I have been wishing everyone HAPPY NEW YEAR (in all caps) because I am so relieved to see the backside of 2020. But “better than last year” is a very low bar indeed, and we face many very hard months ahead. That being so, my focus this year will be on helping museums plot their best possible course through the remainder of the pandemic, and, I hope, mitigate the damage to their staff, their communities, and their operations. This will take the form of tools, updated scenarios, and posts exploring strategies museums and other sectors are deploying to navigate the challenges of 2021.

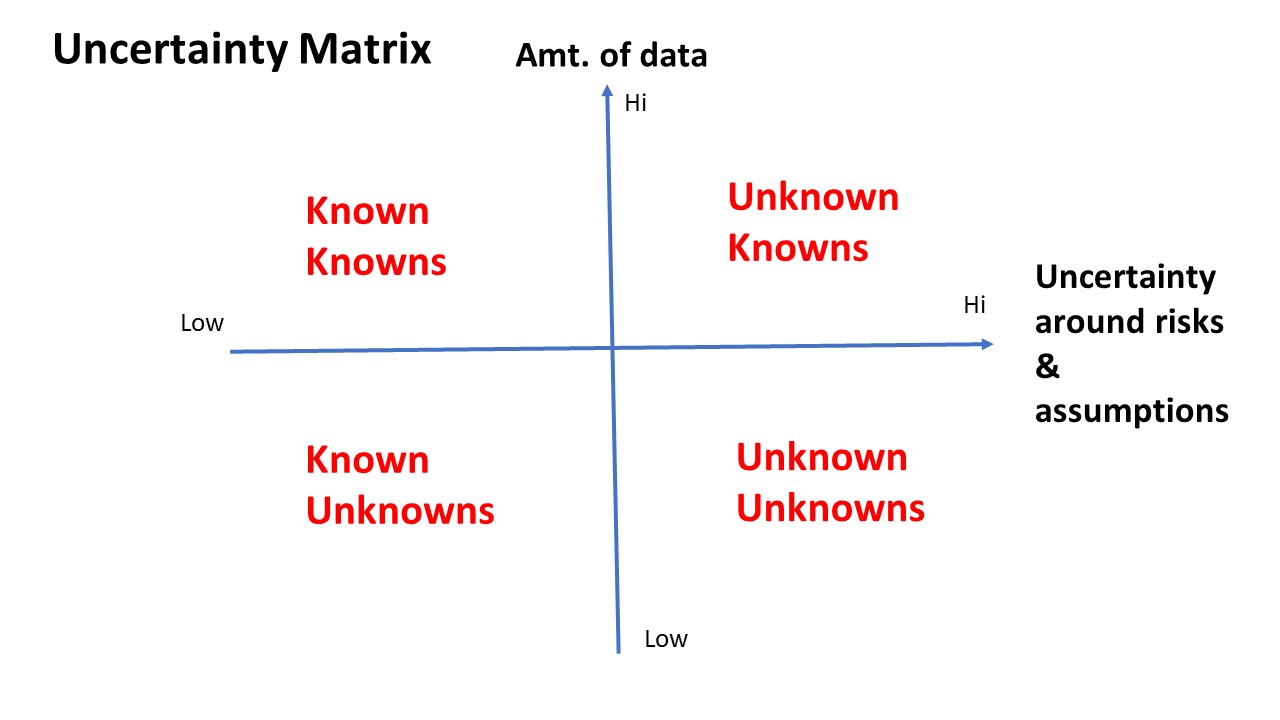

First up, I’d like to draw your attention to the “uncertainty matrix,” a planning tool that Stephen Wunker recently explored in an article for Forbes. This matrix can scaffold the creation of scenarios by sorting issues into categories based on availability of relevant information, and on the degree of uncertainty about risks or validity of assumptions. These two axes create four quadrants some blessed person dubbed the known known, the known unknown, the unknown known, the unknown unknown.

I want to acknowledge that these are terrible names for categories. They are ridiculous without being memorable or self-explanatory. (Unlike, for example, “Cone of Plausibility,” a piece of futurist jargon which is funny, intuitive, and catchy.) That aside, there are several ways of interpreting these categories. Below I outline the version I use for scenario planning and populate each quadrant of the matrix with some issues and challenges relevant to museums in the coming year.

Known Knowns

If you know an issue is important, and you have the data you need to assess its status and impact, that issue lies in the comfortable realm of “known knowns.” For museums one sterling example is your financial status in the short term. To assess this issue you may turn to data such as:

- Months of operating reserves remaining on hand

- Earned income projections for the near-term based on scheduled activities and recent performance data

- Pledges for gifts and contracts for sponsorship

- Your plans for opening/staffing and schedules for exhibits and programming. (Subject to revision, of course, as events unfold.)

Issues that fall into the category of known knowns should be examined with the following questions:

- Is the data you have on hand timely and accurate?

- Can you collaborate with other organizations to expand and improve this information?

- How will these facts affect your strategies and decision-making?

Known Unknowns

On the other hand, there are many things you know are important, but will require new data collection/digging/analysis to provide actionable information. These are known unknowns, and right now they may comprise a very long list. For a start, it may include:

- Willingness of donors/members to contribute or renew their support in the coming year

- When the public will feel comfortable visiting museums, once restrictions are eased

- Foundations’ priorities for funding in the coming year

- Timeline for the easing/removal of government restrictions on attendance

- Timeline for rebound of domestic and international tourism

- Willingness of your employees and volunteers to get a COVID-19 vaccine

Create a system for converting items on this list to known knowns via a systematic search for existing information or by launching new data collection. During the pandemic, many critical known unknowns will remain unknown for some time: e.g., how vaccines will roll out in your community, when restrictions will be eased, and what additional financial relief may be provided by federal or state governments. Identify where this information will appear as it becomes available and monitor these sources on a regular basis.

Unknown knowns

The next category is particularly important because maps your organizational blind spots. “Unknown knowns” are critical issues which you disregard or downplay due to incorrect assumptions or false certainty. The information to accurately assess these issues probably exists, but you may be overlooking its importance. For example,

- Museums often have a great data on the age distribution of visitors, members, and donors, but assume that these categories are stable. In other words, that young people can be relied on to visit more often and donate more money as they get older. You might challenge this assumption by examining national data on trends in arts participation, or philanthropy.

- Your organization may be assuming (consciously or unconsciously) that “recovery” means rebounding to your pre-pandemic income streams. That may not be appropriate or even possible. You could have very solid trend data regarding government support—but such funding may be profoundly disrupted by the pandemic’s effect on local tax revenue and spending priorities. By critically examining potential long-term shifts in income and funding, museums can prepare to shift their business model to adapt to the post-pandemic market.

- Museums planning new buildings or significant renovations often design those facilities for present conditions and current audiences, even if the facilities are expected to be serviceable for a half century or more. Some risks associated with climate change (flood, fire, heat) may at least require fundamental adaptations in design, and may even force the museum to relocate in that time frame. By studying projections on various impacts on climate change, museums can project what needs the new building may need to fill over the course of its functional life.

As you undertake planning, root out unknown knows by identifying and questioning underlying assumptions.

Unknown Unknowns

The last category, “unknown unknowns,” is comprised of issues and events that are so unexpected they may not be covered in the normal course of planning. In futurist terms, they lie at the outer edge of the Cone of Plausibility. As the current pandemic has demonstration, it is worth devoting some time to considering improbable events that would profoundly reshape the world. Organizations can imagine and explore the consequences of potential disruptive events through so-called wildcard scenarios. For museums, unknown unknowns might include:

- A second pandemic in 2021 or 2022, arising from a significant mutation of COVID-19 or the spread of an entirely new virus. Such an event would not only prolong the current financial crisis but potentially induce long-term changes in a host of areas, including engagement with arts and culture (visitation, consumption of online content), educational infrastructure, employment, and philanthropy.

- A largescale pivot of private and foundation philanthropy away from arts and culture and towards basic human services to meet critical needs.

- Significant shifts in population if, as some have speculated, the pandemic hollows out some urban cores and redistributes workers to suburbs and smaller cities. (This trend might be driven by normalization of telework, accelerated by the erosion of the creative and cultural life of city centers due to the massive loss of small businesses and arts organizations.)

I encourage you to explore your organizational uncertainties by sharing this post with colleagues, staff, and board, inviting them to edit and expand this list to make it relevant to your organization. Mapping the limits of what you know is an essential part of creating successful strategies for uncertain times.

I look forward to exploring this and other planning tools in more depth through workshops, talks, and engagements in 2021, through conferences, webinars, and individual engagements. If you are interested in contracting me for a talk, workshop or planning assistance, please submit an inquiry to the Alliance Advisors and Speakers Bureau using this form.

Yours from the (post-pandemic) future,

Elizabeth

Elizabeth Merritt

Vice President, Strategic Foresight and

Founding Director, Center for the Future of Museums