This article first appeared in the journal Exhibition (Fall 2022) Vol. 41 No. 2 and is reproduced with permission. www.name-aam.org. If you don’t read the journal, learn how you can subscribe to Exhibition to receive your copy of the full upcoming issues.

Think about the deserts of the Western United States…of Texas…of Mexico. You are probably forming a picture in your head right now of unbearable sun, endless dunes of sand, and that clichéd ball of tumbleweed, broken away from its roots and running astray. Tumbleweed…it seems to be an iconic representation of aridness, of solitude, of infertile ground. But perhaps we have got it all wrong.

Tumbleweed is a courageous plant. Before it starts rolling across the desert, it grows firmly and steadily on a spot that, despite seemingly adverse conditions, welcomes and nurtures that seed. Only when it is mature enough does it detach from the ground. Carried by the wind, it spreads its seeds everywhere it goes. It is only a matter of time before it becomes unstoppable and ubiquitous, defying the odds and surpassing all kinds of obstacles, and planting something new and vibrant (fig. 1).

At the heart of Ciudad Juárez, Mexico sits La Rodadora Espacio Interactivo, an interactive museum built for and by the people of this city. Rodadora is the Spanish word for tumbleweed, and the museum was named after this desert plant when it opened its doors to the public in 2013 (fig. 2).

Ciudad Juárez sits on the border between Mexico and the United States, is located in the middle of the Chihuahuan desert, is a home to 1.3 million people (most of them immigrants), and was the most violent place in the world from 2008 to 2010.[1] Back then, Ciudad Juárez was frequently in the news. The city was consumed by a wave of violence and crime,[2] and the statistics were disturbing: 30 percent of businesses closed their doors due to extortion; 86,000 jobs were lost; 14,000 children became orphans; around 300,000 inhabitants fled the city due to fear and insecurity in search of a safe haven; and in 2010 alone, 3,766 homicides were reported.[3]

Around 2009, local government officials, as well as private citizens, created an initiative called Estrategia Todos Somos Juárez to devise and implement a plan for fighting crime,[4] but even as it began to yield results, local community leaders knew it would take much more to build peace. As violence started to subside, people also needed to restore their sense of safety, to build community, and to regain pride in their hometown.

The city was in desperate need of individuals and institutions who were bold enough to do something different and to create safe spaces with the potential of igniting change. Back in 2004, Papalote Móvil (Mobile Papalote), a traveling museum that was an initiative from Papalote Children’s Museum in Mexico City, had visited Ciudad Juárez. During its four-month stay, it was visited by 213,453 people. Having seen the impact of Papalote Móvil, a museum quickly became part of the conversation. In 2009, a group of local business leaders who had created a patronage sought out our team of museum developers at Sietecolores to bring the project to fruition.

In this article, we present our approach to creating Rodadora, as well as some reflections on how it has sustained its spirit as an audacious institution that builds community during its nine years of operation.

Growing Roots: Creating the Museum

When Ciudad Juárez leaders from the private sector sought out Sietecolores with the idea of creating a museum, our team stepped up to the challenge: to design a space in the city for learning, healing, and building community. The local government provided the land inside a public park, very close to the border between Mexico and the United States, where a new building was constructed from 2009 to 2010 by a group coordinated by Mexican architect Pablo Romero.[5] Meanwhile, we started working on a diagnosis and a master plan for the museum.

For Rodadora to be the place Ciudad Juárez needed, it was very clear for us that its roots had to be grounded in no other than its people. That is why we began the project by conducting numerous interviews to detect their needs: we talked to parents, teachers, children, researchers, artists, businesspeople, and previously incarcerated people, whose opinions we sought to understand the circle of violence and its community and personal impact. All of them agreed that they needed:

- to feel that they belonged, to build an identity as Ciudad Juárez citizens;

- to have a site that acknowledged the multiculturality of the city and highlighted its diversity;

- to feel proud of their community, to celebrate Ciudad Juárez; and

- to have safe spaces for dialogue, which is a foundation of peace.

After conducting the interviews, we realized the only way to successfully develop the museum was to have the community as co-creators of the space, that is, to create a participatory museum.[6] After all, tumbleweed needs to root and grow in a place that nurtures it before it is ready to break off, bounce around in the wind, and spread its seeds. To create a truly participatory museum, we took the following actions, which we believe are key to anyone seeking to develop a true community space:

- We found well-respected community leaders and made them our allies. Identifying and reaching out to individuals who people in the community listened to and trusted was key for getting the buy-in of Ciudad Juárez citizens and gaining access to groups that would not have normally opened their doors to us, such as the Tarahumara indigenous community or rehabilitated formerly incarcerated individuals.[7]

- We reached out to a wide variety of community groups. This was a must if we wanted the museum to be a place for everyone, which was the spirit we had wanted to bring to the project. We did almost 30 interviews with 17 different groups that included parents, teachers, local leaders, youth, businesspeople, artists, researchers, and organizations, among others. Nobody could be left out of the conversation and the project.

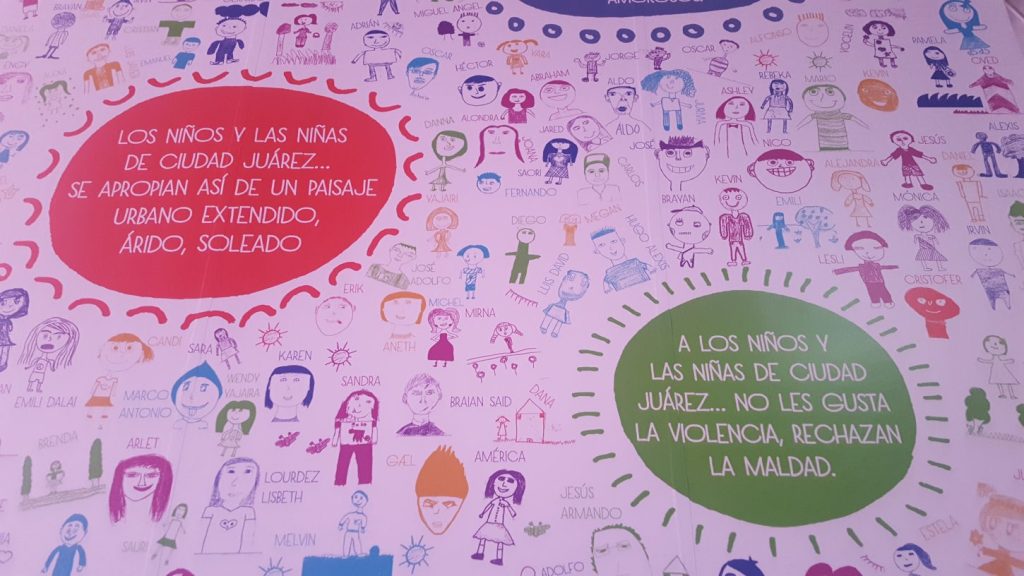

- We created spaces that invited and celebrated everyone’s voice. If the museum was going to truly belong to the community and be a safe space for dialogue, all community groups had to be reflected and be able to imprint their touch in the space. It also had to be a space created by the local community. After the diagnostic interviews, many participants agreed to work with us on projects for Rodadora, and in periodic work sessions with them, we brainstormed possible ways to get different community members involved. For example, the indigenous Tarahumara community created tumbleweed sculptures (fig. 3) for the lobby and hallways; local artist Carlos Quevedo created a giant alebrije, a colorful Mexican folk art sculpture of an imaginary creature, where visitors externalize their fears; craftsman Juan Quezada designed a mural that alludes to local pottery designs to adorn Rodadora’s library widow (fig. 4); the collective Cultura Muerta painted a graffiti mural with a vision for Ciudad Juárez, showcasing the vibrant urban art scene of the city and the work of young artists (fig. 5); and children drew their portraits and wrote their hopes and dreams for the city resulting in a wall that welcomes you to the space (fig. 6).

After four years of anticipation and hard work, Rodadora finally opened its doors in 2013 with the motto celebra la vida (celebrate life).

Rolling Across the Desert: Operating the Museum

In the nine years since it opened, Rodadora has designed many initiatives—such as exhibitions and programs—to combat a culture of violence, to invite dialogue within, and to bring together the community. The process has offered many valuable and illuminating insights, including the following:

Facing our fears. To face your fears and help someone do so, you have to first be aware of them. Artist Carlos Quevedo created an alebrije–a traditional and very well-known form of folk art in Mexico–that was affectionately called the Nightmare-Eating Monster at the museum. At this exhibit (fig. 7), titled “De dónde vienen los sueños?” (Where do dreams come from?), visitors draw or write down their fears and nightmares to “feed” them to the magical creature. When it “eats” them, they can’t haunt us anymore, or could they? This exhibit does not have the power to stop any real danger, but it can help everyone who faces it to feel a little braver, and for Rodadora, it is a thermometer of the local community’s concerns.

Analyzing the written and drawn responses, we quickly started to find some patterns: about one-third of children named violence-related situations as their worst fear. We would even see drawings of people they knew and loved holding guns. As for adults, they would often express how afraid they were that their children would become yet another victim, or how scared it made them to witness yet another fatal crime.

Based on this input, we created different initiatives. For example, during museum hours we held special short workshops in Rodadora’s library, the Rodateca, so everyone who visited had the opportunity to further expand on how to beat the power fear holds over us (fig. 8). The museum’s mediators led conversations around what the children expressed through the Nightmare-Eating Monster and what it means to face your fears. Another initiative was the performance of a play called Los Muertos (The Dead). Created by local actors, it addresses the theme of death and is now performed every November–the month in which Mexico celebrates the Day of the Dead. This play is performed after hours and is directed toward adults.

Supporting brave young leaders. Holding conversations held as part of activities like the ones described is no easy task. In charge of leading them, as well as of almost every aspect of Rodadora’s experience, are the Rodis,[8] the museum’s educational mediators. The Rodis team is made up of young people who collaborate in the museum in a six-month-long volunteer program focused on improving their employability skills as well as serving their community through the mediation of Rodadora’s educational programs for visitors. The museum periodically puts out an open call targeting local high school and college students who are required to do community service as part of the school curriculum, and who are interested in applying.

The Rodis’s initial training and mentoring program was robust to begin with; it consisted of a month-long program in which applicants got to know Rodadora, its learning framework and operational procedures; practiced mediation and communication skills; and learned about the museum’s exhibits, content, and programs. However, we soon realized that members of the Rodis had been victims of some forms of violence, too. These are extremely brave young people who often encounter difficult situations that require them to improvise. We knew we would have to work with them before they could be ready to do this and to help visitors heal. We decided we had the duty to provide a safe space for them to have these same conversations, so hand in hand with our mentoring guides who are trained psychologists and educators, Rodis explored the nature of nightmares, spoke about their greatest fears out loud—sometimes even past traumatic events—and finally, let go of them by doing exactly what the visitors do: feeding them to the alebrije.

We were witnesses to the transformation of some highly anxious and apathetic youth struggling with training and communicating with their peers to extremely sensitive and empathetic individuals. We also realized that the Rodis who had the hardest time at first turned out to be the strongest mediators of these fantastic yet difficult experiences. As new programs and activities require further training and support for our young mediators, the museum continues to be ready to provide it to them.

Reaching out to the community. Throughout this journey, we have not forgotten our roots. Rodadora continues to design programs in tandem with different sectors of the community, such as Cultivando Sueños (Cultivating Dreams) and Rally Celebra la Vida (Celebrate Life Rally).

The museum hosts tens of thousands of children who live in areas heavily affected by violence and other factors that impact their quality of life. Rally Celebra la Vida was conceptualized after extensive research determined which areas of the city were home to the highest amount of violent crime. Children from these neighborhoods would come to the museum on multiple visits to participate in a specific set of workshops and activities designed to combat the anxiety caused by their environment, increase their self-efficacy, and widen their beliefs about their professional future. Children would find a series of QR codes scattered throughout the museum, which they scanned with a tablet. Codes were placed at 60 interactive exhibits and at additional spaces, such as classrooms and the museum’s library, and invited visitors to complete challenges that connected Rodadora’s content with the development of these essential skills. At the end of the rally, children would conceptualize and design a superhero that they felt their community needed by drawing it and taking it home. Not only did this help them convey their reality much more clearly, but it gave the Rodis the tools to guide them, empowering them to become the real sidekick of their creations and use their power as their hero would have, by sharing their drawings with the group and starting reflections through dialogue.

“Codes were placed at 60 interactive exhibits and at additional spaces, such as classrooms and the museum’s library, and invited visitors to complete challenges that connected Rodadora’s content with the development of these essential skills.”

An external evaluation agency worked alongside the Rodis to document and analyze the results of the workshop. After implementing a test and conducting several focus groups with parents and teachers, we found that anxiety in participants did decrease while self-confidence increased.[9]

Spreading the Seeds: Final Thoughts

Nine years have gone by since Rodadora opened its doors, and the tumbleweed has kept on going and spreading its seeds. Upon reflection, we have some final insights about the creation and upkeep of this brave community space, since it was built to fight the once normalized wave of violence that had spread throughout the city and to foster the peaceful interaction that people in Ciudad Juárez sought (fig. 9).

We believe that museums are not responsible for solving all the problems in a community, nor are they a magic formula for doing so. However, they can have a powerful impact on the people they reach. Rodadora’s goal is to create spaces where people feel safe enough to address their problems, heal some of their wounds, come together, and take action. Life in Ciudad Juárez has not been magically fixed, but we can say that things have gotten better little by little. The fears of the community have changed as crime and violence have significantly subsided, something that has been clearly reflected in our exhibits and the dialogues we hold in the museum.

But again, there is not a single place or strategy that has accomplished this. Changing and taking care of a community is the co-responsibility of numerous parties. We see governmental agencies, private companies, and strong people work hard to make this city the place we long for. Rodadora has served—through its programs, exhibitions, and daily work—as the field where the community, the government, and private initiative have built a strong relationship.

We aim to leave a small seed from this tumbleweed in everyone we meet. We know that not every single one of them will sprout, yet whenever a Rodi or a child leaves our museum just a little braver, they carry one of these seeds, flowering new tumbleweeds that will now track their paths and inspire even more people to fight for this city, for themselves, for the brave new world they deserve. Just as the motto of Rodadora suggests, they will be “celebrating life” (intro image).[10]

[1] Sam Quinones, “Once the World’s Most Dangerous City, Juárez Returns to Life,” National Geographic (2016), https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/article/juarez-mexico-border-city-drug-cartels-murder-revival.

[2] Violence in Juárez started due to the drug war between cartels.

[3] Sam Quinones, “Once the World’s Most Dangerous City”; Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática, Estadísticas de mortalidad, Ciudad Juárez (INEGI, 2017); Plan Estratégico de Juárez, A.C., Informe Así Estamos Juárez (Plan Estratégico de Juárez, 2017).

[4] “Mesas de Seguridad,” Mesa de Seguridad y Justicia de Chihuahua, 2022, http://mesadeseguridadchihuahua.org/mesas-de-seguridad/.

[5] The total surface of the land where the museum was built was 355,209 square feet. The construction surface totaled 163,396 square feet.

[6] Nina Simon describes a participatory museum as a place where “visitors can create, share, and connect with each other around content.” See Nina Simon, The Participatory Museum (Museum 2.0, 2010), p. ii. You can read Simon’s book online at: https://www.participatorymuseum.org/read/.

[7] We sought out formerly incarcerated individuals because we wanted to understand the reasons behind the violence and crime, and gather their thoughts on what the community needed in order to change, live peacefully, and stop the cycle of violence.

[8] “Rodis” is a made-up word that we came up with for Rodadora’s docents. It is a direct reference to the museum’s name.

[9] Based on a sample of 370 participants, the t-student test proved a significant decrease (p=.036, α=0.05) in their anxiety scores (select items from Spencer Children’s Anxiety Scale and Revised Scale for Anxiety and Depression in Children) before and after engaging in the program (15.19 and 14.6 respectively). Several focus groups were conducted with this sample and other participants, including their parents and teachers. They cite an increase in their children’s self-confidence, interest in pursuing college degrees, and respectful interactions with peers after the program finished.

[10] A special thanks to Karen Álamo (Executive Director of La Rodadora Espacio Interactivo) for all the information shared for this article.

Comments