Twenty-two years ago, I was leading the strategic planning process for a museum education department when I noticed something interesting. Even though we called ourselves the “education” department, we had worded nearly all of our intended outcomes as “learning” instead. The distinction might seem minor at first glance, but the more we talked through our goals, the more significant it became. Educating people, as American art museums had long prioritized, implies a one-way transmission of knowledge, whereas learning centers and empowers the stakeholder to actively co-create their own experience. Our own language was telling us something: our center of gravity needed to shift. In the end, we renamed ourselves the Department of Museum Learning and Public Programs, and I carried that perspective with me as I moved into leading academic art museums.

Asset-Based Community Development & the Ladder of Citizen Participation

While our field’s understanding of the need to share authority with our stakeholders has continued to evolve over the last two decades, it was not until 2017 that I came across a framework which clearly delineated how to do this. That year, the Haggerty Museum of Art, located at Marquette University in Milwaukee, joined twelve institutions to participate in the first round of the Institute of Museum and Library Services’ (IMLS) Community Catalyst grant program. The program explored how museum practice changed with a paradigm shift from the museum as community anchor—a centralized site for community gathering and dialogue—to a catalyst directing its energies outward to the community, which serves as the anchor itself.

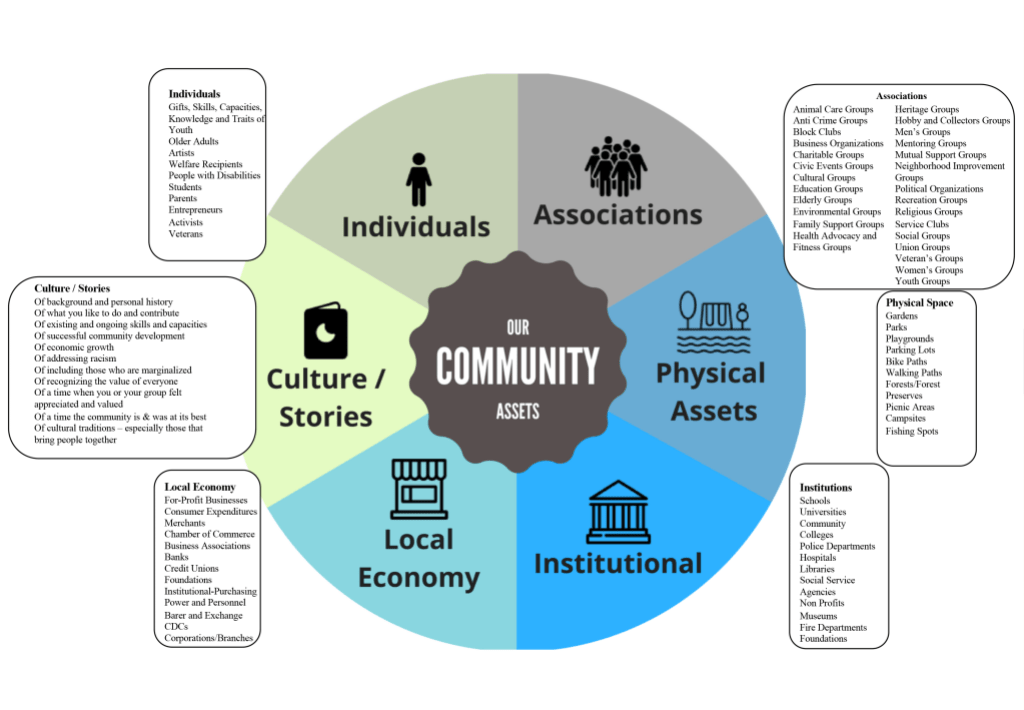

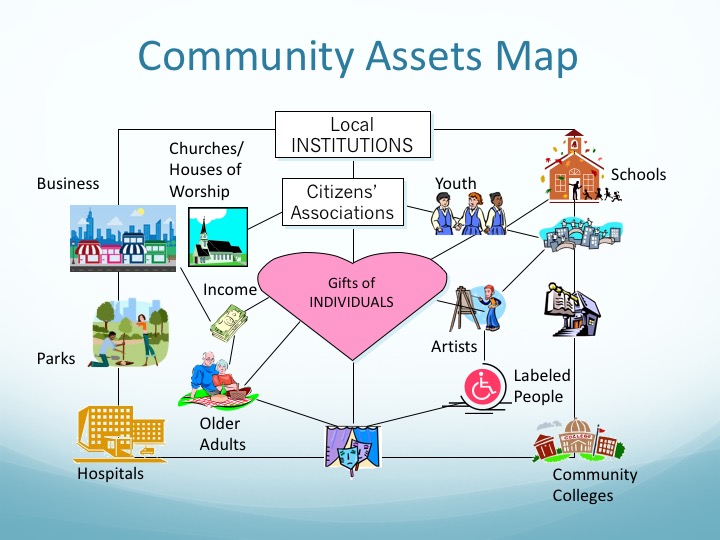

To drive this paradigm shift, IMLS worked with the ABCD Institute at DePaul University to train all grantees in the practice of Asset-Based Community Development (ABCD). That training provided an eye-opening way to look at the limitations of historical museum practice. For too many years, museums have approached our communities with a deficit mindset. We’ve looked for some of the worst problems in our community—housing issues, low graduation rates, unemployment—and decided that, through outreach to the less fortunate, we would solve them. In working with partners on collaborative funding proposals, we’ve essentially required them to denigrate their own communities to garner support. This approach, rather than yielding solutions, has resulted in damaged partnerships and disempowered communities. The ABCD framework, on the other hand, approaches communities from an abundance mindset, with a consideration of their many assets: individuals, associations, institutions, physical space, exchange, and culture/stories/history. Under this framework, museums can use their own assets to catalyze those community assets, resulting in community development and empowerment.

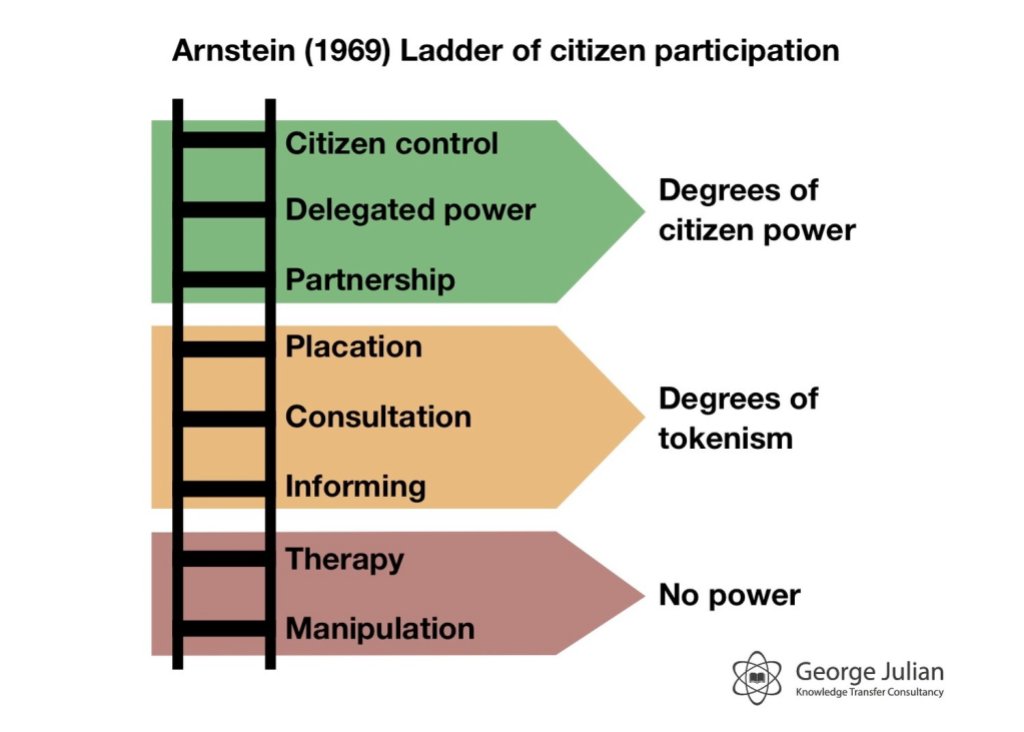

The other paradigm-shifting framework we learned through the program was Sherry Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation. On Arnstein’s metaphorical ladder, stakeholders move up from “nonparticipation” (no power) to “degrees of tokenism” (counterfeit power) to “degrees of citizen power” (actual power). This model also had much to tell us about how to genuinely empower our communities. The lowest rung, nonparticipation, equates to the historical deficit-based approach of museums, which Arnstein characterizes as “manipulation” and “therapy.” While one hopes that few museums work this way anymore, many of us certainly engage our communities on the middle of the ladder—degrees of tokenism—which she defines as “informing,” “consultation,” and “placation.” Take, for example, advisory councils. Even if museums listen to and respect the advice such groups give, the institution ultimately chooses which feedback to incorporate—and which not to incorporate—into its activities. The model showed us that truly sharing power would mean moving to the top of the ladder, degrees of citizen power, by engaging in truly bidirectional partnerships, delegating power to stakeholders, and centering stakeholder agency and control.

Translating Theory into Practice

Having learned this invaluable theory to inform our work, the Haggerty moved into the activity phase of our Community Catalyst grant: a socially engaged public art project in which local artists and members of Milwaukee’s southside community collectively explored how water affects our lives.

Using the principles of ABCD, we began by defining the community assets the initiative would catalyze, prompting us to identify partners far beyond those typical for art museums. These included Milwaukee’s Sixteenth Street Community Health Centers (SSCHC), the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District (MMSD), local conservation group Kinnickinnic River Neighbors in Action (KKRNIA); Milwaukee County’s public Pulaski Park, the community of Milwaukee-based artists and scientists, the Water Quality Center at Marquette University’s College of Engineering, Marquette Law School’s Water Law and Policy Initiative, the gifts and talents of people living in Milwaukee’s southside neighborhood, the Kinnickinnic River, and MMSD’s “re-greening” of that river. This ten-year flood management project removed more than seventeen hundred feet of cracked and broken concrete river lining and restored the Kinnickinnic River to a natural stream in Pulaski Park. It also required that twenty-seven houses adjacent to the river be demolished, leaving an open space that neighborhood residents were committed to transforming into a welcoming community space.

To animate that newly open space, the Haggerty selected three socially engaged local artists, who were paired with scientists selected by MMSD to lead community walks during which neighborhood residents, artists, and scientists discussed the role of water in their individual and collective lives. Informed by those dialogues, each artist submitted a proposal for a public art installation for the site, which they shared during KKRNIA’s annual picnic, where community members voted for their favorite. The winning design was Gabriela Riveros’ Here Live Our River Gods/Nuestros Dioses Viven en Eli Rio, a series of panels illustrating water deities from cultures historically represented in the neighborhood.

As part of our evaluation of the initiative, we used a participant engagement scale derived from artist and educator Pablo Helguera’s book Education for Socially Engaged Art: A Materials and Techniques Handbook. That scale assessed the nature of participant involvement inherent in each program component as either “nominal,” “directed,” “creative,” or “collaborative.” This analysis revealed that the Haggerty’s evolving understanding—and adoption—of ABCD principles yielded unanticipated changes throughout the program period that gradually moved residents and partners up the Ladder of Citizen Participation. Those stakeholders were, as it turned out, lower on the ladder at the beginning of the project than we had realized. Humility and flexibility on the museum’s part were both key. For example, the Haggerty had initially decided that only one public art project would be developed. However, voting at the KKRNIA picnic was so close that community members—entirely independently of the museum—decided to also realize artist Mollie Oblinger’s Bird and Bat Houses. The Haggerty’s only role in that project phase was to write a letter of support to the Milwaukee Arts Board, which supported Oblinger’s installation. We also heard anecdotal feedback that spoke to how meaningful the project had been for participants. For example, one SSCHC colleague told us the impact had been seeing that “the Haggerty is not just a place you go.” I knew exactly what they meant. The museum’s intangible mission and impact had clearly transcended its building. When asked about the desire to continue this partnership, the same collaborator replied, “Oh, we’re married now!” Something important had clearly shifted in the museum’s work.

[For more on the project, see the Haggerty Museum of Art’s blog and Journey Map.]

A Permanently Changed Paradigm

While our experience shows how powerful ABCD can be for museum practice, it requires a relinquishing of control that does not come easily to many museums. At the beginning of this project, a wise consultant advised that the Haggerty think about ABCD as a machine. “The machine,” they said, “knows what it wants.” And it does. Catalyzing one community asset always leads to the catalysis of another. ABCD’s self-propelled machine can take museums places that they never imagined, resulting in much deeper and longer-lasting impact than they could have envisioned.

That has certainly been the case at the Haggerty, where it has had a profound, long-lasting impact after the end of the grant program. Museum staff now joke that they’re permanently wearing “ABCD lens,” and can’t imagine engaging with either the Marquette University or Milwaukee communities any other way. When the Marquette University Student Government proposed that a local artist be commissioned to create a mural celebrating Marquette’s Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) community, for instance, the Haggerty implemented a campus-wide ABCD approach. The resulting mural, Mauricio Ramirez’s Our Roots Say That We’re Sisters, enjoys so much shared ownership that it inspired an ongoing podcast series shining a light on accomplished BIPOC women in the Marquette community. While the Haggerty had some involvement with the podcast launch, the series is now fully managed by Marquette’s Office of Diversity and Inclusion. The machine knew what it wanted.

Centering our communities in this way has also significantly changed the way that the Haggerty approaches exhibition development. Several years ago, I asked a colleague at another academic museum how they aligned their parent (private) university’s mission with their exhibitions. “We don’t,” they replied, “We focus on the quality of the art.” They, of course, are not alone—many museums have historically viewed their role as transmitting expertise to a presumably receptive audience. Enter, again, the distinction between education and learning. ABCD, though, means that the museum is catalyzing community assets using the museum’s many assets—including exhibitions, collections, knowledge, connoisseurship, and engagement with artists.

A perfect example is the Haggerty’s spring 2023 exhibition Tomás Saraceno: Entangled Air. When Marquette’s (now) Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering Dr. Somesh Roy participated in a new faculty orientation session at the museum, he asked if the Haggerty would be interested in integrating his research about soot into an exhibition. Without knowing where the ABCD machine would take them, museum colleagues said “Yes!” Dr. Roy subsequently received a National Science Foundation CAREERS grant to create a framework that will model soot emission from combustion engines, leading to cleaner combustion systems. Engagement with the Haggerty was written into the grant, and the museum organized an exhibition of work by Argentina-born, Berlin-based artist Tomás Saraceno. For more than two decades, the internationally acclaimed Saraceno has activated projects aimed towards rethinking the co-creation of the atmosphere with the goal of eliminating carbon emissions. Public programs aligning with the Haggerty’s exhibition included AirWalks—presented in collaboration with community partners including the Urban Ecology Center and Sixteenth Street Community Health Centers—that explored the interrelationship between industrialization, air quality, and public health. Air quality data collected during AirWalks were converted into visualizations that were displayed in the interpretive space accompanying the Saraceno exhibition. This initiative deeply engaged both the Marquette University and Milwaukee communities, and a conversation conducted via Zoom between Dr. Somesh Roy and Tomás Saraceno reached participants from across the United States and several countries.

Centering and catalyzing community assets has permanently liberated the Haggerty Museum of Art from the siloed hierarchies—including those between museum learning and curatorial areas—that too often constrain museums’ work. The ABCD machine has no interest in, or use for, any such thing. Those constructs, along with the many structural inequities carefully built into the traditional museum paradigm, collapse when a museum shifts its center of its gravity to community assets.

Perhaps the most significant impact of ABCD has been on the Haggerty’s mission and vision statements. Approaches that felt right to us just a few years earlier lived uncomfortably low on the Ladder of Citizen Participation. So, we changed them. The museum’s new mission statement is, “The Haggerty Museum of Art connects people—on campus, in the community, and around the world—to art, to ideas, and to one another. Through inclusive programming, the museum uses the interdisciplinary lens of art to cultivate knowledge, insight, understanding, and belonging, all in service of Marquette University’s commitment to care for the whole person.” And its new vision statement is, “The Haggerty Museum of Art sparks transformational experiences with art that amplify personal, intellectual, social, and physical well-being.”

This work is never completed, and we’ll never get it entirely right. However, Asset-Based Community Development and the Ladder of Citizen Participation have provided critically important, actionable frameworks—ones which I believe can be implemented by any museum.

Comments