Support Free COVID-19 Resources for the Field

The current crisis is taking a distressing financial toll on cultural organizations, and AAM is no different. The Alliance Blog is supported by membership dues and donations. In these challenging times, we ask that if you can, consider making a donation or becoming a member of AAM. Thank you for your much-needed support!

Last year, I began a research project on how museum audiences understand the “candy fall” installations of the artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres, which consist of piles of hard candies that are installed on the floor of a gallery space. At the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, I observed visitors interacting with Untitled (Placebo-Landscape-for-Roni) (1993)—inspecting the installation, reading the label, and hesitantly taking candy from the pile. I planned to conduct a similar study in a different location before finalizing an article. Then the pandemic hit. I’ve begun to see my research in a new light: While I expect many museums to reopen by the fall of 2020, it is difficult to imagine visitors picking candy up off a public floor and ingesting it, in the wake of new hygiene and physical distancing protocols.

As museums reopen, new protocols will need to be developed to keep visitors safe, including ways to display and interact with interactive art objects. While I want to consider some of those approaches applicable to interactive objects, I also want to reflect on how the interaction itself lends to meaning-making for both the objects and the museum space. What approaches can museums use when displaying interactive objects post-pandemic to keep audiences safe while still allowing the objects to fulfill their conceptual functions?

In the case of Gonzalez-Torres, this conceptual function relates to the politics of touch during the AIDS crisis. The early candy falls represent the body of the artist’s partner Ross Laycock, who passed away from complications related to AIDS in 1991. As visitors take and eat the candy, they are participating in a sensual and metaphorical ritual of ingesting the art “body,” which over time diminishes and wastes away, similarly to the wasting effect of AIDS on the real body. In the new world of vigilant hand-washing, mask-wearing, and physical distancing, touching and tasting an unfamiliar body seems unimaginable. So, if the candy fall pieces are shown when museums reopen, I suspect they will remain mostly untouched, and museums may even choose to rope them off to prevent contamination.

For works like these, which specifically relate to wellness and sickness, museums could offer special educational and interpretive programming to emphasize their relevance to the current crisis. Many museums have items in their collection that directly relate to previous pandemics, like the AIDS pandemic or the 1918 flu pandemic. For instance, the artists Edvard Munch and Egon Schiele were impacted by the 1918 pandemic, and Schiele and his wife Edith died from it.

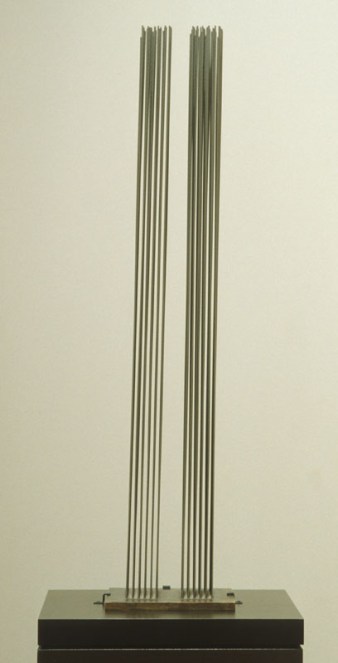

While some pieces may retain or gain new meaning regardless of whether direct interaction is possible, others will suffer if they are completely sequestered. Consider a sculpture like untitled (musical sculpture) (1968) by Harry Bertoia, which appears in the galleries of the Spencer Museum of Art at the University of Kansas. In this work, numerous thin metal rods project vertically from a plain black base. The piece comes to life when viewers move their hands through the rods, putting them into motion and emitting a warm trilling sound. Without touch, this object will not perform its intended function, as visitors will not experience the vital component of sound.

Works like these require activation to be meaningful, but it will be hard to allow that safely in the near future. We know the virus that causes COVID-19 lives longer on hard surfaces than other materials, and methods for disinfecting artworks are limited and likely to lead to unwanted wear. One option could be to require visitors wear disposable gloves to interact with the sculpture, but these are in demand as personal protective equipment for healthcare workers, and would lead to other issues like educating the public on their use, finding funding for them, and ensuring their proper disposal.

If these issues prove unfeasible, pieces like untitled (musical sculpture) could be used in educational programming where the sculpture would be demonstrated by museum staff only, to limit the public interaction with the object while still showing how it performs. Or, to limit touch even more, museums could film a video of the object in action and display it nearby, which could be featured on social media or the museum’s website for broader access.

But solutions like gloves or videos are not appropriate for all works. For example, Yoko Ono’s “instruction paintings” are small square artworks created from several printed pages bound together, each of which contains the same conceptual instructions to the viewer on how to create an artwork. The pages are perforated at the top, and visitors are invited to tear off and take a page from the piece.

Because they are made of paper, these “instruction paintings” would be difficult to sanitize. While museums could request visitors use gloves to touch and tear the piece, visitors are still intended to take the paper with them, leaving room for possible transmission when visitors need to remove the gloves.

If a museum is not able to show interactive works as intended by the artist, particularly those like the instruction paintings that cannot be meaningfully displayed without touch, should they be shown at all until the pandemic has concluded? Regardless of when that is, how long will it take for visitors to feel comfortable touching public objects again?

As my research with the Gonzalez-Torres works showed, interactive objects can have a significant impact on visitor experience and understanding, changing how visitors relate to works and perceive museum spaces. With the candy falls, the relational aspects of the work and the challenge to normal museum protocol struck the visitors as most important. After hearing or learning about the background of the piece, many visitors stated that they related to how the work “shared the self” with others, and saw this sharing as a token of care or love. The majority of their comments also touched on how the invited interaction upset museum protocols and allowed visitors to have unique experiences of both art and the museum space. Visitors were excited by the invitation to be active in the space and participate in the meaning-making of the work. Their interactions with the piece were central to their understanding of the content.

To make sure this experience is preserved as much as possible, museums will need to continue to be innovative in their solutions for visitor access and education. Incorporating modified educational programming, new safety protocols, and object-specific digital tools long-term will aid in allowing visitors to experience interactive works safely and meaningfully.

About the author:

Rachel Trusty is a doctoral student in Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at the University of Kansas in Lawrence, KS. She received her MFA from Lesley College in Boston, MA in 2011. Trusty’s dissertation research examines the historical discourse around and audience understanding of art created by LGBT+ artists.