One of AAM’s core values is to “seek and embrace a diversity of people and perspectives to enhance our work.” For me, in directing the work of the Center for the Future of Museums, that means honoring the perspectives that various cultures and traditions bring to futures thinking. The western, academic practice that guides my work regards time as linear and focuses on the practical actions individuals and businesses can take to shape the future. But there are other ways to think about time, and other benefits to imagining futures. In recent months I’ve featured guest posts that touch on Afrofuturism and Indigenous Futurism. In today’s post, Jadira Gurule, Art Museum and Visual Arts Program Manager at the National Hispanic Cultural Center, tells us about an exhibition that incorporates these practices as well as Chicana/Latinxfuturism. Taken together, these posts only begin to scratch the surface of these rich traditions of futures thinking. Please reach out to me if you can add to this conversation.

–Elizabeth Merritt, VP Strategic Foresight and Founding Director, Center for the Future of Museums.

Visions of the future created by and centering the experiences of Black, Indigenous, and other people of color (BIPOC) are essential to our collective potential to transform the world as we know it. For decades, BIPOC artists working in genres like Afrofuturism, Indigenous Futurism, and Chicana/Latinxfuturism have drawn inspiration from speculative and science fiction to make work that incorporates often excluded or overlooked perspectives into how we imagine the relationship between our pasts, presents, and futures.

This was the focus of a recent exhibition at the Art Museum at the National Hispanic Cultural Center (NHCC) in Albuquerque, New Mexico. (The NHCC is a multidisciplinary cultural center, and the Art Museum presents exhibitions on a range of subject matter by artists who identify as New Mexican, Hispanic, Chicana/o/x, Latina/o/x/e, Latin American, and Indigenous, which often focus on topics that reveal the complex intersections of creative expression and identity.) Fronteras del Futuro: Art in New Mexico and Beyond (March 2022-March 2023) featured works by thirty-one artists who have made significant contributions to Chicana/Latinxfuturism and to the art world in general.

The process of curating the exhibition and getting to know the artists has deepened my appreciation of speculative fiction. Below are just a few examples that inspire me to continue investigating the ways Chicana/Latinxfuturism are powerful liberatory tools that hold space for social and political critique and ask us to question our assumptions about the world as we know it.

Chicana/Latinxfuturism in New Mexico

The term Chicanafuturism (I also use Latinxfuturism and other terms) was coined by Catherine S. Ramírez, Professor & Chair of Latin American and Latino Studies at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Chicanafuturism investigates the production of artists who question colonialism; hierarchies of race, gender, ability, and class; the role of technology and science in our world; and more.

In organizing the exhibition, one of my areas of interest was to explore the futurist perspectives of artists with ties to New Mexico, and I was delighted to learn that the work of Española-based artist Marion Martinez was influential in the development of Ramírez’s concept of Chicanafuturism. Martinez is a “Mixed Tech Media” artist who harvests old technology for its inner beauty, reshaping circuit boards, multicolored wire, and fractured CDs to pay homage to the cultural iconography and santero traditions of New Mexico.

Another New-Mexico-based artist and curator, Augustine Romero, examines historical and contemporary topics and investigates the continued impacts of settler colonialism. In addition to his “Gutter Drones” constructed of wood, spray paint, and skateboard wheels, the exhibition featured the sculpture Languages I Used to Speak (1998), which addresses systematic processes of colonization that have led to the loss of many cultural traditions in New Mexico and elsewhere, including language.

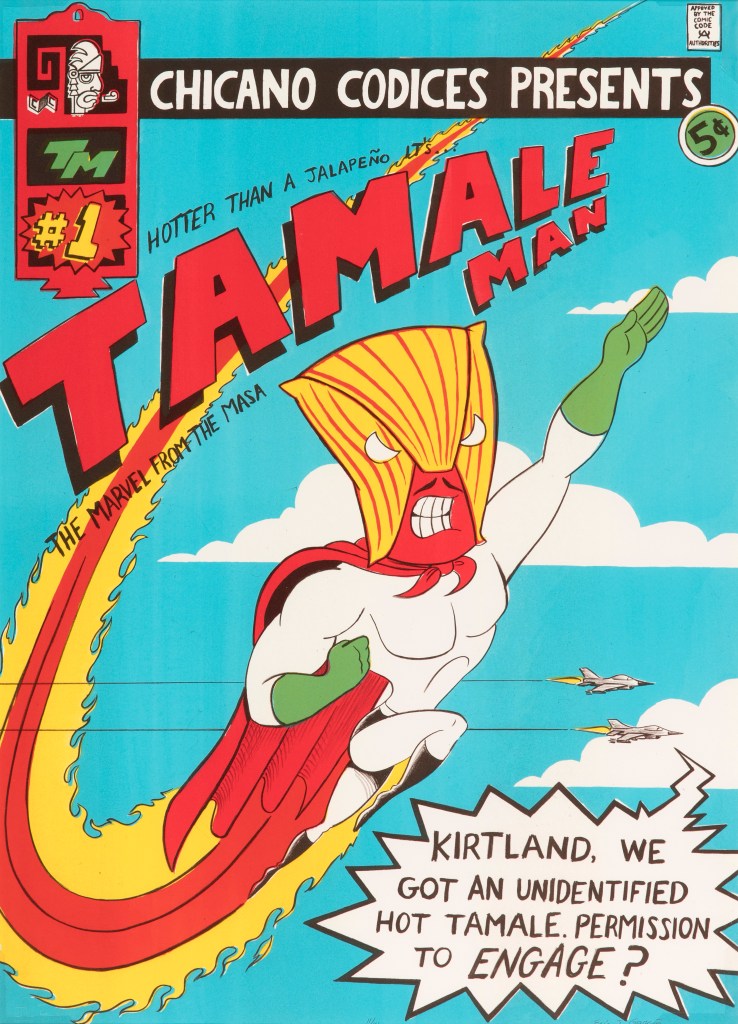

The artist Eric J. García grew up in Albuquerque’s South Valley. He addresses the lack of Latino superheroes through his character Tamale Man. At first glance, Tamale Man is a playful combination of a man, a culturally specific food, and superpowers. But a peek into the superhero’s backstory reveals that García is telling a complex story about New Mexico as the testing site for the first atomic bomb.

Not all artists engaging with science and technology in their work identify as Chicana/Latinxfuturists, yet their work contributes to this discourse in a way that can change the way we see the past, present, and future of the places and spaces we inhabit.

Interconnected Futures

Much like our identities, where lines between culture and heritage are not easily drawn, the artistic production of Chicana/o/x and Latina/o/x/e artists doesn’t exist in a vacuum, and Chicana/Latinxfuturism, Indigenous Futurism, and Afrofuturism are related in a number of ways. Fronteras del Futuro was also about these relationships and troubling dominant narratives about identity and history.

For example, Nikesha Breeze’s collaborative performance piece, Stages of Tectonic Blackness: BLACKDOM (2021), explores reconnecting with the land of an early 1900s Black settlement in New Mexico called Blackdom. The piece calls upon this history to show the power of building spaces for community to thrive. Importantly, given that New Mexico is often discussed as being tri-cultural (Indigenous, Hispanic, and Anglo), the piece reminds us that African American communities have historical roots in the state as well.

The groundbreaking novelist Octavia Butler (1947-2006), a significant contributor to Afrofuturist thought, was also throughline for exploring interconnected futurisms. Several artists in the exhibition who identify as Hispanic and Chicanx cited her literature as an inspiring force for their work, and two of the artists, Nikesha Breeze and Tigre Mashaal-Lively (1985-2022), even affectionately describe Butler as the “Founding GrandMother” of their Santa-Fe-based nonprofit Earthseed Black Arts Alliance, for her efforts to build collaborative Afrofuturist, Indigenous Futurist, and Chicanafuturist spaces.

Building for the Future

Ehren Kee Natay is a Santa-Fe-based artist and member of the Diné Nation. In his work Listening (2018), he imagines travelling through time to meet his grandfather who passed before he was born. He speaks about his work in a way that calls us to look to the past in order to heal trauma and build a path to the future. Natay’s message has personal and communal resonance, but it also has institutional importance. Museums are steeped in colonial logics, and it’s important to understand how that informs our work. What harmful systems do we participate in upholding? For what do we need to take accountability? On the contrary, what are we doing really well, and what do we want to carry forward?

Rachel Muldez’s rock sculpture Orion-Cygnus (2021) uses natural matter from this planet to provide a map of the cosmos. Meditation is key to Muldez’s practice, as she goes for long walks collecting bits of nature to create her sculptures. Orion Cygnus imagines a future where we may need to find a new home, or at least friends in other worlds. Her work reminds me that the museum can be a space to slow down, to look inward through meditation, and to connect with the stories and experiences of those around us. How can curators and educators find new ways to work together to build museum experiences that nurture introspection and connection?

Tigre Mashaal-Lively’s triptych Tricksters Folly (2020) explores mental health and transformation through folklore, depicting multiple half-human, half-animal figures who appear to be mid-transformation. Lively’s work holds space for imagining the liberatory and healing power of being in transition, in process, and in the midst of shapeshifting into a new form. It reminds me that growth and transformation can be difficult, clumsy, and sometimes painful. But there is also beauty in these liminal spaces that might encourage us to pursue thoughtful risk-taking in service of creating spaces for personal and collective transformation.

Collectively, these artists call us to the earnest work of dreaming and remind us that representation matters. Their creative labor opens gateways to reckon with our histories and envision a future where all can thrive.