At King Manor, education about the environment and the historic house go hand in hand.

This article originally appeared in the July/August 2022 of Museum magazine, a benefit of AAM membership.

You might not think a historic house museum in Jamaica, Queens, in New York City would be a good place to learn about climate change. But at King Manor, we believe we are perfectly positioned to address this important and timely issue.

King Manor, which sits at the center of the only major green space in a bustling urban neighborhood and commercial center, interprets Rufus King’s political legacy and antislavery history to teach critical thinking for a healthier democracy. King was a framer and signer of the US Constitution, a US Senator, an ambassador to England, and a vocal antislavery advocate. Also a dabbler in agricultural science, King improved his 160 acres of land, turning it into a successful working farm, using paid labor, and making scientific strides in the interest of the new nation’s agricultural health.

A community-minded institution, King Manor, which employs three full-time and two part-time employees and has an annual operating budget just under $300,000, regularly collaborates with local organizations and businesses and participates in initiatives that benefit the people in our neighborhood of Jamaica and wider New York City.

According to the 2020 census, 18 percent of the population of Jamaica identifies as Latino, 14 percent Asian, and 59 percent Black. A significant number of residents are recent immigrants with limited English language skills. Furthermore, according to the New York City Department of Education, fully 90 percent of the district’s schoolchildren are eligible for free or reduced-cost lunches.

King Manor is the only historical resource serving this underserved, but rapidly developing, community. Every program at King Manor is designed to encourage critical thinking in learners of all skills and experiences, creating spaces for our visitors to mindfully engage with history in order to promote a healthier democracy as a whole.

For several years, we have incorporated aspects of environmental history in our school field trips and public tours, but the pandemic shone an even brighter spotlight on the importance of green spaces to our community, prompting us to launch a wider set of public initiatives focused on environmental education, sustainability, and climate change.

Making Space for Environmental Education

King Manor was the first cultural institution in New York City to sign on to “We Are Still In” and is the first public food-scrap drop-off in Southeast Queens. And we have been bringing environmental education into our humanities practice for years by including it in the narrative of our public tours and especially through our ethnobotanic garden and seed library.

A large body of research demonstrates that gardens have the ability to improve mood, develop social and emotional skills, and promote health and wellness. Our mission is to “teach critical thinking for a healthier democracy,” and we operate with the understanding that a “healthy democracy” must include a healthy populace and a healthy planet.

We have partnered with Reclaim Seed, a grassroots organization reconnecting people to their foodways—the cultural, social, and economic practices relating to the production and consumption of food—through history, education, and plants. In June 2019, we installed a teaching garden that focused on ethnobotany: activating the historical roots of a previously underutilized position of our lawn by interpreting the agricultural history of the King family. The garden, which Reclaim Seed stewarded in its first growing season, also served as a living archive, exploring the ancestral foodways of the Indigenous Lenape, enslaved and freed Africans, and early European settlers of New York City.

Younger students were particularly excited to see the Three Sisters planting technique—in which three plants grow symbiotically to deter weeds and pests, enrich the soil, and support each other—in action after learning about this in school. Although the park’s squirrels had their own plans for most of the produce we grew, we were able to successfully harvest seeds for our free seed library and used the next growing season (during the height of the pandemic) to grow crops for seed, promote local biodiversity, and encourage visitors to see themselves as potential stewards of land.

In response to pandemic-era limitations on school field trip opportunities, King Manor has partnered with the Growing Up Green Charter School in Jamaica to develop an ongoing STEAM (science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics) garden program for students in grades K–5. In the teaching garden’s third growing season, these students have taken ownership of the garden beds, regularly coming to King Manor to work in the garden and explore the science of pollination, the foodways of different historic and modern cultural groups, and the civics of food production. Compost Project NYC and the Queens Botanical Garden are sharing their expertise, including assisting with compost training for teachers.

Working with the garden also taught us, the museum staff, a lot about land stewardship. Since building the raised beds, we are all much more attuned to the effects of climate change on our little plot, noticing when extreme weather affects the growing season, such as a late snowstorm in the spring of 2021 that stunted the growth of plants that had already sprouted. This made us more aware of similar impacts of climate change throughout the park where our museum is located, such as buds that never get to bloom because of unexpected cold snaps or leaves that fail to change colors until December because of warm fall temperatures.

This has made us think about further-reaching impacts of climate change on the natural environment and agricultural production, like apple orchards losing fruit or the decreasing environment suitable for the growth of sugar maple trees, as global temperatures rise. Although we had all been aware of such phenomena, experiencing it firsthand through a closer relationship with our natural environment has been eye-opening.

We hope that by increasing community members’ ownership of the garden, they will also start making these connections between their immediate environment and global climate change. This connection between the familiar, or microcosm, and the macrocosm is the foundation of our approach to fostering critical thinking. It is how we structure everything from school tours to art installations and exhibits.

Leveraging Technology

Our global responsibility to combat climate change doesn’t end when we go inside, and we felt that our period rooms offered a unique entry point for thinking about environmental history in a domestic space. To that end, we recently launched “Climate Change at Home,” a technology-enhanced tour of the museum that helps visitors understand the history of climate change and addresses climate anxiety by bringing this global phenomenon to a household level.

This technology-assisted experience allows visitors to examine the materials, manufacture, and global environmental impact of the 19th-century objects in King Manor’s period rooms. As visitors scan the room with their smartphone or borrowed iPad, their device will pick up input from radio-frequency identification (RFID) tags that are hidden inside or behind objects that curatorial and educational staff have selected for the tour. Since RFID tags can be read at a distance, this technology has allowed us to add extra layers of meaning to period room displays without disrupting their historic setting.

For example, visitors can see how mahogany furniture led to the deforestation of many Caribbean islands, how the spice trade meant both an expanded palette and carbon footprint, and how an indigo-dyed blanket is a reminder of early monoculture practices in the US that continue today to the detriment of soil health and biodiversity. By the end of the tour, visitors can “read” the climate history of objects in the museum on their own—and start thinking about how their everyday choices are part of a larger global phenomenon, helping them understand climate change on a more personal level.

Our goal is to empower visitors to understand and recognize how human actions have impacted the environment over time and today. We hope that visitors will not only recognize the larger environmental histories of the household objects in the museum, but will also continue to use this critical approach to understanding the world around them long after their museum visit is over.

History is not teleological but a result of individual and collective decisions. At King Manor, we hope to help visitors understand the historical roots of current issues so that they can make effective change.

“Our mission is to ‘teach critical thinking for a healthier democracy,’ and we operate with the understanding that a ‘healthy democracy’ must include a healthy populace and a healthy planet.”

Adding Space for Local Art

A community-wide survey in 2017 identified the need for more places for local artists to display their work within their own community. So during a pandemic-induced mandatory closure of King Manor in 2020, we turned an underutilized storage area into a beautiful gallery space. Since opening the space, we have hosted several contemporary art exhibitions (almost all community curated). Most of the artists’ work has explored social justice themes, and the majority have had an environmental justice focus.

A community-wide survey in 2017 identified the need for more places for local artists to display their work within their own community. So during a pandemic-induced mandatory closure of King Manor in 2020, we turned an underutilized storage area into a beautiful gallery space. Since opening the space, we have hosted several contemporary art exhibitions (almost all community curated). Most of the artists’ work has explored social justice themes, and the majority have had an environmental justice focus.

For example, Hayoon Jay Lee’s Beyond Life and Death invited viewers to consider their individual relationships with food along with the connections between foodways and the environment. She used objects from the museum’s collection, bones (both modern and archaeologically recovered examples from the museum’s grounds), and encapsulated grains of rice to create a multilayered tablescape installation accompanied by a video of the artist and a diverse group of women at the table talking about food and globalization.

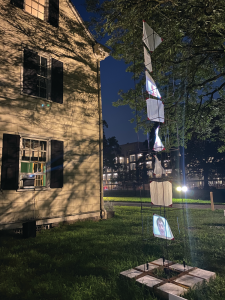

Sari Nordman’s Tower (above, right) projected multilingual interviews about climate change on a tower constructed of metal and reclaimed plastic sheets. Meant to evoke the Tower of Babel, Nordman writes that her piece told a “story of greed and the value of cultural differences. … The interviews are recorded in the interviewee’s native language to emphasize the global impact and responsibility in fighting climate change.” The message of this piece, installed on the museum’s lawn, fit perfectly with the multicultural setting of Queens and King Manor’s mission and vision.

Resources

Jennifer Anderson, Mahogany: The Costs of Luxury in Early America, 2012

David Blackbourn, The Conquest of Nature: Water, Landscape, and the Making of Modern Germany, 2007

Andrea Feeser, Red, White, and Black Make Blue: Indigo in the Fabric of Colonial South Carolina Life, 2013

Kieko Matteson, Forests in Revolutionary France: Conservation, Community, and Conflict, 1669–1848, 2015

Erin Stewart Mauldin, Unredeemed Land: An Environmental History of Civil War and Emancipation in the Cotton South, 2018

Comments