Some of the newest, and most defining, jobs in the current era of museums are those focusing on decolonization and diversity, equity, accessibility, and inclusion. In recent years, as more institutions have come to prioritize undoing inequitable structures and creating more welcoming and inclusive cultures in their place, they have begun to invest in full-time staff dedicated to leading these monumental tasks.

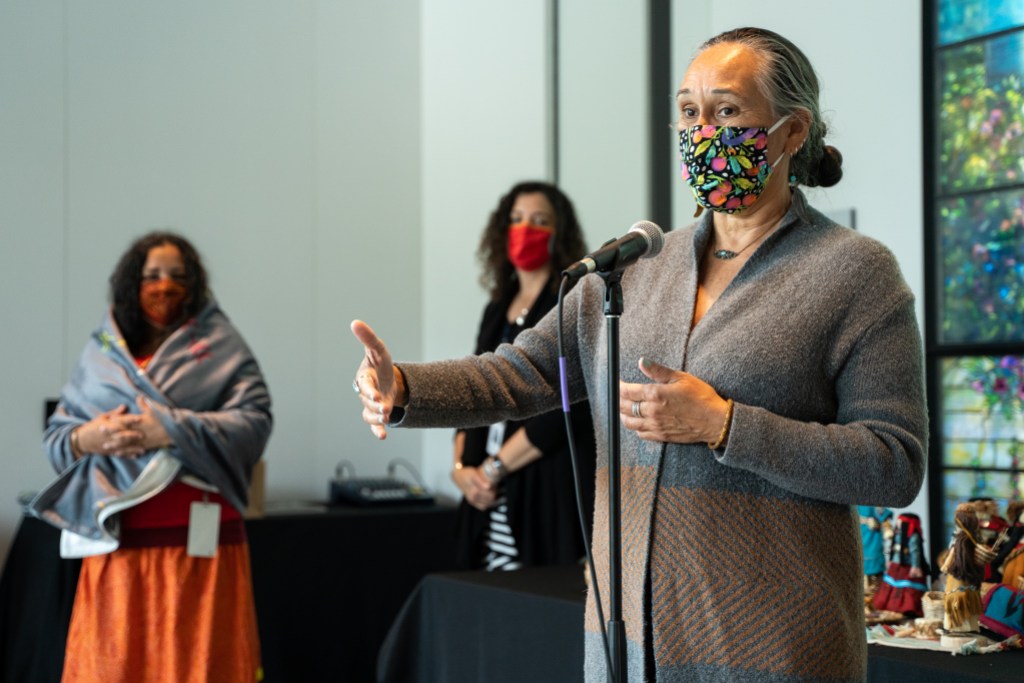

One of the institutions that have made this investment is the Burke Museum in Seattle. To coincide with the opening of its new building in 2019, the natural history and culture museum on the campus of the University of Washington has foregrounded equity, inclusion, and tribal consultation—growing a landscape of more than fifty native plant species around its campus, opening an independently owned and operated café dedicated to Native foods, and working steadily to build a deeper relationship with its Native communities, to name just a few of a long list of accomplishments so far. The engine behind this work is the museum’s newly assembled Decolonization/DEAI team, consisting of Polly Olsen; Director of Diversity, Equity, Access, Inclusion & Decolonization/Tribal Liaison; and Aaron McCanna; DEAI/Decolonization Coordinator. We spoke to Polly and Aaron about what brought them to the work, what brings them joy, and what keeps them going in the face of challenges.

Tell us about your role at the Burke Museum. What are the main goals and responsibilities of your jobs?

Polly and Aaron: We are the Decolonization/DEAI team at the Burke Museum. In a very basic sense, we work to foster and create relationships inside and outside of the museum that are genuine, reciprocal, and beneficial, with the common goal of improving the lived experiences of people. Our goals and responsibilities are really varied, which is part of the reason why we love our jobs. The freedom to pursue decolonization and DEAI in a non-colonial way is essential to the success of the work.

What led you to get involved with DEAI and decolonization work?

Aaron: I became interested in decolonization because I was originally interested in academic science and archaeology, but as a mixed-race Native person I realized I wanted to do more to support the communities that raised me. I wanted to help create a system where people could be themselves freely, and to realize the incredible value of our communities, not within Western science, but on our own.

Polly: I got into this work twenty years ago when decolonization became the buzzword in academia. I wanted to bring that term back, ask the communities what they want, and turn that academic term into something that actually benefits our communities. To me, decolonization is about changing the power dynamic of organizations who come in and tell, inform, or demand from our communities. Instead, I want to see a culture of co-creating and co-managing science and curriculum that facilitates access to our ancestors.

What is the best day you’ve had on the job, whether it involved a particular project or accomplishment, or even just a fulfilling moment?

Polly: One of my best moments came after a difficult day that created harm to some of our Tribal communities, when we were moving too fast in consultation about our camas field, an endangered traditional ecosystem that we cultivated on the museum grounds. Afterward, I sat with the camas in the field and was able to get out of rumination on my mistakes and get into introspection and learning. I realized decolonization is a journey and I needed to forgive myself, to remind myself that I am somewhere along this journey as everyone else is. What made it the best day was that “oh” moment: I walk in both worlds. Sometimes I accidentally harm despite my good intentions, and I am learning how to come back and forgive and heal back into the decolonization, equity, and inclusion process.

Aaron: I can think of a lot of good moments I’ve had in this job. I love my work. One of the things that really stuck with me was when I was wandering around our biology collections, and I found two of our scientists talking about decolonization without any of our “decol” people there because they were excited about it. I could see their genuine desire to make the museum a better place for people like me. That made me excited because I think that’s evidence our work is having an impact.

What do you envision as the future of a decolonized, inclusive museum? What do you dream of seeing from museums one day?

Polly and Aaron: We dream of a museum that exemplifies a decolonized discourse. One in which we can truly talk to each other, heal, and feel joy together. Where we can support each other and learn from each other. One of the trickiest things about decolonization is that people expect an end goal. They want a toolkit to do it instead of sitting in the process. But decolonization is a relational concept, and good relationships don’t have an end goal. Decolonization is a never-ending process; a movement that changes over time as people do.

What makes decolonization and DEAI work in museums different from other fields? Are there unique aspects to working in this setting compared to others you’ve experienced?

Polly: In many ways decolonization and DEAI work are applicable to any field because they focus on systemic issues that are far broader than a museum. One unique aspect of the Burke, though, is how long we have had our relationship with Washington State tribes. The Native American Advisory Board at the Burke has been around for over thirty years, and it has really taken that long to raise that relationship and give it the care needed for it to be genuine and reciprocal. Now, NAAB members are proud of their relationship with the Burke, and the relationship I share with them feeds my soul. Moving slow to build a genuine, reciprocal relationship is a unique and immensely valuable thing in this field.

Tell us about the Burke’s land acknowledgement statement. What was the process for writing it like, and what makes it different from other land acknowledgements people may be familiar with?

We wrote a whole blog post about that!

Aaron, you’ve said that your goal is to go beyond just educating people about marginalized cultures and histories to think of inclusion on a deeper level. What is that deeper thing you’re striving for?

Aaron: At the end of the day, I don’t want to simply educate people about Native communities and other marginalized cultures. I want to support those communities in finding joy and pride in themselves, free from the constraints so often placed on us. If we aren’t seeking to better people’s lives through that education, I struggle to see the point.

History is important, and it helps ground us and helps us to understand why the world is the way it is today. It is also profoundly burdensome on our communities to only focus on the harms we have experienced. A major focus of mine is finding a way to bring benefit to these communities. Part of that is in measuring success not just by the stats and numbers of how many “diverse” people we get to interact with the museum, but in what we can do to support people in healing and pursuing joy, in their own ways.

How do you maintain optimism for your work despite the deep-rooted issues and nonlinear progress that can come with it?

Aaron: Decolonization and DEAI is a constant, ongoing process. It doesn’t have an end goal. I think the process itself is incredibly fulfilling, and involves working with so many people in really wonderful ways. Because I don’t have an end goal in mind and am instead focused on fostering better, decolonized relationships, progress can’t be defined on a two-dimensional graph. That being said, this process involves many difficult conversations and a lot of emotional labor. I’m happy in my role because I really do believe the process of decolonization is worth undertaking, and I feel the benefits with the communities I work with. At the end of the day, if I can improve our organization and our world even just a little bit, I’m happy.

Comments