When we think about barriers to change, practical issues like time, money, and legal issues often are top of mind. This can be true, for example, when museums talk about repatriation, whether voluntary or mandated by law. But often the most daunting roadblocks lie within ourselves—our assumptions and habits of thoughts about how things should or must be done. Today on the blog, Oberlin student leader Isabel Handa and professor Amy Margaris talk about how they came to co-courier the return the skull of an ancestor to Hawaii, how this process illuminated the differences between museum and Native Hawaiian perspectives on roles and protocols, and the need for museums to learn trust, respect, and open-mindedness towards Native people.

—Elizabeth Merritt, VP of Strategic Foresight and Founding Director, Center for the Future of Museums

Introduction

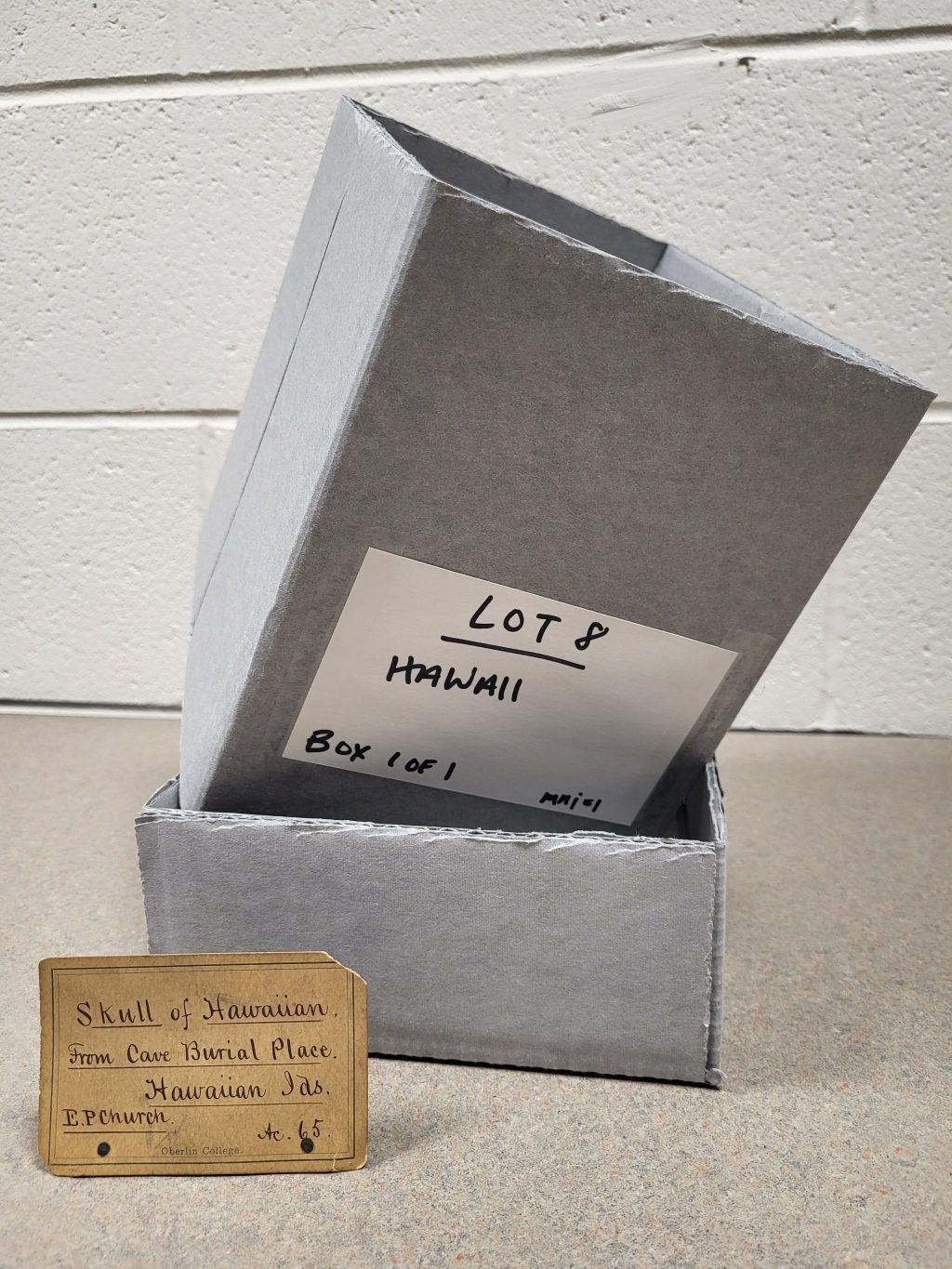

It’s May 2023, and a nineteen-year-old Oberlin College student and a professor she’d met just two weeks before are aboard a plane to Hawaiʻi. In the student’s backpack, wrapped in pounded kapa (bark cloth), is the skull of a Native Hawaiian kupuna (ancestor) who is returning home after a century and a half.

This essay, written as a dialogue between that student and professor, moves beyond the legal aspects of repatriation to explore the restorative actions that surrounded the kupuna’s return. In it, we discuss inherited trauma linked to historical teaching collections, welcoming both Indigenous and Western forms of knowledge in the academy, and our advice to other Indigenous individuals and collections stewards for successful collaboration.

Some background

Isabel K. Handa: I did not grow up knowing very much about my Hawaiian heritage. It was not until sophomore year of high school, when the leading force in Native Hawaiian repatriation agreed to teach me about our heritage over the phone, that I began to learn more. I did not know the scale of his work at the time, but Halealoha Ayau would always answer my questions over emails and phone calls. Later on, when I went to Oʻahu for a gap year before starting college, he began inviting me to his events. I thought that I was just observing Hawaiian practitioners at work, but I was actually being trained alongside them in the practice of repatriation and reburial. It was not even one year later that I was put in the path of the iwi kupuna at Oberlin College.

About a week before my freshman year finals, I attended my first meeting of the Working Group on Indigenous Matters with Professor Margaris. I had heard talk about Professor Margaris’ work with repatriation for a while, so I knew I had to approach her after the meeting and ask if she’d ever worked with Hawaiian bones. The way I ended up here is proof that if an iwi kupuna (ancestral bone) is ready to come home, they[1] will put you on the path to take them there.

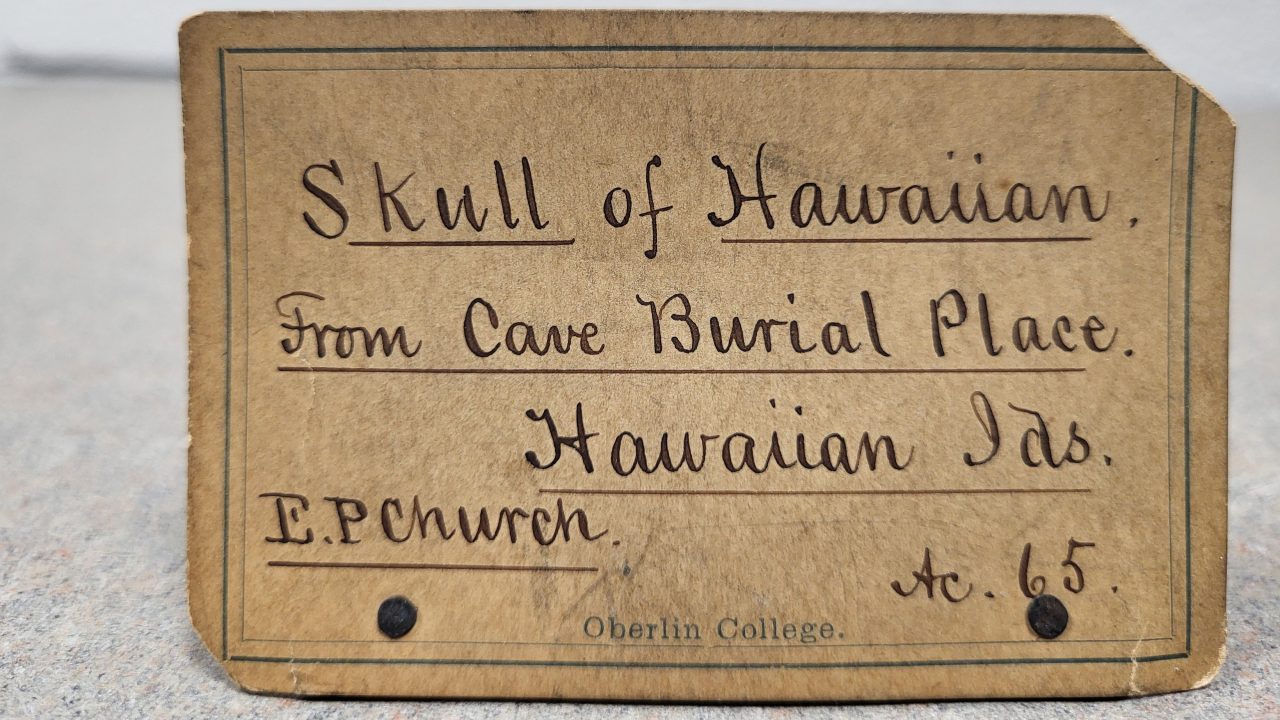

Amy V. Margaris: The working group is developing an Indigenous land acknowledgement for the college. Knowing that I was the campus Native American Graves and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) coordinator, you asked me afterwards—polite but firm—if Oberlin had any ancestral remains from Hawaiʻi. My answer was yes: a skull, sent in 1875 to augment the college’s natural history collection by an Oberlin graduate who had spent ten years as a schoolteacher on Oʻahu. I wondered what your reaction would be.

Initial reactions

IKH: I contacted Halealoha in a panic, thinking that he would send someone out and get it all sorted. But instead, he said to me, “Are there other Kānaka (Hawaiian people) [at the college]?” When I told him that there were not, he casually shrugged and said, “Well then, you’re it.” I think my heart dropped. I was going to be performing a wrapping ceremony and transporting the iwi kupuna from Oberlin back to Oʻahu.

In grief and desperation, the first thing that I did after I spoke to Professor Margaris was go to a field to pray and chant. I was asking the ancestors for help with the iwi kupuna, but honestly, I was begging for them to come save me too. I had spent the entire year slowly suffocating, feeling like Oberlin was trying to squeeze me out from all sides. From encountering ignorance about spirituality, to feeling like there was not a single spot on campus where I could safely weave or do my pule (prayers), to believing I was the only Native Hawaiian person on campus, I felt that there just was no space for me. Finding out that Oberlin had entrapped the iwi of one of my kupuna for 150 years was the last straw. I just kept thinking, “No wonder I did not feel like I belonged at Oberlin, because white kids do not have to worry about their ancestors’ bones being held at their place of residence and education.” The college benefits them, the academic opportunities benefit them, and people like me are stolen from their graves to be placed in archives as specimens. How was I supposed to feel safe? So I asked the ancestors to save both of us.

AVM: Having you appear on the scene felt like a gift because I needed instruction on repatriation in the context of Native Hawaiian Organizations (NHOs), which are set up quite differently from tribal entities in the continental US. I needed that education in order to help facilitate returning the Hawaiian ancestor, which by coincidence was next on my repatriation list. Yet, like you, I was also struck by the sense of urgency with which the kupuna needed to return to Hawaiʻi. Your mentor, Halealoha Ayau, insisted it must come home immediately and I thought, after 148 years, couldn’t we have, like, another month or two to get everything in place? The pace was crazy. I was on research sabbatical and dropped everything; one of our college attorneys likewise worked like fire on the legal agreements. And I was very concerned for you. You were balancing the enormous responsibilities of studying for finals while also weaving a basket for the kupuna and conducting prayers and chants over the ancestor.

The weightiness of the repatriation process

IKH: The weightiness shut me down. I would explain it as the Hawaiian term kaumaha, meaning that I felt the responsibility and duty to do right by the kūpuna (ancestors), lahui (Hawaiian people), and ʻāina (land). Although I was about to take my finals, the only thing that inhabited my mind was the iwi kupuna. It was worse when I was not in the room with the kupuna where they were held, because everywhere else I felt like a wandering husk. In those two weeks I was always with them, a dormant courier with the single purpose of waiting to be of service.

However, what weighed on me even more was the kuleana (responsibility) of being the courier. I was not scared of my ancestor; I was scared of letting down my ancestor. Why would the ancestor have picked me to do this work? I was a nineteen-year-old college freshman with minimal training and imposter syndrome, amongst kumu (masters/teachers) and well-experienced practitioners. I was just a kid who was not even able to set healthy emotional boundaries between myself and the kupuna. We were supposed to be respectfully strict in the distinction between duty and emotional attachments, but I was mixing in my own baggage. I would do it if Halealoha and Professor Margaris wanted me to, but I thought that it was a fluke, inevitably meant to be the work of kumu and those who were “Hawaiian enough.” The iwi kupuna deserved them, not me. And honestly, that probably hindered me the most.

AVM: This repatriation had so many working parts compared to my previous experiences, not to mention a long flight at the end of which I was to face a formidable group, members of the NHO Hui Iwi Kuamoʻo, to formally represent an institution with a role in egregious wrongdoings. Nineteenth-century Oberlin saw itself as socially progressive yet operated within a larger colonial mindset that sanctioned the looting of human remains in the name of science education. While I did not feel personally responsible for Oberlin possessing the iwi kupuna, I did feel a strong connection to the story, as both an Oberlin employee and a fellow alumnus of the man who sent the skull to Oberlin. I felt the responsibility of that legacy.

At the same time, a part of me wished someone else could make this journey instead of me. The flight was scheduled for Mother’s Day, and my mother had died only a few months before. I felt the urge to be home with my family, to take the day to honor my mother’s memory. The irony, of course, is that the trip’s purpose was to bring an ancestor home after generations of forced separation from their own family. In this way my familial loss created another thread that tied me to the iwi kupuna.

Most pivotal moment(s) in the repatriation process

AVM: In addition to meeting you, of course, there were two.

Isabel, you may not know this, but a couple days after you learned about the iwi kupuna’s presence on campus I met with the director of our campus art museum and an attorney from the college’s General Council (legal) office for advice on how, logistically and legally, this repatriation should work. How could we follow your mentor’s strongly worded suggestion that you bring the kupuna back to Hawaiʻi?

Our museum director is the one with expertise in couriering collections (in her case, works of art), and we sought her input on the process of moving items between institutions. On our campus, the art handlers are museum personnel. They have advanced degrees and long resumes. There are lots of rules and a formal chain of custody that must be followed to ensure the artwork is properly supervised and handled every step of the way from source to destination. Within this framework there was no way on earth an Oberlin freshman was going to fly across the ocean with a human skull from our collection—in a backpack. The idea seemed outlandish. But then…it happened! Twelve days later you and I were on the plane together to Hawaiʻi as co-couriers.

Everyone involved wanted this repatriation to go smoothly, but for Oberlin, having a student assume a leadership role was unprecedented; it called for a different way of thinking about collections care. And that differentness underscores the divergent meanings that have been attached to the skull: a dispossessed ancestor versus a donation to a scientific collection.

The key was separating your role as an Oberlin College student from that of a formal representative of a NHO, Hui Iwi Kuamoʻo. The latter opened up an alternative pathway for transporting significant items from the college: one that still relied on notions of appropriate training, knowledge, and stewardship practices but that widened the definition to include sources of expertise that sit outside of standard Western museum policy. Your affiliation helped Oberlin leadership (the College Dean, attorney, and art museum director) to recognize your spiritual and cultural training as legitimate and appropriate for this task, which in turn set a new precedent that will help the college as we begin developing a roadmap for future cultural property cases that don’t fall under NAGPRA’s purview. That’s Oberlin’s next big step.

IKH: What is so interesting to me is that it was almost the complete opposite on the Hui Iwi Kuamoʻo side. Halealoha and I believed that I was the rightful courier, because in past cases, it was always Hui Iwi Kuamoʻo who were the caretakers. They trained me on how to care for the ancestors on the journey home. Most of the practitioner’s job, in transporting the iwi kupuna out from the institution, is making sure that the iwi kupuna know that they are safe now, and can trust that they are in good hands, being taken home by Kānaka (Native Hawaiian people). That is why I was truly shocked when I learned, through this conversation, that there was debate over who was going to be the courier. From our perspective, I was going to be taking them with Professor Margaris accompanying, and from Oberlin’s, it was Professor Margaris taking them with me accompanying. I think that this was the most clear indication in our story of how Hawaiian and Western institutional thinking varies. In the end, however, no matter what organization said what, we both had our respective roles that could not have worked without the other.

AVM: I agree, our roles were very complementary. You assumed the primary spiritual and physical burdens. You helped me to understand the healing power of an apology, which I read on behalf of Oberlin at the mihi (return ceremony). I was able to provide logistical support, like coordinating with Marie Trottier, the TSA/Homeland Security’s Tribal Affairs Liaison with whom Halealoha Ayou set us up, who is a great resource for readers engaged in repatriation processes to know about. Among other things, Marie helped ensure the kupuna wasn’t exposed to light through X-ray testing at the airport, which would have violated spiritual protocol.

And remember when the airline attendant told us just before our connecting flight that the plane’s carry-on space was full? I was more than happy to pull the attendant aside and explain why our skull-containing backpack needed to ride with us, and definitely not with the checked baggage!

IKH: For me, the most pivotal moment was the mihi at the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum. Up until that point, I had not thought that I would be able to let go of the iwi kupuna. In my grief, despite my training, I had glommed on to the iwi kupuna. At Hui Iwi Kuamoʻo, I was trained to establish healthy emotional boundaries with the iwi kupuna so that the work does not become too heavy for either kupuna or caretaker. However, that was all lost on me, as the grief of the kupuna’s forced displacement and entrapment had mixed with my resentment towards the college. I thought my pain had grown beyond dissipation. Furthermore, at the time, I had grown extremely protective over the iwi kupuna, constantly worrying over their wellbeing. It felt like us against everyone else. Instead of boundaries, it felt like we were one.

But at the mihi, seeing the kupuna sitting at the table with the kihei (Hawaiian wrap used for ceremonies) and lei (garland, wreath, or necklace given as a symbol of affection) around them, surrounded by love and back on their ʻāina (land, that which feeds), I was able to let go. Where I thought I was going to feel grief existed only love and a sense of closure, the assurance that both of us were going on to exactly where we should be. They were finally safe and would not be burdened down by my pain.

AVM: Yes, this was a turning point for me too, seeing the kupuna on the table during the mihi. It was facing the attendees, and wearing a flower lei just like the ones the Hui Iwi Kuamoʻo crew placed over our heads when you and I arrived in Honolulu. It was then that I could fully perceive the kupuna as not just old bone, but kin. Part of an ʻohana (family). A true person.

Why this process was successful in our eyes

IKH: The reason why I feel like the repatriation was a success was because Professor Margaris respected Hui Iwi Kuamoʻo’s protocol. She did not treat the iwi kupuna like Oberlin’s property, but as my ancestor. She let me be the only one to carry and handle the iwi kupuna on our whole journey, she let me perform the wrapping ceremony in private, and she even wrote an apology for the mihi. It is the little things that show that someone truly understands and respects your culture. However, she also understood the urgency of the situation at hand, that the iwi kupuna needed to be returned home as soon as possible.

AVM: I saw the urgency from all the Hawaiians involved, from members of Hui Iwi Kuamoʻo to staff at Bishop Museum, who accepted the kupuna as a loan until the formal NAGPRA repatriation could be completed. As an outsider I can’t fully feel that urgency in my heart, but I can observe the intense conviction among those who do. From you, I’ve also learned some of the beliefs behind the desire for a very swift return. I may not fully feel it, but I can honor it.

IKH: The way that I feel that Professor Margaris honored our beliefs was through transparency, open communication, and responsiveness. Documents, signatures, and information would often be delivered within a day or two. Because of everything mentioned above, we were able to return the iwi kupuna to Oʻahu in two weeks! Most importantly, though, we did it in a way that was pono (righteous) to the iwi kupuna.

Lessons for others

IKH: One of the most important things that I want to emphasize is that an institution’s choice to hold Native possessions will affect its present-day relationship with Native peoples. How are Native people going to feel welcome, especially in liberal arts spaces, if the products of the college’s missionary past are still heavily prevalent in the current institution? The iwi kupuna was taken by an Oberlin alumnus and missionary, a direct product of Oberlin’s early missionary history. Although that was nearly 150 years ago, the iwi kupuna’s presence itself establishes that Oberlin is still a live character in the middle of its missionary chapter. Until that chapter of Oberlin’s history is officially closed, the effects will continue to permeate throughout the college’s culture and classrooms, forever reminding Native people, “in case you’ve forgotten, this space is not for you.”

However, the way towards closing these chapters is not just giving it all back. In the end, the goal for institutions is to amend their relationship with Native groups, to change the missionary and colonialist mindset by learning trust, respect, and open-mindedness towards Native people.

AVM: Isabel, you’ve been a huge force in moving our campus forward in this way. I’m so grateful for your recent help facilitating a subsequent repatriation, to a different Native nation, in which we were able to use elements of what we learned from the Hawaiʻi experience to bring respect to the process. And you led the establishment of Oberlin’s new Indigenous Students’ Council. Now that you’re my Research Assistant you can get paid for some of this important work, but I learn as much from you as the other way around. How incredible that we’ve been brought together through this process. How incredible that you wound up at Oberlin, just when Oberlin really needed you.

IKH: As for me, I realized that I did not have to be worthy in order to deliver the iwi kupuna, I just had to be ready. I know that I am not the only one plagued with imposter syndrome about my worthiness as an Indigenous person. And for me personally, I don’t think that I will feel worthy for a long while. However, for Indigenous people to hear, the kahea (call) is going to come whenever, the kupuna are not waiting for you to feel self-assured. They just want to go home, so your job is to prepare yourself to answer whenever that happens.

[1] In using the pronoun “they” I refer to the ancestor with the same personhood as us living.

Best story about Oberlin today I have read in a long time. It reflects the close student – teacher relationships I experienced at Oberlin — with evidence of growth on both sides. Congratulations to both of you. As one who has spent much time visiting friends on Kauai, I am especially happy to have read of your mutual success.

This interview was excellent and inspiring on multiple levels. It hit many notes regarding repatriation– why it matters, how to approach it, possible concerns, and things I hadn’t considered, like Isabel feeling bonded with her ancestor after caring for them. Thank you for sharing this story.

I am heartened with tears having read this. The title called for my attention. I’m reminded that it has taken so many years of advocacy that could lead to this repatriation. I appreciate the urgency and action, to recognize that yes, once upon a time and still, humans, especially “others”, have been collected and placed on display. May such work continue with such respect and grace.

When I searched “https://www.google.com/search?client=safari&rls=en&q=issues+of+mysticism+in+museums&ie=UTF-8&oe=UTF-8#ip=1″, I discovered an impressive list of discussions on the topic. However much all our ‘ancestors” struggled with the impact physical reality has on our personal experiences, obviously this conflict continues in the present day. Perhaps Galileo and Copernicus dreamed of a day that humans would imagine they were not at the center of the universe, but we’re not there yet.