In 2020, after a fifteen-year run working in museums on digital engagement projects, I decided to start my own consultancy. In the process of building it, I often heard from people familiar with my projects, whether from my blog, social media feed, or conference presentations. They shared how initiatives I had worked on in my most recent job, as the Associate Director of Digital Learning at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), still inspired them in their own work. They had questions they wanted to ask about them: How did we manage to bring so much innovation in digital design into the museum? How did we create the space to allow us to iterate in such a public way? How did we meaningfully include youth as co-designers?

Based on this curiosity, I started to get the idea that I could write a book sharing some of the best practices that had guided our work. Luckily, it had been well-documented, between more than 350 blog posts I had written detailing our efforts and the archives of meeting notes, design documents, curricular plans, presentation slides, video documentation, and research and evaluation data I had access to. Taken together, I felt like I had all the research needed to spin the tales that needed to be told.

As it turned out, the process of writing this book—Making Dinosaurs Dance: A Toolkit for Digital Design in Museums—would become a good lesson itself in the project design principles I was trying to impart. It did not magically come together in a flash of insight because I had a great idea and then everything fell into place. I developed it in part by workshopping it at museum conferences, writing a sample chapter for the proposal to validate if the idea had any merit, and eventually rewriting that chapter and the entire proposal when it was not accepted by the AAM Press the first time. Writing the book required me to believe in the value of my ideas and my ability to express them, act boldly, respond to setbacks, and be open to receiving critical feedback throughout. This way of approaching a project is exactly what I wanted to share with others.

One of the biggest benefits of going through this process was how it helped me refine and distill my thinking. Only after receiving feedback on my original proposal was I able to articulate some of the key lessons the book shares. Thanks to this iterative process, I eventually defined a set of six distinct practices we consistently sought to apply at AMNH regardless of the project, which became what I call in the book the Six Tools for Digital Design:

- User research

- Rapid prototyping

- Public piloting

- Iterative design

- Youth collaboration

- Teaming up

Here’s a little more on each tool:

1. User research: working to define and understand end-users (on the cheap)

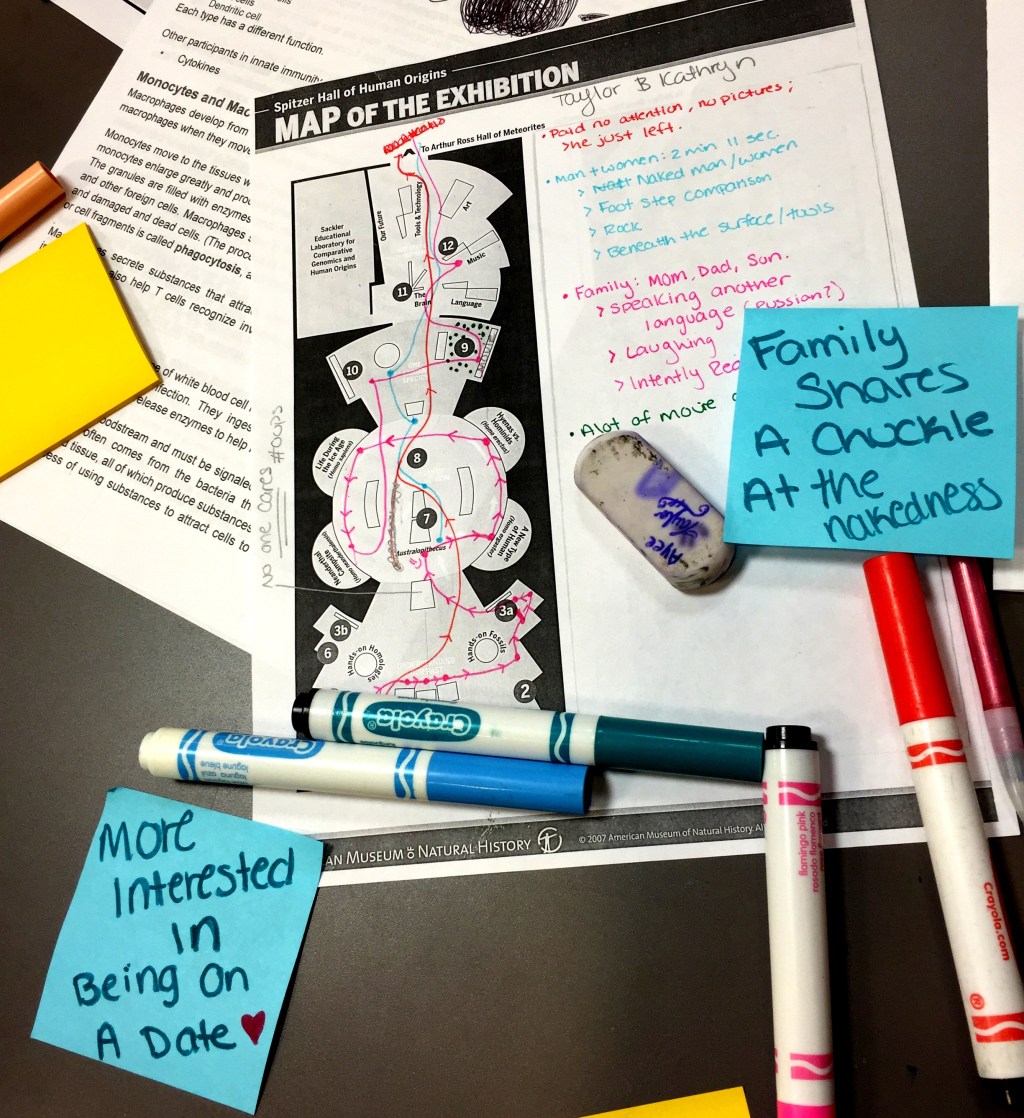

Rather than securing funds, hiring an outsider evaluator, and waiting four to eight months for a report, there were all sorts of “quick and dirty” ways we discovered to learn valuable information about the needs and challenges of our visitors within just a few days. There were readily accessible artifacts we could analyze, like photos and comments posted on social media tagged to the museum. We could take a map down to a hall, trace routes followed by ten sets of visitors passing through, then analyze the heat map that would be produced. We could quickly write and print pre- and post-survey instruments, grab clipboards, then head down in a team to interview visitors passing through an exhibit of interest.

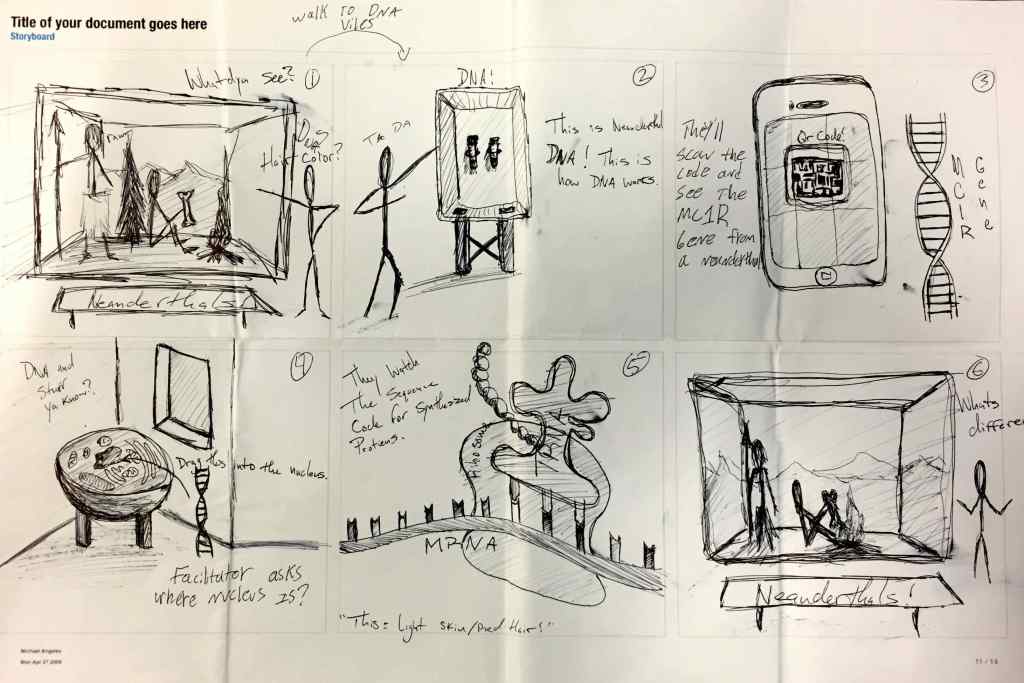

2. Rapid prototyping: putting ideas into practice as soon as possible

As soon as we had an idea of what digital experience we might want to design, we would build something—often something physical—to get it out of our heads and into the world as an object to be tested and considered. These were not early versions of the final product but ways to answer key questions: Will visitors find the topic engaging? Can this be integrated into the overall exhibition experience? How will people stay connected with their social group during the experience? It could look like making a print version of an anticipated digital game, a low-fidelity digital design, or even a fake version of something that we knew would eventually need to be replaced with the real thing.

3. Public piloting: putting prototypes into the hands of potential end-users as soon as possible

Once we had working prototypes, we would focus on testing them in the real world as soon as possible. For example, getting that print version of the game out into the galleries where visitors could interact with it. Or developing research instruments (similar to the user research process described above) to collect objective data. We had to ask ourselves: What are the questions the prototype was designed to answer? (E.g., how long will these experiences take, and what are visitors’ time thresholds?) What sort of data will be needed to provide those answers? (E.g., measurements of start and end times; user feedback on the time spent.) What evaluation instruments will be required to collect that sort of data? (E.g., a form to record time; questions for gathering user feedback)

4. Iterative design: build, evaluate, revise, repeat

Once we ran prototypes with visitors, using them to answer our initial design questions and learn whether we succeeded or failed to meet the needs of visitors, we used what we learned to repeat the process: coming up with new design questions, building new or revised prototypes to answer those questions, and taking them out in the next piloting sessions. This iterative design process saved us time and resources by preventing us from assuming at the start that we already knew what visitors wanted, or the best way to apply emerging technologies with new learning affordances, and instead develop through a design practice—often today called Lean UX—that forced us to validate our assumptions and pivot, often multiple times, until we had a successful end product.

5. Youth collaboration: co-designing with young people

One of the best ways to learn a new topic or skill is to teach it to others. Inspired by this principle, we offered after-school programs to high school youth where they learned to teach others, including online students and museum visitors, through digital media production. They co-developed games on mobile apps, augmented reality card games sold in exhibition stores, and facilitated role-playing adventures. We taught then both the science and design skills needed to combine the two into the process described above and matched them with seasoned experts who could supplement their beginner-level skills to ensure the project had the required resources.

6. Teaming up: collaborating with peers and external partners

Those seasoned experts came from both within and without the museum. For us that meant drawing from internal resources at the museum, like our exhibitions, staff scientist, and communications colleagues, as well as external contacts like paid vendors, partners, and community stakeholders.

At the end of 2020, Sebastian Chan, the Chief Experience Officer at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image, reflected on his blog that:

Reading…oral histories [of old video game designers] reminded me of how little the museum sector tells, or records, its own stories. And how, with the pandemic, this has heightened the stakes. Museum technology used to be optional. For a medium or large sized museum it no longer is. It is essential as plumbing.

Seb inspired me to tell my story about digital design in museums—both the highs and lows—so we can learn from the past as we design the future.

As you engage in your own work, I hope you will draw from stories like mine as you learn to tell your own.