Can the visual arts foster empathy and understanding? From our experiences as art museum educators, we believe they can, but there is little empirical research to support this theory. So, in 2017, the Minneapolis Institute of Art (Mia), with the generous funding of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, established the Center for Empathy and the Visual Arts (CEVA). In partnership with UC Berkeley’s Social Interaction Laboratory and the University of Minnesota, we are leading initiatives to develop, research, and share strategies for cultivating empathy in art museums.

Empathy is a complex concept, and even the experts disagree on how to define it, as it has many types and aspects. At Mia, we use the definition written by Empathy Museum founder and author Roman Kznaric: “The ability to step into the shoes of another person, aiming to understand their feelings and perspectives, and to use that understanding to guide their actions.” While numerous studies link this ability to positive societal outcomes—like reduced prejudice, decreased inequality, and improved health—others show it is on the decline in our increasingly divided and disconnected world.

Art can be a powerful tool for reversing this trend. In fact, though today the term empathy applies to many contexts, it was first born out of the visual arts. It originated in the German word Einfühlung (literally “feeling into”), which the aesthetic philosopher Robert Vischer coined in 1873 to describe the projection of human feeling into an inanimate object, such as a work of art. Another philosopher, Theodor Lipps, then adapted the concept to explain how we understand the feelings and experiences of another person by putting ourselves in their place. Lipps postulated that the meaning of art arises not from the object itself, but through the process of the viewer projecting themselves into the object (an “inner imitation”). In other words, he believed we appreciate an object because we understand it as an analogy to another human being.

As Stanford psychology professor and empathy researcher Dr. Jamil Zaki states, the arts “provide you with a very low risk way of entering worlds and lives and minds that are far from what you would normally experience.” By engaging emotionally and cognitively with works of art, we can develop skills that deepen our understanding of other people, past and present.

| Types of Empathy:

Affective empathy or mimicry (mirror neurons) is when we wince or laugh because we see someone else doing this. Emotional empathy is when we understand another’s emotions through facial expression and body language. Cognitive empathy, or perspective-taking, is when we put ourselves in another’s situation and attempt to feel and think about things from their point of view. Compassion is empathy in action. Driven by cognitive and affective empathy, compassionate empathy is the ability to feel and show appropriate concern in response to another’s needs and be moved to help in some way. This construct can be a motivational basis for taking action to help others. |

Recognizing this power of art, at Mia we have been experimenting with “empathy interventions” in the development of programs, tours, and exhibitions. We are working to weave empathy into our processes, through practices like community listening sessions and advisory groups, then study how empathy manifests for visitors in our galleries. In the process, we are valuing and welcoming diverse perspectives, recognizing that our staff does not always represent our communities. We are constantly learning through different projects, but it is essential for us to incorporate diverse viewpoints, cultural expertise, and lived experiences into our development process.

We have been encouraged to lean into this work by findings from our ongoing research and evaluation efforts. From studies, we’ve learned that Mia’s audience—both regular visitors and those we are just getting to know—is eager to be challenged. For instance, in a recent survey conducted via email by Wilkening Consulting, we learned that our visitors are not only curious about what they already know and like, but are more likely than visitors to other art museums to say they enjoy the experience of letting that curiosity lead to new questions and connections. Through multiple other surveys, including one of residents in our neighborhood conducted via mail by Wilder Research, we’ve also learned that they are seeking exhibitions by and for people of color, queer people, and local artists.

With this encouragement, we’ve set out on our foundational CEVA research, beginning with exhibitions that feature collaborations rooted in the exchange of multiple points of view between curators, artists, and/or members of relevant community groups. These partnerships have yielded interpretive materials, including audio and video recordings of personal stories or reactions to specific works of art, art installations, contextual materials, and programming. In addition to our regular post-visit exhibition survey about visitors’ overall experience, we added questions to address the overarching elements of empathetic thinking and feeling: emotional responses, connections with personal identity, and perspective-taking. Below we describe our efforts to measure visitors’ responses within three different exhibitions.

Study 1: EMOTION: Art & Healing: In the Moment

What emotions do people experience in exhibitions designed to promote empathy?

We began studying emotional responses to artwork in a systematic way with Art & Healing: In the Moment, an exhibition featuring artwork created in response to the deadly police shooting of thirty-two-year-old Philando Castile, developed in collaboration with his mother Valerie and a community advisory committee. On one wall of the gallery, visitors could contribute their thoughts by responding to prompts on small cards on the response wall. One of the prompts was specifically about emotion: “In this moment, I feel…” Mia team members entered all 675 post-its and began to organize them into the following categories:

| Code | Examples |

| Negative (318) Anger, Sadness, Shame, Guilt, Frustration, Despair, Weariness, Overwhelmed, Numbness, Shock, Annoyance, Fear | Filled with outrage that begs for creative, positive channeling.

Angry. You should be too. |

| Positive (155) Hope, Happiness, Love, Kindness, Empathy, Inspiration, Empowerment, Safety, Pride | Empowered to speak out with love for what is JUST |

| Mixed: positive and negative (162) | Sadness – and shame as a white woman. But hope, too. What a beautiful way to pay tribute to a son, a brother, a friend. What a gracious way to share anger. What a loving way to challenge/change hearts. |

| Expressed gratitude (48) Grateful to Mia / Valerie Castile / the exhibit | Grateful to Ms. Castile for sharing these works with us. <3 |

Through this experiment, we recognized just how little one can infer from a short response. Yes, visitors were sharing their emotional reactions, but was that leading them to empathize? We realized we would need to understand more about how identity, relationships, and connections inform empathetic feeling and thinking.

Study 2: IDENTITY & CONNECTION: Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists

Through what aspects of their own identities do visitors find connection with and empathy for Native American female artists?

Almost a year later, we had the opportunity to take a deep dive into this question with the exhibition Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists. Organized by Mia in collaboration with an advisory board of Native artists and scholars from across the United States, this was the first major exhibition of art by Native American women. In the galleries, video and audio interviews recorded in the artists’ studios and homelands appeared alongside the art, infusing the space with their stories and presence.

One of the key questions our Native advisory board wanted us to answer was, “Do Native visitors feel that the exhibition represents Native cultures in an honorable and respectful way?” Our survey results revealed that 89.5 percent of Native visitors and 90 percent of non-Native visitors responded, “Yes, definitely.” In an open-ended response field, many non-Native visitors said they felt it was not their place to say whether a culture that was not their own was represented respectfully, which suggests they held an awareness of positionality, power, and intercultural respect.

Even though the Native American female experience was the focus of the exhibition, non-Native visitors connected and empathized with the artists through other facets of their identities. In our interviews with forty-nine non-Native visitors about their experience, many said they saw parts of their identities in the artists, most notably those of mother, artist/maker, or member of another historically marginalized group. In interviews with Native visitors (n=10), many said they were proud of how the artists represented resilience, interconnectedness, and making connections between the past and present. Making connections with others across difference and understanding one’s own positionality is a key step towards empathy.

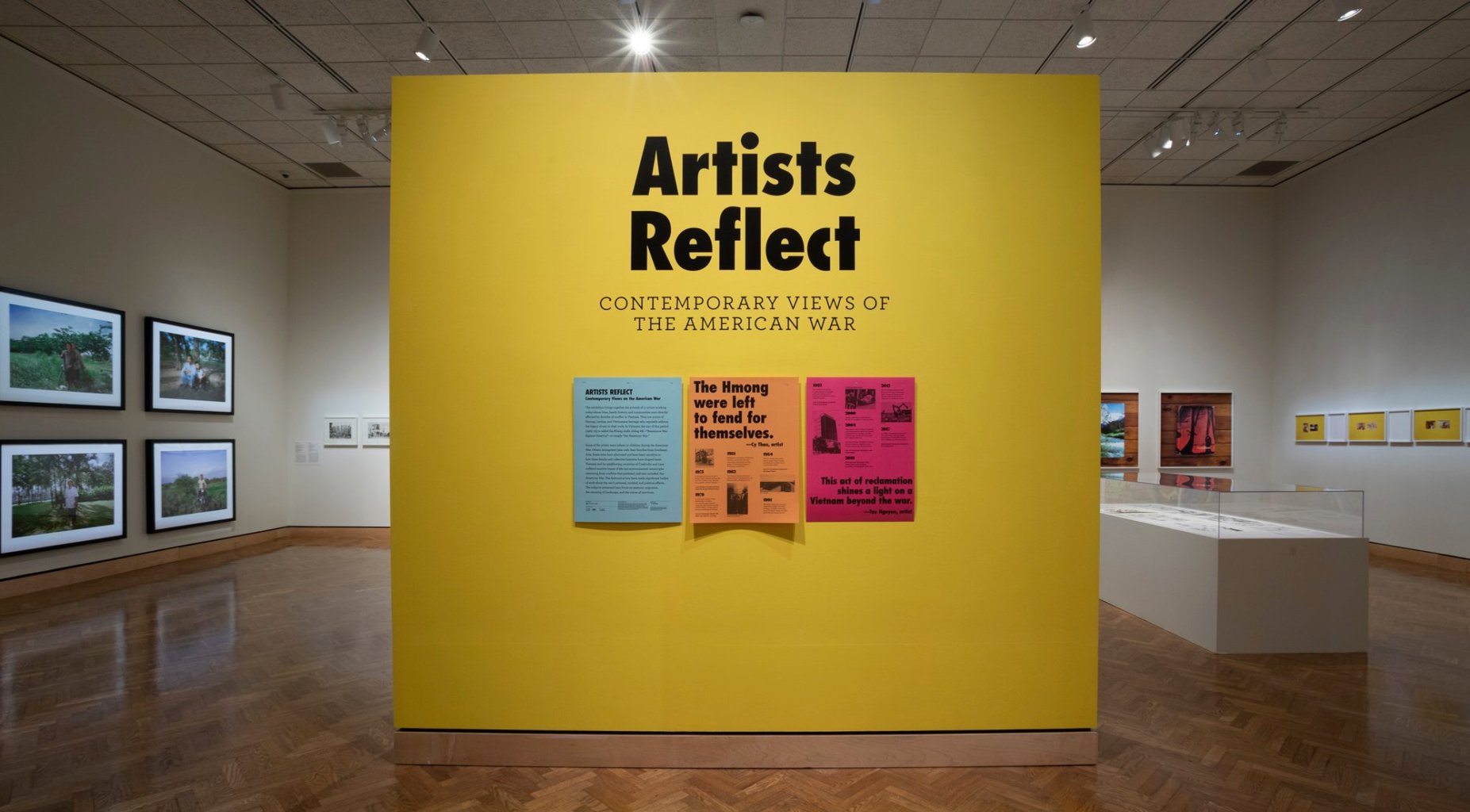

Study 3: PERSPECTIVE-TAKING: Artists Respond: American Art and the Vietnam War, 1965-1975 and Artists Reflect: Contemporary Views on the American War

How can we practice empathy in the curatorial process to prompt perspective-taking through exhibitions?

Organized by the Smithsonian Museum of American Art, Artists Respond: Art and the American War featured artwork by American artists reflecting their experiences in and reactions to the Vietnam War. Because of the large community of Southeast Asian refugees from the war in the Twin Cities, Mia decided to capture those experiences in a companion exhibition, Artists Reflect: Contemporary Views on the American War.

We wanted to know if these exhibitions, with the range of different experiences they captured, encouraged visitors to practice perspective-taking. In a post-visit survey, we asked, “During this exhibit, how often did you think about a perspective other than your own? (e.g., the artist, a figure in the artwork, someone affected by the war).” Of the 1148 respondents, 73 percent said they often thought about a perspective other than their own. The breakdown was not significantly different for people who reported a personal connection to the themes (i.e., a family member is a veteran, their family left Southeast Asia after the war, they were a young adult growing up in the 1960s, etc.) versus those who reported none. This suggests that the exhibition worked similarly well for engaging visitors who already had a connection to the war as for those who did not.

What’s Next?

Through our continued CEVA research, we learn, iterate, and integrate new findings into our practice. Through our studies thus far, we know our visitors and collaborators…

- Are creative, curious, and seeking experiences that open them up to new ideas and perspectives.

- Deeply appreciate and welcome contributions from artists and people with relevant life experiences.

- Will need multiple and ongoing experiences to deepen their empathy practice and ultimately compassion (empathy in action). True empathy—feeling with another person and looking at things from their perspective, not our own—will likely need nurturing beyond what a single visit to an exhibition can bring.

Although COVID-19 has interrupted our work with visitors, we are collaborating and planning for the future. Currently, we are developing the interpretation and research questions for Supernatural America: The Paranormal in American Art with a focus on historical empathy and perspective-taking. For this exhibition, we are working with representatives of various faiths and spiritual practices who are helping us think broadly and sensitively about belief systems, the supernatural, and rituals of loss. We are also experimenting with interpretation by centering essential questions, which we will pose to visitors in the exhibition.

We are committed to sharing our learnings and findings with the field, so look for future writings and presentations.

Learn more about our work: https://new.artsmia.org/empathy