Storytelling in museums can be a tool of liberation.

Museums preserve things of value. People look to museums to determine what is valuable while at the same time hoping that museums will value what they treasure. This axiom at the heart of museum practice hasn’t changed. The change worth celebrating is that what—and who—museums value has expanded. We communicate that change through storytelling.

As a child, I knew that museums were special places where time could move more slowly. I treasured weekend excursions on New Jersey Transit to New York City to visit the American Museum of Natural History and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. What I didn’t treasure so much were the labels. I did not understand why museums spent valuable space relaying details about what I later came to understand as provenance. Why did the names of collectors, the materials used to make the art, and even the taxonomy of specimens get pride of place when so much was left unexplored and under-explained?

The art and artifacts in museums fired my imagination, but I often felt like I needed to sneak past the “official” narrative to get to the heart of what excited me. Who made these things, and why? Who used them, and who loved them? How did they work? Who were the people whose day-to-day lives intersected with the histories important enough to be described on gallery walls? Unless I encountered the right kind of docent, I would have to speculate.

College afforded me the opportunity to study the history of museums, and my desire to play with these spaces increased. And when I became a curator in the 2000s, change was already underway. Museums were experiencing an identity crisis at the dawn of the digital era. How could they compete with catalogues of data and sophisticated entertainment now instantly available to visitors?

Museums needed to embrace the simple reality that people were coming because they were curious, they were staying because they were empathetic, and they were returning because they were seeking authenticity. The best way for museums to signal these values was through storytelling. Art, artifacts, and collections of facts could only draw and retain a steady audience if they were wrapped in a cogent, relevant story.

The Power of Museum Storytelling

So how does storytelling free museums from the structures that held them back in the past?

- Storytelling removes limitations caused by rigid assumptions. If you assume only that your visitors are curious about the world around them, then there is no limit to the approaches you can take in connecting people with objects—and objects with their contexts.

- Storytelling pulls down the invisible barriers that sap visitor confidence and make them feel that they don’t belong in museums. Visitors are not given a chance to become bored or feel excluded when there are so many possible stories for them to encounter in a museum.

- Storytelling frees us from our silos. Science is better with history. Art is better with science. History is better with science, art, culture, and economics.

Yes, storytelling is rooted in making connections, but in museums, storytelling can do so much more than it can in more traditional narrative media, like TV, drama, and documentary, because museums are spaces of free-choice learning. Visitor experience is not bound by linear time or singular emphasis. Storytelling as the backbone of museum experiences frees curators to create new and different pathways through collections. And revealing the truth of these multiple threads and possible pathways frees visitors to experience the same museum differently every time.

At the Museum of History and Holocaust Education at Kennesaw State University in Georgia, where I am the curator, we have made this multiplicity of storytelling the centerpiece of our introductory exhibition, “Threads of Memory.” In the exhibition, we emphasize how the same artifacts can tell multiple stories depending on perspective; how the same events—in our case World War II and the Holocaust—changed every category of human endeavor, including geography, technology, culture, and politics; and how individual people encountered each other, lived through extraordinary circumstances, and emerged changed by their experiences.

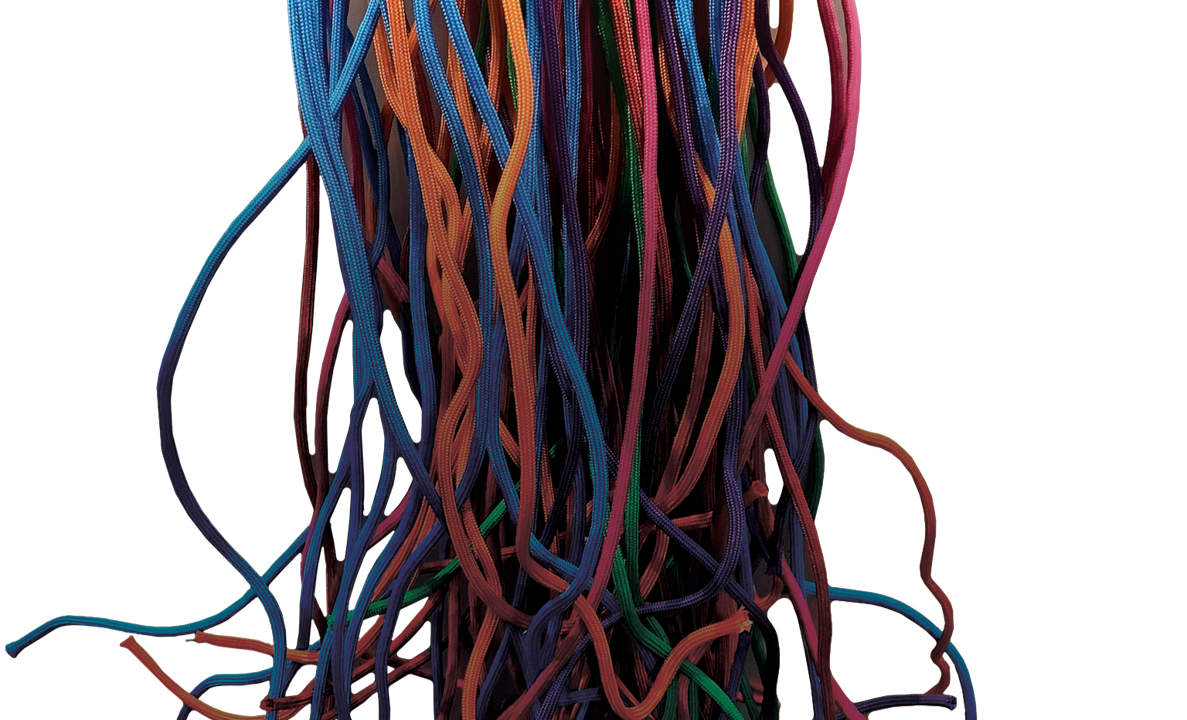

Visual metaphors, including colored threads, guide visitors along this conceptual journey. They are encouraged to pick up “thread cards” that illuminate exploration opportunities in the museum (and on the web) based on their unique interests. The exhibition culminates in an art and poetry installation (yes, art in a history museum!) based on the concept of “transformation.” Ceramicist Brad Dalton and poet Katlyn Dalton created a set of glazed jars that represent the lives of seven individuals, more and less famous, who were forever altered by the events of World War II and the Holocaust. Visitors are invited to reflect on the effects of this pivotal historical period on the threads that came together to form their own lives, and the way their own lives can, and will, affect the world around them.

Visual metaphors, including colored threads, guide visitors along this conceptual journey. They are encouraged to pick up “thread cards” that illuminate exploration opportunities in the museum (and on the web) based on their unique interests. The exhibition culminates in an art and poetry installation (yes, art in a history museum!) based on the concept of “transformation.” Ceramicist Brad Dalton and poet Katlyn Dalton created a set of glazed jars that represent the lives of seven individuals, more and less famous, who were forever altered by the events of World War II and the Holocaust. Visitors are invited to reflect on the effects of this pivotal historical period on the threads that came together to form their own lives, and the way their own lives can, and will, affect the world around them.

Used with purpose and care, storytelling in museums can be a tool of liberation. For some, the metanarratives of connoisseurship and taxonomy will continue to animate interest. What kid hasn’t wanted to collect something and share what they collected? For others, the invitation comes from wonder and shared humanity, from encountering the unexpected amid the ordinary.

As museum professionals, we have the opportunity to provide a multiplicity of pathways through the treasures entrusted to our care. In this way, stewardship and storytelling go hand in hand.

Three-Label Artifact Cases

The same artifacts can tell multiple stories, and six three-label artifact cases in the “Threads of Memory” exhibition emphasize that point. Each label tries to live up to the standards Beverly Serrell offers in Exhibit Labels: An Interpretive Approach, including a clear “big idea” and direct references to the objects on display.

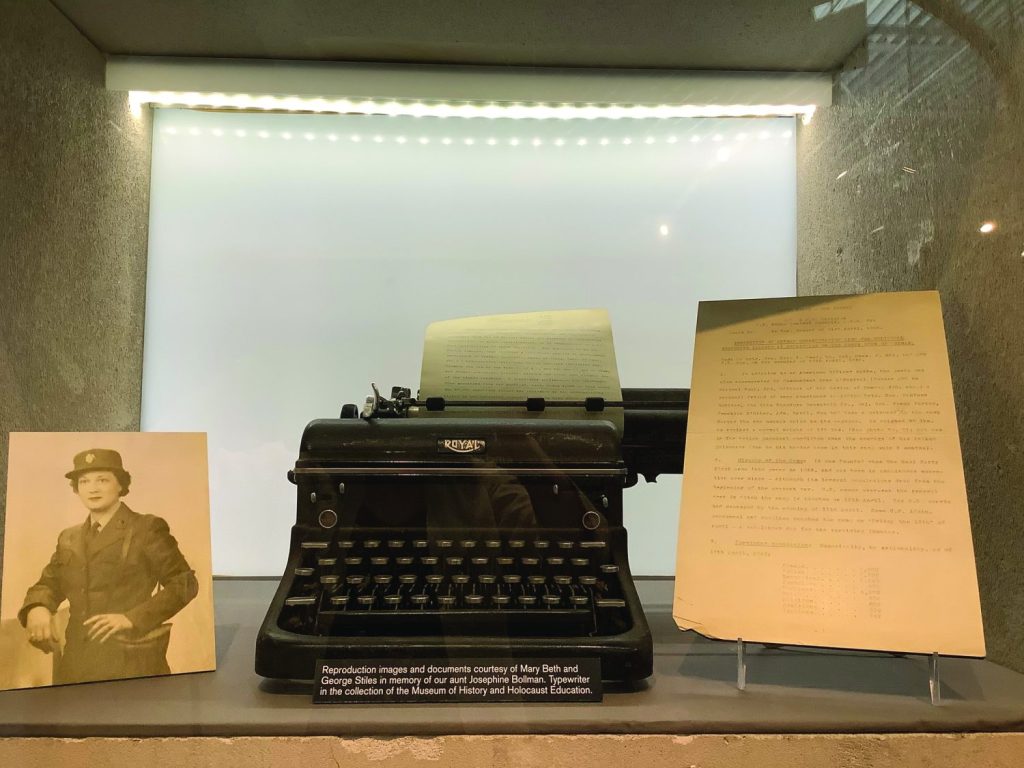

This collection of a portrait of a member of the Women’s Army Corps (WAC), a typewriter, and typewritten pages in the exhibition have the following labels:

Portrait of a WAC. Sergeant Josephine Bollman appears confident and serene in her military uniform. Although her expression might be at odds with the harsh realities of the Second World War, it illustrates the pride and competence with which more than 350,000 women served in the United States military. More women took part in World War II than in any previous war in American history. Bollman, who was born in Colonie, New York, in 1913, joined the Women’s Army Corps in January 1943. Stationed in Reims, France, she served in General Eisenhower’s communications staff.

Tactical typewriters. Perhaps more than men or arms, wars need coordinated communication to succeed. Military clerks, like Bollman, used typewriters, a late-19th century innovation, to communicate during the war. The American government encouraged people to donate typing machines like this one to war agencies in need. Wartime communication also relied on new innovations, such as radio relay, to send messages quickly across great distances.

First draft of history. Five days after inspecting the Buchenwald Concentration Camp on April 16, 1945, Brigadier General Eric Wood, Lt. Colonel Chase H. Ott and CFO S.M. Dye dictated a report about their experience. The typed pages of their report, seen here in reproduction, remained in Bollman’s personal collection of documents related to her wartime service. Reports like this one helped corroborate witness testimony during the Nuremberg Trials and enable us to understand and characterize the true horrors of the Holocaust.