The net effect of loud, sensational clamor is to mute more quiet and temperate voices. —James Davison Hunter, Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define America

This article originally appeared in Museum magazine’s January/February 2024 issue, a benefit of AAM membership.

What choices do museums face in avoiding or engaging with the current conflict?

Last year TrendsWatch examined the growing partisan divide in the US and how museums might help repair our fractured democracy. However, an adjacent trend threatens the sector’s ability to fill this reparative role: museums as battlegrounds in a new wave of culture wars. Some are criticizing museums for embracing progressive values, while others regard museums as conservative vestiges of a colonial past. With alarming frequency, climate activists use museums as stages for protest or vandalism to draw attention to their cause.

Pressure is building along fault lines that segment communities, funders, policymakers, and museums’ own staff, boards, and volunteers. How can museums defuse this tension before it causes more damage? What choices do they face in avoiding or engaging in the current conflict, and how will these choices shape the future of museums and society?

The Challenge

Disagreements about the values that should guide public and private life in America are as old as the republic itself, and these debates periodically erupt into physical violence ranging from insurrection to all-out war. The verbal conflict took center stage at the 1992 Republican National Convention when Patrick Buchanan told the audience that “a cultural war” was taking place, characterizing it as a “struggle for the soul of America.” The issues Buchanan named (abortion, homosexuality, school choice, and “radical” feminism) continue to be points of contention, but the battlefield has ballooned to include, well, almost everything, from holiday greetings to beer.

Thirty years later, the culture wars are heating up again, fueled by the power and reach of social media and the ascent of transparency as a core value. When every public meeting can be livestreamed on Facebook by anyone in the audience, there is scarce opportunity for nuanced discussions that can explore compromise and de-escalate conflict. Social media is now a major source of information for Americans, and given the decline of professional journalism, it is often the primary platform for people to engage with current events.

The current state of P–12 education dramatizes the damage these conflicts can do to civic infrastructure. Teachers, already stressed by pandemic challenges, are barraged with complaints from parents and students about every detail of their work, including curricula, assignments, classroom decorations, and off-hand remarks. Even minor conflicts can go viral, spiraling into public campaigns calling for educators to be disciplined or fired. This relentless scrutiny has contributed to record-high levels of teacher burnout and turnover, to the migration of students from public to private schools and to homeschooling, and to the downsizing and closure of school libraries.

These skirmishes are egged on, in part, by those that profit from amplifying conflict: politicians courting votes, journalists seeking readers, technology corporations building reach and engagement. But they also reflect real disagreements in society about what theologian John Davison Hunter calls “matters of ultimate moral truth,” things on which one cannot compromise. Many combatants see the issues as threats to their very existence: white nationalists fear they are being replaced by people of color; trans individuals fear erasure of their identities and their lives. Stable democracy requires compromise, but negotiation around existential issues, about what is moral and ethical, seems impossible.

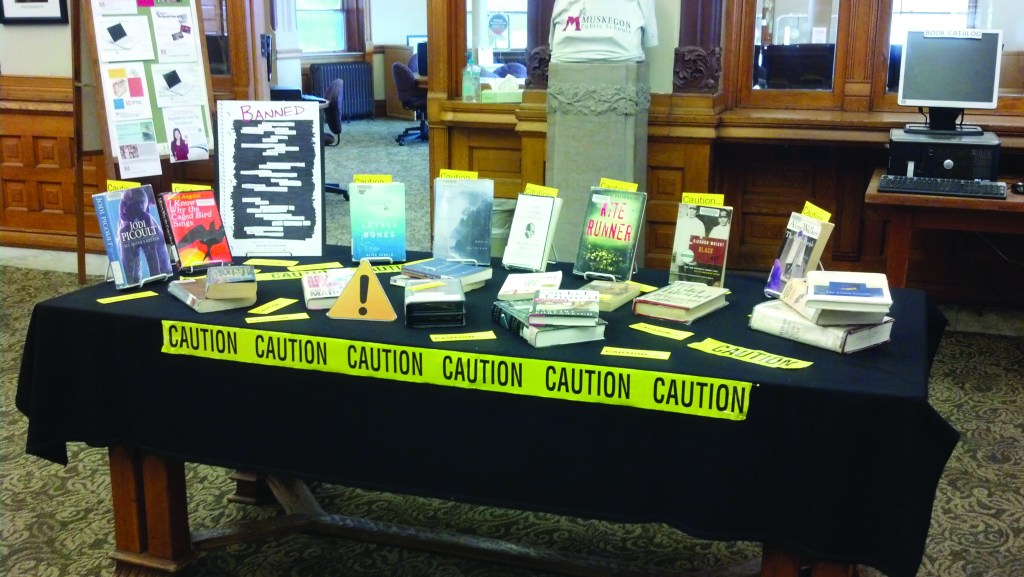

While cultural nonprofits have long been drawn into this fray, they are now being targeted with particular vitriol. America’s public libraries (a system built with the largesse of Republican Andrew Carnegie) have become flashpoints for protests and penalties around progressive actions and values. We are seeing a record number of attempts to ban books, criminal complaints against and laws targeting librarians, and attempts to defund and close libraries. The American Library Association itself is now being attacked, nominally over the politics and identity of its CEO but more broadly over its support for and defense of its members. (This despite the fact that, as the ALA points out, there is strong nonpartisan consensus about the value of libraries and librarians.)

One drawback of using the term “culture wars” is the implication that there are two clear sides arrayed against each other, but that framing is inaccurate and unhelpful. Both liberals and conservatives drastically overestimate the difference between their views and those of the other side while underestimating the difference in views within their own side—a phenomenon dubbed “false polarization.” In fact, subgroups within political parties are complex and varied. (For example, the vast majority of Black voters are Democrats; 61 percent of Democrats believe a person’s gender can differ from the sex identified at birth; only 31 percent of Black Democrats agree.) And while there are intransigent differences of opinion, there are also areas of broad agreement: 9 in 10 Americans believe that protecting free speech is an important part of American democracy, and people should be allowed to express unpopular opinions.

Another problem with framing these conflicts as a war is the implication that there can be a winner. Short of a “national divorce,” splitting Democrat- and Republican-leaning states into different countries (an option that is, in fact, supported by 20 percent of US adults), we have to find a way, as a society, to explore these differences openly, honestly, and with respect if we are to maintain a functional democracy. Making people aware of these areas of commonality might be the best hope for reducing false polarization. Perhaps, as the growing bipartisan civic repair movement recommends, instead of focusing on changing people’s views about issues, “we need to change their views about each other.”

What This Means for Museums

This isn’t the first time museums have been caught up in partisan struggles. Buchanan’s speech in 1992 helped define a decade of controversies that included criminal indictments against the Cincinnati Contemporary Arts Center on obscenity charges stemming from an exhibition of photographs by Robert Mapplethorpe; outcry over the Smithsonian’s interpretive plans regarding the B-29 Superfortress bomber Enola Gay (a resolution passed by the US Senate characterized the exhibit script as “revisionist and offensive to many World War II veterans”); and Mayor Rudy Giuliani threatening to defund and displace the Brooklyn Museum of Art because of the “sick stuff” on view in “Sensation: Young British Artists from the Saatchi Collection.”

These attacks come from the right and the left. Where Culture War 1.0 was fueled by the rise of the Moral Majority and other religious conservative movements, today’s culture war engages the progressive left as well as the conservative right. It includes movements like Black Lives Matter, #MeToo, and LGBTQ+ activists—groups that want greater inclusivity and a greater sensitivity to harm, historical trauma, and legacies of exclusion and appropriation.

They also originate from inside and outside the organization. One source of tension is the fact that museum staff are overwhelmingly liberal, while boards and donors often skew conservative. This can complicate decisions around what topics the museum should address and what communities it should serve. In some instances, museum staff have called for their employers to cancel space rentals by conservative groups, distance themselves from objectionable donors, and remove exhibit material they found offensive. With increasing frequency, climate activists are using museums as platforms for protest, throwing paint on or gluing themselves to frames, vitrines, or the plex protecting iconic objects to draw attention to their cause.

Some of the public’s strongest reactions are prompted by museums revising their interpretation of history. Monticello and other historic sites have been castigated by some visitors and conservative commentors for introducing slave narratives into their interpretations. Texas is embroiled in a messy fight over how to tell the story of the Alamo, which has been called the “creation myth of Texas.” Myths, especially when they amplify an inaccurate version of the past, can be toxic: perpetuating those inaccuracies, justifying past actions that caused harm, and over-amplifying the anti-inclusive values of a small (but politically powerful) segment of Americans. But any identity, individual or collective, is grounded in the stories we tell about ourselves. Can America have a unified national identity without shared stories we all buy into? Without that identity, will the country tear itself apart?

Ironically, the very respect accorded to museums, as stewards of culture and trusted sources of information, may amplify these pressures in the future. In the wake of protests over the murder of George Floyd in 2020, at least 200 Confederate memorials were removed, renamed, or relocated, and in many cases these monuments were transferred to museums. While the intent may have been a bipartisan solution (caring for the heritage in perpetuity while providing historical context), this approach is sometimes equally offensive to people who feel these objects should be destroyed and to those who object to “revisionist history.” With many schools abandoning controversial topics, museums may pick up the slack, just as they did over a decade ago when public schools largely abandoned arts education. But while arts education is generally seen as benign, topics such as race and racism, gender and sexuality, and controversial social and political issues are not. Some schools have reached out to museums to teach subjects they feel they can no longer handle. Will the outrage follow?

How can museums stay true to their role and their values without being sidelined by one faction or another? How can they retain bipartisan or nonpartisan credibility and influence while tackling difficult issues? Museums have the potential to foster healing or inflict harm, build bridges or deepen divides depending on how they respond to these challenges, but they face difficult choices. Museums might take stands on issues that align with their mission and the values of staff and stakeholders. They might declare themselves to be noncombatants, serving as a cultural circuit breaker for the cycle of escalating outrage. They might play the role of peacemaker, helping people find common ground.

Each of these choices comes with potential benefits, and risks. Museums have earned broad, nonpartisan trust from the American public, and they can use that trust to educate and influence the public about important issues. On the other hand, taking a stand on contentious issues may result in a particular museum, or museums as a whole, being tagged as partisan, relegated to the echo chambers of people who already agree with them. The individuals and institutions that benefit from the culture wars thrive on public attention: perhaps sometimes museums might better serve vulnerable individuals, communities, and society as a whole by refusing to engage. But people who feel targeted by these conflicts may expect museums to weigh in with a statement or action that signals solidarity and support. Museums have long aspired to be public “agora” where people can come together to discuss important issues without feeling the need to self-censor. To ensure that people of all political identities feel welcome in these conversations, the museum itself might need to be seen as nonpartisan—neither liberal nor conservative—in its words and its actions.

Everyone loses when cultural and educational institutions are damaged by partisan skirmishing. Treating libraries, museums, and schools as active combatants in the culture wars destabilizes our already fragile social infrastructure by threatening some of the few remaining institutions trusted to provide accurate information and common reference points.

In his exploration of the culture wars, Hunter also observed that “the whole point of civil society … is to provide mediating institutions to stand between the individual and the state, or the individual and the economy. They’re at their best when they are doing just that: They are mediating, they are educating.” By engaging in hard conversations, inside their organizations and with their communities, museums can continue to fill that critical role.

Potential Future Battles

Following are some challenges posed to museums by the ongoing culture wars in the coming decade:

Consumers have more choices than ever in how to engage with history, culture, and educational content. Will museums lose out if, as just one choice in this array, they are identified as affiliated with one set of political positions or another?

There are growing disconnects between the expectations of some major foundations and those of local, state, or federal government officials (for example, regarding training and policies supporting DEAI). How will museums navigate these tensions and other partisan issues that may affect funding, whether that support comes from public dollars or individual donors?

There are significant generational divides around many contentious issues today, and around expectations of how organizations should behave. How can museums respond to the concerns of both current and future audiences?

We have recently seen high-profile boycotts of brands (Bud Light, Chick-fil-A) and institutions (Walt Disney World) from the left and the right. In the future, might we see partisan boycotts regarding museum attendance and membership?

Will more activists begin to use museums as useful platforms for protest, deploying vandalism against objects, or violence and threats of violence to draw attention to their causes? How would that change operations—design, staffing, procedures—and how might tighter security make some people feel more, or less, safe and welcome?

Museums Might …

- Lead thoughtful, intentional conversations among board, leadership, and staff about their own values and how the museum should choose to engage or not engage on culture war issues.

- Establish frameworks and procedures for evaluating exhibits, programs, and event rentals for potential controversies, and create plans for how these controversies will be managed.

- Evaluate the language used in exhibits, programming, and communications. Identify partisan trigger words, and, when possible, find alternative terminology. (For example, some museums have found it is less controversial to say “our changing climate” rather than “climate change.”)

- Train staff on how to have difficult conversations with people who don’t share their beliefs and how to facilitate these conversations with others.

- Create policies, procedures, and training that equip staff to deal with angry or confrontational members of the public, and offer support to help them cope with the resulting stress.

- Strive to be “third places,” the increasingly rare venues that sociologist Ray Oldenburg has argued are vital to society, democracy, and civil society. By welcoming people of differing backgrounds and beliefs, museums can provide opportunities for them to socialize and get to know each other as individuals.

- Monitor legislation and legal decisions that can affect their operations, even when not directly aimed at museums, and address these issues in their advocacy. (Sign up for Advocacy Alerts and attend AAM’s annual Advocacy Day to inform this work.)

Museum examples

Taking a Stand

In June 2023, the Museum of Us hosted “Party With Us: Pride Edition,” a day of programming featuring San Diego drag queens from the Haus of St. James, in solidarity with LGBTQIA+ communities being inundated with hate and legislative efforts to undo hard-won civil rights protections. Despite the polarizing public debate on drag, the decision to host the event was consonant with the museum’s purpose to be a place for community voice, especially those voices that have been historically marginalized. This was consistent with the museum’s previous visible support of LGBTQIA+ communities. In 2015, immediately following the Supreme Court’s decision on same-sex marriage, the museum displayed an enormous Pride flag from its iconic California Tower to mark the occasion. Since 2022, the museum has also been the site for the city’s annual Pride kick-off, with a week-long display of an even bigger Progress Pride flag from the tower.

Being Noncombatants

By its very nature, successful noncombativity is a nonstory. While this makes it rare to find published examples of museums that have chosen not to “feed the beast,” museum professionals might use the confidentiality afforded at conferences and small gatherings to connect with colleagues who have personal experience to share.

Playing Peacemaker

In 2019, the Frazier History Museum in Louisville, Kentucky, launched “Let’s Talk: Bridging the Divide,” creating a flourishing community space for dialogue and questions on challenging topics that often divide us. The program’s name ties to the Frazier’s location on the so-called “9th Street Divide” that historically has separated the city by race. Through dozens of moderated panel discussions, the museum has given the public an opportunity to hear from guests with varying perspectives on wide-ranging and sometimes contentious issues, including mental health, political discourse, voting, racial equity, policing, education, and Native American history. One of the most recent programs was the first community conversation about a newly released report from the US Department of Justice critical of policing in Louisville. This groundbreaking gathering brought together the mayor, the acting police chief, and representatives from the NAACP, Louisville’s Urban League, and the Fraternal Order of Police. The museum staff who facilitate the programs observe, “The dialogue isn’t always easy, and navigating the discussion and audience questions can be tricky, but if you want to bridge divides, there has to be conversation.”

Resources

Crisis Communications Guide, American Library Association

This brief guide outlines how to put a communication plan in place before a crisis occurs. ala.org/advocacy/crisis-communications-guide

Marketing Intelligence Hub, Listen First Project

This online resource shares data-driven guidance on how to communicate in a way that fosters interest, hope, and trust from Americans of all backgrounds and beliefs. listenfirstproject.org/marketing-intelligence-hub

Respecting Visitor Values: Audience Perceptions, 2022 Annual Survey of Museum Goers, Wilkening Consulting

This data story picks apart three main criticisms offered by the small percentage of museum-goers who do not believe that museums respect their personal values. (These categories correlated tightly with political values.) bit.ly/RespectingVisitorValues