Earlier this year, I presented at MuseumNext’s Museums, Health, and Wellbeing Summit about what we risk by not integrating trauma-informed practices and values into our work. In my talk, I chose to use reflective prompts and storytelling to bring those attending along for a journey, not only to spark potential points of resonance but to help them feel on a somatic level why trauma-informed practices are so critical.

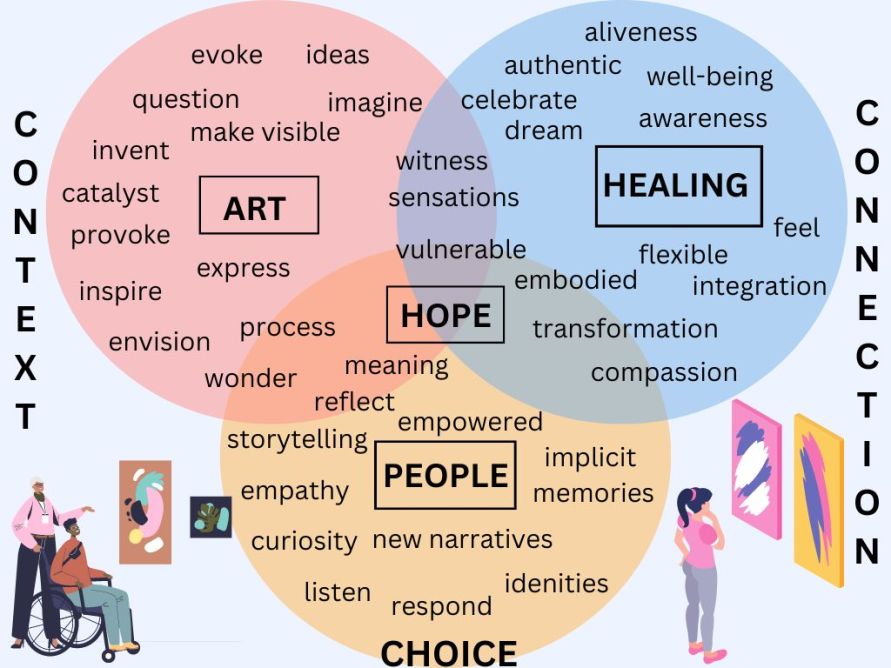

As a central arc in my presentation, I leaned on the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, as a time of collective trauma that many people still have a sense of in their bodies. If you think about those early months, we all experienced ruptures in the things all nervous systems crave to feel settled and safe: context, choice, and connection. None of us had a clear context for what was happening, as information about the virus was often conflicting, sporadic, or incomplete. Because of this, many of the choices we had in our day-to-day lives were reduced, particularly during shelter-in-place orders. And all of this impacted our sense of connection, minimizing our in-person interactions and creating a sense of heightened alertness and fear when we did come into contact with other people. Think of the times when you might have had to go out for necessities, or even to work in a job that required you to be around people every day. How did that feel in your body? How was it different from what those interactions felt like pre-COVID?

For me, getting people to notice this COVID-related activation within themselves helped create a bridge of understanding. For several years prior to the pandemic, I had been trying to advocate for the importance of trauma-informed practices in museums, but was often met with skepticism, confusion, and even disdain. As someone who experienced severe and ongoing trauma for many years, as well as the lingering impacts afterwards, the need for trauma-informed practices was always obvious. (Once you see trauma, you can’t unsee it.) But for those who hadn’t had this experience, the idea felt abstract, until they suddenly felt what it was like to lack context, choice, and connection themselves. Now that more people can understand how these things impact nervous system regulation, the question is: How can museums use this information to better support visitor and staff experiences?

What is trauma?

The definition of trauma I often use is one from Peter Levine, the developer of the Somatic Experiencing technique: anything that is too much, too soon, and too fast for our nervous system to handle, where there isn’t time or space to process the experience. Trauma is also too much for too long, where our nervous system doesn’t get a chance to settle and feels constantly under threat. On the other hand, it can also be what didn’t happen, like not having someone attuned to you or receiving the care and support you needed. There are many kinds of trauma, and many ways people respond to it.

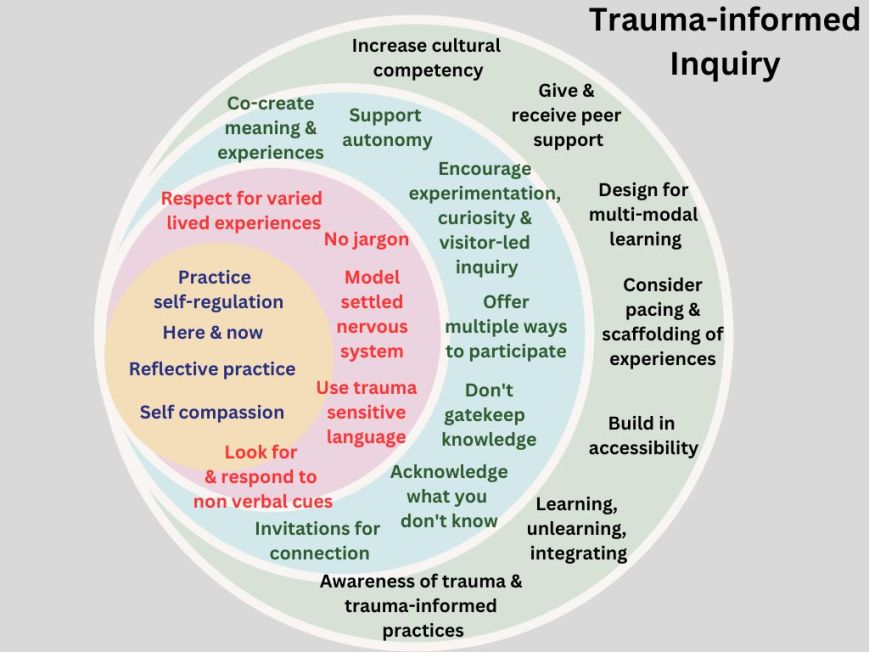

Because of this, different mental health organizations and practitioners define trauma-informed principles and values in different ways, but I prefer those outlined by clinical psychologist Dr. Karen Treisman, because I believe they are the most nuanced and best-suited for museums and other cultural organizations. Dr. Treisman defines trauma-informed principles and values as:

- Multi-layered safety and trust

- Choice, voice, agency, and empowerment

- Collaboration, communication, and transparency

- Relational, relationship focused, and humanized

- Curious, empathetic, understanding, kind, reflective, and compassionate

- Seeing behavior as communication and being curious about it

- Considering cultural humility and responsiveness

- Integrating and connecting people, ideas, systems, and the brain

In the past, I’ve often focused on the things we lose by neglecting these values, but lately I’ve begun to think more about the things we can gain from integrating them into our work. By adopting these values, we stand to gain a stronger sense of shared humanity, the foundation of relationships among staff and with the broader public that can help our field to flourish.

In thinking about how we can embrace these trauma-informed values in our work, I’ve identified three areas of focus I believe are worth prioritizing:

- Embracing vulnerability and authenticity

- Slowing down and rejecting urgency

- Centering accessibility and disability

Here’s what I mean by each of those:

#1: Embracing vulnerability and authenticity

To me, authentic vulnerability is not a performative demonstration, where you put yourself so far out there that you risk getting hurt. Rather, it is a type of steady attention which moves us into deeper engagement with ourselves and others, so that we can feel into other people’s experiences without making assumptions—a kind of sociocultural attunement. When we are radically vulnerable, we are able to recognize and address our mistakes and transgressions with compassion, helping us be accountable for righting wrongs and making changes. We are willing to acknowledge what we don’t know and to give up notions of control, gate-keeping, and all-knowingness. We learn to set shame aside because it holds us back from doing better.

However, this ability to be vulnerable and authentic is a privilege, and is more difficult for some than others. People who are traumatized, for example, might not feel safe to show up as themselves in every situation, or may experience a fragmented sense of self that makes it hard to know what that would even look like. People who are subject to systems of oppression, such as racism, ableism, and sexism, may feel pressure to mask or code-switch to avoid discrimination. To allow for vulnerability, you need to create spaces which can help people’s nervous systems settle, so they can begin to cultivate healing attention and build connections.

I’ve seen the power of building such a space myself, as I’ve worked to advocate for trauma-informed practices in museums. When I first led a training on the topic for the department I work in, I was moved by the outpouring of positive responses from my colleagues, particularly the sense that people felt more seen and connected to one another after the discussion. Getting to this point has been a long process of working through my own trauma and learning to allow myself to be seen and heard. And it’s this vulnerability that has helped me to connect with others in ways I hadn’t been able to before. For example, in writing about this topic I have been fortunate to connect virtually with colleagues from other museums and institutions who also care deeply about it.

I often think, what if the places we lived and worked in created more of these spaces for vulnerability? What if we all supported one another in our vulnerabilities, thinking of them not as weaknesses but ways forward, enhancing both the work we do and our relationships with one another? If people in positions of power in museums expressed vulnerability, would it make it safer for the rest of us? What about people in more public-facing roles, or the artists and other collaborators we work with?

I know vulnerability is a risk, and it’s never something that should be forced or expected, but I do think it can lead to more authentic interactions, stronger connections, an increased sense of belonging, and a greater sense of presence in one’s body.

#2: Slowing down and rejecting urgency

In museum work, no one will die if we slow down. Nevertheless, there’s often a misplaced sense of urgency in our day-to-day work, a busyness that isn’t helpful, and in some cases can be hurtful. When we operate as though everything is urgent, we are communicating that nothing is. Urgency can make us less flexible, less reflective, less creative, and less collaborative. It can cause us to feel stuck and closed off to new ideas, more prone to making careless errors, miscommunicating, and creating patterns and processes that are reactive rather than proactive. In addition to affecting our quality of work, it can also affect our quality of life. A sense of urgency can live in our bodies, contributing to illness and burnout. Slowing down, in contrast, enriches our work, helps us work better together, gives us space to breathe, and can counterintuitively save time in the long run, leading to a faster and smoother path forward.

At the museum where I work, MoMA, we practice this very intentionally with our Slow Looking program, which is part of a broader Artful Practices for Well-Being initiative. Since the program is all about encouraging participants to slow down, we figure it would be hypocritical if we didn’t practice the same as an education team. So, rather than doing a program each month, we commit to just three per year, to give plenty of time to be intentional about all aspects of planning, including the way the team works together behind the scenes. It’s not just about what participants see and hear but what they feel, and survey feedback indicates that Slow Looking participants pick up on how the team works to holds space for each other. They can feel the trauma-informed framework of the program, even though we don’t explicitly mention it anywhere.

Not everyone sees the benefit of slowing down at first, so sometimes committing to it as a practice means having to advocate for its value. Occasionally when I work with colleagues who are not familiar with trauma-informed principles, or may feel caught up in institutional urgency, I find myself having to set boundaries and be clear about the values and goals I’m holding in mind for a particular project. For example, one of these goals is to connect and nurture relationships, which requires being flexible and tailoring a timeline so that it makes sense for someone’s process and wellbeing. I give as much or as little support and structure as someone needs, knowing that everyone has a different way of working. People should always come first, and taking time is always worth it.

For people who have experienced trauma, both slowing down and speeding up can feel threatening in their own ways. However, urgency tends to do more harm in the long run, replicating the chaotic and overwhelming sensations of trauma, whereas slowing down, once you get through the discomfort, allows for greater space to feel, think, reflect, and respond. When institutional processes or timelines are unnecessarily rushed, they can unintentionally stir reminders or cause re-enactments of trauma, in the form of sensations, behaviors, and emotions.

#3: Centering accessibility and disability

While museums have worked to become more accessible over the years, and it’s important to acknowledge all the great work people are doing and have done, I also want us to acknowledge that as a field we could and should do better. When it comes to time and resources, I’d rather see museums cut back on the number of exhibitions or programs they produce each year than put off integrating accessibility into all our work.

This may sound extreme, if you think of disability as an issue that only affects a small portion of the public, but the facts don’t support that perception. The World Health Organization estimates that one in six people globally has a disability, while the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that one in four people in the United States does. The vast majority of these disabilities (96 percent, according to some estimates) are non-apparent conditions, like lupus, Crohn’s, rheumatoid arthritis, autism, PTSD, epilepsy, or ADHD. As awareness grows about these non-apparent disabilities, we’re learning that significantly more of our staff and visitors may benefit from accessibility initiatives than we realize.

The pandemic was a turning point for this awareness, as it led organizations to embrace practices that people with disabilities had long asked for. For the public, this meant an increase in online programming they could engage with from wherever was comfortable, with the added benefits of accessible platform features and asynchronous offerings. For staff, it (sometimes) meant more flexibility with when and where they worked, and the chance to demonstrate that their work did not suffer for it. While this period of time was not universally more accessible to all, particularly those who lacked the technology for online participation, it did create significant improvements for many.

Personally, I was surprised to find that working from home, as difficult as it was in some ways, left me feeling healthier and more rested in mind and body than working on-site. Last year, I began to make sense of why this was, when I received confirmation through a formal assessment process that I’m autistic. Looking back now, I realize that the difference with working from home was that I was able to unmask. (Masking is the action of consciously and unconsciously suppressing one’s identity in order to fit into neurotypical spaces.) Unmasking meant that I had less fatigue and burnout, and didn’t experience the emotional meltdowns I would have at the end of each workday once I got home from the office. In virtual meetings, I could use grounding tools and self-soothing behaviors without the stress of being seen, and use the chat function to share thoughts and information when jumping in verbally felt impossible. I also welcomed doing virtual presentations, because they tended to be more structured and I could have the notes I scripted up on the screen.

Embedding trauma-informed practices and values into museum cultures would mean taking needs like these into consideration in everything we do, to create experiences where everyone feels considered. And just as with universal design, where consideration for disabilities creates a better user experience for all, this work would benefit everyone, as we all have nervous systems that need support. Rather than the current standard of making “accommodations” that require special requests, it would mean thinking of accessibility as a basic human need built into the experience.

For example, those of us who work in museums don’t always realize how overwhelming and even unsafe a visit to a museum can feel for some people. There are many people, both children and adults, who would benefit from feeling more resourced in advance of a visit, such as those with autism, sensory processing disorder, social anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, or dissociative disorders. For those who have apprehensions about how their experience will go, a resource like a social narrative that clearly lays out what to expect and gently supports an in-person visit can make a lot of difference.

Concluding thoughts

In 2023, I sometimes feel as though we are trying to move forward with the emergency brake on. Many of us are experiencing cognitive dissonance and dissociation, as we try to take in all that has happened in the last few years and envision our future, which looks murkier than ever. As trauma specialist Carolyn Spring has written, “In the moment of trauma, our back brains get us fixed merely on surviving, not thinking or feeling or remembering. Afterwards, dissociative denial helps us continue to push it out of mind, so we can keep on surviving.”

I believe the only way forward is together, doing all that we can to support one another, ease each other’s burdens, help each other access the resources and time to grow, and invite in fun and playfulness (something adults often forget to do). Trauma-informed values will guide us along the way, teaching us to slow down, center humanity, and work with compassionate intentionality so that no one feels left out.

Interesting how many of your ideas overlap with creative inquiry process (7 C’s).

Claudia Cornett

This is an amazing concept.