The events of 2020 and 2021 forced museums to innovate in ways and at a speed that would have been unthinkable prior. Our hope is that 2022 brings about a time of reflection, where we take the time to process what we created under pressure. In that spirit, we’d like to offer this reflection by staff at the Minnesota Historical Society, as they begin to understand the internal impact of a seemingly “simple” pop-up exhibit hosted offsite in the second half of 2020.

—Laureen Trainer, Committee on Audience Research and Evaluation

The Project

In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, paper hearts started appearing in windows. Then, in some neighborhoods, stuffed animals. Occasionally, a full-fledged miniature art show popped up on someone’s lawn. All for passersby to take comfort in as they endured the early days of lockdown.

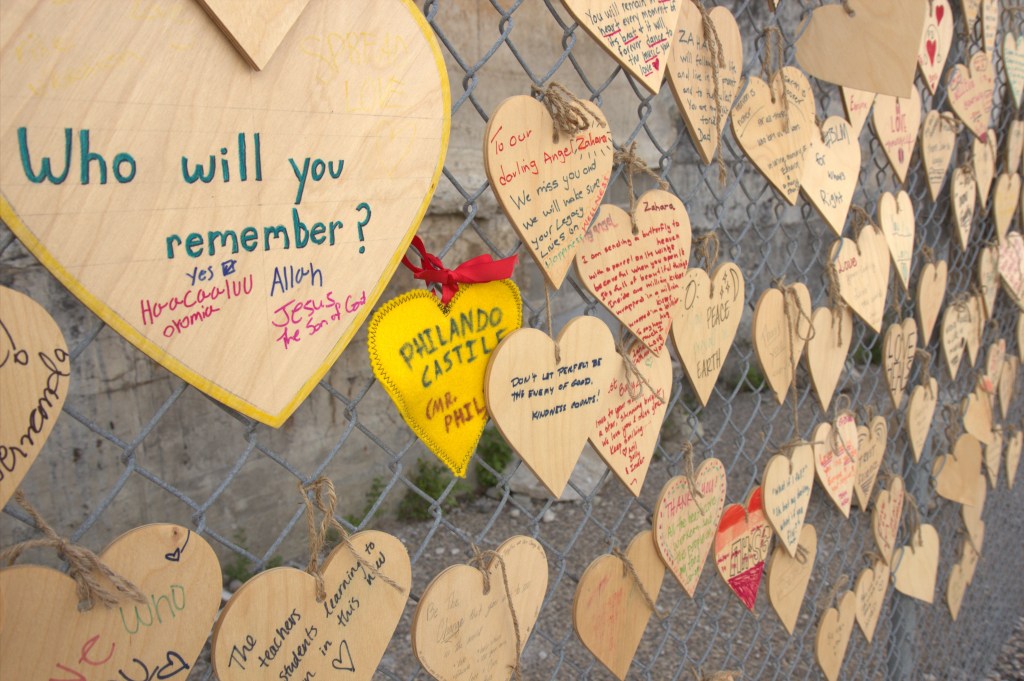

Then, in late summer 2020, another kind of pop-up emerged on the Minnesota landscape. Plywood hearts rattled on chain-link fences like muffled wind chimes. These hearts bore messages of hope, longing, outrage, and anguish. They were part of History at Heart, a series of interactive exhibitions by a small team at the Minnesota Historical Society (MNHS).

The initial idea for History at Heart emerged as a response to the dark early months of the pandemic. As the death toll in Minnesota climbed to one thousand, this profound loss weighed heavily on us all, as we tried to make sense of serving a public whom it was no longer safe to welcome into the museum. An outdoor memorial, then, was an opportunity to meet people where they were and to share our collective grief.

Then, on May 25, 2020, George Floyd was murdered by members of the Minneapolis Police Department. Our grief exploded. And in the aftermath, basic truths we’d once held were called into question. No longer could our personal experience be subsumed under our professional identities. And History at Heart could no longer be simply a pandemic memorial.

Across four different sites in Minnesota, History at Heart posed poignant questions about the enormous changes visitors faced amid the pandemic and in the wake of George Floyd’s murder: Who will you remember? What do you do differently now? What does safety mean to you? Using a stock of pre-cut plywood hearts, visitors could share their responses to these questions, or anything else they wanted to express about the times they were living in.

Because of limited staffing capacity, we were not able to take complete records of how many visitors came to each site or exactly how they participated (creating a heart, reading others, visiting multiple times, etc.), but we do have data to share. The first installation at the Mill City Museum in Minneapolis ran from July 18 to August 17, 2020, with signage in English, Spanish, and Somali, where one thousand hearts filled up in six days. On August 15, we took the exhibition up to Split Rock Lighthouse on Lake Superior and added Ojibwe translations to the signage. There, one thousand hearts filled within the first five days of the month-long run.

For our third installation, we partnered with the Hallie Q. Brown Community Center, an African American nonprofit social service agency in St. Paul. We collaborated with staff to rewrite the exhibition text to meet the specific needs of their community, before producing signage in English, Spanish, Somali, Ojibwe, and Hmong. At the request of leaders at Hallie Q. Brown, we also produced and delivered participation kits for higher-risk elders and students who would not be able to come to the site in person. Opening night of this installation was held on September 3, in conjunction with a screening of New Dawn Theatre Company’s short film A Breath for George. Within thirty days, people created another one thousand hearts.

A final installation opened on October 15 at Sabathani Community Center in Minneapolis, but we were not able to collect data from it.

The Process

To a large degree, the realization of History at Heart depended on the team’s ability to be nimble, responsive, and decisive. The growth of this exhibition necessitated a departure from the multiyear design process MNHS typically follows. It wasn’t just that the purpose of History at Heart called for us to act in the moment. The pandemic forced our network of twenty-six historic sites and museums to shut down, sending the institution hurtling toward an unprecedented financial cliff. Eventually, our leadership resorted to massive furloughs and layoffs. Our team—those of us who were left—were weary. There was still so much to do, with half as many people.

So, for this project, we intentionally kept things loose and simple, rather than polished and refined. The structure of the team was less formal than usual. We met in short, as-needed meetings as a small, fluid coalition. Our priority was to support each other as we tried to make this thing a reality. We recognized the unique skills and relationships we each brought to the table, including previous partnerships with Hallie Q. Brown and Sabathani. Perfection gave way to experimentation, fear to trust.

We built in opportunities to iterate. For example, because impermanence and affordability were virtues in this case, we first considered cardboard for the material of the hearts. Before installing the first exhibition, however, a Midwestern thunderstorm rolled in, reminding us that a higher level of durability was necessary if we wanted this to last more than a weekend, so we switched to plywood.

Observations

In each of its iterations, History at Heart became something more than anyone on the exhibition team could have imagined. The sheer range of emotion displayed on the hearts was something to remark upon. Mournful tributes to loved ones gone too soon hung next to promises of a better tomorrow. Raw anger at the violence wrought by systemic racism contrasted with the scribbles of a toddler. Political slogans were undercut by silly jokes.

We were equally surprised by the myriad ways people interacted with the exhibition. Many would find a spot nearby to sit, alone or with a group, as they worked on their hearts. Some didn’t bother making a new one, but added to one already hung on the fence. A handful of people even took the hearts home to complete, returning later to reveal their masterpieces. Visitors brought loved ones back to share their contributions and see how the space around them had filled up. Others opted to just read the hearts, flipping carefully through the layers built over the course of several weeks. These asynchronous conversations seemed to help fill some social void created during the months of quarantine. While innovative digital spaces partially addressed this void, the power of physical spaces resonated.

Onsite and via social media, we saw overwhelmingly positive responses to the experience. Many people expressed their gratitude for the project, and in at least one memorable instance, for the translations specifically. People described the beauty of the exhibition—the strength, hope, and surprise they found in the messages. While few visitors responded directly to the prompts we provided, we didn’t mind. They were connecting with each other.

Lingering Questions

As simple as this exhibition was on its face, compared to the others we take on, it reverberated throughout MNHS as well, leading to tough questions that we are grappling with more than a year later. We have no answers, but we wanted to share our questions with the field, as we believe they should be contemplated by the entire field, not just the staff from one institution, as in many cases they challenge the very notion of who creates history and the importance of collections and institutions.

What is the role of interpretation in exhibits?

At MNHS, like many institutions, we have an expectation that any experience or interaction should be tied to learning outcomes. This project challenged us to think about what we want people to learn and the type of learning we value. Rather than experts, we stood on the other side as the listeners, as students. History at Heart led to revelations and reflections that are outside of a textbook or traditional historical teachings. It prompted people to learn about the importance of being in community, of sympathy and empathy, and of relying on one another in moments of sadness, grief, stress, sickness, and isolation. Where does this leave us in terms of thinking critically about what we are requiring from our exhibits and from our audiences? What does it mean for people to learn from an experience? Is all learning equal?

What happens when the public takes your exhibit in a totally different direction?

At the beginning, we were trying to craft a memorial, a place for people to come and grieve amid the loss of the year. But the public took it in a completely different direction, and it became more lighthearted than any of us imagined. The exhibit became the site of love and hope and laughter and joy. Our communities didn’t need quiet reverence—they needed and wanted to play and interact. The design of the exhibition allowed for the public to take control of the narrative and the tone, but as we mentioned before, this exhibit was very different from our traditional exhibits. What do we take away from this experience? How do we factor in the unexpected twists that the public can bring to a narrative? Do we design for that? How? And what does it mean for our historical narratives? For our learning goals?

What is the importance of our institutions?

This pop-up exhibition was self-directed; it was designed to allow people to go on their own journey and discover their own thoughts and reflections. In many ways, this concept is a huge challenge to our institutions, as it pushes against the notion that museums are supposed to curate and present. For us, it led to questions about the role of the museum and of the expert voice. It played into the fieldwide question about the democratization of museums. It opened up questions about the role of our physical, formal spaces while championing interaction with physical items, in this case wooden hearts.

What does it mean when we don’t know who we are creating for?

This pop-up exhibit came to be on the side of metal fences and along the shores of a great lake. It withstood rain, snow, wind, and sun. It was not marketed by the museum. And yet, people walked by, biked by, came once, came multiple times, brought family and friends, decorated four thousand hearts, and created connections both fleeting and deep. But this audience came completely by chance. We didn’t know who would interact with the exhibit, whose lives it would touch, or who would interact with whom. This is a huge change from how we normally design and market exhibits and how we think about our market and our visitors. Who came to the pop-up exhibit? Were they the same people who normally come to MNHS? We don’t know, but there is a good chance we reached people who have never engaged with our building or our programs. What do we do with this unintentional community moving forward? How do they fit into our traditional exhibits and programs?

How do we talk about our visitors?

This unintentional and somewhat unknowable community challenged our notion of our visitors. Internally, we use Falk’s visitor identity categories when thinking about planning, interpretation, and themes, and generally we program for affinity seekers and explorers. However, History at Heart challenged these categories for us. Perhaps the pandemic has shifted some of those categories. Or the combination of the pandemic, racial unrest, job disruptions, social upheaval, and the unknowable path of the virus combined with the location and nature of the pop-up exhibit, creating visitor identities that before now haven’t existed. Did this experience create new visitor identities? What are they? What do we do with them? How do they inform future planning?

What is the role of the object?

In this exhibit there were no valuable objects. We didn’t bring out any objects and use them in a didactic manner. We weren’t asking people to reflect upon anything from the collection. Instead, the process of collecting stories transformed the process of exhibit development. We allowed people to create their own objects, develop their own histories. We provided the public the materials to create their own reflections and mark their own thoughts about 2020. In a way, this was a massive public history project, created outside the walls of an institution and without the demands and weight of a traditional exhibition. What role does this have in the field? What do we do with this history? What will we take from those hearts as we interpret this time from the other side of the pandemic?

We invite you to think with us and to add to this conversation!

This blog post has been adapted from an article originally published in the journal Exhibition (Fall 2021) Vol. 40 No. 2. A web version of the full article will be available in Fall 2022 at https://www.name-aam.org/.

The History at Heart Team

Jeni O’Malley, senior exhibit designer

Maggie Schmidt, exhibit developer

Ami Naff, exhibit researcher

Emily Marti, graphics designer

Lisa Friedlander, project specialist

Hannah Novillo Erickson, 3D objects associate curator

Rebecca Gillette, community programs

Danielle Dart, public programs specialist

Andrea Reed, senior digital media manager

Kelsi Sharp of Sharp Design Co., contracted fabricator

Thank you museum community and I look forward to continuing conversations, more questions, and the growth that will inevitably come from that interaction. To see more photos or make a connection with me please feel free to contact me through http://www.jeniomalley.com.

I also want to mention Ami Naff’s huge contribution to this article as the MNHS team’s primary writer. Ami’s writing talent and dedication to community was invaluable. I can’t say enough positive things about the contributions Ami provided. I am lucky to work with such exceptional people.

Now: If MHS would just answer its correspondence.