Complicated legislation is driving our attention to how emergency funding support may or may not come to pass. Complex decisions include which staff to retain and how to manage the internal cultural impact of layoff events. Simple issues like changes in security for our facilities in these times can take significant energy from our managers. And, of course, there is the chaos of not knowing when this might end, and what we will emerge as when it does. However, by seeing our challenges through these different domains, there is opportunity to reframe and respond with greater chance of success, now and in our future.

About the author:

Jennifer Martin is the founding, now former CEO of TELUS Spark in Calgary, Alberta. She started as an exhibit and program developer at Science North, and spent over twenty years in successive roles at the Ontario Science Centre. Jennifer now assists museum CEOs and their teams with major change initiatives and capital projects.

Further resources:

Making Sense of Complexity – an introduction to Cynefin (4-minute video)

The Cynefin Framework (8-minute video)

Skip over related stories to continue reading article

Nice summary. The framework has changed a bit since this version. Simple is now called Clear. To add to your summary, complicated is the domain of experts. Cause and effect works here. Also, disorder (now called confused) is many times forgotten in the summaries and yet we spend probably most of our time there because we don’t know about Cynefin or we don’t know which domain we are in or we don’t care to know. This is the domain where the US was for some time in between the initial outbreak and China and when we shut down flights from China. But we didn’t know we were confused so it led us in to chaos. We were In the liminal cynefin model, disorder is now split into two sections A and C. Aporetic or Confused what used to be called authentic or inauthentic disorder. (see https://cognitive-edge.com/blog/cynefin-st-davids-day-2020-2-of-n/)

Thanks Charlie. It is intriguing how much this model continues to evolve over time. A good indicator, I believe, of its relevance. Thanks for the add on Disorder/Confused.