As the world faces the unprecedented in climate crisis and pandemics, museums are more important than ever for facilitating essential human connection and meaning-making. As a result of these crises, human lifeways and ecosystems will be changed, and the impacts will vary over time and with the ability of different societal and environmental systems to mitigate or adapt. Museums have a role to play in helping people imagine and contemplate that future.

There is a close connection between climate change and pandemics. Climate change is a slow-motion public health emergency, exacerbated by health crises associated with sudden events, such as extreme weather and wildfire. The environment is one of the factors that affect our health. During the hunker-down of COVID-19, we are seeing less pollution and accomplishing a diminished carbon footprint.

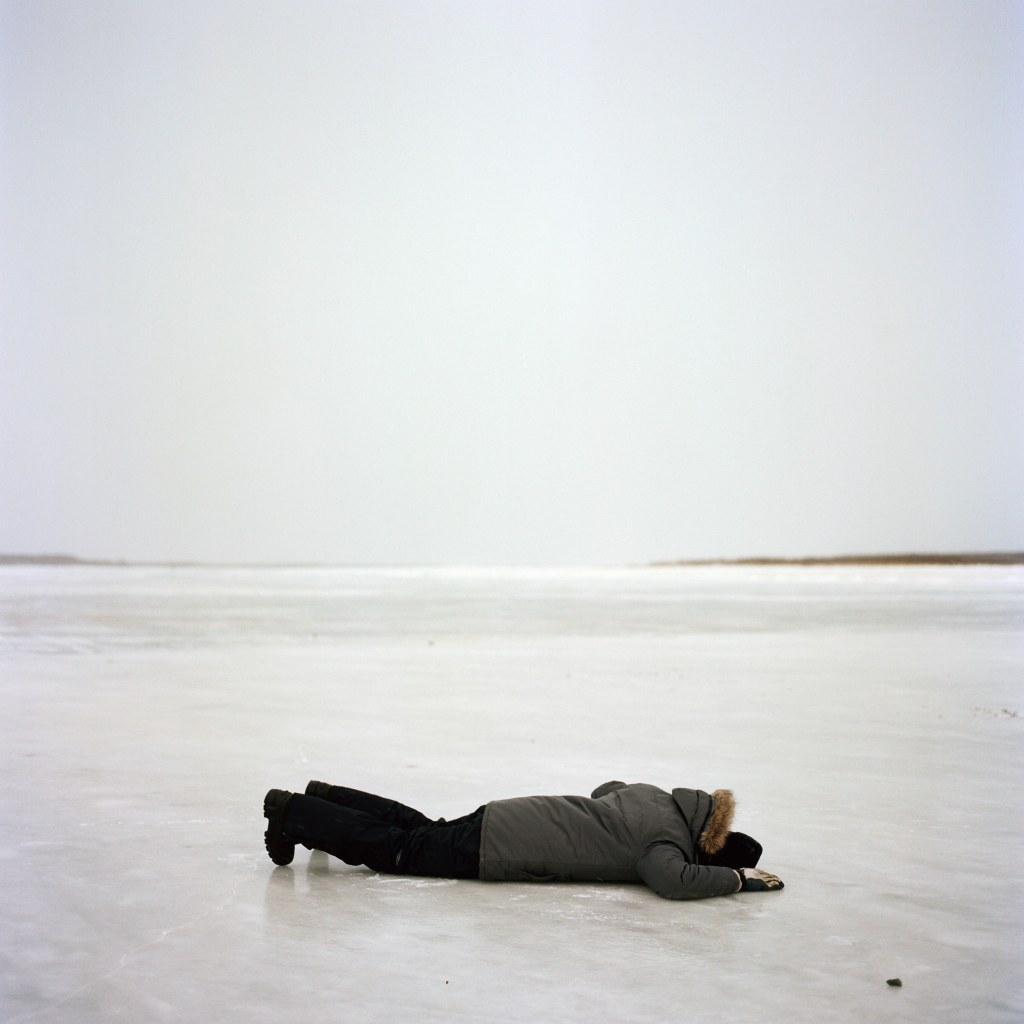

For a museum in Alaska, climate change is an especially defining issue. The Arctic is warming at an average rate twice as fast as the rest of the world and has already seen a deep impact, much of which is probably irreversible. This is a key narrative of our time, and as we offer stories and perspectives of place and people, it prompts a need to look forward, to imagine tomorrow.

At the Anchorage Museum, we work to engage the public around ideas affecting our changing landscapes by creating and highlighting radical new forms of research, practice, placemaking, and public art. We gather a rich community of thinkers, creative practitioners, and changemakers to focus on vision, problem solving, and positive change. This work falls into three primary actions: Prototype (envisioning and creating examples of future solutions), Respond (approaching the issue with language, visuals, voices, and action), and Connect (building connections between people and landscapes to help them understand and respond to change).

At the center of this work is highlighting Indigenous knowledge, place names, and voices, to expand the understanding of Northern people and landscapes and convey a pivotal and relevant narrative of the North for the world. The museum offers trainings in land acknowledgment, creates large-scale installations featuring land acknowledgment and Indigenous language, and is working with community partners to display Indigenous language and histories in public places.

Our public art and creative placemaking projects are temporary engagements and installations that begin at the museum and extend out into the city. In one project from 2019, called It is Possible, we created a series of graphic design installations throughout the city that played with phrases drawn from workshops focusing on civic solutions. These large-scale text installations appeared on the side of the museum’s SEED Lab building—an innovation space focused on community conversations and repair—and in unexpected places around the city, including a water tower, bus stops, a library, housing, a mall, and parking garages. As part of the project, the museum also worked with youth to create their own images and phrases, then produce buttons and t-shirts bearing their work, in conjunction with the Museum for the United Nations and its project MY MARK: MY CITY.

Another project, titled Hghu Hghazdatl: They All Gathered, brought together divergent communities through a series of public art installations to explore future positive design and promote a sense of belonging in the city and relating to each other, the environment, and Indigenous values. In conjunction with Anchorage Design Week 2019, the project was curated by Tiffany Shaw-Collinge of Canada and included four site-specific, temporary installations in Anchorage.

Other placemaking projects have included large-scale outdoor projections of glacier images by Alaska photographer Kerry Tasker (Cloud Chamber), an urban reforestation project (portable forest), climate walks, and projects with artists such as Mary Mattingly, who is working with the museum to inform an “ecotopian” library.

Beyond these placemaking projects, we work with artists in other ways to connect people to the natural world. For example, we are currently working with Seattle-based artist John Grade on a project titled Spark to examine the state of forest fires in Alaska and around the world. We are also collaborating with the Arctic Design Group of the University of Virginia and Lateral Office of Toronto, Canada, on projects that focus on radical research, including connecting to their work for the 2020 Venice Architecture Biennale.

With artist Jonathon Keats, we are working to develop Alaska River Time, a multifaceted artwork that seeks to bolster public appreciation of glaciers and glacial rivers (as well as other rivers in the Anchorage community) by enlisting them as timekeepers. Glaciers, in addition to being icons of climate change, are highly sensitive indicators of present climate conditions, recorders of historical climate, and predictors of climate in the future. To build people’s understanding of their significance, Alaska River Time will include public art installations, social media engagement around hypotheticals (what if the commodities trading bell ran on river time? What if our schools and semesters ran on river time? What if we punched in and out of work based on the flow of our local river?), an online river time clock, a river time parking meter; and performances, tournaments, and other events run on river time.

With Lateral North of Scotland, we are collaborating on Future: Arctic, a speculative project proposing a future Arctic Loop that will connect communities throughout the North. This circle of infrastructure, based on a “hyperloop” concept, would transport passengers, cargo, energy, water, and a host of other services, effectively replacing air travel and providing a more sustainable way of travelling. Future: Arctic puts the North at the center of worldwide transport in the future, while also exploring how the Arctic Loop will affect governance, humanity, ecosystems, resources, and connections within the region. Though highly speculative in its vision, the atlas prompts a new way of conversing about the future of the region and issues impacting climate change, including energy, food, transportation, and policy.

This year, we are also launching Future Ready, an open call that invites proposals for survival “kits” and inventions that provide readiness for a changing world. The call invites images, ideas, words, and inventions as well as survival manuals or proposals for constructions and installations—whether practical, imaginative, or speculative. We are inviting ideas ranging across all forms of knowledge and experience: art, design, creative writing, engineering, technology, fashion, architecture, medicine and more—from DIY and make-from-home, to upcycled, analog, and tech.

The Anchorage Museum also hosts major convenings, which bring community and creatives together to talk about the future and the role of art and design within a broader ecosystem. COVID-19 has initiated creative ways to convene and we will be experimenting with an outdoor and virtual 2020 Critical Futures Creative Conference in the winter, to connect from around the world to invent new language and visuals around climate change, as well as create shared experiences around contemporary art and critical thinking. We will also host a virtual and in-person convening with more than a dozen other museums, nationally and internationally, to examine ways museums can talk about climate change and contemporary issues and the environment through their collections.

In her recent Nobel Lecture, writer Olga Tokarczuk said, “Today our problem lies—it seems—in the fact that we do not yet have ready narratives not only for the future, but even for a concrete now, for the ultra-rapid transformations of today’s world. We lack the language, we lack the points of view, the metaphors, the myths and new fables. Yet we do see frequent attempts to harness rusty, anachronistic narratives that cannot fit the future to imaginaries of the future, no doubt on the assumption that an old something is better than a new nothing, or trying in this way to deal with the limitations of our own horizons. In a word, we lack new ways of telling the story of the world.”

Our future looks far different than our yesterday. Climate change and COVID-19 reinforce that we must prepare, and we must respond. As museums, we have an important role to play in our communities, to offer trusted information to navigate the present, but also to play the equally critical role of posing questions about the future and encouraging the vision and imagination needed for tomorrow. Museums help people find meaning—it is the core of our service and it is what makes us essential. We are diverse mirrors for the community to reflect the moment, keepers of the histories we should not repeat, and provocateurs of shifts in thinking and action, able to prompt and provide narratives that define the now and the next.

Here, towards the top of the world, we know that our imperative is to play a role in find new ways of telling the story of our place, and what our place might mean for the rest of the world.

About the author:

Julie Decker, an AAM member, is the Director/CEO of the Anchorage Museum. Decker’s career has been focused on the people and environment of Northern places and building projects and initiatives that are in service to local and global communities. Before becoming Director/CEO, Decker served as the museum’s Chief Curator. She has a doctorate in art history, a master’s degree in arts administration, and bachelors degrees in fine arts and journalism.

I loved every aspect of this article – the creativity, the curiosity, the confidence and courage. The future- and community-driven focus is thrilling. Thank you.

Hi! Wow! I agree fully with Sarah Sutton in the comment above! Truly inspiring! I want to take part and collaborate… Congrats, and, yes, thank-you.