During this time of crisis, it has never been more important to center access, equity, and inclusion in our response to the unknown. As we adapt quickly and shift our focus online, it is essential that we prioritize and commit to accessibility and inclusion in the digital space. At Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, we’re considering: Do our events and videos have captions? Are our institution-wide updates about museum operations written with plain language? Are our digital resources accessible to visitors using assistive technology?

Significant work for us to commit to in this moment is the practice of image description. Cooper Hewitt’s website hosts countless images—not only of the more than 210,000 objects in our collection, but also of events, programs, exhibition installations, and products sold at our museum store. For our online experiences to be equitable, each of these images must be described. Image descriptions are used by visitors navigating websites with assistive technology, or by anyone interested in exploring online content through another entry point.

In the last few years, we’ve laid a foundation for this practice. We’ve raised internal awareness through trainings and provided image descriptions in our newsletters and on social media. We’ve kept up with our colleagues at peer museums and incredible artists who have led projects with similar goals. Still, before we shifted to remote work during the pandemic, only a small percentage of images on our site had been described.

We had a simple premise: a group of staff would join the image description project; each week they would describe some images; and slowly, incrementally, we’d chip away at the 210,000-plus images.

In the first three weeks of the project, a team from visitor experience, digital, SHOP, exhibitions, curatorial, education, and the library authored 842 descriptions. We are encouraged by how the project has been received, how it has opened up fascinating, unexpected conversations, and how it has brought together a team that might not normally work together. 842 descriptions are important progress, but just the beginning of work to be done. We’re eager to keep this practice going and to share our lessons along the way. Here’s some of what we’ve discovered so far.

Set Intentions, Not Compromises

At the onset, we had to think about how best to proceed. How could we respond quickly, using the moment we were in as an opportunity while ensuring that we were honoring the people, work, and process involved along the way? We had to balance our feelings of increased urgency with acknowledging that this work had always been critical and deserved to begin with an energy and attitude that reflected its importance.

We had some resources in place, essential support within Cooper Hewitt and the broader Smithsonian, and we were ready to make progress. Now all we had to solve for was: Which staff members? Which images? And how would we keep it all together?

The project began with a core group that consisted of frontline staff—folks who held roles centered on the physical museum—in visitor experience, SHOP, and AV. As a group, we spoke about the values behind the project, what the work meant and what form it would take, and how we would collaborate. We held virtual meetings to demonstrate the software involved, practiced describing some images together, and asked any questions we had. Then we got started.

We had simple ground rules. Staff were welcome to contribute as much or as little as they could each week—no judgement. We trusted the team to show up with us as they could and honored their energy when they did. We ran the project in weekly “sprints,” in which everyone in the group selected the images they wanted to work on from a strategically prioritized set of objects. We prioritized objects that are featured in current and upcoming exhibitions, or that are available through Smithsonian Open Access. For each object, we asked everyone to create two descriptions: a long and a shorter “alt” description.

While we were enthusiastic to work through the images, we knew it was not the moment to compromise on quality. Rather than approaching this as a “box-checking” exercise, we needed to take time. Since museums use images on websites and other digital platforms specifically as a form of deep meaning-making, exploration, and engagement, we recognized that a thorough description would be necessary to convey the complexity and nuance present in object images. We knew that if we were committed to prioritizing this work—if we were going to ask our colleagues to give their time and effort to it—we had to ensure we were setting out to do it the right way.

Democratize “Expertise”

A core belief we hold about image description is that all members of staff bring a valuable perspective to it. Any member of staff can join the practice by bringing their unique perspective and giving careful, concerted effort to authoring. Through participating in trainings, practicing the skill, and engaging in ongoing conversations around the work, anyone can develop an expertise in authoring descriptions.

We also know that visual descriptions are inherently subjective. Descriptions are enriched through intentional, considered choices of words and metaphors, which are unique to each of us—there is seldom a single “right” answer. In discussing, debating, and interrogating our descriptions as a group, we opened a rich discussion on language and how meaning is formed through images.

As we established a framework for our descriptions, we started from the following questions:

- What is important about the image?

- What word choice best conveys the visual elements?

- How can we use language to best reflect the impression / intentions of the image?

To support other organizations in doing this work, Cooper Hewitt published Guidelines for Image Description, a document developed by our friends Sina Bahram, from Prime Access Consulting, and Anna Chiaretta Lavatelli, an independent museum professional and advocate. We hope this resource may serve as a starting place and support those who, like us, hope to center on inclusion.

Work in Community

At Cooper Hewitt, we’ve learned that improving accessibility and inclusion happens most effectively when they are shared values rooted in the ethos and culture of the museum—and when they are something everyone actively participates in. So, for our project to be successful, we needed to build a community of practice around it.

Typically, image description authoring is done in isolation, where one sits with images and describes. In most instances, visual descriptions are the responsibility of communications or digital staff members who input descriptions or “alt” text directly when editing web content. Instead of this, we wanted to embrace a creative and collaborative method centered on the act of gathering (for the time being, virtually) together.

This was essential for a few reasons. First, our once in-person team was working at a distance and we knew it was important to bring people together to engage meaningfully with our collection. We wanted to create space to gather together regularly and to do so specifically in a context that was generative and mission-driven. During bi-weekly project meetings, we discussed, asked questions, and determined a workflow for reviewing and approving descriptions to ultimately be published on the museum’s website.

Additionally, we recognized that descriptions are inherently enriched through discussion—more perspectives offer deeper understanding of images. We leveraged the diversity of expertise within our team. Anyone, no matter their designated role at the museum, brought valuable insight to the experience of an image and the resulting descriptions offered nuance and layered understandings that were well-balanced and informed by various points-of-view.

Our gatherings also kept (and continue to keep) us fueled and motivated to do the work. We held each other accountable, and we practiced what it meant to create a safe dialogue around challenging topics, to learn and work through them as a group. We welcomed sharing, debating, and questioning; we embodied a collective learning mindset in which we could work through problems together.

We worked through some hard questions, such as:

- What word choice feels right?

- What are we assuming?

- How do we describe what is ambiguous to us?

- How much design vocabulary is meaningful to include?

- What are we prioritizing in the hierarchy of an image?

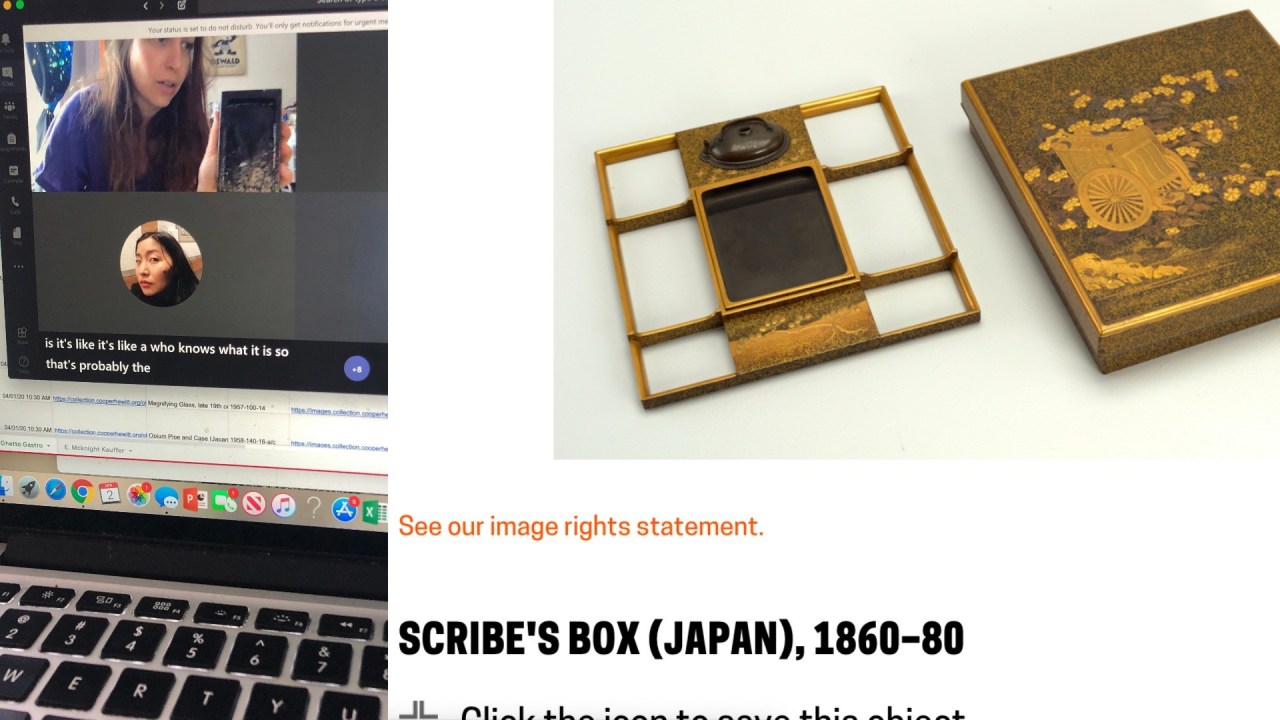

Each week, we brought objects to the group that posed difficulty and crowdsourced their descriptions. During an early gathering, for instance, a member of our visitor experience team brought an image of a nineteenth-century Japanese scribe’s box for discussion. The box had an inlaid pattern that was straightforward, but its construction and interior components were difficult to comprehend from the image. Immediately, a member of our digital team rummaged through her apartment and found several of the pieces from her own scribe’s box—an artifact from her studies abroad. She continued to articulate each part, describing the materiality and intended uses, and the group drafted a description accordingly.

As we worked through these difficult topics, we documented our discussions and the answers we arrived at. The resulting resource has guided us on subsequent descriptions and continues to be updated to reflect our ongoing conversations. Upon requests, we’ve invited in other voices—curators and content creators who shared thoughts, frameworks, and language to consider—to add to our record as we hone our “voice” and continue to describe.

Make it Fun

Cooper Hewitt’s collection is home to objects fantastical, unusual, and outrageous—many of which staff never have the opportunity to deeply explore. So, in addition to the images we prioritized, we asked the team to dedicate one object each week to respond to a weekly challenge prompt. The prompts were lighthearted, instigating, and ultimately intended to invite a little playfulness and deep-diving into exploring the collection.

The team responded to a guiding prompt:

- What will keep you cozy at home on a rainy day?

- I Spy: an object you have at home?

- An object you’d like to have if marooned on a deserted island?

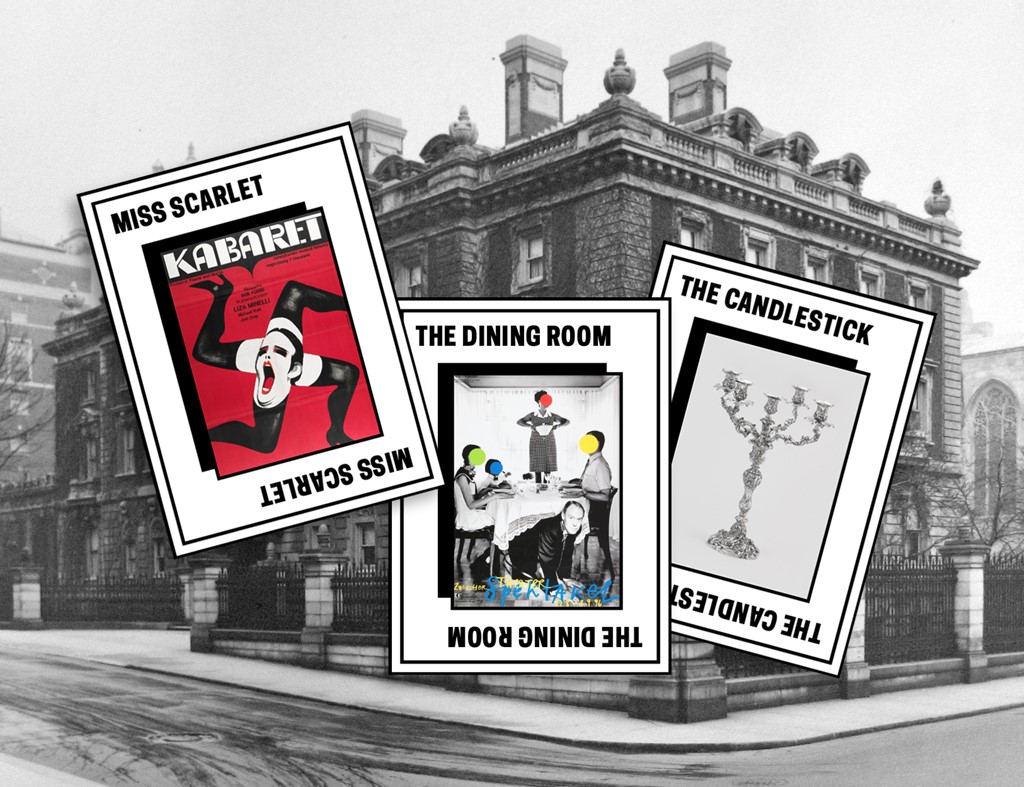

- It was Miss Scarlett, in the dining room, with the candlestick. Something red, dining-room related, one of the 243 results when you search “candlestick” in our collection?

During our virtual gatherings, we shared our findings and opened up through personal stories about family, opinions, memories, or wishes—creating moments to laugh and connect beyond the work. We learned about each other, and about areas of the collection that many staff would otherwise not have reason to explore. We made space for building connections, both with each other and back to the museum.

Create Pathways to Sustain

Now that our staff participated in training, came together in discussion around descriptions, and had momentum doing the work, we thought about making sure the practice would be sustained. What foundation would we need to lay to ensure an effective transition in the future? In developing a strategy, we considered:

How will this new community continue to gather?

Are there digital tools used in our organization that serve cross-departmental staff? Does everyone have equal access? As we develop our transition approach, we are considering how to maintain mechanisms for the group’s ongoing communication, and ensuring opportunities to regularly come together (physically) around the work. We also are continuing to formalize our style guide—refining it following each discussion to inform future descriptions.

System integration

How do current digital systems store and deliver descriptions? Is this the same across platforms or unique to each one? Authoring descriptions is a necessary creative practice—but ensuring that descriptions are stored and implemented across platforms is critical to the effectiveness of the approach. Cooper Hewitt’s approach to this is to use Coyote, an open-source software that provides a description repository and allows for a more robust workflow in authoring, reviewing, and approving image descriptions developed initially in partnership by Prime Access Consulting and the MCA Chicago. This carefully thought out strategy involves combining effective technical tools with an understanding of best practices and workflows to make sure the project can be scaled and continued.

Conceive the Future

The work we are doing today is determining the future we will arrive at when our museums physically reopen to the public. As we each grapple with these new realities, I was immediately struck by disabled activist, writer, and artist Sharona Franklin’s work about our moment.

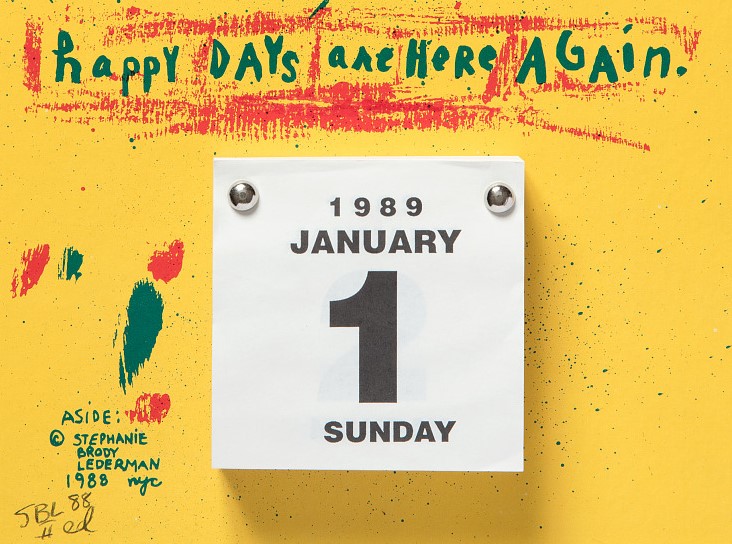

In the midst of everything happening, some might forget that this is a landmark year commemorating the thirtieth anniversary of the passing of the Americans with Disabilities Act. In the three decades since, disabled people have continued to protest, advocate, and fight for equity—particularly now, as this time of crisis disproportionately affects this community. Also, notably, the year after a Supreme Court case denied a pizza company’s outrageous claim that the ADA didn’t apply to websites. So, if you’re looking for ways to acknowledge #ADA30 this year, why not start with some image descriptions?

It is a privilege to be able to use a time of crisis as a catalyst for work. Many inequities carry into this moment, and many more are created or amplified through the uncertain circumstances we are in. As such, there has never been greater urgency for those of us with this privilege to bring forward meaningful, inclusive work. The values we center on, the work we choose to prioritize, and how we move it forward shapes who we will become as institutions. This is the moment to center access, gather together, set intentions, and have some fun while we do it.

Deepest gratitude to the following for contributing to this work:

This work is only possible through the intentional, intellectual energy of CH’s incredible staff and committed leadership team. Deepest gratitude to our dedicated community of describers:

Alessia, Alexsander, Angel, Angela, Amanda, Cat, Charlotte, Cindy, Carolyn, Daniella, Devon, Emily B, Emily R, Joseph, June, Katherine, Kathleen, Kendra, Kirsten, Matt F, Matt S, Mauricio, Miguel, Mir, Nilda, Rachael, Robyn, Shamus, Stephen, Suzy, Tara, Valarie—this work exists because of each of you.

This work is created through essential partnership with:

Access Smithsonian, Beth Ziebarth, Jacob Kim, Ryan King, Anna Chiaretta-Lavatelli, and Sina Bahram—my deepest admiration to your guidance without condition, insight, and promise to this practice.

This writing was made better by invaluable thought-partners and expert wordsmithers:

Hannah, Joseph, Pam, Rachel—my personal thanks to each of you for helping tell this story.

About the author:

Ruth Starr is a cultural practitioner currently serving as Accessibility Manager at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Trained as an American Sign Language-English Interpreter, Ruth’s work explores ethical frameworks around allyship and the role of language and perception in meaning-making.