It’s no secret that the pandemic hit certain communities harder than others. Disasters—be they environmental, social, or public-health-related—often have this effect, exposing inequity both in who can shield themselves from impacts and who can easily recover afterward. We tend to applaud communities that bounce back easily, crediting their foresight in planning ahead to be resilient, but in reality, making these plans requires resources that many communities do not have.

The story ahead describes how a cultural organization attempted to address this inequity. In Springfield, Massachusetts, the Trust Transfer Project (TTP) came to fruition at a time of public health emergency. The project’s response and recovery efforts helped the community build up its resilience for future disasters, demonstrating in the process that the greatest resource the city had was there all along—its people. This story highlights how taking a creative, grassroots approach to community engagement and outreach can lead to cultural organizations having a direct social impact in the communities they serve.

In 2021, local health organizations approached the Springfield Cultural Partnership and Community Music School of Springfield (CMSS) asking for help creating a public health campaign for Springfield’s communities of color.

From the get-go, staff from the two organizations knew what they wanted to do—to hire and compensate local BIPOC artists to support public health messaging. Vanessa Ford, a voice teacher at CMSS who took the reins as the Trust Transfer Project’s (TTP’s) Project Manager, saw this as a strategic choice for several reasons.

Skip over related stories to continue reading articleFor one thing, she said, “TTP recognized that local artists would be able to voice positive public health messages that would captivate and motivate the residents of their community.” She also saw the project as a chance to engage more with emerging artists than the organizations had in the past. “In former strategies of old systems, we would only select established artists to create projects. We are striving to position emerging artists to be included in the process of developing strategies that improve the outcome of public health crises such as COVID-19, mental health and wellness, and food injustice,” she said.

There was only one simple rule the artists would need to abide by while creating their work: messaging could not reflect public health misinformation and disinformation. The goal of their work was to inspire hope and reduce the spread of COVID. TTP staff closely monitored CDC guidelines to offer guidance in health messaging when needed. In the beginning, they emphasized the importance of handwashing and physical distancing. But as the pandemic wore on, they recognized that promoting vaccine confidence would be most beneficial in helping protect vulnerable portions of the population. But to do so, Vanessa saw the need to address deeper historical issues.

Knowing that some people in the community distrusted the country’s public health organizations and were wary of their efforts to mitigate the virus, she saw the need to distinguish TTP from those organizations, as “an arts and culture organization on the ground talking about how people felt.” “We realized there was hesitancy because of the fears communities of color have about past historical projects and experiments,” she explained. “When we thought about how to connect with the community, we knew we had to be very careful. There was a serious mistrust. Community engagement had to be pure and directed at hope and healing.”

To build that trust, TTP sought to get as many community members involved with the project as possible. Vanessa picked up the phone and started making hundreds of calls to local organizations and businesses. Everyone from bodegas, grocery stores, barbershops, and salons to mosques, churches, senior centers, and banks received a phone call. At additional individual and community Zoom calls (one of which had nearly fifty community members present), Vanessa provided the details on what TTP was and ended the call with an ask to become a part of the citywide initiative.

The project took what Vanessa called an “intentionally unconventional” approach to partnerships. Each participating business or organization was paired with an individual artist, who it had the responsibility of communicating with, supporting in the making of the work, and helping to share the work with the community once it was finished. This even applied to funding: the organizations all received a stipend from TTP, which they then used to pay the artist for their work. (The stipend was funded through grants and initiatives, including Communities for Immunity, which granted awards to museums, libraries, and cultural and tribal organizations that leveraged their roles as trusted community partners to bolster vaccine confidence in their communities.)

“Our partner organizations are pivotal to the success of this community-based initiative,” Vanessa said. “They are the support system within the artist’s circle. They are our dissemination partners and trusted connections on the ground.” She believes that facilitating these connections in the community was key to the project’s impact. “We’re building new, trusting, cross-sector relationships throughout the community that bridge the gap,” she explained. “These reliable partnerships that have been formed can be mobilized for future public health messaging support. Through these efforts, healing comes to the community, including to the artists.”

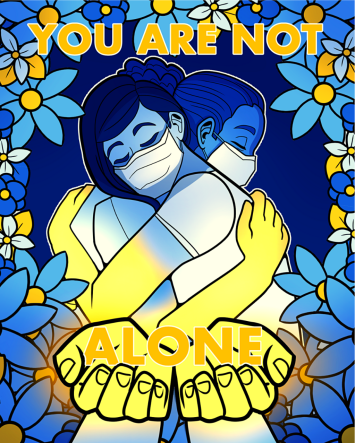

Once the artists submitted their work, TTP printed it onto posters and distributed them to partner organizations. Posters went up at after-school programs, childcare and senior centers, in the Main Street metro station, and on the walls of laundromats, liquor stores, local supermarkets, and restaurants. “Before you knew it, our posters were all over the community,” Vanessa said, “Messages of hope and healing, of, ‘You are not alone,’ of, ‘I’m happy to see you,’ of people building trust” were spreading.

Community members began requesting posters they wanted to see on their walls. Many in the local Latinx and Native American communities, for instance, asked for Gabriela Sepulevda’s work, Turtle Island Daughter, which depicted a young woman with long, loose pigtails wearing a simple orange t-shirt and a face mask made from a textile pattern. Local churches, who had put traditions like shaking hands on pause during the pandemic, often requested Mari Chavez’s work, We Will Hold Hands Again. “The churches wanted this [piece] in their foyers to spread hope about the future,” Vanessa explained: “If we get it together, do the right thing, get to a better place, we will hold hands again.” As TTP staff learned what images were most popular, they made them into postcards and stickers, which they distributed for free at community events.

As Vanessa and TTP keep an eye on the future, they continue to look at the current needs of their community. “We have found our niche because the CDC and Communities for Immunity initiative helped us find our purpose,” Vanessa said. “There may be changes, pivots, and shifts, but we have a goal of having a healthy community in the long term.”

TTP is now looking into how its local artists can impact mental health awareness, particularly among young people. “We want to make sure youth have a path to go and get the resources they need to survive the pandemic, to have a space for all the issues they are dealing with…to come out of the pandemic with a sense of belonging and purpose,” Vanessa said. “We don’t want them to lose sight of where they were and the plans they had before this.”

From watching the project unfold, Vanessa has learned that the key to creating a healthier, more resilient community is focusing on the parts that are “underutilized, under-engaged, and underappreciated,” as she believes the local emerging artists in Springfield were. “We directly improve the lives of artists by promoting their value, investing in their untapped abilities, and constructing new ways to help transform their gifts into sustainable economic development opportunities,” she said.

TTP’s work was not limited to just the visual arts, but also engaged poets, musicians, street artists, and school-aged children. For Vanessa, one of the most memorable moments of the project was speaking with one mother whose two sons wrote poetry. When the mother heard their writing in spoken word, she wept, telling Vanessa that she thought her family was handling the pandemic just fine until she heard her young son’s words:

I have been drifted apart from humankind,

six feet away from my closest friend.

Anybody could be contagious,

Everybody is a threat.

My school was once a haven

for laughing smiles, and faces.

Has been turned online.

Everyone sad with cameras turned off,

And cold embraces.

“Their honesty brought a conversation into their home that allowed the mother to be empowered about next steps,” Vanessa said. “Now she involves her kids in conversations about the health of the family and their ability to want and get the vaccine for themselves. [Before this] she never even thought the conversation was necessary to have.”

Comments