After of year of chaos, anguish, and reflection, the world is entering a new phase—perhaps “post-pandemic,” maybe the “new normal”—it will take a while to settle on the right label. Last year, the AAM Committee on Audience Research and Evaluation (CARE) created the Essential Evaluators blog series to reflect on evaluation in relation to the museum field and larger societal stories during COVID and a year of racial and social justice upheaval. And although that immediacy has faded a bit, the importance of evaluation to the field has not. In this vein, we are saying farewell to the series. I want to thank my co-curators along the way—Rose Jones, PhD, and Andréa Giron Mathern, PhD—and all the contributors and readers. CARE will continue to post great examples of how evaluators are working to provide answers and confronting ingrained ideas linked to systemic racism and bias, but each post will relate to other stories from the field. For our first, post-Essential-Evaluators-new-normal blog, we bring you a study that will certainly pique the interest of many—what do parents want museums to provide their children in relation to virtual programming?—read on to find out what Rockman et al. found!

—Laureen Trainer, Trainer Evaluation & CARE Board Member

Many museums have turned to audience research and evaluation over the past year to make decisions about opening status and planning for programming and exhibits. However, most of their studies have focused on health and safety concerns for returning (e.g., mask-wearing, social distancing, capacity levels, etc.), and less on public preferences for alternative programming like remote or virtual learning activities. As researchers, we saw a gap there, since even as their online offerings have proliferated during the pandemic, museums are still wrestling with how much (or whether) to continue to invest in virtual programming given the considerable time and effort it takes to design and produce these programs. Given this conundrum, we wanted to learn how museums, children’s museums in particular, could better design or plan for virtual programs that best aligned with audience needs and interests.

Last fall, we reached out to Carol Tang, CEO at the Children’s Creativity Museum in San Francisco, about conducting a pro bono survey amongst Bay Area children’s museums to collect parent/caregiver feedback on what they would like to see in virtual programs for their children. With Carol’s help, we were able to expand this opportunity to thirteen other museums across the country through the Association for Children’s Museums’ (ACM) network. A range of museums participated in the study, spanning from larger urban-based institutions (e.g., Chicago Children Museum and Minnesota Children’s Museum) to those located in smaller rural and suburban areas (e.g., Children’s Museum of Saratoga and Children’s Museum of Sonoma County). The museums came largely from the Midwest and West Coast, but all major geographic regions of the country were represented to some degree.

The study consisted of a simple survey sent to the museums’ members and mailing lists. We developed the survey items in collaboration with a small number of participating museums. After many months of varying degrees of lockdown and museum closures, we wanted to understand what types of virtual programming parents want now from children’s museums. We were also interested in how virtual program preferences might be influenced by a child’s school or care situation, the child’s age, and the amount of screen time they get each day.

Between November 2020 and January 2021, we gathered over twelve hundred responses from museum members/and or visitors. The bulk of respondents were parents or caregivers of children ages two to seven participating in a variety of school and care situations: in-person, virtual/remote, hybrid (both in-person and remote), or homeschool/home care.

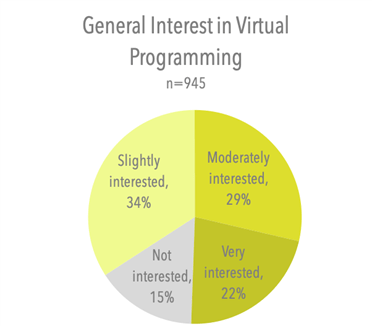

Our findings show that parent interest in virtual programs is divided. About half our respondents said they had “no interest” or “slight interest” in virtual programs, while the other half expressed “moderate” or “high” interest. One overriding concern for participants regarding virtual programming was the amount of screen time that their children are already experiencing. One in five participants reported their child spending more than three hours on a computer or digital device each day. In addition to screen time concerns, some parents were worried that their children were too young or might not have the attention span to concentrate on virtual programs. Others weren’t sure whether they themselves had the capacity to manage the scheduling of both in-class and virtual activities for their family.

We were surprised to find, however, that more screen time did not coincide with less interest in virtual programs. It appears that everyone’s threshold for Zoom fatigue is different. The fact that 85 percent of respondents expressed some degree of interest in virtual programming should offer museums some optimism when considering investing in it as a core institutional activity, as should the fact that almost 60 percent indicated willingness to pay for it.

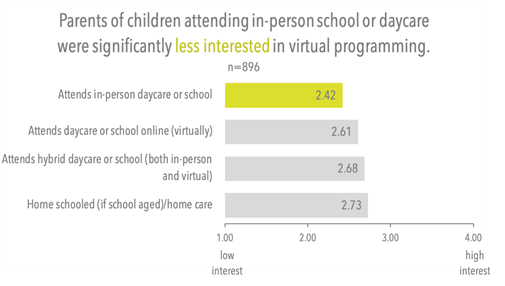

Parent interest in virtual programs was linked to the type of schooling or care their child is currently receiving. We found that parents of children who are attending school or daycare in-person had lower interest in virtual programs than those whose children were homeschooled, attending school online, or attending in a hybrid situation.

We were also interested to find that respondents’ interest in virtual programming did not vary depending on the age of their children. This finding might not surprise all children’s museums, though—we recently learned that Habitot Children’s Museum in Berkeley, California, has been holding “sippy cup social time” on Zoom for their youngest audiences!

Despite some of the concerns raised in parents’ open-ended responses, it’s also clear that many are craving a way to reconnect with their local children’s museum during the pandemic and somehow replicate the experience in a home or remote environment. This indicates that when considering virtual programming, children’s museums should play to their strengths. Parents showed an interest in programs that offer the kinds of experiential learning children’s museums excel at—those that actively engage participants versus more passive activities, those that provide socialization opportunities (e.g., cooperative activities that encourage sharing, communication, and negotiation with peers and family members), those that enhance creative and critical thinking skills, those that provide kinesthetically oriented experiences (e.g., hands-on science experiments or dance and movement classes), and those that promote independent learning while also furnishing time for parents to learn alongside their children. On the other hand, parents clearly did not want activities that replicated what children may already be getting from their virtual school lessons, such as read-alouds or programs focused on study skills.

These are just a few of our findings. We hope you will check out the full report on our website. We are grateful to have had the opportunity to investigate this important topic and provide some quick feedback to museums as they seek to make decisions on how or whether to invest in virtual programming going forward. And while this survey focused on children’s museum audiences, there are important lessons here for all museums considering investments in virtual programming. Audiences miss their museums and the special experiences they offer. If visitors are going to spend more time on a screen, museums will have to make their programs stand apart from the other ways we spend time online. We are aware that as the pandemic situation changes around us (museums and schools reopening, continued fears about health and safety, etc.), the needs and desires of museum audiences will change as well.

This survey provided insights into the minds of audiences over the fall and winter of 2020, but what may change in the future as more schools and museums reopen or perhaps face closure again? Will audiences tire of virtual programs, or has the genie been let out the bottle and remote learning become a mainstay of education and the driver of a visitor’s more blended relationship with museums? Can museums use virtual programs to extend their reach to the underserved audiences, increase access to diverse communities, or add value to their institutions as trusted sources of information and learning? Where could collaboration between museums or between museums and school districts strengthen both the informal and formal education landscape? What role can researchers and evaluators play in facilitating this discussion? These are just a few of the questions we hope to explore in future studies.

For more information, contact, Scott Burg: scott@rockman.com or Claire Quimby: claire@rockman.com