This article originally appeared in the September/October 2020 issue of Museum magazine, a benefit of AAM membership.

How can museums nurture the next generation of citizen-leaders?

“Why does it even matter?”

As a middle school history teacher, this was the sort of question I would typically field during the first week or two of school. Math and language arts are on all the big tests. Mastery of science can lead to careers that pay well.

History, though . . . why does it even matter? Often, I’d throw the question right back at the class. The answers were broad:

- So we don’t repeat the mistakes of the past.

- I need good grades to get into college.

- It’s fascinating. I saw it on the History Channel.

- Because you said so.

- Ugh. Don’t make me think.

Though it’s been a decade since I left the classroom, I’m still responding to that question through my work at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Institute in Simi Valley, California.

Quite simply, history matters because the context of the past allows us to thoughtfully address the challenges of the present. We stand on the shoulders of those who’ve come before us, and with their wisdom, guidance, and knowledge of what they did to make progress, we have a template for moving toward that “more perfect union.”

Our education mission at the Reagan Foundation is to cultivate the next generation of citizen-leaders. Here are a couple of the ways we are using history to help students become more civically minded.

The Power of Simulation

In 2011, a group of leading civic learning scholars published Guardian of Democracy: The Civic Mission of Schools. This landmark report detailed six proven practices that support effective civic learning. Proven Practice #6, Simulations of Democratic Processes, helps develop civic knowledge and skills because games and simulations can be highly engaging and motivating. “[S]tudents learn skills with clear applicability to both civic and non-civic contexts, such as public speaking and teamwork,” according to the report.

The concept is not new: learning through doing has been around forever. And museums can offer immersive learning environments, through the use of artifacts or replicas, that a traditional classroom can’t. The replica Senate chamber at the Edward M. Kennedy Institute for the United States Senate, the lunch-counter interactive at the National Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta, and the Star-Spangled Center at The Magic House in St. Louis are just a few of the many immersive simulation environments at museums.

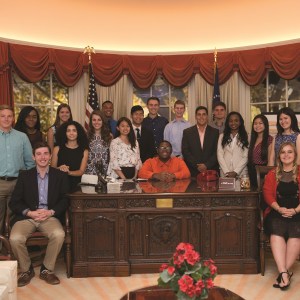

At the Reagan Foundation, we offer the Air Force One Discovery Center, where more than 25,000 elementary and secondary students each year can simulate decision-making and collaboration at the highest levels of government, the media, and the military. Students take on the roles of the president and his advisers in the model of the Oval Office, of the chairman of the Joint Chiefs and military advisers in a Command Decision Center, and of correspondents in the White House press room.

The simulation hinges on a news report that the US is preparing to send the military to Grenada, which means a top-secret mission is now public. Students get information from a variety of news and national security sources based on their specific role and then recommend a course of action. There is no clear and unambiguous right answer; students must make tough choices and defend their reasoning.

The students discuss two important American ideals that often come into conflict with one another: freedom of the press and national security. Our educators lead a debrief discussion that brings this clash to the forefront and encourages teachers to continue the discussion back in the classroom.

For the purpose of this simulation, our team prioritizes the process of critically thinking through a decision rather than a specific outcome. While we want students to leave with an accurate understanding of what decisions were made in history, we focus on giving students an opportunity to develop their civic skill set. We want them to grapple with conflicting values and pieces of information and make a tough decision.

Far too often in the real world, issues are portrayed as overly black and white. We believe the gray is the best place to learn. Of the more than 500 teachers who have responded to our exit survey, more than 99 percent report that the learning experience in this simulation met or exceeded their expectations.

In the museum tour that accompanies this simulation, we strive to make connections for students. Of course, our museum tells the story of President Reagan, but it also tells the story of our country during his lifetime and how an individual can effect change. We don’t just want the students to learn this story and leave the museum with a long list of facts. We want them to connect to the story, to understand that they too have power and influence as civic actors. They too can lead and influence others in their home, at their school, and in their community.

The Building Blocks of Leadership

Following her retirement from the Supreme Court, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor founded iCivics, an interactive, game-based website that teaches civics and government to millions of students each year. In early 2019, iCivics hosted a convening of researchers, funders, and programmers to talk about what works in civic learning. To provide a theoretical backbone for the convening, The Center for Educational Equity at Columbia University summarized the prevalent research, which finds that the same skills and values that make someone a good citizen—self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, and responsible decision-making—also make them a good person, a good community member, and a skilled member of the workforce.

This begs the question: How can museums leverage their collections and programs to help develop these skills and mental habits? We are trying to find out through our Student Leadership Program (SLP), a week-long summer camp where high school students identify an issue that they would like to address at their school or in their community.

Over the years, these issues have spanned the spectrum of civic-mindedness, including organizing supplies for wounded veterans, forming anti-bullying clubs, distributing personal care packages to the homeless, and more. Whereas the tours with the Discovery Center leverage the idea of plugging into a broader civic and American narrative, the SLP allows students to dive deeper into self-assessment and civic skill-building activities that provide a toolkit for effective civic action.

At the end of their week in the program, students present their plan of action to a community mentor—local leaders of businesses, nonprofit organizations, schools, and the government—and get feedback on how best to implement their plan. In brief, here are four ways in which we cultivate the students’ civic skill set during the SLP.

Self-Assessment: We use The Personality Compass to help students better understand themselves and others. After answering a series of questions, they are assigned a point on the compass based on their responses. North is goal-centered and confident. West is creative and energetic. East is analytical and logical. South is sensitive, patient, and generous. Students then learn about the typical characteristics of each quadrant and how they can better understand both themselves and those who are not like them. It teaches both independence and interdependence, two incredibly important civic skills.

Responsible Decision-Making: Once students have their idea, they must research it thoroughly. What are the root causes of the issue? What other organizations on campus or in the community are already working to address the issue? Who are the right people at school or in the community to contact? What solutions would be most effective long term? Under the direction of interns and staff advisers, students conduct this research and ultimately decide which actions to take, which stakeholders to engage, and what timeline is reasonable. They put together a set of SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and timely) goals, which we tell them at the program graduation is only the beginning.

Communication: The ability to effectively communicate with others to inspire change is key to effective civic action, so we help students improve their communication skills throughout the week. Early in the week, they work with a group on their ability to sell an idea to a Shark Tank–like panel of potential investors. Later, and on their own, they develop an elevator pitch laser-focused on why their researched idea is important. Finally, they pitch their fully fleshed-out plan to a respected adult they don’t know from the community. Though this makes them slightly nervous, it is also a safe way for them to practice their civic skills with something real at stake.

Leadership Ladder: Finally, we know there is a difference between a single civic action (a vote or donation) and sustained, impactful civic action (starting an organization, enlisting volunteers for an extended period of time, working to advance a piece of legislation). We want our students to be able to develop their skills over time. With SLP, students can start as a camper, return as a leadership ambassador (who supports students and the interns who facilitate the program), and return again as a lead ambassador (who has some managerial duties). In college, they can return as an intern (who facilitates the program under the guidance of our education staff) and finally as a lead intern (who oversees the other interns and mentors the ambassadors). In this way, we provide opportunities for students to level up their leadership.

Students who’ve graduated from the program recently have planted acorns to help rebuild the land after destructive Southern California fires, started clubs to address mental health and anxiety on their high school campuses, worked with local banks to teach financial literacy to students, and taught students CPR.

In short, they’re becoming the sorts of engaged citizen-leaders our community needs.

Spectrum of Civic Learning

Civic learning is much more than simply sharing the stories and artifacts of our collective past. Below, I connect the research on effective and impactful K–12 civic learning to the work of museums.

Civic Knowledge: This is the basic unit of civic learning: facts, stories, artifacts, pictures, exhibits, primary source materials. For museums, civic knowledge is our collections and the stories we tell about them.

Civic Mindset: When museums leverage their collections and programs to promote mental habits like self-awareness, social awareness, political awareness, tolerance, and empathy, they contribute to the creation of a civic mindset.

Civic Skill Set: When museums leverage programs or exhibits to help visitors develop their communication skills; offer democratic simulations; promote models for effective dialogue around controversial issues; or model how to gather, analyze, and apply data on civic matters, they help their visitors develop the skills that will make them effective citizens.

Civic Action: Ideally, civic action occurs when our visitors and community members apply the knowledge, mind-set, and skill set they’ve learned in museums and beyond. Civic actions include voting, volunteering, hosting public meetings or forums, community service, and exploring current events and their impact.

Resources

Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools, Guardian of Democracy: The Civic Mission of Schools, 2011 carnegie.org/publications/guardian-of-democracy-the-civic-mission-of-schools/

iCivics icivics.org

Peter Levine and Joseph Kahne (eds.), “Civic Learning Impact and Measurement Convening: Research Summary,” Center for Educational Equity, Teachers College, Columbia University, 2018

Tony Pennay is chief learning officer of the Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Institute in Simi Valley, California. His book, The Civic Mission of Museums, will be published by AAM in the fall.

Comments