A primer for cultivating more inclusive attitudes among the public.

This article originally appeared in Museum magazine’s July/August 2024 issue, a benefit of AAM membership.

The following is an excerpt from Audiences and Inclusion: A Primer for Cultivating More Inclusive Attitudes Among the Public.

American attitudes toward inclusion are divided, complicated, and messy. They are also tied to emotions, values, and identity. National research indicates that there is a steep road ahead in building a truly just and equitable society. According to Pew Research Center and Public Religion Research Institute, 39 percent of US adults say there is discrimination against men in our society, and just 34 percent of registered voters in the US think white people benefit “a great deal” from advantages in society that Black people do not have. Additionally, their research shows 44 percent of white Americans think discrimination against white people has become as big a problem as discrimination against Black Americans and other minorities, and 49 percent of Americans describe immigrants as a “burden to local communities.”

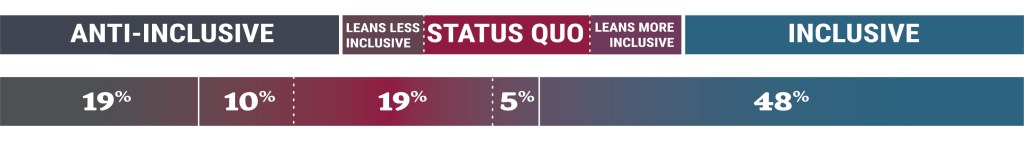

What about museum-goers? How do they feel about inclusion? Our research (see graphic below) indicates less than half of museum-goers are proactively inclusive, so for us to be most effective in sharing inclusive content, we have to grapple with the fact that the majority of our audiences are not seeking inclusive content. The good news is that museum-goers are about twice as likely to want inclusive content as they are to reject it, and research consistently shows that the broader population is more likely than museum-goers to want museums to be inclusive. Additionally, inclusive content in museums can have major societal impact by helping our existing audiences become more inclusive and welcoming to new people in museum spaces.

Understanding Visitors

To understand how to expand inclusive attitudes, we have to examine our visitors more closely. Inclusive attitudes can vary widely, so it’s helpful to back up and examine what influences us in the first place. Factors like one’s upbringing, race, parental attitudes, and so much more help us each develop our unique values, attitudes, beliefs, and worldviews. In the aggregate, that means our audiences comprise a spectrum of worldviews, and while individuals have their own unique blends, there are key traits that tend to cluster together, forming what we’ll call “traditional” and “neoteric” segments that reflect society’s polarization. There is also a “middle,” but most people tend to lean one way or the other.

The “traditional” segment is more likely to be:

- anti-inclusive

- politically/socially conversative

- somewhat less engaged with museums and culture

- generally less engaged with their community and the broader world

of the belief that museums should be “neutral” and not take positions

- taking a “traditional” and often taking a celebratory approach to history and their own culture

- taking pride in the past and their own cultural heritage

- somewhat less curious

- demographically older, more men, and have less educational attainment

The “neoteric” segment is more likely to be:

- inclusive (though some may be fine with the status quo)

- politically/socially liberal

- somewhat more engaged with museums and culture

- generally more engaged with their community and the broader world

of the belief that museums can take an evidence-backed position

- taking an additive approach to history and culture

- curious about other cultures and worldviews, and more curious generally

- demographically younger, more women, and have more educational attainment

It is tempting to use these trait clusters, especially the demographic ones, to make assumptions about individual visitors. Don’t do it! Just because certain traits clustered together doesn’t mean they apply to the individual standing in front of you. In other words, an older white man can certainly be “neoteric” in his worldview, and, similarly, a young woman of color can be “traditional.” You have to get to know that visitor, and their worldviews, to begin to understand where they may fall on the spectrum.

But what about the status quo group—that messy middle group that isn’t seeking inclusive content but is not rejecting it either? This group represents our biggest opportunity! Since they are not rejecting inclusive content, we can help them become more inclusive in their own attitudes if we move at, as Adrienne Maree Brown describes, the “speed of trust.”

Everyone wants their identity to be recognized and valued in cultural spaces, but for those with a more “traditional” worldview, inclusive content can feel like a threat to their understanding of the world, their beliefs and customs, and even their identity. That results in a potential emotional response of fear that can be strong, palpable, and defensive.

So how do we mainstream inclusive content when our audiences are so divided and when emotional responses are so strong? That’s tricky, because while museums provide informal learning opportunities, expanding knowledge through evidence doesn’t always work, especially when fear drives a defensive response in a sizable segment of our audience. We need to understand how values, attitudes, beliefs, and emotions affect how individuals approach information in the first place.

As human beings, we practice what is known as intuitive epistemology all the time. That is, individual values and life experiences deeply affect how people process and establish facts. This also deeply affects the questions we ask about the past, science, social issues, and art, and thus the answers we find can vary based on our worldviews. When we ask different questions of museum content, we use that content to find answers that validate our individual worldviews and avoid content that creates dissonance. This is how two people can approach a single topic, such as climate change or the Civil War, and come to radically different conclusions. This is simply human nature and why “dueling facts” divide us and feed a culture of alternative facts, polarization, and cancellation. In fact, one thing most of us seem to agree on is that we can’t even agree on facts.

It is practically impossible to use evidence to change minds in a world of dueling facts. Instead, we need to consider how to help visitors change the questions they are asking as they approach content. By asking visitors new questions to consider, new information feels less threatening. Additionally, asking visitors to consider new, dialogic questions also makes them feel valued, especially more “traditional” visitors. Why? Because it fits into a desired pattern of museum engagement, which is to be presented with facts and given the opportunity to make up one’s own mind. So, your job then is to use questions to help visitors consider ideas and facts that they may not otherwise think of and crack open those worldviews, whether a tiny amount or significantly.

Developing an Inclusive Practice

Of course, there is more to inclusive practice than asking good questions. True inclusive practice and expanding the number of people who have inclusive attitudes begins with us. To be effective in our work, we need to also deploy radical curiosity and courageous empathy in our practice. By striving to understand different worldviews, what shaped them, and anticipating how those with differing worldviews respond to the content we share, we can create respectful environments where visitors are encouraged to ask new questions that just might broaden their worldviews in ways that matter. The 10-step primer below can help you in your inclusive practice.

Step 1: Acknowledge your bias from the beginning and then encourage your visitors to do likewise. Create a plan to address your biases (e.g., advisors, team approach, etc.), and be upfront with your audiences about how you strove to mitigate them. We all have biases, and acknowledging them from the beginning engenders trust. Additionally, gently asking your audience to consider how their own values and attitudes influence how they assess information can put them into a mindset that is more open to nuance.

Step 2: Reinforce their aspirational identity as curious, open-minded, and/or well-rounded individuals. Doing so can make it more likely that they will strive to achieve those aspirations, and this basic human psychology can be deployed to achieve pro-social outcomes. This aspirational reinforcement makes it more likely they will live up to those descriptors and consider new content or perspectives.

Step 3: Spark hedonic and eudaemonic curiosity (for more information on these types of curiosity, read the full primer at aam-us.org/audiences). Since we just validated aspirational identity, now is the time to create information gaps that stretch visitors just a bit. This stretching happens in two ways: introducing ideas just outside of visitors’ normal worldviews and helping visitors be more comfortable with uncertainty or even ambiguity. Both help them approach a complicated world more openly.

Step 4: Engage in dialogic questions. Present audiences with questions that their worldviews may not have considered, and practice courageous empathy by being open to their answers. Because of the intuitive epistemology we all practice, reframing questions is crucial. Now that visitors are in a more open mindset, and are seeing information gaps, help them formulate new questions that continue to help them stretch. “Consider this” is a great way to introduce a new question in a nonthreatening way. Mutual respect is important here. Sometimes, the answer visitors give still may not be inclusive. If we disparage those answers, we lose our credibility and our opportunity to try again.

Step 5: Give them all the facts. That includes multiple perspectives and telling the truth, even when it changes our understanding of the past, different cultures, or others. More “traditional” audiences often say, “Just give me the facts, and I’ll make up my own mind.” Thus, it is entirely appropriate to do just that, and give them all the facts. The trick is that sometimes the facts you share may not be what they expected. Hopefully, their curiosity has been sparked enough to consider those new facts thoughtfully and respectfully.

Step 6: Show your work. Trust cuts both ways, so you need to share your process and sources, and identify your advisors. In a time of “alternative facts,” showing your work is more important than ever. This can be as basic as footnotes in an exhibition or tour guides noting that a list of sources can be found on your website. It doesn’t matter if visitors actually check your references because the fact that you are providing that evidence signals credibility.

Step 7: Mainstream inclusive content, and never apologize for being inclusive. When museums, as highly trusted community institutions, mainstream inclusive content, it helps community belief systems shift to embrace it as well. And when that happens, visitors better contextualize detractors as outliers and become more likely to choose acceptance, tolerance, and understanding.

Step 8: Pace your work at the “speed of trust.” Some of the content you share may be difficult for some visitors, especially if it represents a change from what they thought they understood. Do not make them feel dumb and do not preach. It is so hard to slow down our work to bring others along with us, yet that is crucial if we are going to expand the number of people who want inclusion. So, think through how you are presenting content, and ensure it allows for empathy to grow.

Step 9: Be a forum for civil discourse. Most museum-goers are not asking museums to be places of civil discourse, but when museums do it effectively, it can be transformative. This is a case of “do it even when we are not being asked to.”

Step 10: Accept that, despite your best efforts, you will not be 100 percent successful. Have the confidence to know you’re doing your best and planning the most effective path. This makes it easier to keep your focus on your goal and not let detractors stop your work.

Inclusive practice takes work, but with radical curiosity, courageous empathy, and thoughtful engagement, museums can make a tremendous difference in promoting a more equitable and just world.