It’s well-documented by this point: museums are changing. No longer solely repositories of information and keepers of culturally important artifacts, museums today are taking on new roles and shaping revised definitions of community-building and informed collaborative programming. As part of this change, institutions with works by Indigenous and other source communities (groups from which collection items originate) are increasingly recognizing community expertise as critical to all aspects of responsible museum work, from collections documentation to public programs, exhibits, conservation, and education. But what does it mean to truly collaborate? How can we advocate for a collaborative model of museum work and proactively embrace this paradigm shift? And how can museums build positive long-term relationships with community members?

In an effort to address these questions, the School for Advanced Research—a nonprofit in Santa Fe, New Mexico which stewards a collection of nearly twelve thousand works of Native American art spanning the sixth century to the present—has worked for nearly a decade to develop the SAR Guidelines for Collaboration. A revised version, released in the fall of 2019, focuses on a practical approach to improving representations of cultures, providing meaningful access to archives and collections, and rethinking collections stewardship, all through collaboration with Native American and other source communities.

The initiative began in 2012, when consultant and conservator Landis Smith saw a need to take stock of the current state of collaborative conservation in museums. Over decades of working with various museums in Washington, DC, and Santa Fe to implement such methodologies, Smith observed that the notion of collaboration varied greatly and believed that SAR would be an ideal venue to explore the future of this type of work. She approached Cynthia Chavez Lamar, then director of the Indian Arts Research Center (IARC) at SAR with an idea for a seminar, along with a proposal to develop a resource to help guide the collaborative process. This developed into a platform that would be continued by subsequent IARC directors Brian Vallo and Elysia Poon, and would eventually involve over sixty tribal and non-tribal museum professionals as contributors.

Although the guidelines are geared towards work with Native American communities and collections staff, they can be broadly applied to a range of communities whose cultural materials are held by museums. “It is our hope,” Smith notes, “that museums and cultural institutions will consider the guidelines in the work that each department does. From collections care to docent training, there are concepts in the guidelines that can improve the working relationships across all aspects of museum work.” In just the few examples that follow, they have been applied to exhibition development, collections management and care, and museum professional training.

Exhibition Development

Skip over related stories to continue reading articleFor those who implement the guidelines in exhibition development, one clear outcome is mutual learning. Nearly every curator has experienced an exhibit narrative shifting in direction after collaborative consultation. Tony Chavarria, the curator of ethnology at the Museum of Indian Arts & Culture (MIAC) in Santa Fe and a contributor to the current guidelines, has been incorporating approaches from the guidelines at MIAC for years, most recently in the major overhaul and reinterpretation of the museum’s primary long-term exhibit, Here, Now and Always. Based on years of collaboration among Native American elders, artists, scholars, teachers, writers, and museum professionals, the new installations will feature voices of Native Americans who will guide visitors through the history and contemporary circumstances of the Southwest’s Indigenous communities and the region’s challenging landscapes along with a range of historical artifacts and works of art.

Chavarria explains that some of the community members collaborating on the exhibit had never worked with museum staff before. Even identifying the professional roles within the organization was foreign to them, so the guidelines, which could be provided to both staff and community members in advance of any working sessions, helped set up expectations and ease potential misunderstandings.

“If a museum is receiving visitors and consultants to talk about a project, the guidelines help staff consider how to not overwhelm them. For lack of a better word, how not to be too museum-y. You don’t just bring people in and bring out the gloves or even lab coats and then just go into talking jargon about the work without properly setting the place, setting the experience, building the experience up,” he says. “Basically, for us, we start out with refreshments and just talking. We go over the plan for the day and the goals for the day. We find this helps both sides because there are definitely common interests and goals. This is a way that people can meet in a way that is not intimidating and it’s not really arduous on either side.”

Collections Management and Care

At SAR, the process has helped improve collections management and care. Through a program known as collection reviews, the IARC staff arranges for tribal members from a variety of backgrounds to come to the institution in smaller working groups to review sets of objects. To date, this process has helped improve the documentation of over fifteen hundred works from the Pueblos of Zuni, Acoma, and Tesuque.

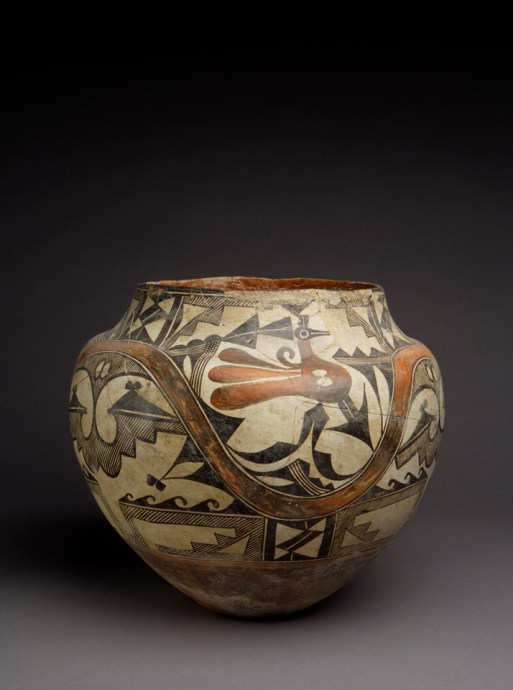

Stephanie Riley, SAR’s registrar for cultural projects, points to a specific collections review moment that illustrates the power of working collaboratively with source communities. During this review, the staff had set out a water jar from Acoma Pueblo (SAR collections number IAF.180). The staff and tribal members began to look at the piece, holding it, turning it over, and pointing to the various design motifs. They reviewed the existing collections record and noted that the bird image depicted on the face of the jar was identified as a parrot.

As the group began to discuss the work, Stephanie noticed several members beginning to speak Acoma in an animated and joyful manner. After some discussion in their native language, one of the participants shared with the staff, “We think this is not a parrot but a roadrunner.” The roadrunner—distinctive and native to New Mexico, with its long tail feathers, streaks of black and brown across its back, and unique dark feathers along the head—could in fact clearly be seen on the piece. The staff wrote down the information, corrected the record, and later followed up with the community members to share the revised records and continue the conversation about next steps in the ongoing partnership.

This may seem like a small example, but several special things happened here: community members were able to express their opinions using their native language; they felt empowered and heard when they identified materials originating from their own ancestors; and the collections team was able to correct the record for future researchers, museum professionals, and artists who might someday reference that work. Had the review not been set up in a collaborative fashion, this piece of information might have been lost, and any future researcher studying parrot or roadrunner depictions in Southwest pottery might have either referenced the work mistakenly or missed the opportunity to reference it.

Another example of the ways collaboration can improve work within the arena of collections management comes from Chicago’s Field Museum. At the museum’s Gantz Family Collections Center, the head of anthropology collections and collections manager, Jamie Kelly, and anthropology collections manager for North America, Jamie Lewis, have implemented aspects of the guidelines in their collections care work. “The guidelines informed how we can improve our hospitality when community members visit collections at the museum,” they note. “For example, we now provide community visitors with a two-page informational packet before they visit collections so they know what to expect during a visit. We also make sure they have space and time to prepare, reflect, or cleanse after they arrive, as these visits can be an overwhelming experience for some. We have also taken steps to reduce some of the bureaucratic obstacles to accessing collections, such as simplifying our Visit Request Form, which is used to record visitors to collections.”

For the Field Museum team, the work goes beyond practical improvements and addresses larger questions about their ethical responsibilities as stewards of works that originate in diverse communities. “Over time our relationships are deepening and becoming more collaborative, benefiting community members, the collections, and museum staff. We acknowledge that collaboration is critical as we continue to work with communities on how to best care for their heritage.”

Professional Training

Finally, the guidelines are helping to train the next generation of museum professionals. Ellen Pearlstein, professor of information studies at the UCLA/Getty Program on the Conservation of Archaeological and Ethnographic Materials, uses them in her courses about conservation practices. “The guidelines,” she says, “teach young conservators about how emotional and surprising it can be to discover one’s own heritage in unexpected places and how harsh the lab environment can be to community members.” She adds, “In my instruction at UCLA/Getty I incorporate guidelines principles by including Native instructors in the teaching practice, and by working with tribal cultural centers and museums in a long-term collaboration to build relationships and illustrate first-person representation to students. This instruction inspires respect and hospitality in young conservators and moves students away from jargon in reporting practices.”

Before undertaking a collaborative effort, museums should consider the reasons for the effort and the resources needed to commit to it. As the introduction to the guidelines advises, “True collaboration does not happen immediately—it is process driven and takes time and commitment. The specific manner in which you collaborate will be unique to your museum, the community, and the project. Do not confuse collaboration with a single invitation to view or comment on collections, or to rubber-stamp exhibition content. Collaboration is about sharing both authority and decision-making and includes cooperative planning, definition of outcomes and roles, task accountability, transparent budget discussions, and a clear structure for communication.”

As we move forward, how will museums and other collecting institutions elevate the voices of source communities in exhibitions, programs, and collections care? By adopting strategies to improve representations of cultures and access to archives and collections, and by addressing shared perspectives in collections stewardship, museums and their staff are responding to this evolution in the field and helping build better relationships and collaborations with communities. Ultimately, the guidelines are about building relationships. “The foundation of the work,” says IARC director Elysia Poon, “is trust. This is really the core to successful collaborations.”

Thank you very much for sharing these interesting experiences.

I am in the process of developing a means of archiving the work of Los Angeles artists of the 60’s, 70’s and 80’s who were active as LA moved to a major position in the art world. Most of these artists (especially women artists and artists of color) were not recognized in those day and few, going forward. These artists are aging and beginning to die and, for the most part, they have no viable means of preserving the artwork still in their possession. I believe these artists’ work are deserving of remaining in the public realm, being available for consideration over time and providing a valuable source of community identity even if not all of them are “museum quality”. Can we discuss how your work with cultural artifacts might apply to the “clusters of cultural art concentrations” in Los Angeles’ multi-cultural communities?