This article originally appeared in Museum magazine’s July/August 2023 issue, a benefit of AAM membership.

To reach rural schools, staff at the William King Museum of Art get in the Van and Gogh.

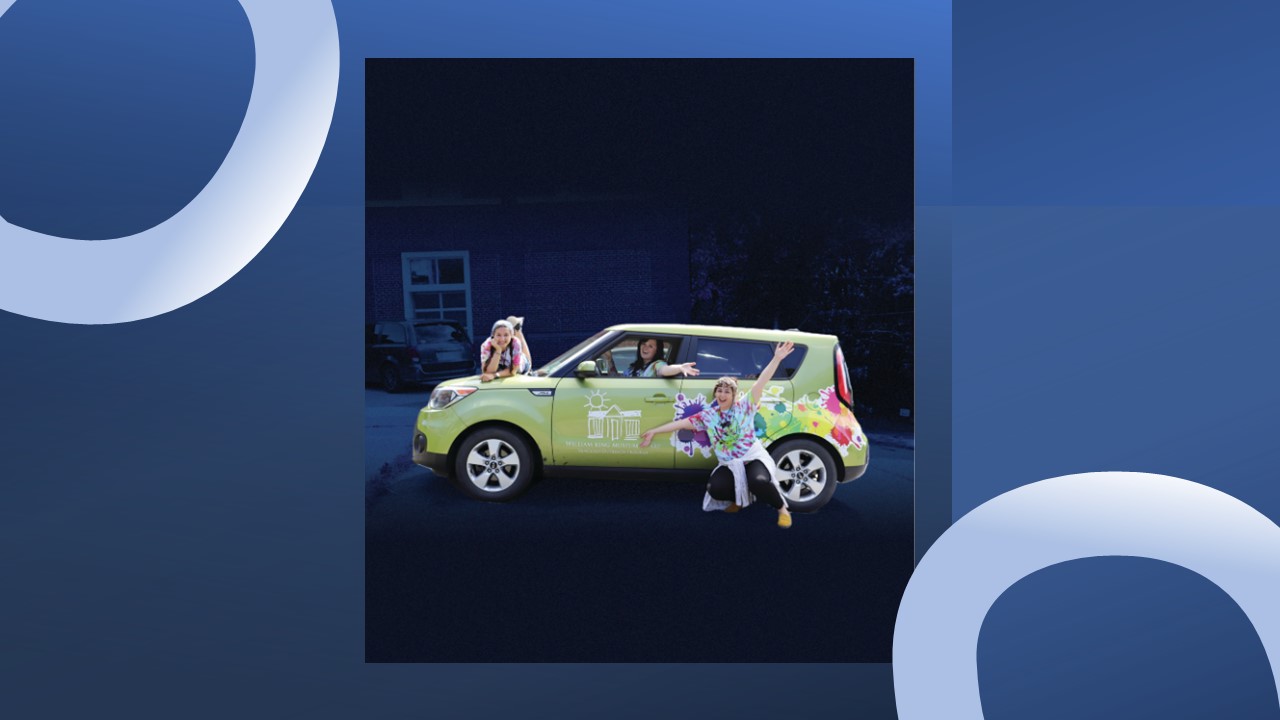

For elementary school children in Southwest Virginia, Vincent Van Gogh’s name evokes not only the expected vision of swirling colors in a starry sky, but also an eagerly anticipated visit from one of the William King Museum of Art’s (WKMA) decorated vans. WKMA’s VanGogh Outreach does not have anything to do with the post-impressionist. The name refers to the fact that we use our “vans” to “go” out into local second- and third-grade classrooms with totes filled with art supplies and captivating props for an art enrichment experience.

VanGogh Outreach covers 11 counties in rural Southwest Virginia, reaching 44 elementary schools, about 200 classrooms, and about 4,200 schoolchildren over the course of a school year. All 11 counties participate in the third-grade program, and four counties participate in the second-grade program, as well. We visit every participating classroom three times a school year for a 90-minute program. Four instructors drive the museum’s four VanGogh vans up to two hours away to reach the rural school systems that make up our service area.

VanGogh Outreach is WKMA’s largest education program. It began in 1999, when WKMA leaders realized schools were having a difficult time making it to the then–art center for field trips. Rural schools an hour or more away struggled to allocate the time and funding to transport children to the museum. The art center partnered with local schools, officials, and the Virginia Board of Education to develop a solution that would fit the needs of regional schools.

WKMA is, from its founding, an institution that not only preserves and displays the cultural arts and crafts heritage of southern Appalachia, but is also quite literally shaped by its surroundings and acts in response to community needs.

The Local Context

WKMA, a small art museum in Abingdon, Virginia, supported by 15 full-time staff and a yearly operating budget of approximately $1 million, is the only AAM-accredited museum in Virginia west of Roanoke. Nestled in the scenic Blue Ridge Mountains and close to Tennessee, West Virginia, Kentucky, and North Carolina, WKMA is proudly Appalachian (importantly, pronounced app-uh-latch-an).

WKMA was founded as the William King Regional Arts Center in 1992 as part of a project to renovate and repurpose the 1913 building that was formerly William King High School. WKMA’s Betsy K. White Cultural Heritage Project began in 1994 as a survey of regional arts and crafts. This project now fills our permanent collection gallery and has led to over 40 original exhibitions and two books. The museum’s three rotating galleries are dedicated to historic regional artifacts, contemporary regional art, and global historical or contemporary art. Fulfilling the tagline “never the same museum,” we maintain a schedule of eight to 10 changing exhibitions every year. WKMA is open seven days a week and always free to visit.

Abingdon is a small town of about 8,000 people, and the 21 counties that make up the entire region of Southwest Virginia contain roughly half of the population of Richmond, the state’s capital. Furthermore, much of the region has limited financial resources. For example, from 2017 to 2021 Dickenson County reported a median household income of $33,905, compared to the state average of $80,615. Lee County reported a poverty rate of 25.1 percent. Both counties participate in the VanGogh outreach program. Roughly half of the schools we visit have no art teacher.

Southern Appalachia is a historically disadvantaged region, but it is also home to a deep-rooted folk arts and crafts tradition. Abingdon was founded as a town along the Great Wagon Road that led settlers west from Philadelphia. Craftsmen arrived early in the town’s history to sell furniture, ceramics, rifles, and more to those seeking new homesteads in the mountains. Washington County, home to Abingdon and WKMA, was the largest producer of ceramics in the country in the years following the Civil War. Craft was also a necessity of living in a region isolated from the development occurring in eastern cities. Spinning, weaving, quilting, and basketry were commonly practiced throughout the 19th and even 20th centuries when industrialization had eliminated the need for household textile craft in other parts of the country.

WKMA reaches a geographically wide service area to offer cultural heritage preservation and art education to a rural population that could not otherwise access an AAM-accredited art museum.

Using Art to Enhance Learning

A VanGogh Outreach classroom visit lasts 90 minutes and includes a 30-minute history lecture and a 60-minute art project based on that history lesson. These lessons are an introduction to, or reinforcement of, the Virginia social studies Standards of Learning. The history lecture always includes 3-D visual props, often replicas of artifacts or artworks, keeping with the museum’s object-based learning standard. The three third-grade VanGogh visits cover ancient Greece and Rome, ancient China, and ancient Mali. Second-graders in Virginia learn about Native Americans, and our three visits review the Eastern Woodlands, Plains, and Southwest regional cultures.

In the fall of 2022, we began connecting social studies topics to math, science, and reading. For example, for ancient Greece and Rome, students created and decorated a cardstock tetrahedron, also known as a four-sided triangular pyramid. Transforming several 2-D equilateral triangles into a 3-D shape helps students actualize the abstract polygons that they learn about in third grade. We also discuss how the ancient Greeks associated Aristotle’s elements—earth, water, air, fire, and later aether—with Plato’s five geometric 3-D shapes, and students often create element-inspired designs on the faces of their shape. This engaging, interdisciplinary lesson is relevant to existing classroom topics while also bridging subjects and broadening historical understanding.

For ancient China, we painted floral blue decorations on white plant pots to emulate Chinese pottery. We also provided wildflower seeds for these pots so that students could witness the plant cycle that they learn about in third-grade biology. Some teachers chose to use the pots and seeds as a classroom science project. In the final lesson, ancient Mali, students created drums like those used by griot storytellers. Museum instructors shared a shortened version of the tale of Sundiata, the founder of the Mali Empire, and students broke down the key plot points of the story: a third-grade language arts exercise.

For Eastern Woodlands cultures, second-graders translated a Haudenosaunee story about the mythical hero Waynaboozhoo into drawings on Model Magic beads. Museum instructors used pipe cleaners woven into plastic grids to replicate the style of Plains-culture quillwork, using symmetry as a design concept and mathematics connection.

Finally, for the Southwest region lesson, students examined images of genuine, historical artworks and symbols and created “fossils” by pressing shells into clay slabs to replicate Anasazi petroglyphs, connecting a science topic to history and art. Fossils can be found alongside Anasazi petroglyphs in Southwestern canyons and may have informed the development of Southwestern cultural belief systems. We used recent publications developed by or in collaboration with tribe members when developing these lesson plans. We wanted our lessons on Native American cultures to be in touch with contemporary research.

By reinforcing social studies lessons from Virginia Standards of Learning, we can fit this program into teachers’ busy schedules while offering children an object-based and project-based educational experience. We always ask students if they remember what we talked about the last time we were there, and the kids demonstrate strong recall of the history lessons and especially the art projects. I have even met many adults in the region who tell me about the VanGogh visit they had as kids—their favorite day of school.

VanGogh Outreach is funded by a consortium of private donors, primarily foundations formed to fund programs for the counties we visit, and the school systems. Half of the cost is fulfilled by the schools, billed after the three visits are completed, and the other half is covered by the annual foundation donations.

Improving a Needed Program

We email surveys to teachers immediately following each visit, using a mix of 1–5 “do you agree” questions so that we can gather consistent, comparable quantitative data. The surveys also include free-response questions whose answers help us reflect on the program. We also use those answers as testimony in grant applications.

Teachers often share that several barriers prevent them from being able to provide this kind of experience to students on their own. They would need to purchase all of the art supplies themselves, find time to develop the lesson plan in addition to their regular lesson plans, and then fit the extra activity into their teaching schedule. WKMA and school principals manage the scheduling for VanGogh Outreach, often rearranging recess and lunch times on the days we visit.

Art education is largely unavailable in our region, and VanGogh offers art enrichment that advocates for the effectiveness and value of art education. It has never sought to be a replacement for in-school art education, or to act as a “band-aid” for that missing element. Unfortunately, art education has not increased in our region since 1999, and sadly some seem to see this program as a sufficient art experience for elementary students.

Even though outreach such as this does not directly bring people inside the museum, it is an important part of WKMA’s mission. After a VanGogh visit, every student is given a sticker that includes the name of the program, museum, and donors. I recently received a phone call from a parent after her child came home from school and told her what they did in class that day. She had never heard of WKMA and was excited to bring her children to the museum.

How to Develop a School Outreach Program

Reflect: examine how your museum’s mission relates to the needs of the community.

- Does the mission mention object-based education? Is that missing in local schools?

- Is your museum seeking to address a disparity in the community? Could outreach help bridge a gap in educational opportunities?

- Are there schools that don’t have the time or resources to send children on field trips to your museum?

Collect data: how can you Illustrate the need for an outreach program to present to potential funders?

- Is there a community in your service area that doesn’t visit the museum?

- Is that community lacking resources compared to those that more regularly visit the museum?

Seek support: are there donors, lawmakers, or school officials who will support this initiative?

Focus on quality: work with your state department of education, survey teachers, and hire full-time, experienced instructors if possible. Delivering an effective program is the best way to ensure schools and funders will want you back year after year.

Review: send out surveys you can use to build a database of comparable survey data over time.

Comments