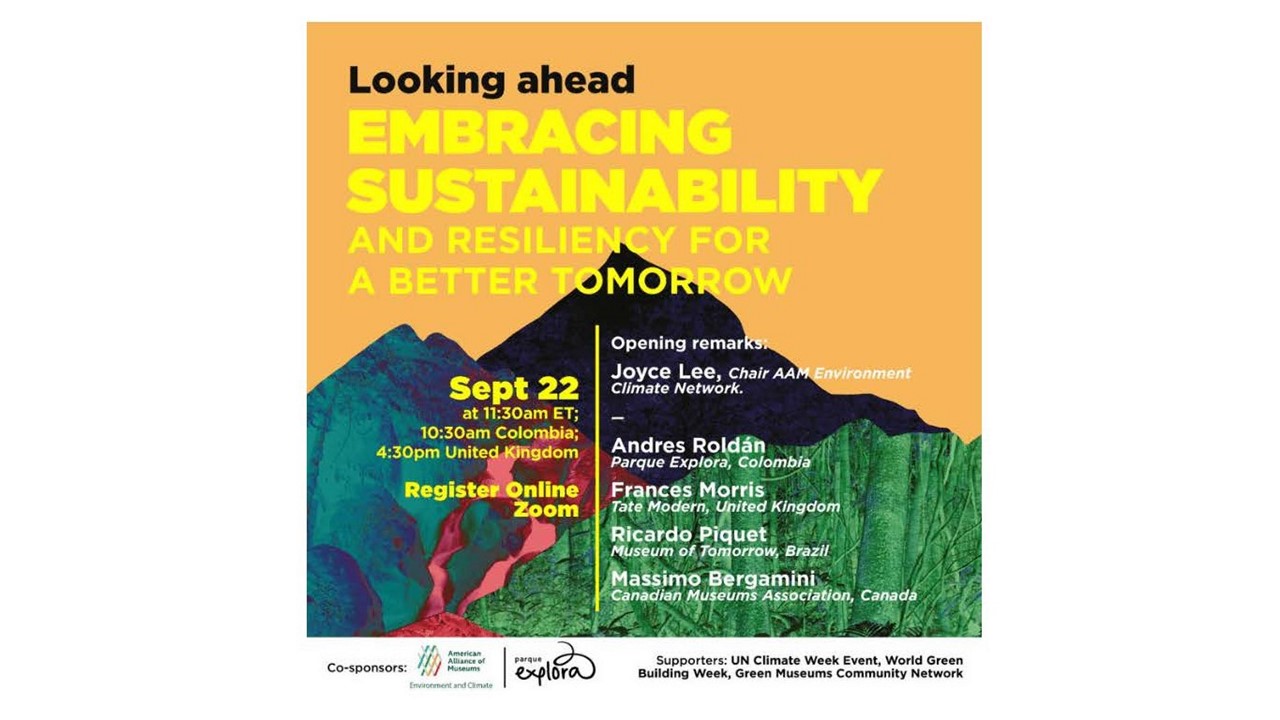

The United Nations (UN) Climate Week provides a platform for organizations which include museums and cultural institutions to come together to discuss how an understanding on environmental sustainability and climate action can be advanced through education, engagement, and collaboration. This webinar hosted by Parque Explora in partnership with the American Alliance of Museums (AAM) Environment Climate Network (ECN) invited distinguished museum directors from different continents to engage in an insightful dialogue addressing their response to operational sustainability while preserving cultural heritage and inspiring, protecting and respecting their communities.

Transcript

Joyce Lee: Good morning, good afternoon, and good evening. I am Joyce Lee, the Chair of the Environment Climate Network at the American Alliance Museum. AAM is the largest museum organization in the U.S. Our network is dedicated to advancing sustainability goals within the membership. We also helped AAM sign on to the Climate Heritage Network. Stay tuned for our Arctic Museum Virtual Event in early November, when COP 26 is happening in Glasgow, UK. When I served in the Bloomberg administration in New York City, we remember this international UN Week as full of traffic congestion every year because of all the heads of state were in town. Now COVID-19 has been thinning the traffic a little bit. And with flooding of the New York City subway only a few weeks ago, our conversation had decidedly taken a climate turn. Our contribution here is bringing a cultural angle to expand the conversation while holding the sector responsible to do its part for meeting the climate, Build Back Better goals. To quote the CEO of the World Green Building Council, Christina Gamboa, originally from Colombia and now based in London, UK.

She said museums offer many social, cultural, and scientific benefits for our society. As the epitome of learning and ingenuity, it seems only right that these buildings should also be making the transition to a net-zero future. By ensuring that museums provide positive benefits for climate action, we can make sure that cultural assets can continue to be an important symbol of sustainable innovation. Thank you, Christina. So why are we having a museum leadership conversation today? Because museums are pillars of the community. They are socially responsible, and they are educational institutions. Artists, historians, and scientists can communicate effectively about climate, and museum leadership can also empower. Some museums have even completed the scope one, two, and three assessments, while others are just learning the sustainability language. In 2019 before COVID, our firm and AAM did a calculation of the museum sector, emitting 12 million metric tons of carbon every year, and just in U.S. alone which has the most museums of any country. As we heard from Monday’s keynote on the climate tipping point for humanity, we must act now and with urgency and commitment. Are you targeting net-zero?

With this panel of thought leaders that are assembled today, we are grateful to have a second year of serious discussion. Last year AAM partnered with Asia Pacific Partners and museums to discuss the sustainable development goals, SDGs. Today we are tackling climate and cultural resiliency, to better prepare for the challenges of tomorrow. This year our network partners with a Latin American institution, Parque Explora. That also has a long history with AAM. Our planning took place during a time when many museums in this country and in Latin America are facing challenges. But Andres was the eternal optimist. Therefore it’s my utmost pleasure to introduce Andres Roldan, the Director, and CEO of the Parque Explora in Medellin, Colombia. I would also like to thank our network colleagues, Christina Dillard, Andrea Frey, and Chris Hopps in this event. So Happy UN Climate Week in New York City and Happy World Green Building Week. You have made contributions by simply tuning in today, and there is nothing better than museums walking the talk. Thank you.

Andres Roldan: Thank you Joyce for the introduction and welcome everyone to this session. Right now I am in Medellin, [crosstalk 00:04:37]. Today is a kind of great day. Climate here in Colombia, it’s usually kind of messy. Some days are sunny, some others are rainy. And sometimes it’s becoming more sunny and more rainy every single year. And I guess every spot in the planet is facing different ways of having evidences of how climate is changing and how our societies are moving in different directions that in a way puts museums and institutions to think about what is the role and how to embrace new cultural sustainable practices, and at the same time how these practices are influencing the vision of different institutions. So, the idea of this session that we’re going to have to today. It’s to have different perspectives of places in the world that in a way are facing this conversation from a different point of view. In a way, I guess that climate change isn’t any more like another layer of action but it is becoming increasingly a part of the mission.

How institutions are reframing their cultural, their objectives and the way how they measure their own value in the environment day-to-day [crosstalk 00:06:08]. So one of the thing that we will to do-[inaudible 00:06:18] people can just put off all the voices that will be very helpful for everyone. So, just to start a conversation we are going to have a first moment where we are going to have an introduction by two leader of museum field. We’re going to have Frances Morris, Head of the Tate Modern in UK. A contemporary and modern art museum that it’s a landmark on the field of art and I guess now even on climate, and we’re going to hear some of what they are doing. And we are going to speak with Leonardo Menezes. Leonardo Menezes is joining us instead of Ricardo Piquet. Ricardo Piquet has a last-minute personal situation that couldn’t allow him to be participants. But Leonardo is also a leader that it’s been since the foundation of the Museum of Tomorrow in Rio de Janeiro in Brazil. He’s a curator and he’s been working on the field of museums since a long time. And the idea of this session is that we are going to have an open conversation on climate change from the perspective of our institutions.

And at the end, we are going to have Massimo Bergamini, who is the representative of the Canadian Association of Museums. Where we want to round up all the ideas that we’ve been putting on the stockpot in this conversation. His experience of transforming into policies that move forward the field, it’s key for the role of the museums and how we are reframing our own definitions as institutions. So let me start this conversation, giving the word to Frances and to know a little bit how the museum is changing. What is the perspective in the last couple of years of the Tate Modern around the climate change and how this is changing your own perspective as an institution? Frances? You are off. Okay.

Frances Morris: Unmute me.

Andres Roldan: Yep.

Frances Morris: Am unmuted?

Andres Roldan: No. You are okay.

Frances Morris: Good, okay. So first of all it’s a great pleasure to be here today with colleagues from different parts of the world. I think all of us tend to exist in our own little silos. Whether the city in which we operate, the nation-state, or a bit of the sector. So to speak to colleagues from outside the fine arts sector and from outside Western Europe is incredibly important to me at this moment because of course climate is a truly transnational issue. I want to speak a little bit about Tate Modern’s own journey. I’m mean I’m sure most of you know Tate Modern but we’re part of a federation of museums, The Tate Galleries. Tate Modern is in central London. It’s both a local, a national, and an international museum. And by national I mean it’s part-funded by our government. So we have an agenda that is governmental, which is important and restrictive. We have had a long history of commitment to sustainability, and it’s very difficult to change the course of a ship once it’s moving.

But in the early part of this century, we committed to a new building on the site of Tate Modern. And in 2007, committed that set out to create what would be a new benchmark for sustainable museum building. And at that quite early stage for the sector, we work towards a target of 40% less energy, and 35% less carbon that now demanded by existing building regulations in the UK. And for 10 years following that decision, amazingly enlightened and committed colleagues who run our buildings and our states, have done an amazing job very quietly and under the radar and without publicizing it, done a huge amount to create momentum and to change a kind of behaviors so that we are now well on the way to achieving a 50% reduction in carbon emissions by 2023, from a baseline and 2007-8. And we’re very much working towards net-zero by 2030. But I’m on the curatorial side, and it has always for the last 20 years been business as usual, the growth model, more numbers, more exhibitions, more income, more international travel, more acquisitions, explode the canon, celebrate overlooked artists, etc, etc.

Until 2019, when a group of artists from across the UK came to Tate and they asked for a meeting, and they sat down round the table and they asked me and my colleagues if we would declare a climate emergency and join them? Particularly activist groups like Culture Declares, in coming out and making a commitment that would not just be a verbal commitment but that actions would follow. And because we are a museum of contemporary art and our constituency is the artists as well as our community in our neighborhoods, and because art is at our core we felt duty-bound to undertake that commitment. And I have to say the impact has been completely extraordinary. So it was a pledge to make those kind of obvious tangible actions around carbon emissions, go green in terms of electricity, reduce our travel. But be much more fundamentally it was about examining, beginning to examine our values, our systems, our programs to become more adaptive, to become more responsible, to show some sector leadership here, recognizing of course that museums as public spaces our fate is inextricably bound up in the fate of the planet.

And sustainability cannot simply be about our sustainability, it’s about our sustainability of our ecology, of our sector but beyond that to the place we occupy in the world. So what has been really I think fascinating and important for me is how we’ve dug deep into our content, and we’ve created a kind of moments where we look at art with a kind of eco-critical eye vision so that art history isn’t just about form but it’s also about the way artists tell the histories of our planet and our people. We’ve given space and place to making clear and bold messages about climate emergency, and in particular about the intersection of climate with social justice. Because of course as a public institution, we must simultaneously address the intersections of people and planet in those areas of social justice. Because we’re of course as an ambitious institution who value art and quality, we’re equally committed to equality. So, that recognition in a public space has to quote Joyce, really forced us to be very self-reflective in quite a tough way, to acknowledge the contradictions of our organization and our place in the world.

But to really try and move on from talking the talk to walking the talk. And of course the huge challenges there for all of us institutions, particularly institutions that purport to have a global reach and responsibility. And I’m really looking forward to the conversation with colleagues and with members of the audience this afternoon, to see where the synergies are and where we can work together more closely and more powerfully in collaboration.

Andres Roldan: Great and interesting how the voice of the museum came up even from the artistic community. That’s important because sometimes, we the institutions are framed by our stakeholders but in a way resiliency in these times means also how the museums are open up not only to speak but to listen and to create visions about that. So now, Leonardo I am aware that you’ve been since the foundation of the Museum of Tomorrow. And how such an institution could be think in the beginning what was the the driver of having such an amazing project to be set up. Because I guess one of the most complex things in our planet today is to think precisely in the future. This is the time of uncertainty and to define the spot in the future which is at the end the future of life. It’s a big challenge so tell us a little bit about the story of the museum and how are you engaging to that.

Leonardo Menezes: Thank you Andres. Thank you Frances. It is also a pleasure to be here. In the place of Ricardo Piquet, our president of the museum. And I have the honor to have been since the beginning of the curatorial side of creating the Museum of Tomorrow, supporting Luis Alberto Oliveira who was the curator, the founder curator of the museum. Of imagining a museum that could captivate the invitation for visitors to imagine a sustainable world. So the Museum of Tomorrow is not about technology, it’s about a humanistic point of view of how can we figure out the challenges for the next 50 years, funded by and guided by some of fundamental questions that we invite our visitors not only to answer but to think about new questions that drive from it. So where do we come from, who we are, where are we, where are we heading to and how do we want to go? And the museum asks those questions based on the pillars of sustainability and conviviality. That means that we ask a fundamental question of, how do you want to live among ourselves and with the planet for the next 50 years to come?

In that sense we invite different communities. Communities that are over there with us in the place that we are, in the harbor region of Rio de Janeiro, is the oldest part of the city and also a black community residency that we invited first to visit the museum, and that we have programs for them to visit the museum for free every day of the year. And we try to build up opportunities with them. So we invite not only them but also the almost five million visitors that have come across the doors of the museum in this past five years there we have been open. In the sense we invite our visitors to think how tomorrow actually is today, and that today is the place for action. Because since tomorrow is so close to us, how can we think that our everyday choices reconfigured tomorrow every day. In that sense, we are also a museum that it’s a beginner’s dose for the world of museums since almost, around actually 20% of our audience is the first time they visit a museum, is when they visit the Museum of Tomorrow.

And that says we have a really big responsibility of showing the world of museums and how we can lead the talk about how sustainability can shape a new society based on the pillars of plurality diversity because those are the pillars that biodiversity has made his way through resilience, through several millions and billions of years of change. In this sense we are also aligned with the UN 2030 agenda for Sustainable Developments, the Sustainable Development Goals. They are the guides that we envision our programming but also physically the Museum of Tomorrow is carbon neutral since its opening. So we have been doing net zero emissions since the opening of the museum. And we not only do that through our projects and we paid also for that but also the building itself we use the Guanabara Bay water which we are right above it in our cooling system. We have solar panels that really help with the use of electricity that we have on the building.

We are doing our correct packing waste disposal and recycling policies but let’s face it I think that every museum should try to address those issues such as state modern too is already doing but also try to really put and mark the way of how can we be lighthouses that will signal the way for other institutions to come and follow the way for sustainability. In our programming all the exhibition, temporary exhibitions that we have put up since the beginning of the museum, the ones that were produced by the crew of the museum. They always addressed the topic of climate change. Whether its exhibition about innovations in Brazil whether it’s about the food production for tomorrow, whether it’s about the pandemic or about the Amazon exhibition that we are producing for the end of this year. Climate change is perhaps the biggest change that we will face as a human society in our planets for this century and therefore we must show that we are in a special time. A special time that we already know information enough.

And I think the IPCC panel has been really clever on how to address those issues for the audience. But us as a museum we must create experiences that try to not only activate the rational features of our audience but also the emotional features. Because to really try to change habits and to change lifestyles towards a more sustainable livelihoods. Where we must also make people think about how can they change their daily lives and we are going to do that of course through information and of course also through arts. Because that’s the way that we can really try to give a vision of how long term and how our collective actions must unite in terms for us to address a more healthy planet, a more healthy biodiversity and of course our role in this sector. And us, as a museum, we have the trust of our audience and we should inspire them and move forward. Thank you and I’m really looking forward for the conversation to continue.

Andres Roldan: Okay. I was mute, sorry. Well, I hear a word that I like very much and I guess in the core of both institutions from a different perspective there is a concern. Which is, I guess how do we reconfigure the relationships between our community, society with nature with the place where we are. And of course the history of museums has been framed for the perspectives of different times of these relationships. Natural history museums were in the core of the colonialism where the patrimony of cultural arts and nature were gathered in a gallery to describe a world that was open that was outside but in a way in the perspective of those who collected those stuff. And in a way the nature has… It used to be since I guess the illustration like a raw environment where humans were just trying to define it and to give a name. Indeed, Alexander von Humboldt was kind of the the person that in a way tried to define this concept of nature around this kind of pristine, basic thing that is around us and that we are there to explore it.

But I guess today the challenge is bigger than that and it seems that all related with environment is related with our bodies, it’s related to our neighborhoods, it’s related to our cities. The relationships with nature are defined in many ways by how we are understanding the development model of societies that we are having. And as Frances mentions the climate justice it’s different in different perspectives. The first idea that I get into here before we start up to speak about some examples of what you are doing is that there is a mind shift in the concept of the role of the museum. And the mind mind shift is not only related with culture or history or joy or emotions, but also of how to make a social transformation to make people to jump into a different level. So I guess that my third question for both of you will be, what or how do you see the, which are the best tools that you think are working for you that really works in people to change an attitude, to change a perspective.

What is your bet in the what you are doing in your exhibitions and programs that are showing you that changes are possible in our communities and societies, related to become into more sensitive and of course more committed and make that perhaps visitors become also advocates of a critical thinking of how things should be done in a different way that wasn’t as in the old days? Where do you think you are making the difference to touch the souls, the minds, the spirits of people on the experiences that are having in the museum and why you are choosing in that way? Is that clear? The question?

Frances Morris: Do you want me to kick off first?

Andres Roldan: Sorry.

Frances Morris: Do you want me to start?

Andres Roldan: Yeah, please go ahead.

Frances Morris: You’ve asked a very very complicated question. Should I start writing a book?

Andres Roldan: Yeah.

Frances Morris: I mean I suppose I would, first of all, say that, I mean firstly I loved what Leonardo said about the Museum of Tomorrow and what an extraordinary project to be able to have a kind of a blank canvas to construct it in that way. But institutions like many of those that people on this webinar work within, and certainly my own. Their roots go back to the 18th century. And their structures, their hierarchies their modus operandi, and many of the values that are deeply embedded in their kind of psyche are the same values that created the empires, the colonial voices, the industrialization and the disparities of wealth. The patriarchy that underline all the, or many of the inequalities that actually…. For which we can understand that intersection of climate and social justice. And where I see the most effective way of the museum intersecting now, is where even in small discrete and sometimes unexpected ways, it manages to somehow deconstruct those hierarchies and boundaries. And the most successful projects, and I can only really speak about the things that I’ve worked on at Tate.

The most successful projects over the last 20 years at Tate have been where, and I hate using the word ecology in a context like this because it so speaks to the kind of climate. But by ecology I mean a kind of system where you take boundaries away, and you see how things interconnect. And to take, as we have done with our collection that kind of ecological approach, and ditch the old canon of art history bound by nation states, chronologies, media hierarchies and create a, you think about it as a kind of in a present moment as a kind of what can be relevant now. Particularly to people who don’t come with the academic skills or the privileges, that when you do break those boundaries down and you do it with integrity and commitment and often with participation, you can begin to create something that is rather exciting and and feels more public, and less privileged. And I will give you just one example of a kind of ecological project that has recently taken place at Tate.

Which in itself has demonstrated that you can work against the hierarchy that exists in so many organizations between the kind of curatorial, kind of creative area and often then the people who deliver the learning or education and those others who are front of house. And this was a project where we actually worked with our research center, looking at Avant-Garde Japanese art from the 1950s, and worked with both a professor, a Canadian Professor Ming Tiampo and a contemporary artist A. Awakara, to work with curators learning… Our learning team and our front of house team, to create a participatory practice for families over the summer. Which was to scale in our turbine horse as big as anything we’ve ever done as a kind of commissioning project. But the sheer number of families and the extreme diversity of those families, so reaching a kind of communities who, the communities who don’t trust us. Because what we do isn’t for them. And I think that what was successful about that project as a kind of, as a paradigm was it just moved away from that old-fashioned museum model, of a place that tells you what is important and where you go for a passive experience.

So that that seemed to me to really begin to help me unpick how we might move forward away from the more traditional exhibitionary model that we currently have in place.

Andres Roldan: That sounds great. I don’t know if Leonardo, do you have any other concept? Because this idea of trying to take down the barriers that in a way has framed museums, and how to make that the practice of the experience as Frances has mentioned that the privilege is not for a couple but for everyone, and in a way that being in a more open and participatory environment is a way of shifting this cultural transformation. I think it’s a different perspective in Rio where most of the community it’s precisely, I guess the less privilege in many ways that’s what happens even in our own environment. So I guess that the challenge of how to create this sense of awareness is different in where you are. How is that?

Leonardo Menezes: Sure. I really think that Frances tackled the points. I think that when you really address how the diversity of our audiences can contribute to the dialogue that we want to engage, not only our visitors but our institutions. And the way that we as a society and as a museum and especially as a science museum, we have an important role of how can we really try to bring up to people these questions about, what can I do? What can us as a society also do? And I think that we as a museum, we must as a trusted institution we must not only inspire them but also to envision with them a new way of how can we decolonize some of the environmental issues that have been guiding, especially the environmental section since the last century. How can we bring other groups and societies that have not been heard in this construction of a sustainable future such as black communities, such as indigenous communities? And in this way we have to try to work not only with the visitors but also from within.

And as a museum, we have not only struggling but also trying to think about how can we try to deconstruct it from inside. And in our case in the Museum of Tomorrow, we have had a scientific committee that has guided our scientific vision since the opening of the museum. And in this year we refunded the scientific community, calling it The Scientific and Knowledge Community. Where we have also indigenous and people that are not only in the high-tech and universities of Brazil, but also from communities that people that have traditional knowledge, that is very much important for us to understand how can we live with the planets and still develop ourselves. And they have done it for centuries and even millennia. And those thoughts can inspire us as a new vision that we can show our audience different initiatives, that have been happening for a few years now that they can join. And I think that this collective sense that we must as a society be embarked in it together. I think that it really has a difference of how normally the visitors address our educations asking, “But what can I do?”

And the educators say that, “What can we do?” Because if we not as our society work together to really create this connectedness, we will not really evolve in the actions that we must really take these decades to evolve. And that’s the time that we are. And in the sense we have been really trying to present this diversity in our works that we do in our exhibitions. For example for the Amazon exhibition, we have a final video piece where we invited different people that live in the Amazon region. Scientists, teachers, people that deal with technology. Students, youngsters, mothers and indigenous and traditional workers to ask them, what is the amazon that they want for the future and how can we get there? And when you see that there is LGBTQ people, black indigenous, to show off the plurality, the social plurality that we have in the region. It gives them the sense that we as a society, we must try to co-construct together with all those groups, this vision. And I think that also the audience is changing.

The youngsters they do not only to passively see a work of art or interact with a scientific experiment, they want to co-create. And we must give them the tools to co-create with us if we want to to discuss with them and dialogue with them in this co-construction of this sustainable society that we must face forward.

Andres Roldan: Thank you. Well, I can see the word for your place like co-create and think differently for who we are serving and how the ones that we are serving have many of the answers and perspectives that we require for the museum. And I’m going to do something, well Massimo it’s going to help me to reframe many of the core ideas that we are picking up here. But I want to jump to Massimo because you lead the Canadian Association of Museums. And I can see that in Canada there’s, of course, the First Nations communities around where I’ve seen that there’s concern in how to embrace different voices, different to the traditional western museum. So just a question for Massimo if you’re with me now. How in Canada where the two worlds are colliding in all the territory, are also facing the same perspective. The one of, how to embrace and make participants the communities where we are, to be part of the narrative of the content and the mission of the museum?

Massimo Bergamini: Thank you. And thank you very much for this. Because this is so absolutely germane to the conversations that we are now having in Canada. I mean, what Frances and what Leonardo said could have been said in one of our meetings, because they speak to the same reality. The need to reinvent ourselves, to recognize that our institutions are rooted in a colonial mythology. That is still very present, that is still dominant. That we need to reinvent ourselves based on indigenous truths. And I think in this sense what Leonardo said is very important. The notion that western scientific models and paradigms can and should coexist in a respectful manner, with traditional indigenous or alternative forms of knowledge and understanding is absolutely critical. And I think is the kind of paradigm change that we need to embrace. The notion of inclusiveness is something that we struggle with, that we are absolutely focusing on as a community. Because we understand that if we are to remain relevant, not only to our audiences but to our mission and to our role. We must become reflections of our changing society.

And that is a path that is not an easy one. I can say that our government, our national government is walking on this path with us, is supporting an exercise we, as an association are developing, are working with indigenous communities to understand some of these tensions and develop tools for our museums, to better represent these realities. So I find it very rewarding to see that whether you’re in Canada or in the UK or in Brazil, that the conversation is the same and that the roots of this conversation are very much the same.

Andres Roldan: Great. Well, in the last couple of years there’s a trend of how to use culture as a way to mind shift complex concepts. In a way climate change isn’t an easy phenomenon even to be explained. And in a way that’s a problem. Well, I work in a science center. And of course to bring up the concepts of science that’s behind phenomena, it’s always a challenge. Because the language and the conditions and the phenomena are part of these problems. But in what I’ve seen is that, for example the case of the Tate where it’s not only about understanding but also to be connected or emotionally engaged. Put in the spot of creativity in a different mindset, allows a mind shift I guess. And I love what Leonardo said about this committee that is not a scientific committee but a knowledge committee. And that’s an important thing because it’s not about who are the main voices that should be saying what’s wrong or right. It’s about how the cultural frame where we are working, it’s really embracing concepts, emotions, sensitivities that in a way influence the changes.

And this is important because sometimes museums become very scientific or very aseptic on the artistic vision to be in touch in such complicated topics. But the thing is that there’s something in the middle where the performative arts, the arts itself, the narratives are tools that allows us to, and I guess that’s the role of museums. Like to use intelligent these tools as a way to make you comfortable, to embrace this content and in a way to participate into that. And I can see that Frances is raising the hand. And because I can see that there’s something in that concept that where artists says we should declare this. Which is curious, it’s a different voice. It’s not the voice of the scientific committee of whatever. It’s the voice of the artist or is the voice of those communities in the favelas or in the indigenous communities where are rising of the voice. So, I guess there is an idea there that the mission should be driven by a more collective and kind of be more influentiated by these voices and how to articulate that.

And I don’t know if you want to add on this Frances? Because I see that there’s something clicking in you. You want to add something on that?

Frances Morris: Well, just I mean I agree that I think artists are a kind of, they are themselves part of the mechanism for social reflection. And so it’s not, I don’t think it’s a surprise that artists… Even if it’s not reflected in their own work are processing, and have a sense of urgency. And they are also creative thinkers so they can think and they can imagine a future. But I think there is a real challenge to institutions, is that as we imagine a potential future that is urgent and necessary, we’re also having to deal with loss. And I’ve seen this over 20 years as we’ve rewilded modernist art, for example. We’re also grieving the loss of a set of values that we learned when we were younger about aesthetic formalism and a power and a set of values we are ditching, as we grow a new set of values. And for the last 20 years we have built that future by adding on, by adding activity, by building extra buildings, by adding exhibitions, by creating new spaces, [inaudible 00:46:40] laboratory thinking. But what we’ve never done is taken away things that existed in the past.

So we’ve exploded the cannon, the cannon still exists. We’ve done radical experimentation alongside old-fashioned ideas. But there comes a point where we have to just say, “We cannot grow any more. We now have to change.” And that is the breaking point. That is the thing that keeps me awake at night. I can add new things but how do I take away the old things?

Andres Roldan: That’s a… Well, especially when you collect this patrimony then what’s the relevant patrimony that you should keep?

Frances Morris: We can’t take everything into the future.

Andres Roldan: Yeah. And what’s the kind of new patrimony under new circumstances of what’s going on right now? Why some piece or some interaction is relevant? How to choose on that knowing so little about the future in so many ways?

Frances Morris: Yeah. I mean in a way it’s like, when we used to rehang the collection. We called it from Duck to Rabbit. There’s that great drawing. When you look at it from one angle it looks like a duck then you look at it again it looks like a rabbit. So you change everything bit by bit and, “Hey…” Suddenly it’s a different animal. And we have to do something like that with the museum.

Andres Roldan: That’s right. How, I guess that in the case of Leonardo it’s different because you are always with a blanket where you want to just get into that. But is there any interest for you also to collect that things? Or it’s all only functional to the experience of the visitors? Which is a different perspective. One thing is when you are the corridor of creativity where, things happens inside you and the other perspective which is the one of science museums and these institutions is that to design thinking in something and be very functional into that. Is that like that? Or you are also working with, you mention art and so on. But how this is frame and how are you doing that? That is not only through artists but perhaps through the message where you want to work? I allowed you.

Leonardo Menezes: Okay. There you go. Yes, thanks Andres. I think that we are mostly a digital museum, of course that we are in a building but we use the digital technologies to enhance our visitor experience. And I think that besides from the long-term exhibition that we actually update and that’s how we try to keep it somewhat relevant. Since the opening of the museum five years ago we have done almost 800 updates to the long-term exhibition. Of course some things are very easy to update, others are not. And others are way more costly but we do them nevertheless. Trying to keep up with the difference, not only with the different knowledges and different studies that come out every week. But in a way that we can interpret the reality from a perspective that is quite challenging when we are facing the inequalities that are just growing, growing not only in Brazil and in Rio but especially on other parts of the world. And I think that the challenges that the climate change is putting us, putting right in our face that is going to make us…

It’s going to help to drive us to make us more creative on how can we really try to bring people from different backgrounds and different levels of study into this conversation. In the museum we try to somewhat bring people to be the protagonists of those narratives. In the case of museum we have a program that we have been setting up since the beginning of the museum called 10-year old Girls in Science. Where we try to ignite the flavor of science for especially in this critical age for girls, to go on and try to get study and jobs in the science fields. And in this year we have themed this workshop for the climate change. So the girls are talking about how hey want to be part of these worlds that is built upon access. So they are seeing the access in everything. They’re seeing access in shopping, they’re seeing access in deforestation, they’re seeing access in traveling and things. People that want more and more and more.

And they’re already seeing that, “Hey, we have to stop. We have to really create not only our limits but to question ourselves, why do we want so much?” Because if someone has too much of something, someone or some groups are having less and less of it every day that goes on. And they are asking those questions and we try to… And we’re going to have a seminar in November after this six months of workshop with the girls. And not only the ten-year-old girls but also girls from the first edition so they’re now almost 15 years old. They are also, some of them still participate in the program. And they are the ones who are coming up with ideas and videos and messages that want to spread out these words about the excessiveness that we are living in our society. And we see the same when we bring up people that live in the favelas in the communities, to be also the protagonists in some of our programs, to speak out of how they are living. Because they are the ones who sometimes lack of the quality of life as we know it.

But at the same time there are the ones living also with, creating longevity and in a house where you have several generations living within the same room. And we want to address how can the communities also try to come up with solutions, of how can we live in a world that we do not have one single roof for every single person, because that is not sustainable. And in a way we want, also not for only indigenous and black people only to talk about racism and indigenous issues. They have to talk about everything. And that’s what we are asking them to do because otherwise we will not be able to access the knowledge that they have as a group and as a society. And that somewhat in our industrialized and media guided society, we have been lacking of this ancestral vision. And this ancestral vision may also guide us into the future forward thinking vision. Because sometimes some of these groups, they have been coexisting with the natural resources that we depend so much, for centuries or thousands of years in a way that it allows them to regenerate.

Regeneration is the world I think, for these decades to come. And I think that we as a society, industrialize society must learn a lot from those groups.

Andres Roldan: I have an example of a project that we’ve been, in the last couple of years where… Well Colombia is a very fragmented country, where most of the population is in cities and the rural it’s more dispersed, and in a way more vulnerable. As many of you know Colombia is a country that has suffered many wars and social tensions. Which in a way are related to the model of living in cities and at the same time in a very rich environment of biodiversity and so on. And one of the things or the tools that for us is like a thing that works quite well is that, I have this brief story. We found out a couple of people in the countryside, of a desert here in the country. That seems they were children they collected fossils. It’s a place where there’s a lot of fossils of an ancient tropical jungle forest of paleo jungle. And they spontaneously collected toots and skeletons and shields and so on.

And it’s developing themselves a sense of understanding that they were… They didn’t have the education and the skills but at the same time they have the urge of to collect that and to protect that. And along the years they became self-made in, learning to gather that and they become increasingly more interesting for scientists to go there and visit them. And in a way this project started as an idea of how the museum could be related with a community that is obsessed with fossils. And of course the science museum has a lot of opportunities, that’s what’s about designing museums. So how do we create a condition where we can speak each other? Because the museum has the skills of setting up exhibitions and telling stories and so on. But the content and experience is themselves. So it became that co-created project where at the end we have a temporary exhibition that was designed based on the building, on the small house in a small village in the desert, where after the exhibition was set up it will became their museum to organize their own collection in there.

And this project became like a revelation for us. Which is, the museum should collect everything, should have everything, should design everything, should tell all the service for everything. Are we the museums the saviors and the messengers and the evangelists of everything? Or are we just a hub of tools and people and connections that in a way brings to these communities the opportunities of doing the difference? And I guess this is shifting the way how the mission of the museum is displayed, not only defined by how many visitors are we going to have where most of them could be tourists or just schools. But what happens to those villages and places and environments? Is the museum capable to create an experience where the visibility of what’s going on there happens inside the museum and at the same time you are helping to bring capabilities that brings them their own stories, their own visions, their own perspectives where they are? And I guess that’s one of the shifts in these times where museums perhaps were not meant anymore to be the super gravity collider of everything to be connected and collected there.

But like a more networked way of working and bringing sense to the people that should be the one that is having the things. And I guess that perhaps we in the future we’re not going to collect stuff but collect practices, but collect methodologies, collect relationships around the countries where we are as a way to deliver these values and not be only thinking in the place where we are. I just wanted to bring this story because in a way perhaps the future of the museum is not to become bigger and bigger but smaller and smaller, and into small pieces with different capabilities is spread around, which is perhaps the spirit of the times we are living. The network, universe that we are living is one that we all gain together. It’s a win-win bet where different voices and expressions could be part of a bigger picture of a change.

I don’t know if Massimo, do you have in Canada such kind of projects where in a way is not a center but different centers, different institutions that are working and networking to create value and content, useful to everyone but at the same time being useful for themselves. I don’t know. Such things are happening there or do you see that we still been our own castles of, in the core of where we are. How do you see that?

Massimo Bergamini: I think you’ve just raised a really important point. And it captured something that Leonardo also said. That the notion of museums as platforms. And when I think of that, I think of… And just bear with me for a second. I think of the the revolution that was introduced by Apple. 10, 12, 15 years ago where they decided to turn their technology, create a essentially a technology platform for innovation. And it just spurred and it’s incredible. Innovation in the field of applications and so on. Because suddenly there was a place for creative thinkers, to go to and monetize their creativity and so on. I think what you’re saying very much applies to museums. The museum should be a platform. A platform for co-creation, a platform for enabling, enhancing, uplifting local initiatives, ideas, creativity. Because the moment, to the point you made, Andres. The moment that we impose our own methodologies, our own paradigms, our own frameworks. We create these card rails, that limit human expression and human creativity. At a time when the guard ails should be absolutely removed. The challenges that we face as a society, require the input of everyone.

So, in Canada we are blessed with a network of national institutions that I think probably come closest to what you’re saying. And these are institutions that are networked through the government of Canada. But in terms of adopting that model as a paradigm change for the sector, we’re not there. But I think that is exactly where we are moving. I’m not sure if we were calling it that. When we talk about inclusiveness, at the end of the day that’s really what it should be about, shouldn’t it. It’s opening your doors to your community, not just as spectators but as contributors, as curators, as creators. And I think that is very much the future role of museums. And that’s where their power will reside.

Andres Roldan: Okay. I come back to you Massimo so we can open up some questions of the public that we have, and I would like to ask you what will be your main ideas that you would like to highlight? You just mentioned a couple of it but I guess you have some other notes and I can bring you mine, and try to round up of what we heard. Some ideas that could help to to, how museums should be embracing climate change and ecological crisis in this opportunity.

Massimo Bergamini: Yeah, thank you. Before I do that I need to have a quick shout out to some leaders in Canada, in the climate change field. The leadership team around the Coalition of Museums for Climate Change. I believe a number of them are participating. Bob James, David Jensen, Peter Ord, Viviane Gosselin, Marie-Claude Mongeon and Danielle Serratos. That is a group that is championing change and thinking along new lines, to try to create a much more engaged community. And ultimately not only around climate change. Because the social, and this is one of my takeaways from this conversation. We talked about climate change but it is also about justice. It’s about equality, it’s about inclusiveness. It’s about recognizing that our world is deeply divided, that they’re very deep chasms that separate us. The north and south, the east and west. There are cultural, political, economic divides. And yet we are trying to confront a global problem. And I think in this sense when, and perhaps it wasn’t said in those terms because the focus was really on opening the doors to our communities, our immediate communities.

I think the museum community, the global museum community must open its doors to a much broader and global conversation, in order to understand exactly where it can have an impact. As long as we speak amongst ourselves, for all the good work that is done. It is just self congratulation and we need to be able to tell a story that resonates with the larger public. And a larger public that is in a marketplace as is deeply fragmented, that is in the midst of a fundamental paradigm change in how it absorbs values, processes, information and knowledge. And I’m reminded of a quote from Neil Postman, American author and critic. 30 years ago he wrote that, “The role of museums is to provide answers to the fundamental question, what does it mean to be a human being?” And it is absolutely fundamental to this discussion. Because it is that definition of humanity, that unless it is rooted in some common values and a common understanding, we will never be able to bridge those divides.

And I think in this sense it is that the role of museums is to try to define that common definition that will allow us to find common solutions to problems that appear on the face of it, to be absolutely intractable. What is also interesting of it, just his comment which was made about 30 years ago. He was a critic of the impact of technology. Feeling that technology was driving change and we were becoming absolutely subservient to technology. I wonder what he would think about the technological revolution, the digital revolution that we’re experiencing today, and what it means to our role as museums and the kind of marketplace of ideas and information that it has created for us. And how we find our place and role within that space. So my final takeaway really is about… And I think it’s been repeated a number of times. A need to affect a change in our thinking, the need to recognize that our institutions are deeply rooted in outdated models. Be it colonial, patriarchal model and so on. Recognize it, acknowledge it, understand it and commit to change.

And one of the ways of facilitating this change is by opening our doors to our communities. Creating space for our communities to drive our thinking, to inform our thinking, and to contribute to the story that we are trying to tell.

Andres Roldan: Great. Thank you for the for the insights. I can see there’s a hand raising. I can see the hand of Emlyn Koster. I guess if you have a question please you have the mic open, to allow us to try to answer it.

Emlyn Koster: Well, thank you Andres. And yes thank you. My name is Emlyn Koster. My comment or question is from the standpoint that I’m a geologist before I was a museologist. And I was the initial Chair of the Anthropocene Working Group for ICOM. I would like to suggest that the climate change discussion needs to shed the silo boundaries that surround it. What I’m referring to is that, as many of you have said, we know quite clearly that nature and culture are one whole. Indigenous people have known this for a long time. We know that environmental health and human health are interconnected. What I think and what I wrote in the, earlier this year in a paper for the AAMs Exhibition journal, titled Paradigm Shift to Illuminate This Disrupted Planet. Climate change cannot be separated from all of the other changes which have been anthropogenic in their cores, that affect the hydrosphere, the biosphere, the lithosphere, the pedosphere, the frozen and liquid states of the hydrosphere. Nothing in the planet’s ecosystem works independently.

And so climate change can only be made for our public audiences and for our own research, in my view, given my vantage point into an inseparable holistic seamless whole. It makes it more complicated but I think as long as we try to imagine that climate change can be spoken about in isolation, we are actually not going to make any substantial progress because it must be recognized and communicated as part of a seamless, ecological whole planet, ecosystem. Thank you.

Andres Roldan: Thank you for the reflection. And I guess yes, indeed I think… Well in Colombia there’s a discussion right now on that. And I find this concept that I think Leonardo mentioned, about a regenerational culture. It’s not only about, because this idea of sustainability stills have a lack of things where in a way we are in an adaptive environment, where institutions are changing. And I guess one of the things that we didn’t spoke deeply but most of you mentioned was, of course the adaptations of the physical environment where we are. The museum and the best practices for water, energy and so on. But then it seems that is like the physical and biological problem but then is the cultural problem, which is in the core of our institutions. And I guess that perhaps one of the biggest challenges that we have is to put into our missions these kind of objectives of mind shift of social transformation as part of what we do.

It’s not anymore about just simple practices but also to embrace in our own mission that the programs, the activities, the educational side of what we’re doing it’s in a way committed or related directly or indirectly on that. And I guess that for me is a big message. The main words for me here has been the ones of co-creation, how to think with the communities in different perspectives of how to understand this. And I guess it’s not only co-create but also to link what you think it’s different but it isn’t and it’s related as Emlyn just said, everything is intertwined. Right now we are opening an exhibition on the aquarium. And aquariums are always about the fishes and what kind of forums and things they have. But which communities are related with those fishes. What is the relationship with those other living with ourselves? And how this is framing our own narratives, and how are we displaying explanation? It’s not only describing the world but enlightening that there are invisible connections between people, the planet, the objects that we are delivering, the living things that we are putting there.

And that’s a way, a more holistic way of approaching. And I guess the other main idea of network, of how the museum should not be understood only in terms of being the big collider or everything that rules the world as the dark star, but also as a network. How we feed each other in the small and in the big, in the communities we are. How we become into platforms of those communities, and at the same time how we are allowing ourselves to be programmed also by other voices and other participations. So I guess these are part of my notes. I don’t know if any of you have any other voice, and if we have any other question this is the moment. We are just a couple of minutes to follow up, perhaps one more question and I don’t know final thoughts of you, the ones that have been with us today. Frances?

Frances Morris: Yeah. Just a quick, I mean I completely endorse what you’ve been saying about the importance of community. But I think there is also a note of caution there that, let’s not abrogate our own responsibilities and put them all on the shoulder of our communities. And community comes in many shapes and sizes. And one of the things that I’ve noticed over the last few years that museums have this incredible, not just a platform but are a space of negotiation between very different communities, who have often opposite and conflicting demands for space, for empowerment, to be heard. And one of the things that really just chimed with me from whatever Emlyn, Emlyn? Koster was saying, is that actually the most important thing is to help everybody to understand the interdependencies. That the culture isn’t just, in my content isn’t just about visual culture. It’s that the culture that is what is requisite to sustain life. So that ecological thinking is the most important thing. And before we sort that out, actually it’s very difficult to work creatively with community.

Andres Roldan: Great. Leonardo and Massimo, any final thought?

Yes, I agree with Frances that bring up the creativeness, which is present in different communities is quite hard, quite challenging. Even because sometimes, most of the time they will question the way we museums put up those narratives and the way that we do it. And we must be prepared to hear and also to think about how can we reshape ourselves from insights. And I think that one of those reasons is that, museums have become a place for curating different stories. Even if it’s for objects or interactives or videos or whatever with that we are showing up. It’s telling stories about a group of people, sometimes about a collective endorsement. And having been the curators of such, how can we co-curate with other groups? Which is quite, quite challenging in this sense. Not only because climate justice may be the framework that we will be somewhat try to renegotiate, all those different clashes that is going to happen within our doors, and we must be prepared for it. And at the same time how can we alliance with other institutions?

And I’m just going to give an example of one that we have been doing, which is the forms alliance which is the future oriented synergy, museum synergies that we have been leading together with other science museums and centers. In the UK, for example, the Science Museum, in Japan the Miraikan, in U.S. the Climate Museum and some other museums that we have been discussing for the past three years, how can we really present narratives about the future, but especially of how those futures are impacting today’s actions? And I think that that’s the invitation that we should not only make to our audience but also to all the institutions to which we are connected in this and other networks. So thank you very much.

Andres Roldan: Thank you. And well, thank you for all your reflections and talks. I think this has been a very inspiring and interesting conversation. I have a lot of notes and questions of course to each of you. But the time is not always fair to all of us. So I don’t know if Joyce, I can see you there. If you want to make a closing for this conversation and thank you for hosting and allowing us to be part of this interesting conversation. If you want to add on the conversation that we just have.

Joyce Lee: Well, thank you Andres. You’ve done a tremendous job. And thank you to the panelists, Massimo, Leonardo and Frances. There is a new word that we all learned, the CC and C. Co-creation with communities. Let’s just remember that walking away from this session. And what you have all done is really trying to help us think through the physical and the cultural challenge of resiliency. Lifting that all up. And I’ll just take an opportunity to tie that back to you in Climate Week, because this year there is a lot of talk about climate finances. And many of you in the audience are actually tied to a larger organization. Organizations like Frances, that have strong endowments. So museums actually do have that purchasing power too. If you all think about how to have this conversation with your trustees, with your directors, with your advisory community. And the power of future donors, the power of your current endowments and really make a change and what Frances said about walking the talk, I really am 100% behind.

So all of you with your infinite wisdom and Andres’ skill in moderating us, we at AAM Environment Climate Network could not thank you all enough.

Thank you so much. And well and thank you to the participants. I invite everyone to, well to navigate and dive into the museums, to see all the programs of what they’re doing. And I want to make a final request, if possible, to the audience that we have. We would like to have a picture of all of us. So if there is a possible way you will turn on your cameras, the ones that still remain with us. So we can, well say we run… Hey, hello Dean. I can see some known faces here, with us. So, oh okay. So if one of the team can take us the picture. Well, I will suppose that somebody was with the camera there. So cheers to everyone. Cheers. Okay. Thank you so much. Well, I hope that we are seeing again. I really appreciate this invitation from AAM and the Network of Sustainable Museums, and for all of you to being active and been participating in this conversation. Thank you so much. Have a great day and well, goodbye.

AAM Member-Only Content

AAM Members get exclusive access to premium digital content including:

- Featured articles from Museum magazine

- Access to more than 1,500 resource listings from the Resource Center

- Tools, reports, and templates for equipping your work in museums

We're Sorry

Your current membership level does not allow you to access this content.

Upgrade Your Membership

Comments