The High Museum of Art considers polarization, values, and civic good in its art education programs.

This article originally appeared in Museum magazine’s July/August 2023 issue, a benefit of AAM membership.

Our nation’s increasingly polarized political climate requires museum educators to navigate sensitive topics and conflicting opinions, subjects that previously were often kept private in the name of gracious welcome. At the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, Georgia, an art museum with an educational mission, we take this responsibility seriously. We prioritize our work as a knowledge-building institution by developing new lines of inquiry and sharing ideas through our collections, exhibitions, and programs, thereby engaging broader conversations that shape today’s world.

To do this, we have implemented two key educational interventions: first, a high-level strategy for engaging school districts with restrictive curricular mandates and, second, an on-the-ground set of principles (and revised language) for museum educators discussing charged topics with diverse audiences.

School Districts and Museum Curricula

Each year, we develop contracts with local school districts that articulate our commitments to one another. Last fall one of our districts provided a draft contract with a new addition:

“Neutral: All services provided by Organization under this Agreement will be secular, neutral, and non-ideological in content.”

This addition reflects our current political context. Across the US, educational curricula within and beyond schools are being reviewed with greater rigor due to concerns from local officials, parents, and other stakeholders regarding what children learn.

This particular phrasing, however, was a problem for us as an art museum. The prohibition of “non-neutral” content, at face value, encompasses most of the art in our collection. As written, the addition seems to forbid students from seeing any work that contains religious imagery or icons (much of our European and African collections), work that conveys or engages with any ideology (much of our modern and contemporary art), or work that conveys a perspective other than “neutrality” (arguably all of our collection, as each work is made from a specific perspective). Functionally, keeping this contract addition would make school visits nearly impossible.

Faced with this dilemma, I discussed with our school and teacher team how best to respond. We quickly deduced that the district’s intended goal was not, in fact, to limit student exposure to art; rather, the goal was to mitigate cultivation of dogma, of religious and/or ideological bias in curriculum.

The museum is a site of knowledge production, and we recognize that good ideas are rarely created in a vacuum. To build high-quality learning experiences, we cannot limit our teaching to a single way to proceed, but instead must consider a broad spectrum of ideas. Doing so allows learners to critically engage with the greater body of experiences, identities, affinities, and beliefs that shape our contexts.

Working alongside the museum’s general counsel, we ultimately offered the district a counter-proposal:

“Non-Dogmatic: All services provided by Organization under this agreement will be non-dogmatic in content.”

The district agreed to our revised language. Rather than interpreting the district’s proposed language as an attack on experiences, identities, affinities, or beliefs, we clarified what museum education can be at its best: non-dogmatic, able to approach and consider radically different perspectives in a productive learning environment.

Gallery Learning as Ethical Practice

Museums are a place where art gets to be public, and publicly presented art speaks to all who enter a space. Museum professionals must therefore ask an ethical question: How should we interpret the ways art intersects with people’s contexts?

Museum educators have, over time, held different interpretive principles. Some of the earliest museum educators were collectors: people who amassed art and curiosities and were often eager to transfer their perspective and values to others. With the rise of public museums, more people began to see art collections, and visitors interpreted art using their own values.

As the field professionalized, museum educators began to understand that they were not only conveyors of expert knowledge to a broad public but also listeners developing community engagement. Museum educators, then, began to convey the needs and desires expressed by members of the public to museum leaders, creating a more dialogic framework for art interpretation.

As we consider how our museum’s collections and exhibitions connect with our visitors, four words serve as a bridge: experiences, identities, affinities, and beliefs. Their abridged versions follow:

Affinity: an attraction or feeling of kinship

Belief: a value or set of values

Experience: something that happened and is remembered

Identity: characteristics that establish a sense of self

We invite people who want to emphasize cultural similarities and those who want to emphasize cultural differences to see the value of one another’s perspectives along these four trajectories. Importantly, these words also negotiate ideas that otherwise can be held as antagonistic poles of political belief. We do not frame our work as emphasizing equity and diversity on one side, or shared national identity and religious sentiment on the other side. Instead, we seek to create a public space that welcomes all Atlantans, one where anyone can ask questions, learn, and grow.

This is not an easy mission—it is much easier to bond across shared values than it is to generously consider a position different from one’s own—but we see this as critical work for knowledge building and our responsibility as a civic institution.

Values-Engaged Gallery Teaching

To introduce this perspective to our newest docent class, we recently hosted a session called “Understanding Our Values.” This session frames the work of teaching and learning as a generative ethical space. First, we acknowledge that artworks express values. Sometimes, an artwork expresses values that correspond well with our own, and sometimes an artwork expresses values that raise questions or differ dramatically from our own. Uniquely, the museum is a civic space where we can productively investigate these similarities and differences.

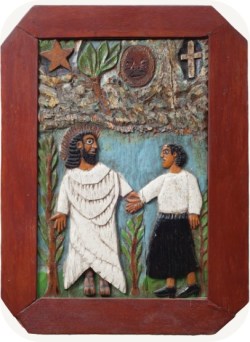

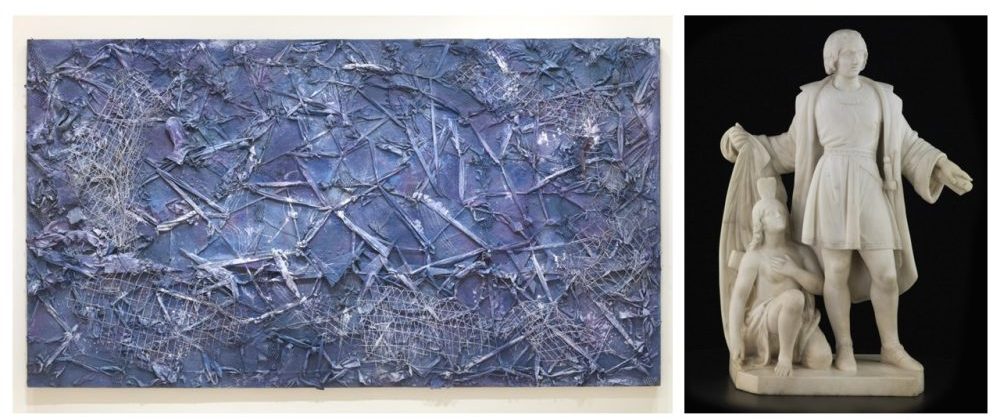

We began the session with works of art. After visually exploring the works, we posed provocative questions. With Elijah Pierce’s Christ and Lady (below, left), we asked, “What does it mean to consider a work of art that, for example, was made by a person whose father was enslaved and includes Christian iconography?” With Thornton Dial’s Crossing Waters (below, middle), we considered, “What does it mean to value an artwork made from materials collected from a rubbish heap and then hidden in a barn?” Then, with Edmonia Lewis’s Columbus (below, right), we asked, “How do we witness a figurative sculpture that conveys multiple histories?”

Atlanta is a unique city, and our museum draws people with vastly different lived experiences. Everyone, regardless of age, gender, race, religion, income, politics, social class, or disability, can and should be able to engage with artworks in our galleries. Each teacher and learner brings a specific set of experiences to the table, and museum educators must notice and appreciate these social values.

However, before we can engage with others, we must first ask ourselves: What experiences, beliefs, identities, and affinities inform my sense of self and how I see the world? Further, how do I describe my own social values, and how do I describe those of others? In our session, we explored the definitions of our four key words to frame social values and how we individually hold these ethical considerations.

Then we moved the focus to the people who join us for gallery learning experiences. Rather than assume that all people in a group are equal, or that all groups are the same, we strive to see people with the same degree of observational nuance that we offer works of art. What experiences or beliefs motivate a person, and how does that show up in their speech and behavior? What identities or affinities do they express? Are they seeking these same identities and affinities here? These questions should inform how we act, react, and facilitate tours, with a constant goal of welcoming every person and group.

Importantly, this is a constant learning process; we can never fully know a person’s experiences, identities, affinities, or beliefs, and it is often even harder to detect such values when engaging strangers. As educators, however, it is imperative that we attend to such realities, as the ways visitors conceive and build their values deeply impact how they engage with art and one another at the museum.

Art includes values that may resonate with some visitors and raise questions from others. We ask gallery teachers at the High to be prepared and willing to “go there” with visitors, engaging each artwork and visitor with sensitivity and nuance. We seek to honor and respect each person, even (and, perhaps, especially!) when they express values that differ from our own. During our tours, we must listen deeply and notice when our words resonate and when we need to monitor and adjust, or moderate, to build deeper understanding.

When we invite visitors to engage with multiple perspectives and histories in art, we create opportunities to better understand ourselves, one another, and the wider world. Both our interventions—engaging school districts with restrictive curricular mandates and adapting these principles for museum educators discussing charged topics—offer replicable strategies for cultural institutions facing similar challenges.

Tips for Values-Engaged Teaching and Learning

Accept that self-knowledge is critical for any engagement with values. What experiences, beliefs, identities, and affinities inform your sense of self and how you see the world? How do you describe your own social values, and how do you describe those of others?

Consider how a particular artwork represents or questions values. What values are foregrounded, and who holds those values? What values are not foregrounded, and who holds those values? How does that influence our understanding of the artwork? Does our understanding of an artwork shift if we consider the values of the artwork’s maker, commissioner, and/or caretaker?

Understand that many words about values are charged—positively or negatively—in specific communities. What words will you use to describe specific experiences, beliefs, identities, or affinities so that each visitor in your group feels welcomed and affirmed?

As you welcome your group, intentionally notice what values they bring with them. What experiences, beliefs, identities, and affinities motivate them, and how might these be meaningfully engaged in the tour?

Respond to disagreement with questions. Instead of ignoring someone who expresses distaste or disagreement, or quickly moving on, ask, “What makes you say that?” Asking, “What is your criteria for art?” can start productive conversations about the values people bring to a museum.

Don’t be afraid to “reset” a tour! If a conversation gets overly charged or heated, invite visitors to spend some time observing a work of art in silence, reflect in smaller groups, or consider a different artwork before returning with a new line of inquiry to the art or idea in question.

Affirm what people offer. Express gratitude when people offer insights into values that shape their engagement with art. As relevant, add context to your affirmation and explicitly call out which of the four values the person references, so the full group can better understand the contribution.

Thanks for this provocative & illuminating essay! Given objects just don’t magicaIly appear in a museum’s collection, I’d add that it would be interesting, too, for visitors to contemplate what the motives & contexts were for the curator who made the acquisition of a specific work. What decision-making values might the curator have? Was the object acquired to broaden the diversity (cultural, sexual, etc.)of artists represented in the collection? Does the work offer a compelling story in & of itself even if nothing were known of the artist/creator? Could the reason it was acquired have changed over time? Who at the High brings forth potential acquisitions to the consideration process & who (board, educators, curatorial, conservation) has input on or approval of the object? In my career, I worked as a curator of both history & art collections at three different institutions, & envisioned my role as being, at once, a revisionist & a futurist. In the former role, I would delve into the extant collection & see what other stories the object might embody that were different from the reasons it was originally acquired. As a futurist, I dedicated myself to attempting to identify & collect objects that might answer those questions that had not yet been formed or articulated…time will tell on that one!

Excellent piece, congrats on the work you are doing! The structure you are using of Affinity, Belief, Experience, and Identity is very cogent and useful.