Last week the Alliance released TrendsWatch: Navigating a Disrupted Future. The opening chapter of this year’s forecasting report addresses the need for museums to join with all sectors of society in redressing the systemic inequalities of wealth and power that have resulted from the entrenched racism that disfigures the US. Throughout the coming year this blog will feature stories of museums engaging in reparative practice, beginning with today’s guest post by Bill Martin, Director of the Valentine Museum in Richmond, VA.

Download your free copy of TrendsWatch to explore how museums can use their assets to build equity within their institutions and in their communities, and follow the work of AAM’s Facing Change initiative advancing museum board diversity and inclusion.

–Elizabeth Merritt, VP Strategic Foresight and Founding Director, Center for the Future of Museums, American Alliance of Museums

At a time when agreement is in short supply, I think we can all agree we are living in historic times. As museum professionals and leaders, how can we help the communities we serve face a challenging present and an uncertain future? How can we use our collections, exhibitions, and programs to address the modern-day impact of the history we share? Here at the Valentine, we are endeavoring to use all the tools in our curatorial and programmatic toolbox address public concerns about racial inequality while confronting our own institution’s history.

And it begins with a café.

I’ve served as the director of the Valentine Museum in Richmond, Virginia, for over 25 years. The Valentine is one of the oldest museums in the city – we opened our doors in 1898. This small, non-profit museum is committed to collecting, preserving and interpreting Richmond stories, using our past to inform the present and shape the future.

In recent years in Richmond, that past has come into even sharper relief. As the former capital of the Confederacy and the home of Monument Avenue, which until recently was lined with monumental examples of Lost Cause iconography, our city has been at the center of a nationwide reevaluation of our history – both the aspects we have chosen to remember and those stories we have chosen to forget.

The questions on my mind and the questions on the minds of museum directors across the country were undoubtedly the same: what is our role? Dedicated as we are educating the public and confronting the uncomfortable, how can a museum do the most good when responding to a movement calling on institutions like ours to reconsider and reimagine our work?

At the Valentine, we took time to do just that, albeit in our own way: we reconsidered the relationship between the museum and our restaurant space, rethought upcoming exhibitions, and began to reimagine the Valentine Sculpture Studio, another space central to our museum since its founding.

Nestled on the museum campus in the Valentine Garden is a small building used by a variety of food vendors over the years. Vacant for nearly a year, our senior staff decided the museum could use the space as an actionable, concrete response to the ongoing concerns about race-based wealth inequity, while also forming meaningful relationships with minority-led organizations.

Thus began The Main Course: A Valentine Museum Restaurant Competition. Partnering with the Metropolitan Business League (an organization that supports small, women and minority-owned businesses across the Richmond region), the Richmond Black Restaurant Experience and Hatch Kitchen RVA, we sponsored a competition for local, minority-owned restaurants, food trucks and caterers. The grand prize would be two years of free rent in the café, memberships to the partnering organizations, and preferred vendor status with the Valentine.

Following collaborative press outreach, a coordinated social media push, community input, and one afternoon of tasting conducted by a lucky panel of judges, the winner was announced on December 14. The Valentine will now begin working with Brandi Brown, owner of Ms. Bee’s Juice Bar, a local business specializing in juices and smoothies, for a grand opening in the café space in the spring of 2021.

The Main Course Competition was unique to the Valentine’s specific situation, but the lesson is applicable across museums and culture institutions. Thinking outside the box, we were able to use a traditional space in a non-traditional way, adapting our available resources as a small history museum to support a Black-owned business.

We have applied this same approach to exhibitions. The windows of the Wickham House, the historic home on our campus where enslaved people once lived and worked, now hosts an external exhibition focused on powerful images of Black hair. Curated by local artist and academic Dr. Chaz Antoine Barracks, DONT TOUCH MY HAIR rva fills windows up and down the museum block with oversized images that explore diverse African American experiences through stories of Black hair.

At the same time as we celebrate our present, we are working on bold new ways to contribute to our community’s understanding of our past.

Right across the walkway from where Ms. Bee’s Juice Bar will reside stands another space ripe for reimagining: Edward Valentine’s Sculpture Studio.

Edward Valentine was one of the museum’s founders and as a working sculptor played a central role in creating Lost Cause iconography – the same kind of iconography that remains a focal point of ongoing protests and calls for racial equity. We determined that in order to explore both the legacy of the Lost Cause as well as our institution’s complicity in its growth, the studio must be completely reinterpreted and reimagined.

Working with a committee of historians, activists and local leaders and through a series of community focus groups, this major project will provide visitors a space to confront and reckon with the painful history of Richmond’s and the Valentine’s early role in the development and spread of the Lost Cause myth.

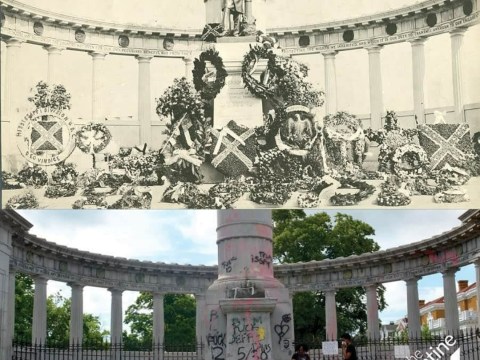

One of Valentine’s works, a statue of Confederate President Jefferson Davis, had stood on Richmond’s Monument Avenue since 1907 before protestors pulled it from its pedestal earlier this year. We are seeking to acquire the statue from the City of Richmond for eventual display in this newly renovated space, covered in pink paint and damaged from recent protests. In his current form, the Davis statue now tells both the story of Jim Crow intimidation in the 20th century and the story of public outcry against those same forces in 2020.

Taken together, the restaurant competition, exterior exhibition, ongoing studio project, and other efforts reflect the Valentine’s commitment to responding not only to community needs, but listening to community voices. Not only reconsidering our approach, but being willing to change our approach in order to better serve the city we call home.

During a time when success is measured by an ability to adapt, we hope that our work, and the work of our fellow museums, reflects the enormity, and possibility, of this moment.

Skip over related stories to continue reading article

Comments