This article first appeared in the journal Exhibition (Fall 2022) Vol. 41 No. 2 and is reproduced with permission. www.name-aam.org. If you don’t read the journal, learn how you can subscribe to Exhibition to receive your copy of the full upcoming issues.

Effective exhibitions disrupt the notion that history remains locked in the past. Done right, an exhibition can make history a practical tool for justice by recovering silenced narratives and prompting audience reflection on history’s afterlives in the present. This essay explores one recent Smithsonian exhibition, Reckoning with Remembrance: History, Injustice, and the Murder of Emmett Till, to consider what it means to engage historically harmed communities in meaningful redress work. Employing “Restorative History” – a new model for museum practice grounded in the principles of restorative justice – curators and their community partners provoked audiences to confront history’s living legacies and disrupt conventional museum processes. In doing so, we examine the contours of restorative practice in its early stages of development as an approach and tackle longstanding issues in the field, such as the centering of museum authority, extractive collecting practices, and touting DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion) values without a corresponding infrastructure to support them. Restorative History works to address these shortcomings by broadening the definition of co-curation, developing radical new perspectives on mutual capacity building, and pushing the limits of redefining shared stewardship.

“Restorative History leverages the past to understand the root causes of historical harms and turns to community-based knowledge to define the best path forward.”

What is a Restorative Approach to History?

Restorative History leverages the past to understand the root causes of historical harms and turns to community-based knowledge to define the best path forward. As a brand-new theoretical approach to museum work, Restorative History builds on principles of Restorative Justice, which is the process of seeking resolution to an injustice by redressing the harm done to victims, holding offending parties accountable for their actions, and engaging the community in the meaningful resolution of that conflict. Using Restorative Justice as its foundation, Restorative History brings communities together to ask: Who has been harmed? What are their needs? And what obligations are necessary to address these needs? What sets Restorative History apart is applying the study of history to tackle a serious examination of root causes, something that the Restorative Justice community readily admits it struggles with.

As a concrete methodology, Restorative History is grounded upon a set of questions about our shared past:

- Who has been harmed?

We center communities that have experienced historical harm and exclusion.

- What are their needs?

We collaborate with communities that have experienced historical harms by the museum or historical discipline to understand their wants and needs.

- What are our institutional obligations to fulfill those needs?

We produce public history that centers the voices of communities that have experienced historical harms and make a minimum time commitment of two to three years to community-driven collaborations. This is inclusive of mutual capacity-building projects.

- What are the root causes of harm, past and present?

Using our national collections and diverse areas of expertise, we research the root causes that led to historical and contemporary harm, always uplifting local community-based scholarship and lived experience.

With a Restorative History methodology in place, a precedent for implementing this specific type of redress work at NMAH needed to be set. This began with an unexpected collecting opportunity in 2019, which became a case study for ethical collecting, interpretation, and mutual capacity building or reciprocal exchange.

Piloting Restorative Practice: The Emmett Till Marker

In the summer of 1955, a 14-year-old Black boy named Emmett Till traveled from his home in Illinois to visit relatives in Mississippi. Unfamiliar with southern Jim Crow mores, Emmett – who was known as a jokester – whistled at a white woman, Carolyn Bryant.[1] This offense was met with deadly violence at the hands of Carolyn’s husband Roy Bryant, his half-brother J. W. Milam, and likely others. Emmett was kidnapped from his bed in the middle of the night by Bryant and Milam and was subsequently beaten, mutilated, and tortured. Ultimately, his body was tied to a cotton gin to sink in the Tallahatchie River. Emmett’s mother, Mamie Till Mobley, made the brave decision to let the world see what had happened to her son. She held an open-casket funeral in Chicago which was attended in the thousands. The highly publicized lynching and the shock of the brutality inflicted on a young boy became a catalyst for the Civil Rights movement.

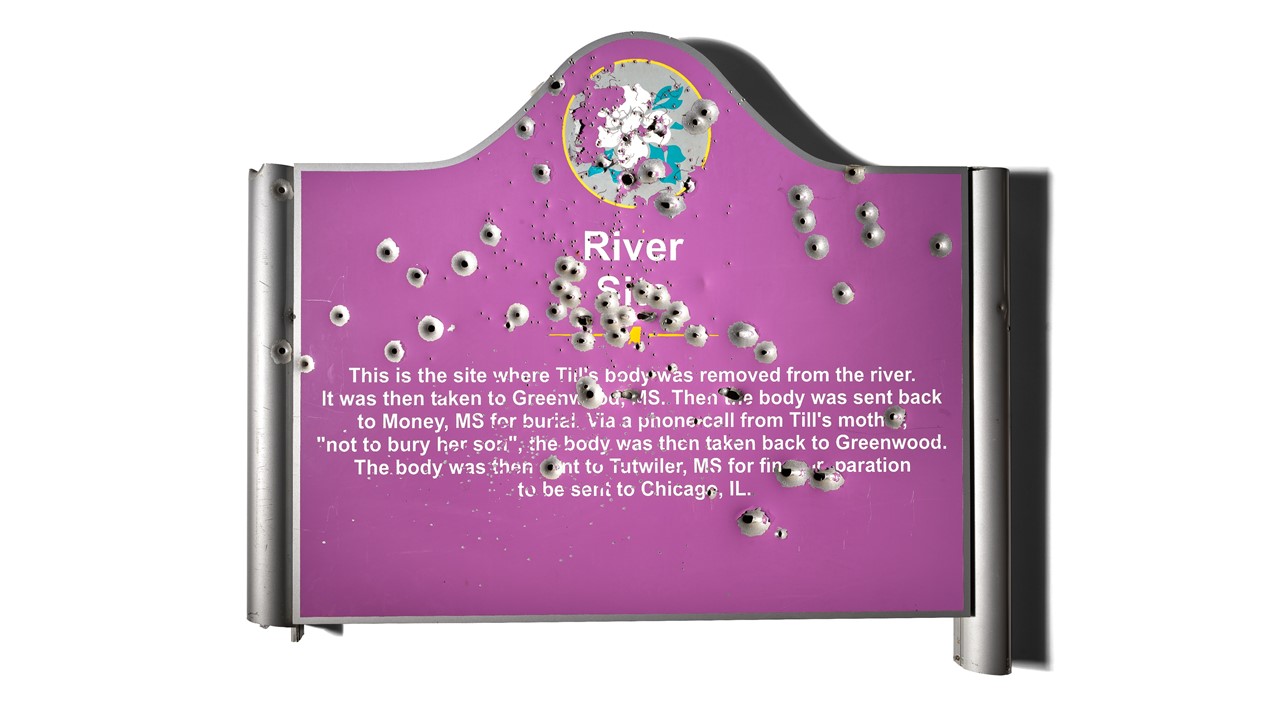

Sixty-four years later, in the summer of 2019, a shocking Instagram photo of three white University of Mississippi students went viral. The three young men stood proudly – sporting grins and rifles – in front of a bullet-ridden historical marker commemorating the lynching of Emmett Till at Graball Landing, near the Tallahatchie River. Later that fall, a security camera on the new bulletproof marker captured a white supremacist gathering at the same site. Far from a random act of vandalism, the gathering and continued destruction of the markers proved that history is an active battleground over what is remembered and what is forgotten.

“We saw this powerful object as a unique opportunity to viscerally connect the past and present of anti-Black violence for a national audience in a way that was immediate and impactful.”

The story was not new. In Mississippi, Till historical markers have a long history of being defaced: stolen, shot, hacked, doused with acid, and even thrown into the river. At the River Site alone, the historical marker has been violently attacked three times: in 2008 it was stolen and thrown in the river; in 2009 it was riddled with 317 bullets; and in 2019 it was mutilated with rifle fire. With each incident, the community of Tallahatchie County lobbied and pieced together funds to put up new markers until they finally had to install a bulletproof sign at the site. The violence against the signs eerily mimicked the violence against young Emmett Till, and for Black people in Tallahatchie County, that was no coincidence. Deep in the Mississippi Delta, Black life is precarious: cotton still dominates the landscape, segregation and poverty weigh heavy, and the main industry is Parchman Prison. Community members described that the stakes for Black history and Black life could not be higher. As the defaced historical markers made palpable, preserving Black history was quite literally a life or death issue. Stewarding Emmett Till’s memory was worth the risk.

In late 2019, NMAH Collections Specialist Luke Perez suggested that the museum consider collecting the Graball Landing marker that had made headlines. As curators of African American history focused on Restorative History practice, we agreed. We had been tracking the news ourselves and had reached out to people on the ground, which added a sense of urgency. Moreover, we saw this powerful object as a unique opportunity to viscerally connect the past and present of anti-Black violence for a national audience in a way that was immediate and impactful.

Most of the history interpreted around Emmett Till has focused on his mother’s brave decision to have an open-casket funeral in his Chicago hometown and on the impact Till’s lynching had on the Civil Rights movement. While the Graball Landing historical marker carried those histories, it also provoked contemporary reflection on the vulnerability of Black life and Black history today. Upon contacting Patrick Weems, the director of the Emmett Till Memorial Commission (EMTC), a multiracial group of citizens founded in 2006 to properly remember Emmett Till and take responsibility for their role in the injustice, Weems told us that there was a great deal more to the local story. By the 1970s, Till’s memory had been virtually erased in Tallahatchie County in both Black and white communities. Black organizers responded by putting Black history on the political docket on par with their fight for clean water, equal voting rights, and fair housing. This was because they saw Black history’s preservation as a fundamental right. Their decades of organizing culminated in the community erecting Till historical markers, planting this history onto the landscape. Inspired, we decided to travel to Mississippi and assess whether this might be the right project to pilot our Restorative History practice.

“We asked the keepers of this history if it would be ethical to remove a sensitive object from those who hold it dear, and whether there might be unintended local consequences in bringing this object into a national collection.”

Ethics of Collecting

Restorative practice prompted us to deviate from standard Smithsonian collecting practice. Typically, object donations can be brokered remotely or over a “look-see” visit that enables a curator to make a short, one- to three-day trip to assess the object(s) in person. Instead, we began with the question of whether this object should be collected. Following a redressive model that centers historical harms, we initiated a series of listening sessions throughout the state of Mississippi. We asked the keepers of this history if it would be ethical to remove a sensitive object from those who hold it dear, and whether there might be unintended local consequences in bringing this object into a national collection. Driving across the state of Mississippi into Alabama, we met with Civil Rights leaders, faculty at Historically Black Colleges and Universities, staff at state and local museums, Till family members, and stakeholders in Tallahatchie County, including the Emmett Till Memorial Commission. Diverging from typical curatorial practice, we held conversations that carried no expectations, persuasions, or promises to collect. Instead, we engaged communities adversely impacted by this violent history in identifying the harm, stating their present needs, and naming institutional obligations around the possible acquisition of the marker.

Initially, some key Black community members in Tallahatchie County did not trust NMAH to collect and interpret the sign. They worried that a large institution like ours would take the object and disengage from the community that produced and protected it. However, after another weeklong return visit and meeting virtually over a period of several months without the expectation of donation, we built trust and relationships. With the blessing of those same Black community members, the Till Commission donated a defaced River Site marker to the museum. Whether speaking with stakeholders around the state, the Emmett Till Commission, or members of the Till family, early restorative practices committed the museum to two primary obligations: 1) that NMAH exhibit the sign in the nation’s capital by foregrounding Till’s local Mississippi story and 2) that curators return to the state to amplify the decades-long work to preserve this history.

Restorative History mandates that communities are acknowledged not simply as sites of study but also as complex sites of memory and local knowledge production. To honor what the museum and the public have gained by community participants sharing their histories, it is incumbent upon the institution to share back resources, skills, and knowledge. Community partners were specifically asked how NMAH could mutually build local capacity. While government regulations prohibit the museum from offering direct financial support, we can provide other resources. Most requests have been for trainings, workshops, free services (e.g., videography, conducting oral histories, etc.), toolkits, web development/strategies, generating publications and media interest, and creating educational materials. In the case of Tallahatchie County, we began with an oral history of Jessie Jaynes Diming, a founding member of the ETMC and keeper of community history. We have since expanded to plan robust curatorial workshops and training programs for budding Black public history professionals on the frontlines of preservation work in the Delta. Guided by the questions that outline restorative practice, we work to ensure that communities have access to world-class training, materials, and consultation as they document their histories on their own terms, in their own spaces as well as at NMAH.

The alternative collecting methods, co-curation, and the mutual capacity building work that restorative practice requires are a provocation to museum practice. They require adjusting museum policies to effectively meet the community partner’s needs in ways that test an institution’s stated commitments. For us, this work required engaging members of museum leadership to justify the increased expenditures associated with these extended trips. It also required us to reorient goals to focus on relationship building and repair, even if that engagement could potentially result in no tangible “product” or collection item for the museum.

“The centerpiece and sole object was the double-sided River Site historical marker that had been defaced by 317 bullet holes.”

The Exhibition

In the fall of 2021, we put on the first exhibit piloting Restorative History methods: Reckoning with Remembrance: History, Injustice and the Murder of Emmett Till. The centerpiece and sole object was the double-sided River Site historical marker that had been defaced by 317 bullet holes. We displayed the marker and its associated interpretation prominently in Flag Hall — a large atrium space coming off the grand National Mall, offering entry to the Star-Spangled Banner exhibition (fig. 1). Co-curated with the Till Commission and members of the Till family, the exhibit was a striking yet solemn invitation to learn the local Mississippi story of the power of collective action and to unpack the ongoing contestation over Black history and its connection to anti-Black violence today. To accompany the exhibit’s opening, we also hosted a public program with the head of the Till Commission, community organizers, and surviving Till family members.

To ensure that community knowledge had primacy at the museum, we prototyped an expansive version of co-curation with our partners to provide museum audiences with direct access to the historical knowledge and expertise held by the communities that had been historically harmed by the violence of Till’s lynching. As such, at the outset of exhibit planning we asked our partners how they would like to participate, understanding that museum voices would need to be secondary to theirs. Having community participants direct the interpretation was radically new for our 175-year-old institution.

We kicked off the co-curation process by meeting with the community partners to review three sites available in the museum, each with a particular timeline for display. They unanimously agreed that the marker needed to be set apart, uncluttered by other objects or competing images to signify reverence and importance. They selected Flag Hall for the powerful messaging potential. However, the museum had not exhibited in this open-atrium area since 1998. It would require dedicated security supervision, and as prime museum rental space, each day the exhibit was up the museum would lose substantial revenue when budgets were slashed due to COVID-19. This took lobbying and support at the level of senior leadership to arrive at an understanding that a commitment to restorative work meant making hard decisions about museum priorities and budgetary ethics that align with redress – one could not come without the other.

When approaching label writing and design, we were mindful that the process of co-curation needed flexibility to accommodate preferences that could vary–from having partners participate in every step of the process to only approving the final design and/or only approving the text. Here too was a demand for a new, nimble model for NMAH where no established structures for community-based authority existed. Our Mississippi partners asked us to write the exhibit labels and webpage based upon their agreed interpretation. We reviewed script versions line by line, providing our partners with final say over three draft cycles. We shared the design in a similar manner and represented our partners’ stated interests and perspectives in design meetings at the museum. On our partners’ behalf, we pushed to ensure that several criteria were met: that the sign meet most adult audiences at eye level; that embracing walls would be fabricated to create a quiet, intentional encounter in a large, voluminous space; and that labels would foreground first-person quotes. Similarly, we worked closely with conservator Cathy Valentour, who diligently preserved each fleck of paint ripped up from the sign by the bullet blasts.

Accommodating these extra levels of review and consultation disrupted our typical tight production timeline and upended a well-established, linear exhibition process. Still, this degree of co-curation was crucial: for some Black community members in Tallahatchie County, the sign holds as much meaning as Till’s very body. To this day, the notion that the sign is akin to a grave marker informs how we continue to conserve, display, and digitally share the sacred object.

While our first obligation was to exhibit the Tallahatchie story in the national museum, as we begin the second stage of our work we find ourselves confronting the limitations of museum policy and funding for redressive practice. Our second obligation is to return to Mississippi to amplify the longstanding but overlooked work to document the state’s Black history. This challenges the museum to move beyond the commonly held belief that exhibitions are an end product—the culmination of a project or a set of relationships. In addition to programming, our partners have asked for training and assistance in creating a webpage. More challengingly, they have requested that NMAH use its connections and grant-writing experience to jumpstart a community center named for Emmett Till. The proposed center would concretely connect past injustices to present needs to address persistent structural inequalities while creating a space to revitalize community bonds through art, history, and local festivals. Finally, our partners ask that the marker return to the state; they want us to travel Reckoning with Remembrance. Each request disrupts standard museum practice, tests museum capacity, pushes timelines, strains loan procedures, and raises uncomfortable questions about where ultimate authority resides. We argue that it should.

The work of Restorative History is to provoke redressive change at all levels. By centering communities in our practices, we tackle longstanding structures of exclusion embedded in core museum practice as we broaden co-curation, offer radical new perspectives on mutual capacity building, and test the limits of redefining shared stewardship. This comes at a price: the financial costs of frequent travel as we meet face-to-face to build trust with community partners; the resources and staff time needed to engage in long-term resource exchange and mutual capacity building; and the cost overruns of co-curated exhibitions that require flexible timelines and workflows. These expenditures are worth it because they redress destructive past museum practices with harmed communities directing the scope.

With restorative practice, the budgets of large institutions like the National Museum of American History become ethical documents that dictate an organization’s willingness to follow through on the obligations required by redress work. There are difficult power shifts as well. Restorative History requires that museums cede authority to harmed communities, defer to expertise of BIPOC museum professionals regarding their areas of specialization, and address new audiences’ needs for compassionate collections care, ethical representation, and considerate monitoring of social media. Redressive practice can be especially costly for large institutions that have some of the most troublesome records for doing harm in the field, but the payoff can be transformative and lasting. It challenges museums to consider that an exhibition is not always the most important product, but rather that it can serve as a conduit to create, provoke, and test altogether new practices.

[1] Whether or not Emmett Till whistled at Carolyn Bryant is a fact disputed by historians. However, following Restorative History practice, curators privileged the knowledge Till family member, Reverend Wheeler Parker, who was an eyewitness to the event.

Comments