How can museums build bridges and foster tolerance to strengthen democracy?

This article originally appeared in Museum magazine’s January/February 2023 issue, a benefit of AAM membership, and is part of our annual forecasting report, TrendsWatch: Building the Post-pandemic World (March, 2023). Download your free copy of TrendsWatch.

A house divided against itself cannot stand. —Abraham Lincoln

Our country is racked by political rancor, intransigence on critical issues, and heightened tendency toward violence. This hyper-partisanship is impeding the work of public institutions, including schools and libraries, and impairing our ability to respond to threats such as pandemics and climate change. Some worry that the stability of our government is itself at risk.

To maintain a functioning democracy, we need to learn to talk across the growing political chasm, foster mutual respect, and encourage peaceful civic participation. Museums can play a role in narrowing the partisan divide, using their superpower of trust to build bridges, foster tolerance, and nurture inclusive attitudes.

The Challenge

Political polarization in the US has been growing for the past quarter century. It’s not clear to what extent this growing divide stems from fundamental disagreements on critical issues such as racial justice, climate change, and immigration policy, and to what extent these issues have become proxies for deeper disputes about culture, identity, and the role of government. We are experiencing a growing number of threats to election workers, elected or appointed officials, law enforcement, and government employees. At the height of the pandemic, researchers at Johns Hopkins University found that one in five Americans thought it was okay to threaten public health officials. So many acts of aggression have been directed at libraries and librarians that the American Library Association issued a statement condemning the trend.

These threats and actions may be symptoms of a deep and growing sense of alienation. Leading up to Independence Day last year, the University of Chicago released a report showing that nearly half of Americans feel like “a stranger in their own country,” and 28 percent of voters feel it may be necessary, sometime soon, for citizens to take up arms against the government. In a recent briefing for President Joe Biden, historians warned that democracy itself may be at risk. In the face of such dire signals, what can all of us do, as individuals and institutions, to hold things together?

Rancorous partisanship has been a defining feature of American politics even before the country achieved independence. (John Adams habitually referred to his fellow founding father Alexander Hamilton as a “bastard brat of a Scotch pedlar.”) One might argue this passion is a feature, not a bug. Throughout our history, partisan ardor has also fueled civic participation, cycling between peaks of conflict and voter turnout, and troughs of amity and low engagement.

Passions are once again on the rise. Increasingly, Republicans and Democrats not only object to the other party, but to the people in that party, viewing each other as close-minded, dishonest, immoral, and unintelligent. Is this surge in violent rhetoric (and occasionally violent acts) simply another crest in America’s historic cycle, or do current events potentially signal something worse?

In the past, the forces that divided us were diminished by day-to-day exposure to people of diverse views. But Americans increasingly politically self-segregate by where they live, where they work, who they socialize with, and who they choose to marry. Nearly half of college students don’t want to room with someone who votes differently from them. There is a growing demographic divide between urban centers and the rest of the country (leading to some Democrat-leaning cities being sued by their conservative state government for seeking to use their own funding to support abortion access).

This sorting creates barriers to conversation—and it is distressingly easy to demonize people you never meet. Making things still worse, while we are increasingly physically aggregated by ideology, we are hyper-connected on social media. These platforms foster isolated echo chambers while lowering barriers to uncivil discourse and amplifying the voices of small numbers of people with extreme views.

America’s current “pernicious polarization” (as it has been dubbed by political scientist Jennifer McCoy) may in fact be unprecedented—surpassing the political division experienced in our country or in any of our peer democracies in the past half century. And research suggests that such severe polarization could lead to serious democratic decline, at the extreme descending into some form of authoritarian regime. Where might this lead?

Polling in 2022 showed 60 percent of Americans anticipate an increase in political violence in coming years, and 43 percent think a civil war is at least somewhat likely. Some researchers and policy makers fear we may functionally fracture into two Americas—red and blue—sharing the same geographic space or, at worst, experience a second civil war.

However, in the midst of this depressing deluge of data, we can also find rays of hope. In 2022, the Strengthening Democracy Challenge showed that many kinds of interventions can significantly reduce partisan animosity and strengthen democracy. And there are some indicators we may be rebounding from partisan extremes. An increasing share of Americans identify as moderate—and a stronger middle might make for a more stable democracy. (See “Why I’m Hopeful” by Susie Wilkening on the previous page for more reasons to be optimistic.)

It is vitally important that we chart a path between apathy and violence and bridge the growing partisan divide. How might we build a new, better synthesis that combines the energy and passion of caring with open and inclusive attitudes that can help unite our country?

What This Means for Museums

Museums, as prominent symbols of civic life, can all too easily become pawns in partisan quarrels. In 1989 Senator Jesse Helms used Andres Serrano’s photograph Piss Christ as an excuse for efforts to defund the National Endowment for the Arts. In 1999, county prosecutors charged the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati, and its director, with purveying obscenity when the center hosted the Robert Mapplethorpe exhibition “The Perfect Moment.” In 1999, New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani made political hay from controversial art in the “Sensation” exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, threatening to withdraw city funding.

Unfortunately, museums and allied sectors are beginning to get caught up in a new wave of politically fueled culture wars. Some states are drafting legislation that would control how libraries build their collections and how librarians provide access to books, resources, and information, and abolish the immunity that traditionally shielded librarians for the decisions they make. In Florida, businesses (including museums) with 15 or more employees must now comply with the new Individual Freedom Act (aka the “Stop WOKE Act”) that limits how they can provide diversity, equity, accessibility, and inclusion (DEAI) training. Stories of censorship and threats of violence form a grim diary of 2022.

In March, the Idaho House of Representatives passed Bill 666, which would have deprived schools, museums, colleges, and public libraries of protections shielding them from charges of “disseminating material harmful to minors.” (The bill died in the state Senate.)

In June in North Carolina, the county manager ordered the Gaston County Museum of Art and History to remove a photograph of two men kissing—one commissioner, noting that he believes that homosexuality is a sin, said he would defund the museum given a chance.

In September, 30 or so armed members of the Proud Boys (self-described “Western chauvinists”) showed up to protest a family-friendly drag show and dance party at the Museum of Science and History in Memphis, Tennessee, forcing the museum to cancel the event.

As these examples illustrate, museums can become targets when their actions touch on issues central to political identity—and right now that is a very long list of issues.

In addition to uproars over specific exhibits, books, or statements, a broader risk arises when a sector is perceived as inherently partisan. Higher education as a whole has come under attack by conservatives concerned that college campuses (faculty and students) skew strongly liberal. Data from the Pew Research Center shows that almost three-quarters of Republicans think higher ed is “going in the wrong direction” (compared with half of Democrats), with almost 80 percent of these Republicans attributing this “wrong direction” to professors’ liberal bias. While there is no evidence that these perceptions have led to fewer Republicans sending their kids to college (yet), it may fuel the fragmentation of higher ed. Colleges and universities (like the new University of Austin) promising to create conservative campuses could deconstruct the academic melting pot that has historically exposed students to peers with different politics and values from their own.

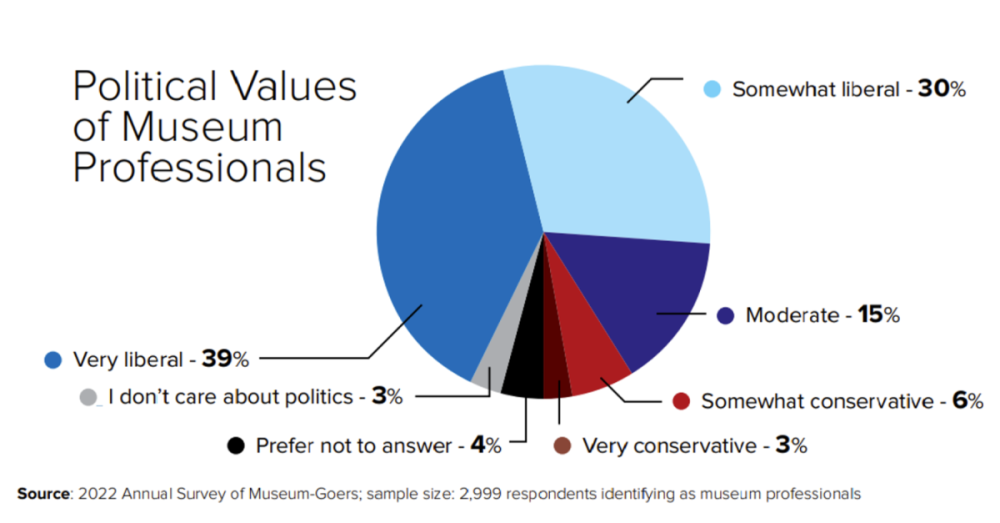

While it may be less evident to the public, the museum field also skews significantly to the left, with 69 percent of people working in the museum sector identifying as somewhat or very liberal compared to one-quarter of the public. These political differences may become relevant as museums come under pressure from inside and outside the sector to take positions on issues—whether directly related to their mission or of importance to society generally.

AAM’s Museums and Trust (2021) revealed that nearly half of the public believes museums should always be “neutral.” (While museum professionals understand museums are inherently not neutral, members of the public commonly use the term to mean “not take positions on issues.”) Only one in five feel museums can or should take positions on important issues, even if they are controversial. This poses a dilemma—museums as trusted sources of information can be powerful agents for change. However, museums that wield that power might be relegated to the status of “untrusted other.” How can museums present information, promote dialogue, and foster reflection without being perceived as partisan?

Currently, going to museums is a nonpartisan activity (liberals and conservatives are equally likely to have visited a museum in the past two years), and museums are trusted across the political spectrum. As such, museums can play an important role in bridging the partisan divide, using their existing superpower of trust to help build bridges and foster tolerance and inclusive attitudes.

Why I’m Hopeful

By Susie Wilkening, Wilkening Consulting

The partisan divide is indisputably painful to this country, and we see the divide clearly in our research among museum-goers. People’s political attitudes come with them to museums, and they deeply affect how they respond to content…especially content that we, as a society, do not yet have consensus on.

But long term, I have hope. And data from the Annual Survey of Museum-Goers has led to my hopeful outlook.

While political identities seem to be entrenched, people’s values are shifting, and shifting in remarkable ways.

Here’s what I am seeing in our work among both museum-goers and the broader population:

- Inclusive values are going mainstream. While the majority of museum-going liberals express inclusive values, the percentage of moderates expressing inclusive values increased from 34 percent to 43 percent from 2021 to 2022. And the portion of inclusive conservative museum-goers doubled from 14 percent to 29 percent. These patterns also carried over into our broader population sampling.

- Openness to climate change content has also gone mainstream. While a 55 percent majority of museum-going conservatives 60 or older fall on the “anti-green” side of the climate change attitudes spectrum, only a quarter of conservatives under 40 agree with them. And more young conservatives fall on the “green” side of the spectrum than the “anti-green” side. Again, we see these patterns carry over into our broader population sampling. Young conservatives think climate change is real, and we need to take action to mitigate the harms.

This isn’t just our data either. There has been a colossal shift in attitudes related to the LGBTQ+ community over the past 15 years or so (though there is still, admittedly, much more work to be done). Pew Research Center sees similar trends about climate change. And while the data about racial attitudes for the past couple of years is mixed depending on what is being asked, the long-term data trends on racial attitudes bend toward justice.

I don’t want to downplay the difficulty of addressing the political divide in 2023, nor do I want to downplay the harmful effects of racism and anti-climate change sentiment. It’s bad, and the effects are devastating. And if I am brutally honest, I think it is going to get worse before it gets better. As anti-inclusive and anti-green segments of the population slowly shrink, those who espouse those views are likely to become even more defensive, emotional, vocal, volatile, and—distressingly—violent. I think the 2020s will be politically awful, and there is the potential for real harm to people as a result.

But when I look at the long-term values shifts on these issues, I’m more hopeful that in the 2030s we will be able to come together more easily to deal with the immense challenges we are facing.

Museums Might …

- Become engaged with efforts such as Educating for American Democracy, iCivics and CivXNow, The History Co:Lab, or Made by Us to provide the education needed to support civic activism.

- Advocate for funding to support this work: AAM is a member of the CivXNow Coalition and supports bipartisan federal legislation that would authorize $5 billion to fund K–12 history and civics education and programs over the next five years. If passed into law and fully funded, at least $200 million annually would go to “qualified nonprofit organizations,” such as museums, through competitive grants. (As TrendsWatch went to print it was unclear whether or not this legislation would pass before the end of the 117th Congress in December or need to be reintroduced when the 118th Congress convenes in January.)

- Engage in actions likely to strengthen democratic attitudes, building on research about successful interventions. This might include educating people about how common anti-democratic attitudes, support for violence, and dehumanization are among partisan rivals. In addition, exhibitions and interpretation of art and history could dramatize the consequences of democratic collapse in other countries.

- Explicitly encompass political diversity in their commitment to DEAI, ensuring that staff with diverse political values feel able to express that identity at work. This commitment to diversity can apply to visitors as well, acknowledging that museums’ communities include people across the political spectrum.

- Provide free access to information that is being censored in other spheres.

- Give staff time off to work as poll workers in their communities, and provide paid time off to vote.

- Encourage voter participation by becoming a National Voter Registration Day Partner, engage with Independent Sector’s Nonprofit Voter Empowerment Project, and serve as a polling place.

Museum Examples

The Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Institute (which supports the corresponding presidential museum in the National Archives and Records Administration’s library system) hosts a number of bipartisan gatherings featuring a plethora of liberals and conservatives, specifically in the policy areas of national defense and education. The foundation also fosters the development of civic skills like dialogue, debate, and deep research on controversial topics through various education programs, including a national speech and debate program.

In 2021, Atlanta History Center launched a five-year democracy initiative leading up to its centennial in 2026 (which is also the nation’s 250th birthday), using its resources to explore the history of the components that make a healthy democratic system, including methods of civic engagement, widespread and informed voter participation, civil rights, and community leadership. The initiative is a core component in the History Center’s strategic plan, which affirms its purpose: “to use history to bring people together to explore new and different perspectives with the goal of strengthening our shared commitment to, and engagement in, our democratic system.”

In 2005, the Japanese American National Museum founded the National Center for the Preservation of Democracy to convene and educate people of all ages about democracy, transform attitudes, influence culture, and promote civic engagement. It is a place for dialogue about race and social justice where visitors can examine contemporary and historical frameworks, including the Asian American experience. The center explores the rights, freedoms, and enduring fragility of democracy, helping to build bridges and find common ground between people of diverse backgrounds and opinions.

Resources

Audiences and Inclusion: A Primer for Cultivating More Inclusive Attitudes Among the Public, American Alliance of Museums and Wilkening Consulting, 2021

aam-us.org/2021/02/09/audiences-and-inclusion-primer