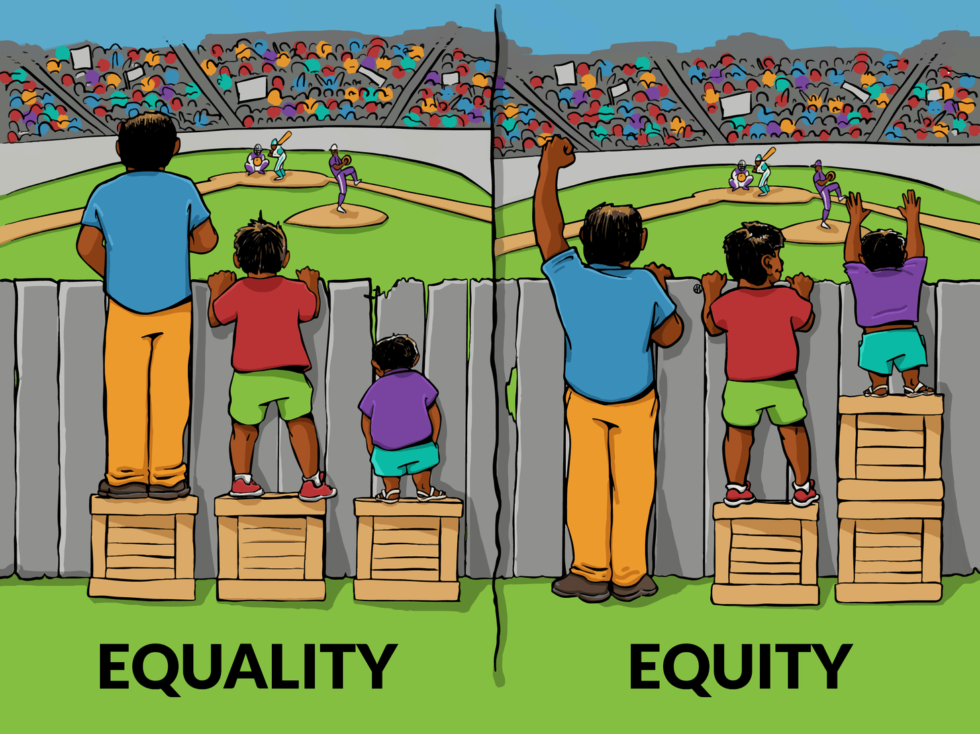

Do you remember seeing this picture attempting to illustrate the difference between equality and equity?

Now it also illustrates the latest battleground in the new culture wars. While a whopping 91 percent of Americans agree on the importance of equality under the law, this consensus centers on opportunity, not outcomes. A 2023 Pew poll, for example, found 78 percent of workers who identify with Democrats consider increasing diversity in the workplace a good thing, while Republican workers are evenly split (30/30) between considering it a good or a bad thing.

Capitalizing on this gap, a small group of political activists are reframing DEI as discrimination against white people (particularly white men). They are using this framing to bring legal challenges against DEI actions, citing civil rights laws intended to protect groups historically disadvantaged by race or gender to attack any programs intended to preferentially benefit those groups.

Basically, they are arguing that, in the classic picture illustrating equity versus equality, adding an extra box to boost someone over the fence is illegal.

Unfortunately, this tactic has been pretty successful. Its biggest victory may be the Supreme Court ruling, last June, prohibiting universities from explicitly considering race in the admissions decision-making process. The defendants, Harvard University and the University of North Carolina, argued they could lawfully consider an applicant’s race, but while the Court acknowledged the goals of these programs are commendable, they ruled that the actual policies failed a number of specific legal tests. In the wake of this decision, colleges and universities across the country have raced to reshape their application processes, while finding new, legal strategies to foster diversity in the student body.

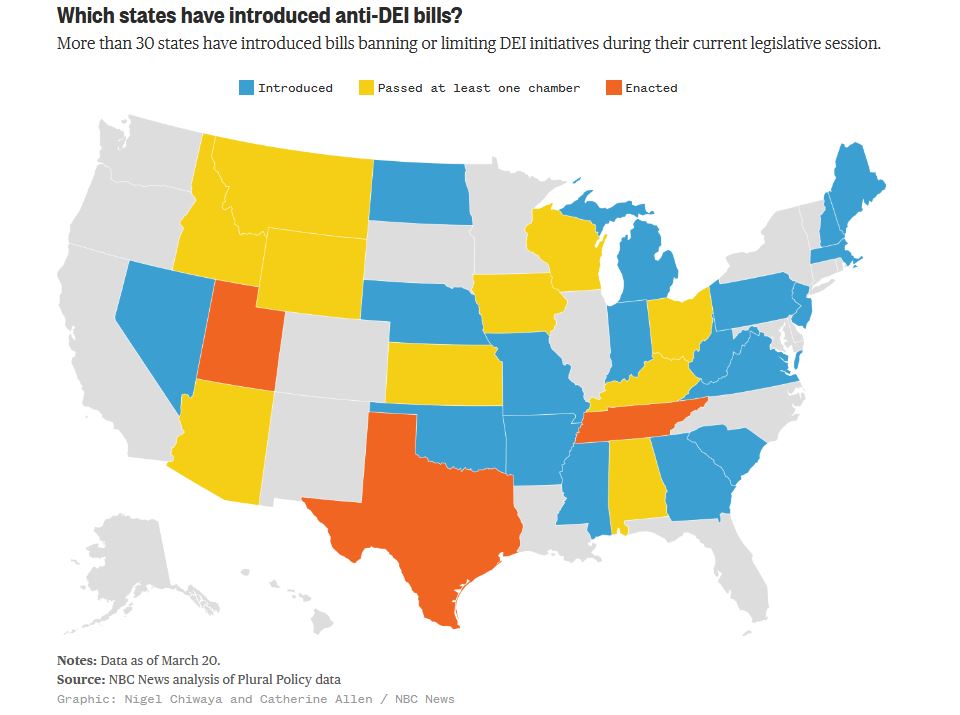

Nine states, including Alabama, Florida, Indiana, North Carolina, North Dakota, Tennessee, and Wyoming, have passed laws banning or restricting DEI efforts at state organizations. (For context regarding the impact of such laws on our field, about 10 percent of museums fall under state governance.) Last month, Utah State University announced it was renaming its Office of Inclusion and Diversity, now the Office of Institutional Engagement and Effectiveness, to comply with Utah HB261. The law bans schools (colleges, universities, K-12) from having an office that uses the terms “diversity, equity, and inclusion” in its name. These institutions are also now barred from requiring applicants to sign any statements related to diversity as a condition of hiring. In the wake of Texas Senate Bill 17, the University of Texas has laid off at least sixty staff members who had worked in DEAI positions.

Just as book bans in libraries presaged similar attacks on museums, the impact of DEI backlash on higher education signals what may be in store for American museums. In fact, that impact is already beginning to be felt:

- In 2023, former slave plantations, operated as historic sites by the Texas Historical Commission, removed a number of books from their stores—most by Black authors, many addressing racism, and one, Remembering Days of Sorrow, a transcription of oral histories collected through the WPA Slave Narratives project. According to an investigation by a Texas publication, these titles were removed in response to complaints from the founder of a nonprofit advocacy group that advocates for “fact-based history.”

- In January, the Anchorage Museum announced it would offer free general admission to Alaska Natives, as part of its commitment to strengthening relationships with Indigenous communities, and received criticism that the policy was “discrimination against non-Alaska Native visitors.” The policy was placed on hold to receive additional legal review.

- In February, the American Alliance for Equal Rights sued the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Latino, alleging that the museum’s internship program practiced “pro-Latino discrimination.” The museum settled the lawsuit last month, after agreeing to add a statement on the internship application stating the opportunity is “equally open to students of all races and ethnicities.”

While for the most part this backlash has been directed against diversity, equity, and inclusion, it may also have a chilling effect on accessibility, both generally and perhaps specifically. Generally, because accessibility for people with disabilities is often bundled into diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts, so laws that target DEI may inflict collateral damage on accessibility.

We may see specific challenges as well. One early signal: Last month a forty-year-old baseball fan sued the Washington Nationals for offering discounted tickets to millennials, arguing it constituted age-based discrimination. (The team suspended the discount while the case goes forward.) While the Nats’ incentive was aimed at cultivating younger audiences, senior discounts for a wide variety of services (including museum admissions) can offer economic accessibility to elders on fixed incomes. What other groups could this impact? What about free admission for infants or toddlers to make family visits more affordable? Or free admission for SNAP recipients under the Institute for Museum & Library Services’ Museums for All program?

Given the stories related above, the DEI backlash might seem like a broad-based, grassroots reaction. In fact, however, research suggests that a very small set of voices are using extreme views to exaggerate and amplify divisions. Most of the current high-profile legal challenges have been brought on by a small number of well-funded groups, but they help create the perception that we, as a society, are radically divided on these issues. This perception may be an example of what Harvard neuroscientist Todd Rose calls a “collective illusion.” When people really get to know each other, they find they agree on far more than they expected. The nonpartisan think tank Populace is making a data-based case that our efforts would be better spent on illuminating and exploring these points of overlap, rather than digging in, hardening our armor, and doing battle over our differences. Many argue this is how we arrived at a national consensus, and federal legislation, recognizing same-sex marriage, for instance.

The current DEI backlash depends on the belief that, given equal opportunity, people succeed or fail on their own merits. This worldview does not acknowledge that differences in outcome can be the result of past inequities, or of biases baked into our systems that have not and perhaps cannot be addressed by the law. Understanding those historic and systemic sources of inequity, combined with a shared sense of fairness, might increase support for reparative practice, in order to truly level the playing field. Unfortunately, educational institutions, from kindergarten through higher ed, and libraries, are under attack for teaching or providing the content that could create that understanding. That makes it more important than ever that museums keep teaching history and fostering understanding of our complex world.

And the broad, nonpartisan trust that the public affords museums gives our sector the potential to have this influence—if we can avoid losing that trust. Higher education has been tagged and marginalized as liberally biased. It will take thoughtful strategizing to ensure that museums, individually and collectively, don’t find themselves in the same situation.

What does that mean, operationally? What actions can a museum take, at the board and staff level, to ensure they retain their ability to build bridges, and not provide easy targets for extremists looking to score points? Here are a few suggestions I’ve collected in conversations with directors and staff grappling with difficult situations:

- Consider your language. Society is engaged in a high-speed Red Queen’s race, in which terms are turned into shibboleths or dog whistles tagging content as unacceptable. DEI itself is a prime example. Museums are finding that social-emotional learning, climate change, and even civics and civil society are being characterized as partisan. (Also on the horizon, the 250th anniversary of our country—is it a “celebration,” or a “commemoration”?) Susie Wilkening, of Wilkening Consulting, calls this “definition creep,” and points out we can either keep finding new ways to say what we mean, or stand up for our terms as non-partisan tools. (Either tactic, she concedes, is exhausting.)

- Review your policies about space rentals. In my scanning file, more than a dozen stories tagged with the term “controversy” involve partisan uproar over events staged at, but not by, the museum, whether those groups are on the left or the right.

- Ditto policies regarding what visitors can wear or bring into the museum—whether that’s to ensure cultural and religious practices are respected or to mitigate hate speech. Once you are confident the policies are sound, make sure staff are trained to enforce them consistently and with grace.

- Think about what issues the museum will or won’t make statements about, or whether it will make statements at all. As an article in the Chronicle of Philanthropy noted last fall, “Experts in fundraising and communications are advising nonprofits to rethink making statements about national politics and world affairs and craft coherent policies that ensure they’re sticking to their core mission.” Data from a broader population of US adults, fielded as part of the 2023 Annual Survey of Museum-Goers, showed that about 40 percent of US adults supported museums making statements on issues (such as anti-racism, Indigenous land acknowledgments, condemning violence) so long as it relates to the museum’s mission. Another 40 percent either felt it was important for museums to do (regardless of mission), or, though they hadn’t thought about it, were glad to see museums issue such statements. However, it’s worth remembering that having issued any statement, a museum may well come under pressure, internal or external, to speak out on other issues as well—whether or not they are mission-related, and whether or not there is consensus, among staff and board, around what position the museum should take.

Finally, I wonder if museums might get ahead of the curve by explicitly including political views in the categories protected by their own DEI policies. This wouldn’t mean forcing people to self-identify their political views, any more than current DEI programs make people disclose other aspects of themselves they feel are private. It would mean creating a safe environment in which people feel they can bring their “whole self” to work, which may, for some people, include values and views that inform their identity as a voter. Uncovering potential areas of agreement involves people knowing people from “the other side,” working and socializing with those who vote differently. Understanding their humanity, and the values underlying their choices (their articulation of those values, not labels affixed to them by others) can be powerful ways to cultivate empathy and find common ground. Something to think about.

I find this article incredibly dishonest. DEI initiatives have propagated racism, albeit unintentionally by most and taken advantage of by race-baters, as it favors people of color with marginalized backgrounds over people born with white skin regardless of merit and ability. It has refocused certain groups to view the supposed dominant white culture as bad and oppressive while ignoring the reality that all groups have participated in and been victims of oppression in the past. While it should foster equality across the board, it does not do that in practice. The only way to stop racism is to not consider race in decisions. DEI also assumes that people of color and people considered marginalized aren’t capable of performing and therefore need a boost, which is hugely racist. These programs were intended to help but are only fostering the thing they are trying to cure.

I also meant to say that I really think including voices from many different people with varied perspectives is a good idea as it expands the experience and includes a well rounded overall vision. I just despise the oppressed vs oppressor narrative that has taken over every conversation. While it plays a part, it is not the only thing to talk about in history.

You should have excluded your final sentence, “Something to think about.” By including it, you weakened the strength of your otherwise well-reasoned, balanced argument about including all political views in DEI policies, not just the left-tilted worldview of your target audience. Without your final sentence in place, your blog post had the opportunity to close in a strong way that challenged the biased view of your target audience to push them up to a higher, more inclusive level of intellectual thought and discourse. Instead, your final, throw-away sentence was you privately admitting to yourself – but putting it in writing for all the world to see – that the probability of this target audience ever reaching such a higher level of intellectual thought and discourse is pretty darn low. Something to think about.