This year’s TrendsWatch coverage of repatriation, restitution, and reparations includes a brief mention of digital repatriation—the return of cultural heritage in the form of digital data. Today on the blog, Daniel Fonner, Associate Director for Research at Southern Methodist University’s DataArts, explores yet another variant on this practice. How can emerging digital tools help recreate cultural heritage that has been lost or destroyed?

–Elizabeth Merritt, VP Strategic Foresight and Founding Director, Center for the Future of Museums

Six years ago, I started a project called ReMasterpieces that used some of the leading AI techniques of that time to recreate works of art that were stolen and subsequently lost or destroyed by the Nazis during World War II. My original goal was to perhaps bring a small amount of closure to those who were terrorized by the Nazi regime by recreating the missing paintings and returning them. This work combined my interests in World War II, technology, and public policy related to protecting cultural heritage.

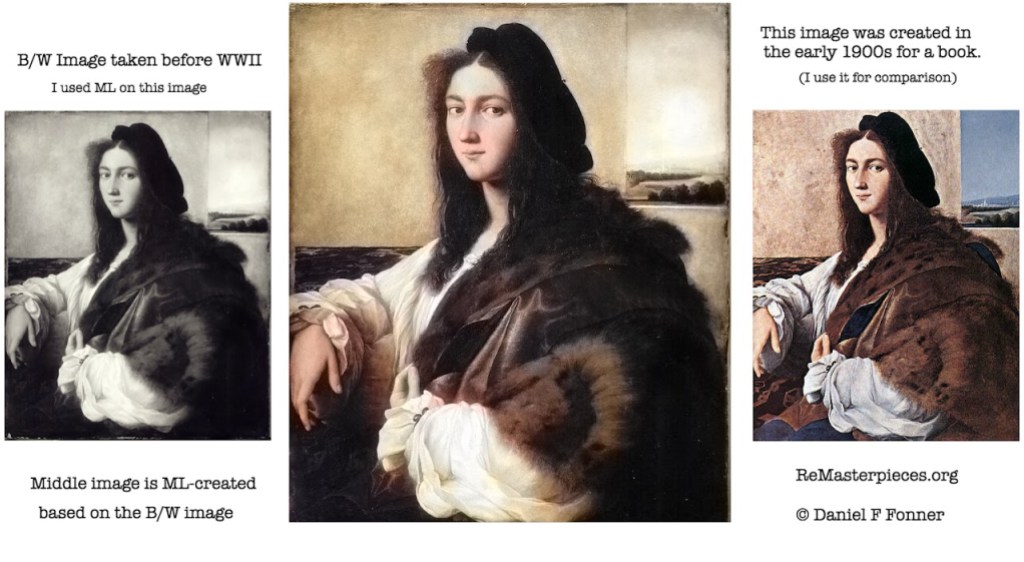

To carry out this work, I used popular AI methods of the time, such as transfer learning and generative adversarial networks (GANs), as my primary tools to recreate the missing works based on small black-and-white photos. Transfer learning computationally identifies characteristics in an image and then applies those characteristics to a new image. (For example, you could apply the style of Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night to your vacation photographs.) GANs use data to generate new images, comparing them to image databases to determine how believable they are.

Skip over related stories to continue reading articleYou can see some examples of paintings I recreated below. (I previously wrote about ReMasterpieces for the Arts Management and Technology Lab [AMTLab] at Carnegie Mellon University focusing on the intersection of this type of work with upholding the Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art.)

However, my ability to recreate works of art was limited by a lack of data to train the AI models. I needed more data on specific artists to ensure the recreations were as accurate as I could possibly make them.

So ReMasterpieces went dormant.

Fast-forward to 2022, and two major changes have prompted me to revisit this type of work: technology innovations and broader access to museum collection data.

Technological advances in general, and the explosion of generative AI tools in particular, have jump-started projects that support provenance research and lost art identification. In April 2023, the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) Art Crime Program released an app that provides a searchable catalog of missing cultural items, from Monet paintings to Stradivarius violins. Anyone with a smartphone or laptop can scour the database to help the FBI locate missing objects. Interpol’s ID-Art mobile app is even more powerful, because its AI functionality lets users compare their own photos of an object to the images in the Interpol database, similar to a Google reverse image search.

These tools have also encouraged me to restart ReMasterpieces to create more accurate recreations of lost art. Part of the difficulty of producing recreations is that many images of lost items are black-and-white photographs with unique patinas based on the age and specifications of the cameras used to take the photographs. Computationally comparing these photographs with high-resolution images from our modern smartphones can lead to many false negatives in the search for missing works.

Broader access to museum collection data has enabled the development of better tools to recreate missing works of art and find links among various cultural items and the journeys they have taken. This is where museums themselves have a unique opportunity to lead in provenance and discovery efforts. For example, models such as Yale University’s LUX platform and the Carnegie Museum of Arts’ Art Tracks initiative show how leveraging big data frameworks can enhance collection transparency and provide rich data to power tools like ReMasterpieces or future developments of the FBI’s missing art app.

It is important to note, however, that the positive ethical framing of recreating and documenting our collections with AI is bound within the very real societal and climate impacts of AI technologies. From CO2 emissions and water consumption at large data centers around the world to unregulated labor and intellectual property issues, we must balance what we can do with AI with what we should do. This is a difficult balance as tools become easier and easier to use across various domains. Is there a perfect answer to these issues? No, but that does not absolve us from critically evaluating any work we do in this domain.

As we continue down this path of continued integration of AI into our personal and professional lives in the museum sector, it is critical that we evaluate and potentially integrate new technologies into our work. This can enhance the value of our collections and contribute to a broader conversation about documenting provenance helping to identify missing cultural items that could be hanging in our galleries or homes. AI is far from the answer to everything; expert knowledge and human connections will always be critical in learning about the past, the future, and our humanity—but responsible AI use might be able assist us on that journey. Museums can be at the forefront of this important work, collaborating to best organize collection data digitally and contribute to technological efforts to find or recreate missing items of our cultural heritage.

Comments