Have you ever been in a meeting and thrown out an idea, only to have a colleague start listing all the reasons it won’t work? Or maybe you’ve thought of one in your head, only to second-guess yourself and shut down your own thinking? These are all-too-common scenarios that can stifle innovation in many institutions, but the good news is they can be avoided by leveraging a framework called the Double Diamond and its core premise of divergent and convergent thinking.

Put quite simply, the reason behind the tension in the above scenarios is the clash between a “divergent” thinking mode, where you’re trying to imagine and explore all possibilities, and a “convergent” thinking mode, where you’re trying to narrow down and analyze the options. And you can’t be successful if you’re in both modes at the same time. The Double Diamond proposes that we must separate the generation of ideas from the selection of ideas if we want to effectively solve the right problems and arrive at creative solutions. Trying to diverge and converge at the same time is like driving with the brakes on. And when you drive with the brakes on, you won’t get very far.

From developing new visitor-centered offerings to redesigning museum staff meetings, using the Double Diamond can save museum professionals time and frustration, and can inform the way we work and collaborate inside our institutions and with our communities.

What’s the Double Diamond?

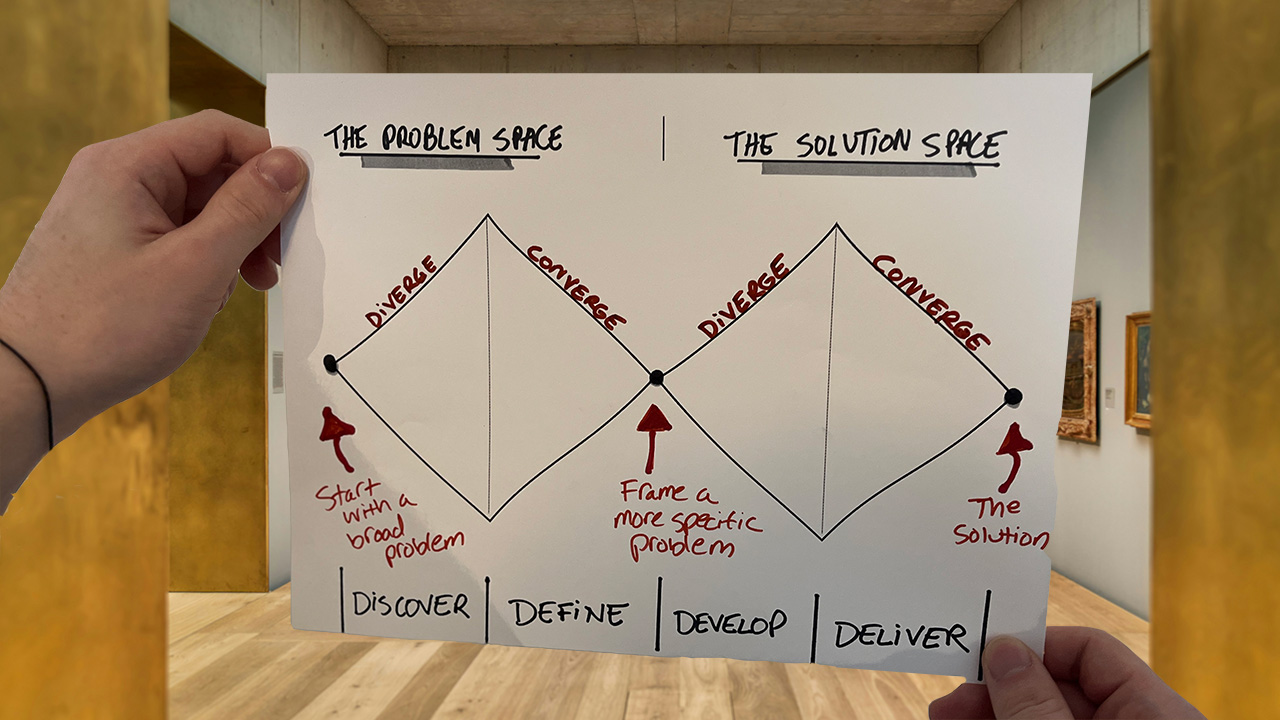

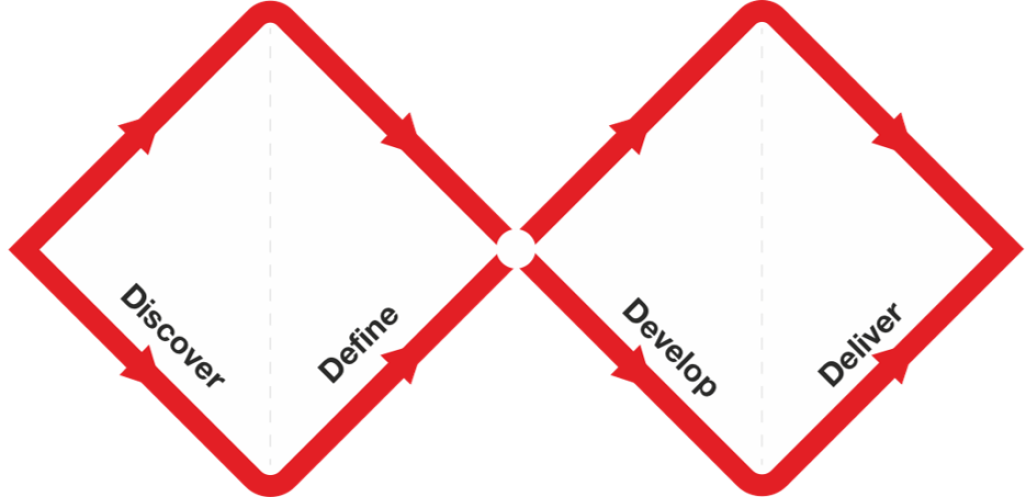

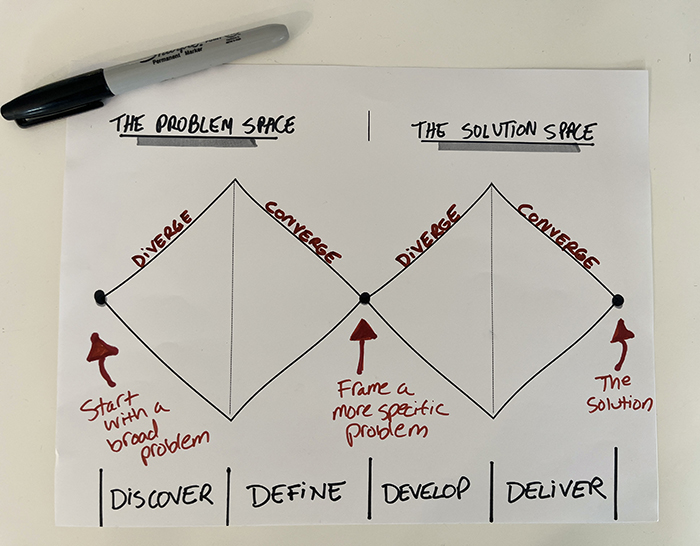

The Double Diamond is a visual representation of the design and innovation process and provides a common language and process for problem-solving and innovation. In this case, “design” refers not just to exhibition development or visual design, but to the broader concept of human-centered design: a discipline for creative and collaborative problem-solving in the service of people. Human-centered design involves working iteratively to make things better for people, whether the thing is a public program, the visitor experience, or a museum policy, and whether the people are visitors, community members, or staff.

When properly applied in museums, the Double Diamond can help teams effectively understand problems, imagine possibilities, and prioritize solutions. It supports iterative testing and refinement of ideas, ensuring that final concepts are well-tested and aligned with your museum’s mission and visitor needs.

“[The Double Diamond is] not an instruction manual on how to design, it’s an invitation to get involved.”

– Tim Browne, Co-Chair at IDEO

The Double Diamond emerged from rich historical practices in the Creative Problem Solving Community and the work of Alex Osborn (1888 -1966) and Sid Parnes (1922-2013), among others, and was popularized some twenty years ago by the British Design Council.

While there is a recent evolution of the Double Diamond into a newer framework that focuses on sustainability and the impact on the planet, for the purposes of this post, I’ll be focusing on the original version. I believe that its depiction of “important root behaviors known as divergence and convergence” are especially critical for museum professionals to leverage.

What Are Divergent and Convergent Thinking Modes?

Underpinning the Double Diamond is the core premise of divergent and convergent thinking. When we follow the Double Diamond framework, we work in successive cycles, intentionally alternating between divergent and convergent thinking.

Divergent thinking is generative, exploratory, and creative—it’s about opening up, learning more, and imagining lots of options. It asks us to be receptive to discovering new possibilities and to hold off on judging, making decisions, or jumping to solutions. At the Stanford Hasso Plattner Institute of Design, or d.school, where I was first trained in human-centered design, it’s commonly referred to as “flaring.”

Convergent thinking, in contrast, is analytical, focused, and conclusive. It’s about narrowing down, making choices, and evaluating. This is what the d.school refers to as “focusing.” This is where most people naturally go when faced with an ambiguous situation.

What Does This Mean for Museum Professionals?

As museum professionals, we’ve been trained to solve problems as efficiently as possible and do excellent work with limited resources. This means that convergent thinking is a common go-to, as we strive to arrive at solutions as quickly as possible. But this can cause friction when we are at a point in the process where divergent thinking would serve us best.

For example, imagine someone in a meeting describing a problem that a recent online visitor had with the website. Most of us would likely jump right to suggesting a “fix” or solution to the problem, rather than spending any time in the “problem space” to learn more and explore the range of options. While this may yield an efficient temporary solution, there is probably an opportunity here to explore and develop other solutions.

While the default to convergent thinking might sound logical (aren’t we all conditioned to quickly solve problems?), it doesn’t make space for nuanced insights or breakthrough ideas. And it creates friction when teams are focusing and flaring at the same time.

The Four Phases: Discover, Define, Develop, Deliver

This is where the Double Diamond, with its phased approach, can inform problem-solving and reduce friction. With its four phases, which are described below, the Double Diamond signals when to transition between divergent and convergent thinking, helping teams arrive at the best outcome.

Here’s how it works.

1. Discover: Understand what the problem is by understanding the people affected by the issues.

Imagine that a current challenge your museum is facing is how to best serve visitors who have never before visited your institution.

You might set out with a general problem frame, such as, “How might we best serve our first-time visitors?” You would start in the Discover phase by diverging. At this point, you do not seek to make any choices about what you will develop for these visitors, but simply to better understand them. For instance, you might begin with research activities such as interviewing and observing visitors.

2. Define: Leverage insights to refine and refocus the problem.

After you’ve diverged and gained insights on the people and the situation, you then enter the Define phase and use convergent thinking. This is when you synthesize your data, develop insights, and reframe the original problem into something more specific. You are still in the “problem” space, meaning you’re not yet coming up with solutions.

For example, if one of your insights from the Discover phase was that first-time visitors feel overwhelmed when they first walk into the permanent collection galleries, you might reframe the problem as, “How might we help first-time visitors to not feel overwhelmed when they first walk into the galleries?”

Or, if an insight was that many first-time visitors feel stressed because they say they “are not art people” (a real insight from a past project I worked on with an art museum), you might reframe the problem as, “How might we re-assure first-time visitors they don’t need a PhD to enjoy the museum?”

You have taken a broad problem—“How might we best serve first-time visitors?”—and reframed it. Now you’re finally ready to enter the “solution space.”

3. Develop: Imagine all potential solutions.

Now we enter the Develop phase and diverge again, imagining all potential solutions. This is what most people call brainstorming or ideation; it’s about coming up with lots of ideas. We are not (yet) worrying about what they will cost, how difficult they will be, or what is viable. Going with the analogy of driving, we are not yet using the brakes.

At this point, it’s common for people to fall back on self-editing their ideas, critiquing while they are brainstorming, essentially shutting themselves down. But it’s important to resist this impulse. An idea that seems outrageous, wild, or totally unrealistic may lead us to an innovative, breakthrough idea, even if it takes some tweaking to get there. If we limit our thinking and try to converge at this point, we’re more likely to come up with obvious and safe ideas.

4. Deliver: Make choices, test, and iterate.

After you have generated and captured lots of ideas, it’s time to converge again and make hard choices, assess, and evaluate. This is the Deliver phase, when we select the ideas we want to pursue. We might consider how well each idea we’ve generated aligns with the mission statement, institutional values, or current strategic priorities, and what resources would be required for implementation. This is when the rubber meets the road and trade-offs must be made.

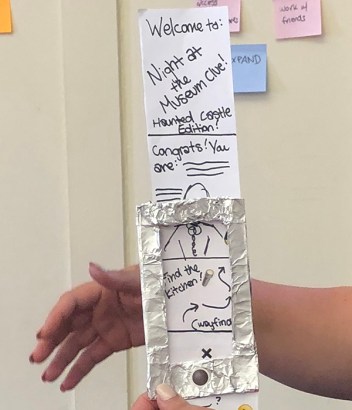

After we’ve selected which idea or ideas to move forward, we start prototyping and testing potential solutions. This can take the form of paper mock-ups or experiential prototypes. While the traditional graphical representation of the Double Diamond depicts only two diamonds, there can actually be subsequent “mini diamonds” within the Deliver phase, in which we diverge and test prototypes with real visitors, and then converge on the best options and features for our final offering.

Conclusion

While originally applied to business applications and consumer products, the Double Diamond and its modes of divergent and convergent thinking are broadly applicable and highly beneficial for internal collaboration and creative problem-solving within museums.

By applying the Double Diamond to museum work, museum professionals can navigate complex challenges through a phased process of discovery, definition, development, and delivery, ensuring a thorough understanding and exploration of problems before jumping to solutions. The Double Diamond not only enhances internal collaboration, but also leads to more impactful offerings. Its adaptability to different challenges makes it a valuable model for institutions seeking to improve or redesign programs, processes, experiences, or products.

Ultimately, the Double Diamond teaches the value of embracing both generative and analytical modes of thinking to foster a culture of human-centered design and creative problem-solving within the museum sector.