This article first appeared in the journal Exhibition (Spring 2024) Vol. 43 No. 1 and is reproduced with permission.

Solutions to climate change exist. We have the knowledge. We have the technology. What is required now is the human-powered collective action to implement solutions globally and with social justice in mind at every step. This is the central message of Project Drawdown, a nonprofit organization focused on “advancing effective, science-based climate solutions and strategies; fostering bold, new climate leadership; and promoting new climate narratives and new voices.”[1] Project Drawdown was the inspiration for The Wild Center’s Climate Solutions exhibition, a new permanent exhibition that opened in July of 2022 (fig. 1).[2] The Wild Center, a natural history center in Tupper Lake, New York, has been working in programmatic climate education for over a decade, but, until Project Drawdown, we could not envision our climate work in exhibition form. Project Drawdown’s solutions-based framing shifted our outlook, inspiring us to seek out and profile the changemakers in our local community–because that is where all change will occur, in the trenches with our sleeves rolled up. Climate changemakers are our friends and neighbors in the rural Adirondack community in upstate New York.

The challenge for the exhibition team was if (and how) we could leap over the fear-inducing facts of climate change and embrace an alternative reality where we are already on the road to solving the problem and everyone is inspired to join in with their own self-defined action. To keep the focus on solutions, we needed to test the assumption that we did not have to devote any of the exhibition’s real estate to convincing our audience that the science is settled.

Getting to Know Our Audience

As we began planning and preparing for exhibition development, we reflected on our hunches about the “typical” Wild Center visitor. We needed to consider who we were trying to reach with an exhibition about climate solutions, so that we could tailor our tone and approach. The exhibition team suspected that while many who come to The Wild Center appreciate learning about and engaging with nature, they may not necessarily be attuned to or concerned about climate change. How much groundwork, or even convincing, would be needed to introduce visitors to the climate crisis and to the notion that solutions exist and are already underway?

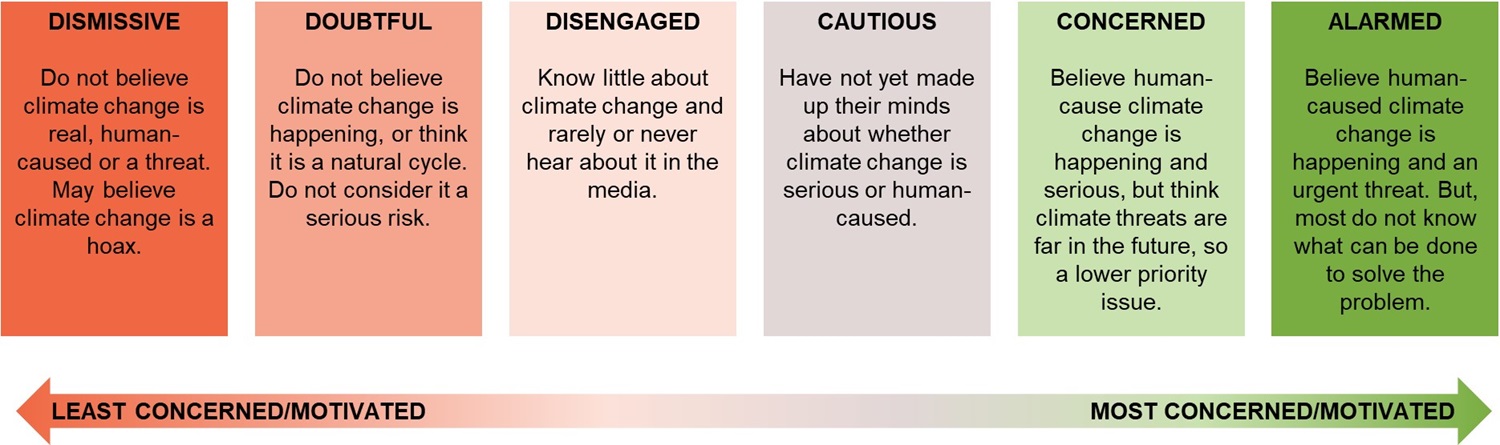

The Wild Center decided to work with museum evaluation firm Kera Collective to conduct front-end research that would test our assumptions. Together, we decided to draw from a body of public perception research by Yale University’s Program on Climate Change Communication (YPCCC). Using the Six Americas Super Short Survey, or SASSY, developed by the YPCCC as a starting point, we began to try to better understand our visitors.[3] The SASSY asks four simple multiple-choice questions, which allow researchers to segment respondents into one of six audiences, ranging from dismissive to alarmed, based on their climate attitudes (fig. 2).

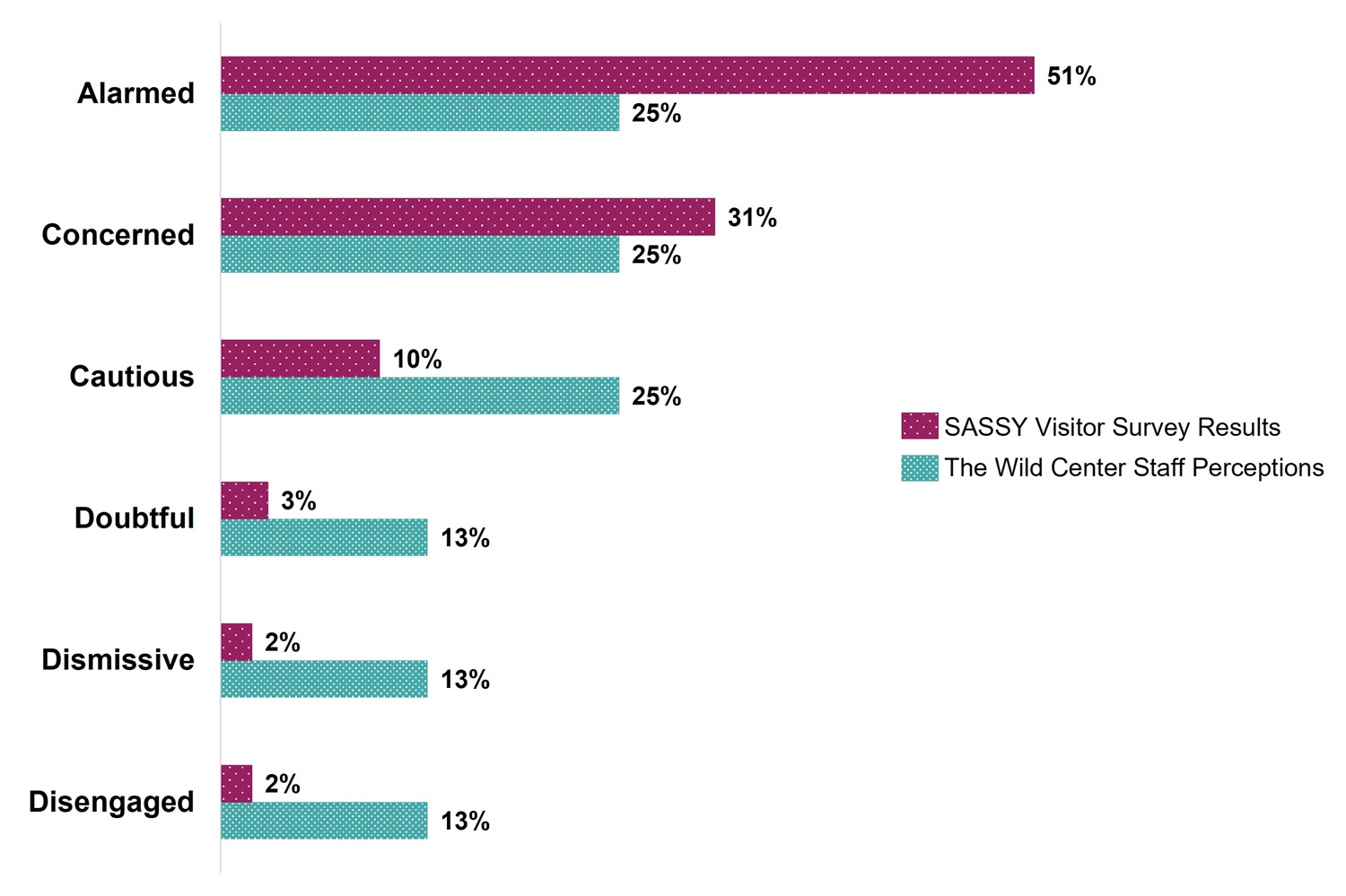

As a first step, we shared the SASSY audience definitions with staff and asked about their perceptions of where The Wild Center’s visitors would land on this spectrum. Serendipitously, The Wild Center had begun collecting visitor email addresses for all online ticket sales during the pandemic. As a second step, we used this list to contact a random sample of museumgoers who had visited during the summer and winter of 2021 and asked them to complete the short survey, receiving 277 responses.

The results were a revelation! Staff members’ assumptions about our audience’s stances on climate change were substantially different from reality (fig. 3). Wild Center staff thought most of our visitors would be a relatively even mix of Alarmed, Concerned, and Cautious audiences, respectively, with small proportions of Disengaged, Doubtful, and Dismissive as well. In reality, over 80 percent of visitors who responded to the survey were Alarmed or Concerned, meaning many more were highly concerned about climate change than we anticipated.

Setting a Course for Exhibition Design

The exhibition-development team used the results of this front-end research to focus in on the target audience for the exhibition. Knowing that most of our visitors were already Alarmed or Concerned allowed the exhibition team to confidently make the decision not to target visitors who fell into the Cautious audience segment or below. Our survey results suggested that these segments represented only a small percentage of our audience; moreover, YPCCC’s own research shows that individuals in these segments are less likely to be convinced to engage in climate actions in any case.[4] We resolved that those looking for the climate science could find it elsewhere in the museum, in our Science On a Sphere programming, for example, or in a new film, The Age of Humans, which focuses on clear communication around the science of climate change and climate impacts in the Adirondacks. This freed Climate Solutions to focus on reaching the Concerned and Alarmed with the big idea:

People across sectors, generations, and backgrounds are building a web of climate solutions and are inviting all of us to find our place in the climate movement.

Now, we could focus fully on exploring the solutions-framing that would be most effective in the exhibition for presenting challenges and linking them to actionable solutions and positive outcomes. We knew from the SASSY audience profiles that people who are Alarmed and Concerned are the most motivated to address climate change but don’t necessarily know what actions to take. We needed to help our visitors shift their thinking to a new reality in which they were actively involved in solutions.

We made the decision to profile local changemakers because of an important insight from other social science research: people need to be invited to participate.[5] When people perceive that their peers, neighbors, or community members are actively participating in environmental actions, they are more likely to join in due to their desire to conform and to be part of something positive.[6] Moreover, invitations to participate are more effective when they are tailored to individual interests and values. Highlighting how a specific environmental action aligns with a person’s personal values or goals can increase that individual’s motivation to get involved. By profiling local changemakers, visitors could begin to see their neighbors–and, ultimately, themselves and their collective actions–as part of the solution rather than feeling like passive observers of the mounting problem.

Striking portraits and personal stories in the exhibition highlighted the work individuals across the Adirondacks are already doing to combat climate change to motivate and inspire our visitors (fig. 4). We selected individuals with a variety of backgrounds, interests, and experiences that would allow visitors to relate to and connect with their stories. Alongside each portrait, we featured the individual’s name and a few short descriptors selected by that person (e.g., “Mom, Winter Lover, and Swimming Junkie;” “Jedi Warrior, Troublemaker, Runner;” and “Pro-Bell Pepper, Anti-Zucchini, 5’10″”) to grab visitors’ attention and help them quickly get to know the changemakers beyond traditional job titles like scientist or farmer. Once we piqued visitors’ interest, they could read more about each person’s work locally and how it connected to the climate movement.

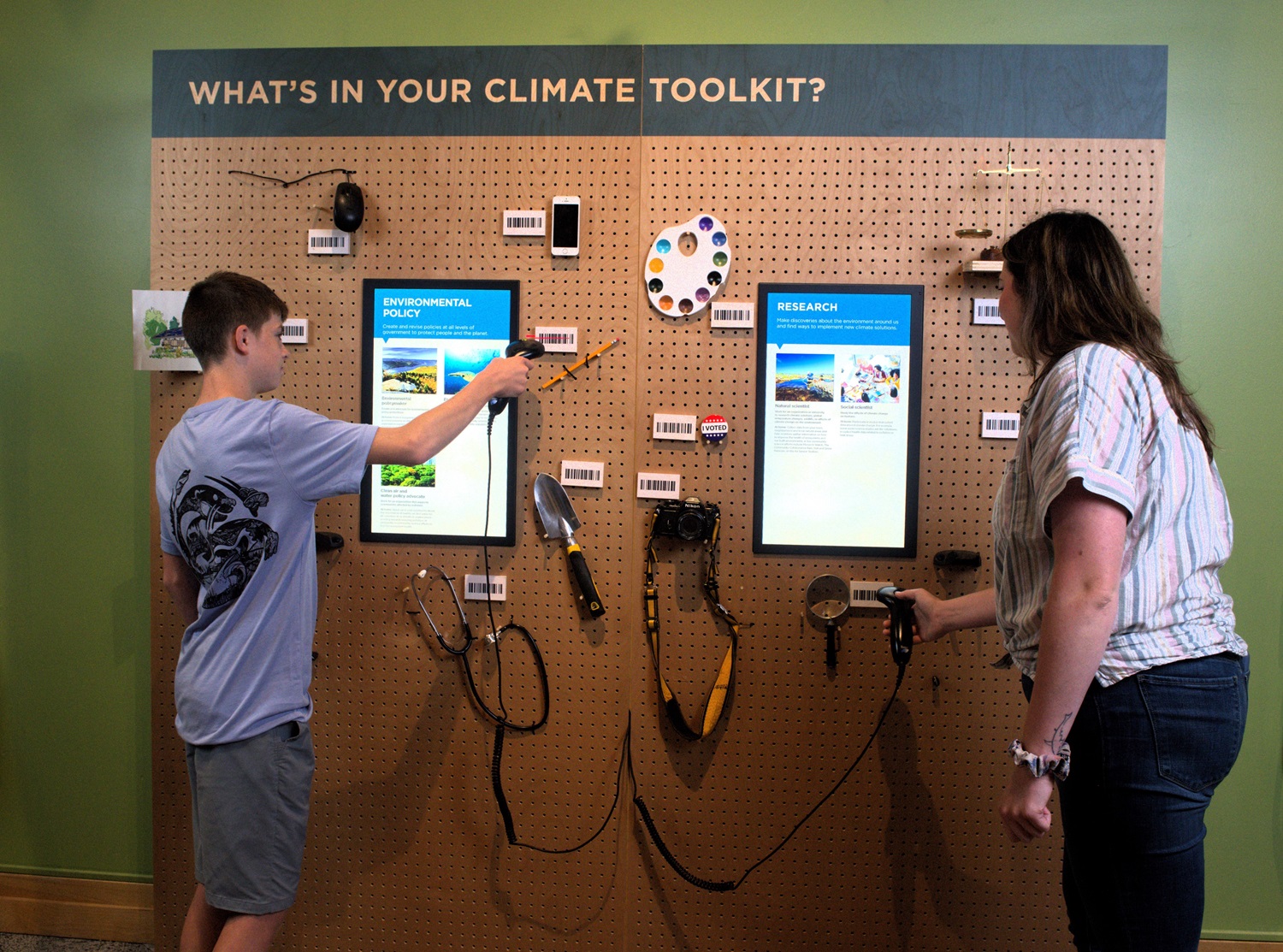

In other parts of the exhibition, we used interactives to communicate the idea that although we all can’t do everything, we can all do something. To make a meaningful difference in the climate crisis, our society needs to shift to new ways of doing things. It can be overwhelming to imagine how it will all get done in time. But when visitors realize each person’s part of the solution is based on skills they already possess, the problem seems more manageable. For example, the Climate Toolkit interactive is designed to help people find connections between their own skills and interests and the climate movement (fig. 5). Using a grocery scanner, visitors can choose a “tool” (such as a paint palette, stethoscope, or magnifying glass) and scan it to reveal different ways that skills or interests related to that tool can be used in the climate movement.

Summative Evaluation Findings and Key Recommendations

Kera Collective, our evaluation partner, conducted a summative evaluation of Climate Solutions to explore visitors’ experiences and meaning-making and, ultimately, to understand whether the exhibition’s key messages and invitation to join the climate movement had been successfully communicated to visitors.[7] The summative evaluation included 31 onsite interviews with a random sample of adult visitors as they exited the exhibition to understand their exhibition experience while it was fresh in their minds. The evaluation also included 16 longitudinal interviews conducted remotely with a separate sample of visitors about two weeks after they had visited to understand the lasting impact of the experience.[8] Participants in the longitudinal interviews were recruited using email addresses collected during ticket sales and screened using an online survey to ensure they had spent at least 10 minutes in the Climate Solutions exhibition during their visit. Participants received a gift card incentive for completing an interview.

Overall, the evaluation found that Climate Solutions was successful in creating a hopeful and engaging exhibition that resonated with its visitors–a significant achievement considering the challenges of positively engaging visitors on such a critical and serious topic. Our approach of minimizing the work of convincing and instead skipping straight to solutions paid off. Below, we share a few recommendations based on key findings from the summative evaluation, which are broadly useful for any museum developing exhibitions (or even programming) about climate action and solutions:[9]

- Focus on solutions: When asked about the main message of the exhibition, three-quarters of exit interviewees noticed the solutions focus and came away from the exhibition recognizing the scope of solutions, big and small, that already exist to address climate change–from alternative energy sources to reducing food waste to choosing more sustainable building materials. Moreover, many longitudinal interviewees recalled concrete examples from the exhibition, suggesting that the exhibition’s main message is clear and continues to resonate beyond the visit (fig. 6). While the approach could have felt overwhelming, highlighting a wide range of solutions at varying scales helped visitors feel like “there’s a million things that you can do” to make a positive difference in the world.

- Weave in personal storytelling and place-based examples: Visitors appreciated that the exhibition featured local people sharing personal stories about locally relevant and “practical” solutions. It brought climate change down to a “personal” and “relatable” level and contributed to the feeling that “just regular human beings like you and me” can make a difference. The mix of practical actions, relatable profiles, and locally grounded examples all contributed to the feeling of hopefulness, likely because it fostered a sense of progress that is often lacking when climate change is framed on a large-scale or global level (fig. 7).

- Include a diversity of voices, perspectives, and interests: Visitors appreciated the inclusion of many different voices and experiences related to climate change. Visitors noticed many different types of diversity represented in the exhibition. They liked the variety of stories featured–both the range of climate work (e.g., the arts, farming, solar energy) and the diversity of backgrounds represented (e.g., young and old, BIPOC individuals, etc.). Seeing a wide range of people featured in the exhibition helped dispel the misconception that the environmental movement is being led primarily by “old white guys”–making the climate movement feel more inviting to “anyone.”

Ultimately, the exhibition made strides in helping visitors envision themselves as part of a new here-and-now reality where they (and their neighbors) are working together in the climate movement.

![Figure 6 shows a quote from a Longitudinal interview, "It's always to distressing to see how bad things have gotten. But it's also uplifting that so many people are trying to find ways to make it better. And that any of us could be a part of the solution. Going back to some of the personal stories [in the exhibition] that were told by some of these individuals with their photos and what they were doing... it just felt like they were speaking to me. I felt a spectrum of emotions actually, from being upset about how bad things have gotten but also seeing their efforts and feeling better that there's still changes to improve what we do so we can take better care of the planet."](https://www.aam-us.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/fig5.jpg?resize=1500%2C672)

![Figure 7 is a quote from an on-site interview, "Honestly, it made me feel more hopeful about [climate change] that we have some solutions in place and that people are taking actions to move in the right direction... this was a very hopeful way to present it. Seeing all the testimonies of the farmers and the different people who are taking action in small steps in their communities, and really putting that into practice. Also, what was really cool is you could relate to each of them. They talked about the different things they were interested in, the things that they did, not only what their work was, but just who they were as a person. That made it very personal."](https://www.aam-us.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/fig6.jpg?resize=1500%2C672)

Final Thoughts

Front-end research has always been extremely helpful in grasping where audiences are in their understanding of a particular topic. The use of the SASSY very early in our exhibition-development process was key to helping us understand our audience and their thinking. Perhaps one of the most important learnings was realizing the eye-opening mismatch between our perceptions of our visitors and their true feelings.

We could have self-censored our approach and framing based on the erroneous fear that our audience was less knowledgeable and less motivated to engage in actions to combat climate change that they really were–perhaps polarized politics had seeped into the walls of our museum making us timid about the topic. However, the results of the SASSY were a game changer. Not only did the results help us define our audience for the exhibition and set a path for our solutions-focused approach, they have also helped our staff feel more comfortable and confident in talking about climate change with visitors in general. This has expanded our museum’s ability to amplify local climate solutions, elevate climate stories from across our region, and engage with our visitors in a more meaningful way.

Our experience makes the case for slowing down and testing your assumptions about your audience when dealing with challenging, complex, and sensitive topics, of which climate change is just one. When you better understand where your visitors are starting from, you are not only better equipped to support them where they need it but also to gently push them beyond where you may have thought you could take them.

[1] “Drawdown: The World’s Leading Resource for Climate Solutions,” Project Drawdown, accessed August 25, 2023, https://drawdown.org/.

[2] “Exhibit: Climate Solutions,” The Wild Center, accessed August 25, 2023, https://wildclimatesolutions.com/exhibit/.

[3] “Six Americas Super Short Survey (SASSY!),” Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, April 20, 2022, https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/visualizations-data/sassy/.

[4] “Global Warming’s Six Americas, December 2022,” Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, March 14, 2023, https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/publications/global-warmings-six-americas-december-2022/.

[5] See, for example, Carl Latkin, Lauren Dayton, Haley Bonneau, Ananya Bhaktaram, Julia Ross, Jessica Pugel, and Megan Weil Latshaw, “Perceived Barriers to Climate Change Activism Behaviors in the United States Among Individuals Highly Concerned about Climate Change,” Journal of Prevention 44 (2023): 389–407, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-022-00704-0; and Matthew Goldberg, Xinran Wang, Jennifer Marlon, Jennifer Carman, Karine Lacroix, John Kotcher, Seth Rosenthal, Edward Maibach, and Anthony Leiserowitz, “Segmenting the climate change Alarmed: Active, Willing, and Inactive,” Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, July 27, 2021, https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/publications/segmenting-the-climate-change-alarmed-active-willing-and-inactive/.

[6] Gregg Sparkman, Lauren Howe, and Greg Walton, “How Social Norms Are Often a Barrier to Addressing Climate Change but Can Be Part of the Solution,” Behavioural Public Policy 5, no. 4 (2021): 528–55, https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2020.42. See also, Ayana Elizabeth Johnson and Katharine K. Wilkinson, ed., All We Can Save: Truth, Courage, and Solutions for the Climate Crisis (New York: One World, 2020).

[7] Kera Collective, “The Wild Center Climate Solutions Exhibition Summative Evaluation,” Informal Science Community: Evaluation Reports, September 30, 2022, https://www.informalscience.org/wild-center-climate-solutions-exhibition-summative-evaluation.

[8] Longitudinal refers to conducting an interview after a period of time has passed, rather than during or immediately following an experience. In this case, interviews were conducted two weeks after the visit.

[9] All quoted words and phrases are taken from interview transcripts from the summative evaluation.