The field of neuroarts is documenting how the arts and aesthetic experiences measurably change the body, brain, and behavior.

This article originally appeared in Museum magazine’s May/June 2024 issue, a benefit of AAM membership.

The mind, once stretched by a new idea, never returns to its original dimensions.”

—Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882)

Ralph Waldo Emerson was more prescient than he could ever have realized. It was not until the 1960s that neuroscientist Marian Diamond discovered that exposure to enriched environments increased brain matter, specifically in the brain’s outer layer, the cerebral cortex. Prior to her landmark research, scientists believed that the brain remained static until it started to decline in older age. Diamond was the first to observe the brain’s neuroplasticity, yet her findings were disputed and rejected for many years. Today she is considered one of the founders of modern neuroscience.

Museums are the ultimate enriched environments, or super-enriched spaces, that are good for body, mind, and soul. Museums are dedicated to arousing our curiosity; engaging us in discovery and learning; and evoking our reflection, wonder, and awe. Artists (and Emerson) have known intuitively what scientists are now proving with rigorous research: aesthetic experiences affect us in extraordinary ways. In short, our brains are wired for art.

Within just the past 25 years, significant advances in technology have allowed us to peer more deeply into that magnificent mechanism that is the brain and better understand what happens when we participate in the arts and aesthetic experiences. The relatively new science of neuroaesthetics studies how the arts and aesthetic experiences measurably change the body, brain, and behavior—and how this knowledge can be translated into specific practices that advance health and wellbeing. We call the field neuroarts.

Four Concepts of the Neuroarts

The science underpinning the neuroarts can be described through four core concepts. The first is neuroplasticity. Each of the 100 billion neurons in the human brain connects to about 10,000 other neurons, and the act of connecting is called a synapse. Neurons need to communicate with one another in order to survive, and novel experiences, such as visiting a museum, create new memories and new connections in our brains. The brain filters the continuous stream of sensory stimuli it receives, retaining the most important ones as memories while discarding the rest.

The second core concept is enriched environments. Scientists who have followed and expanded on Diamond’s research have a better understanding of how enriched environments can positively affect our learning, wellbeing, health, and relationships. We are also beginning to understand how to use the pillars of human flourishing—curiosity, awe, surprise, humor, and novelty—to build new neuropathways. Buildings that incorporate intentional and inspirational architecture, interior spaces, and objects can offer deep emotional and lasting connections among those who live, work, and play in them. On the flip side, impoverished environments can have a slow and corrosive effect on health and wellbeing.

The third concept of the neuroarts is the “aesthetic triad.” Developed by University of Pennsylvania professor Anjan Chatterjee and his colleagues, the triad is a theoretical model that explains how our sensorimotor systems, our reward system, and our cognitive knowledge and meaning-making combine to form a unique aesthetic moment. The model is visualized as a Venn diagram with three circles overlapping in the center, which is the aesthetic experience. The experience is unique to each of us, considering our biology and individual circumstances. The triad helps explain why we might prefer Renaissance art over modern art or enjoy playing a musical instrument more than painting.

The final core concept is the default mode network (DMN), now thought to be the home for the neurological basis of the self. Situated in several parts of the brain, the DMN collectively is the place where our minds wander, wonder, and daydream. The DMN is the neural container that holds our preferences, and it influences how we will react to a piece of art, music, spaces, people, and other experiences.

Perhaps the best news from our research in the neuroarts is that the benefits of aesthetic experiences do not depend on skill. From the very young to the very old, experiencing art in any of its many forms yields multiple positive outcomes, and talent is not a requirement. This is true especially for people who are recovering from a stroke or traumatic brain injury, have mental health concerns including PTSD, or are living in extremely high-stress communities or situations. Longitudinal studies in the United Kingdom suggest that engaging in an arts activity just once a month can lengthen the lifespan by 10 years.

NeuroArts Blueprint

In 2021, the International Arts + Mind Lab at Johns Hopkins University and the Health, Medicine & Society Program at the Aspen Institute partnered to determine a definitive path forward for the neuroarts field. They created and launched the NeuroArts Blueprint, a five-year global initiative to ensure that the arts and the use of the arts—in all of its many forms—become part of mainstream public health and medicine. The blueprint is based on five core recommendations:

- Strengthen the research foundation of neuroarts.

- Honor and support the many arts practices that promote health and wellbeing.

- Expand and enrich educational and career pathways.

- Advocate for sustainable funding and promote effective policy.

- Build capacity, leadership, and communications strategies.

Museums create profound and memorable aesthetic experiences for their audiences through the collections and stories shared, making them important partners within the NeuroArts Blueprint. The blueprint is developing a global resources center where museums can both share their work and learn from other organizations. The resource center will include a calendar of events along with funding opportunities, toolkits, professional development, and research.

The blueprint has also launched a community neuroarts coalition initiative where museums, libraries, community and cultural organizations, academic partners, philanthropy, and municipal partners come together at a hyper-local level to address community needs through the lens of the arts and aesthetic experiences.

We are beginning to understand how culture and community through art making and aesthetic experiences are increasing our capacity for imagination and creative thinking. As museums reflect on their evolving role in communities, they might consider expanding their missions to include improving the health and wellbeing of all populations.

For AAM resources on health and wellbeing visit bit.ly/health-wellbeing-topic and bit.ly/wellness-compendium.

Do you have health and wellbeing programs at your museum? Let us know by providing brief details at

bit.ly/wellness-submissions.

SIDEBAR

Enhancing Museum Aesthetic Experiences

Museums already add to the wellbeing of communities they serve. Here are some ways they can be more intentional about it.

Offer immersive and interactive experiences. Research showed that working on an art project for 45 minutes—regardless of skill—can reduce stress by 25 percent. Additionally, people who engaged in the arts were found to have lower mental distress, better mental functioning, and improved quality of life. Consider creating dedicated spaces for visitors to doodle and draw or express their thoughts in writing. Museum staff will benefit from opportunities to participate in these immersive and interactive experiences as well.

Bring more color and nature into the museum. Our eyes can detect more than 10 million hues, and experiencing different colors can change our blood pressure, heart rate, and respiration. Similarly, viewing nature has the capacity to reduce stress and anxiety. Think of ways to bring the outside in and create colorful, nature-inspired spaces.

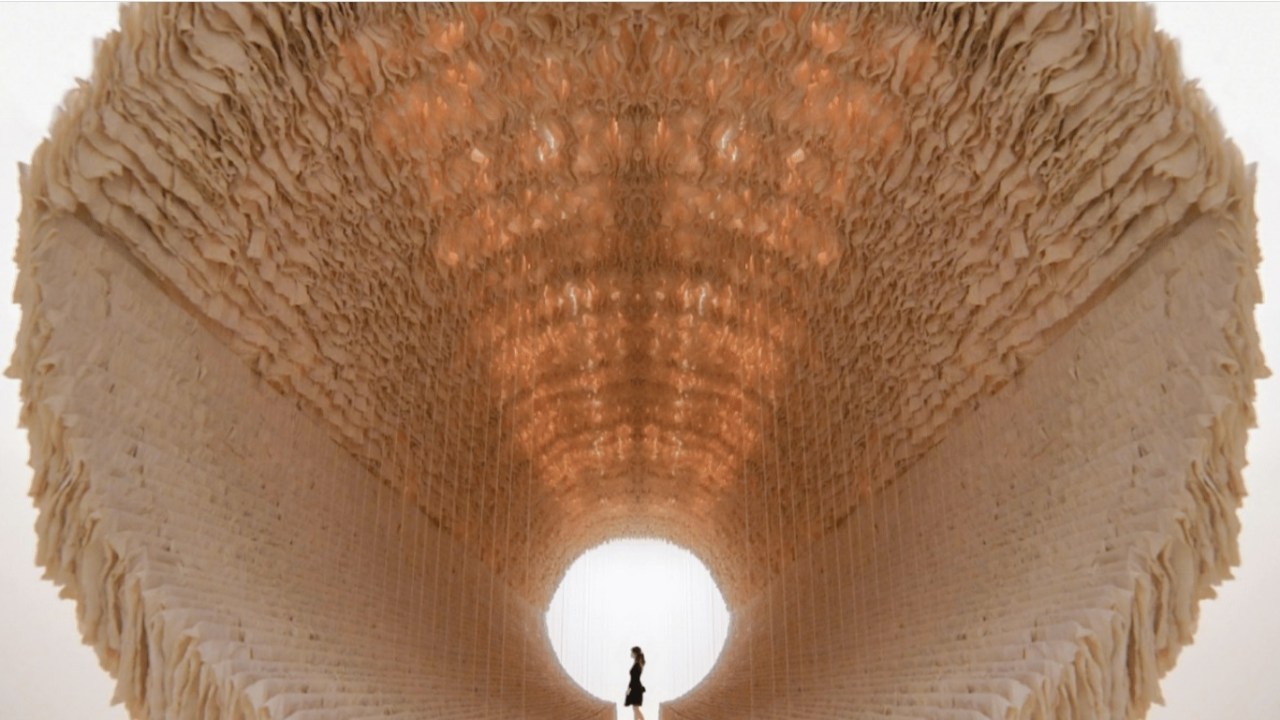

Think curves rather than corners. Scientists theorize that our brains evolved to recognize—and prefer—curves and rounded objects rather than straight lines and sharp corners. Increasingly, architects are integrating more natural curves into building design and renovation. How could this be incorporated into exhibition design?

Offer traveling exhibits to under-resourced communities. Consider a temporary exhibition in an empty storefront or marketplace stall in a community where residents may not have the opportunity to visit the local museums.

Reach out to health care professionals. An increasing number of health care providers are prescribing arts and aesthetic experiences for their patients. Invite health care professionals to your museum to learn more about how museums can address cognitive issues, isolation, and loneliness and build community.

Resources

Susan Magsamen and Ivy Ross, Your Brain on Art

yourbrainonart.com

NeuroArts Blueprint

neuroartsblueprint.org

International Arts + Mind Lab, The Center for Applied Neuroarts

artsandmindlab.org

Arts on Prescription: A Field Guide for US Communities

arts.ufl.edu/sites/creating-healthy-communities/resources/

arts-on-prescription-a-field-guide-for-us-communities/