This article originally appeared in the July/August 2022 of Museum magazine, a benefit of AAM membership.

Museums can simultaneously make their exhibitions more sustainable and improve social equity.

It has been six years since President Barack Obama declared a state of emergency in Flint, Michigan, a majority-Black community, due to highly contaminated water. Between 2014 and 2016, tens of thousands of Flint residents were exposed to lead-tainted water, resulting in illness and death.

This revelation and the subsequent mitigation efforts allowed many Americans, for the first time, to consider and examine the environmental harms and disparities that plague nonwhite people, largely because of systemic and institutional racism. Flint was but one jarring example of many that expose parallel but inequitable Americas.

The reality is that for decades, more people of color than white people have experienced the deleterious effects of lead, asbestos, toxic air, and other pollutants. Historically, law and tradition informed by prejudice and racism created practices that continue to be deeply problematic. What is sometimes ascribed to poverty alone has roots in racial injustice.

What does this have to do with museums? How we build new exhibitions affects sustainability and social justice in our communities and around the world. Until we, as a field, look critically at our own practices to see if we, too, are perpetuating harm, we will not be able to honestly take social responsibility and engage in collective healing.

Using Sustainable Materials

All museums can learn from what small museums already know: the best way to conserve limited resources is to design exhibitions so that elements can be disassembled and reused. Think “clips and screws, not nails nor glues.”

Cultivate mutually beneficial community partnerships. Some museums have partnered with local theaters or film boards to reuse plywood or other construction materials from former sets in their exhibits. Or you could also find materials at construction salvage warehouses.

The OH WOW! science center in Youngstown, Ohio, recently created an exhibit on mental health for kids. Using salvaged construction materials that included silk daisies, stuffed baby chick toys, a smiley face spatula, and yellow watering can, CambridgeSeven and museum staff created a large “Wall of Shine,” which community members filled with yellow objects that make them happy. This exhibit successfully tackled both mental health topics and sustainable design opportunities. The museum also repurposed exterior signage in its new gift shop.

CambridgeSeven for OH WOW!, Youngstown, OH

Many products will try to appear sustainable even though they are not. This is called “greenwashing,” and to navigate this disinformation your exhibit staff will need to learn sustainable material basics. The good news is that third-party certifiers have done much of this work for us (see the Resources box on p. 25 for a list of free sustainable building material databases), but it is important to learn which sustainable certifications are biased advertising and which are based on data.

Environmental product declaration (EPD) reports provide the energy use and carbon footprint of a specific product from extraction and manufacture through its useful life to disposal (cradle to grave). Health product declaration (HPD) reports are detailed, self-reported ingredient lists for building products. Ask your suppliers if they have EPDs and HPDs for their products.

Select materials from companies that have a long track record of sustainable practices and have examined their environmental and social justice impact. These companies tend to continuously improve their processes and treat their own employees well. Look for companies that have take-back programs in which they recycle their products at the end of their useful life.

In addition, look for the International Living Future Institute’s “Just” certification label, which identifies the diversity and equity within organizations. Or seek out certified B corporations (B Corp), which are for-profit companies that have had the quality of their products, how they treat their employees, and their relationship with their communities examined by B Lab, a third-party certifying agency. When possible, engage women-owned and minority-owned businesses.

The International Living Future Institute has a new simplified Core Green Building Certification that can be used to certify the sustainable aspects of your exhibition. Expedition Blue, a series of distributed-site information waypoints on Cape Cod, is pursuing this certification for one of its kiosks, which provides a place to enjoy beautiful views and fosters pride in the local, water-based “blue economy.”

Reducing Energy Use

Reducing the energy use of exhibits can save institutions a lot of money. The first step, if you have not already done so, is to replace all incandescent light fixtures with LEDs in your museum. Many local governments and energy companies have excellent incentives to subsidize replacement costs, and the energy savings will quickly cover any remaining expense.

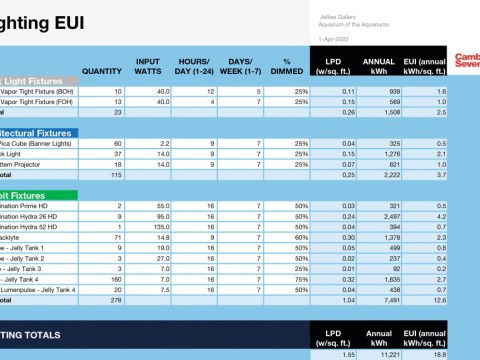

When designing new exhibition galleries, use a simple spreadsheet to track the daily watts used for each light fixture. With this data, you can calculate a gallery’s lighting power density (LPD), which is the maximum energy load if all your lights were on at full power. Using the square footage of the building, you can also easily calculate the annual energy use intensity (EUI), which is measured in kBtu per square foot. The same spreadsheet can be used to quickly calculate energy use of audiovisual experiences. (See an example spreadsheet on p. 23.)

EnergyStar’s national baseline for all energy used in museum galleries is 56 kBtu/sq. ft. Your museum can set a goal to never exceed this national average and to lower energy use in future exhibitions. To do so, install daylight and occupancy sensors so that you are only drawing energy for lighting when needed.

Finally, look for fixtures and audiovisual equipment that are compliant with Restriction of Hazardous Substances (RoHS), which indicates that they have been tested and certified to be free of 10 hazardous substances, including lead, mercury, and cadmium.

Sustainable Graphics Production

Over the past decade, printing methods have become much more environmentally sustainable. Gone are photographic chemicals and most solvents high in volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Eco-solvent inks use a base alcohol to replace aggressive solvents, UV printers cure inks with UV light rather than through out-gassing, and water-based latex inks are certified by GREENGUARD Gold, meaning they meet ambitious standards for chemical safety.

A sustainably minded graphic print supplier can increase environmental and community benefits by sourcing, testing, and employing locally manufactured and environmentally sustainable substrates. High-quality, high-performing roll-and-sheet products without PVC (see the PVC sidebar on this page) and containing both recycled and sustainably sourced material are available from Hewlett Packard, Monadnock Papers, Ultraflex, and Fisher, among others.

Ideally, your print provider will have a sustainability management system (SMS) in place. This operating framework encourages waste reduction and use of environmentally sustainable materials. It also encourages a system-wide sustainability approach involving energy use, carbon footprint, and other social and ecological impacts.

Even mounting substrates can be thoughtfully sourced. For instance, acrylic can be replaced with recycled-content resin sheet made from soda bottles. Plyboo or ApplePly are excellent alternative fabricating and mounting substrates.

Consider the following as you plan the image side of your exhibition:

- Determine a desired life cycle for your graphics. Some materials are more environmentally friendly than others, but you must strike a balance between quality and longevity. In some cases, a sign using slightly less eco-friendly, yet more durable, material may be a higher-value and lower-carbon solution if it will need to be replaced less often.

- Consider a modular design approach so that updating images and copy can occur with less material.

- Use print and mounting substrates with recycled and/or recyclable content. Some brand names that are completely non-PVC include PlyVeneer’s BioBoard or PCA’s Falconboard, Monadnock Envi Wallgraphics, or Cooley Group’s EnviroFlex PE poster, banners, and translucent substrates.

- When possible, install graphics with mechanical fasteners as opposed to double-stick tape to eliminate volatile organic compounds (VOCs) associated with most adhesives.

- As you are thinking about carbon footprint, determine the manufacturing location of both the raw input materials (print material, inks, substrates) as well as the printer and fabricator. Many graphic products sold in the US are imported from other countries, thus involving much more transportation energy.

Setting Goals for Your Museum

After your exhibit design team learns the basics of sustainable products and environmental justice, identify the goals for your museum exhibits and future installations. Following are some questions to consider.

What levels of diversity will you seek in your internal team, in the people that you hire, and in your community partners? Who are the people making decisions about acceptable risks as you navigate price, convenience, durability, and equity?

How will you design for disassembly and incorporate salvaged materials into your work? What products will you seek to avoid for environmental justice or for visitor health? What are your energy use goals? What standards do you have for product durability? Even the lowest-carbon material has a higher carbon footprint than one that doesn’t need replacing.

The hazardous environmental effects of climate change, although primarily caused by privileged communities in the global north, disproportionately affect BIPOC communities in the United States and in the global south. Any improvements to current practices that reduce our carbon footprint can positively affect environmental justice.

This is challenging work that is sometimes difficult to navigate. Be patient with yourself in this journey, but do not let the complexity stop you from improving your internal practices. And as you strive to do better, use all your communication channels to share the story of your sustainability and equity work honestly and loudly to encourage others.

Resources

Sustainable Minds Transparency Catalog

Lists of building products with EPDs and HPD transparency documentation

transparencycatalog.com

Mindful Materials Library

Extensive data about building products

mindfulmaterials.com

International Living Future Institute Declare Labels

Brief summaries of sustainable attributes of materials

declare.living-future.org

Cradle to Cradle Certification

Third-party certification of products focusing on safety, circularity, and responsible manufacturing

C2Ccertified.org

HomeFree Product Guidance

What to look for and what to avoid with interior building products and finishes

homefree.healthybuilding.net/products

PVC: A Social Equity Case Study

PVC, polyvinyl chloride, is a common plastic widely used in fabrication of large graphic wall murals and in expanded media boards. PVC is cheap, durable, long lasting, and ubiquitous. But its use is an example of how decisions of convenience can negatively affect communities with less power.

The manufacture of chlorinated polymers in PVC produces dioxins, which are among the most potent toxins known to humans. According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), dioxins can pollute air and water, causing cancer, reproductive and developmental problems, damage to the immune system, and interference with hormones.

Research by ComingCleanInc.org found that the high-risk, or “fenceline,” communities near these production plants are disproportionally BIPOC communities. According to a December 2019 EPA study, Integrated Science Assessment for Particulate Matter, race is the most significant predictor of a person living near sources of pollution.

Comments