“Put it in storage.”

“Replace it with something else.”

“Put up a new label.”

“Do nothing.”

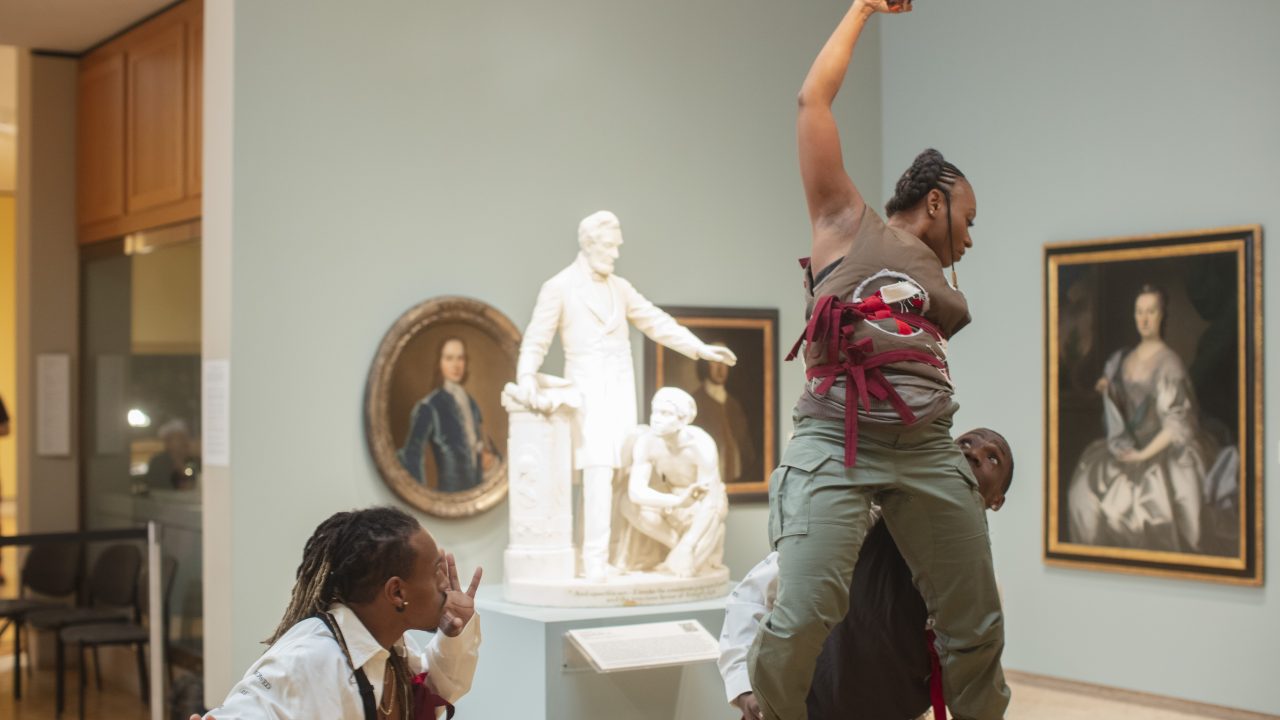

These were some of the solutions offered up when the Chazen Museum of Art at the University of Wisconsin–Madison began exploring how to confront the deeply problematic nature of an object in its collection. Thomas Ball’s Emancipation Group (1873), a half-life-size marble sculpture depicting Abraham Lincoln standing over a kneeling, newly “emancipated” person, had been on view in the museum since 1976 without contextualization or opportunity for visitor response. Like many institutions, we at the Chazen struggled with finding the “right” way to interpret the object without imposing our own inherent privilege. It wasn’t until we let go of all expectations around control and process that we realized the journey to recontextualizing Emancipation Group, in all its discomfort and vulnerability, was just as important as the outcome itself.

Finding the Right Partners

While visiting the Chazen in 2019, artist Sanford Biggers and MASK Consortium’s Mark Hines encountered Emancipation Group in the galleries. Biggers and Hines, longtime creative partners, were immediately curious about the sculpture and the museum’s plans for it as part of our broader reinstallation initiative. Thus began a conversation between Biggers, MASK Consortium, and the Chazen, which we later formalized into a project known as re:mancipation.

We couldn’t have asked for better partners to help bring perspective and expertise we knew we were lacking. Biggers’ creative practice often explores the intersection of the past and present, creating dialogues that bring American history into conversation with current social, political, and economic events. MASK Consortium is a coalition of artists and cultural institutions sharing knowledge to promote a more complete understanding of human history through the digital preservation of art and artifacts. Between Biggers’ artistic vision and MASK Consortium’s expertise in the digital realm—and their extensive shared network of creatives—we suddenly had a way to engage with Emancipation Group that aligned with the Chazen’s goals as a collaborative, forward-thinking university art museum.

We had no idea how much our partnership with Biggers and MASK would stretch the Chazen as an institution and challenge nearly every assumption we had about how museums should approach collaboration, inclusivity, and process.

Traditional Methodology with a Twist

At just over forty-five inches tall and sitting atop a prominent pedestal, Ball’s Emancipation Group occupied significant physical and emotional space in the gallery where it was on view for some forty years. Larger bronze versions of the work were erected as monuments in Washington, DC, and Boston in the 1870s, and other half-life-size marble and bronze versions are in private and public collections. Aside from this information, the museum didn’t have much documented research about the sculpture.

We knew that a comprehensive inquiry into the object’s history and iconography would therefore be necessary. Typically, this might start with a curator periodically examining the object in person, then going back to their office to get started on the research. MASK had a different process, however, which started with conducting detailed 3D scans of Emancipation Group and other related works in the permanent collection. On their first visit to the Chazen, MASK team members worked with museum staff for a week to scan nineteen objects in the collection.

To say that the 3D scanning made museum staff anxious would be an understatement. In the days leading up to the visit, feelings of skepticism and stress ran high. “Who is MASK Consortium and why are we seemingly turning the museum upside down for them?” Not only were we allowing outside collaborators full access to our spaces and collection, but we were also giving them an unprecedented level of control over the process. While we handled the objects, they curated the checklist, ran the technology, and managed the data.

The outcomes of that first visit, both tangible and intangible, far exceeded our expectations. The 3D scans MASK produced transformed how project collaborators can interact with and explore Emancipation Group. (The public can also now interact with the 3D scan.) Pulling the object out of the gallery and into a virtual realm also allowed Associate Curator of American Art Janine Yorimoto Boldt to illustrate her research in new and captivating ways. New access to the object’s history and iconography has informed exhibition planning and teacher resource development.

After working together in person for the first time, MASK team members and Chazen staff had built relationships and, most importantly, trust with one another. While there were still plenty of growing pains in our future, getting through that first milestone together made the Chazen’s staff feel more aligned with the project, even if the outcome was still ambiguous. This would become invaluable as the project evolved in size and complexity at a rapid pace.

“You said yes.”

One of the first priorities we outlined for the project was to enable others outside of the Chazen’s immediate orbit to respond to Emancipation Group. The sculpture has a powerful, visceral effect on audiences, so to only allow responses from one perspective seemed antithetical to our mission of inclusivity. But who do we invite to participate in this process, and how? Again, we offered the steering wheel to our partners and asked them to lead the way.

Through their network of creative collaborators, MASK helped to curate and document responses that were more profound, distinctive, and dynamic than we could have imagined. Interpretive dance, jazz, poetry, quilt-making, drum circles—these are just some of the many dialogues that took place with Emancipation Group in the gallery. Artists came from all over the country and collaborated with our UW–Madison colleagues. Soon, the re:mancipation network reached far beyond the gallery walls. The original group of three collaborators has now grown dramatically to include nearly a dozen artists and partners from music, dance, theater, curriculum development, film, engineering, textiles, spoken word, and more. Their responses have become part of the in-person exhibition, and many will be featured in the upcoming project documentary.

Like the 3D scanning, coordinating artistic responses was initially an overwhelming prospect to staff. We struggled with how to invite others—many of them for the first time—to come into our space on their terms, not ours. Could they bring wet art-making materials into the gallery? Probably not. Could they sew, dance, and sing? Yes, and we made it happen. Incredibly powerful moments occurred during those responses, for both Chazen staff and our collaborators, and the connections forged broadened re:mancipation’s reach even further.

In one of the early planning meetings, I asked the group why they wanted to do this with us. “You said yes,” replied Guy Routte, CEO of MASK Consortium. His response was deceptively straightforward, but that has indeed been our approach to the project. As I reflect on our experience thus far, my heart breaks a little realizing what we as a museum sector have missed over our history by not responding with “yes, and…” when opportunities arise to include voices outside our historic comfort zones.

At this point in the project, we still didn’t quite know where re:mancipation was taking us, but we knew we were on the right path.

Trust the (Uncomfortable) Process

Over the past two years, the re:mancipation project has expanded and contracted countless times. Its deliverables include everything from a documentary to teacher resource development, a symposium series, and an in-person exhibition. Many of these outcomes are being generously supported by the Mellon Foundation’s Arts and Culture grant program. The exhibition is on view at the Chazen from February 6 to June 25, 2023, and will focus equally on the historical context surrounding Emancipation Group and present-day artistic responses to the piece. Lifting the Veil, Biggers’ new work created specifically for this project, will go on view in late spring. The marble sculpture work features a standing Frederick Douglass “lifting the veil” of ignorance from a seated Lincoln. Taking inspiration from historical monuments by Charles Keck and more recent Frederick Douglass memorials, Biggers’ work also incorporates a veil made from patchwork quilts. Visitors are invited to write, draw, question, and comment as part of a documented collective response.

In line with other aspects of the project, the exhibition has inspired unprecedented collaboration among our staff. Coordinating the checklist, layout, text, loans, etc. has been an equal and steady push-and-pull between collaborators. What has kept us afloat during challenging times is the shared understanding that what we’re trying to achieve is bigger than any one temporary moment of discomfort or stress.

The exhibition is a public milestone for the project, but by no means is our work as an institution done. re:mancipation is only the beginning of the Chazen’s effort to leverage objects in its collection to work through complex issues of social justice. Our hope is that by being transparent about our process, even the difficult parts, we can inspire other museums to do the same. In comparison to the deeply painful histories that objects like Emancipation Group represent, the very least we can do as privileged institutions is accept the discomfort it might cause us to confront them.

The biggest lesson re:mancipation has taught the Chazen is that profound change cannot happen in a silo. It was only after stepping aside and trusting others to lead the way that we finally started seeing glimmers of progress within reach.

Learn more about re:mancipation at https://remancipation.org/.

Wonderful installation by an incredibly talented and far reaching team.