There are evidence-based strategies museums can employ to become sites of depolarization and civil discourse.

This article originally appeared in Museum magazine’s July/August 2024 issue, a benefit of AAM membership.

In our current divisive political landscape, museums are in a unique position to mitigate polarization. As individuals increasingly retreat into echo chambers and ideologically homogeneous networks, opportunities to engage with those with different views are dwindling. This lack of interaction breeds misperceptions and animosity, further exacerbating the fractures within our society. As one of the few institutions still trusted by the American public, museums can break these silos and bring people together to engage in healthy civil discourse.

Navigating this terrain may seem daunting, particularly amid the headlines on the latest culture wars and contentious school board meetings. Yet decades of research in social psychology, as well as insights from organizations like my organization More in Common, point to strategies that museum professionals can employ to cultivate spaces conducive to civil discourse and constructive dialogue—both internally between staff and board and externally among visitors from all walks of life.

Values, Not Partisan Affiliation

The first rule of engagement for civil discourse is to see people beyond partisan and demographic labels, understanding that we are driven by distinctive values and core beliefs. Core beliefs are psychological attributes, the “hidden architecture” that influences our worldviews and behaviors. One dimension of core beliefs is moral values. The Moral Foundations Theory, developed by social psychologists Jonathan Haidt and Jesse Graham, suggests that there are five or more “moral foundations” that underlie people’s moral judgments:

Care: protecting the vulnerable and helping those in need

Fairness: relating to proportionality, equality, reciprocity, and rendering justice according to shared rules

Authority: respect for traditions and submitting to legitimate authority

Purity: abhorrence for things that evoke disgust and prioritizing the virtues of self-discipline

Loyalty: standing with one’s group, family, or nation

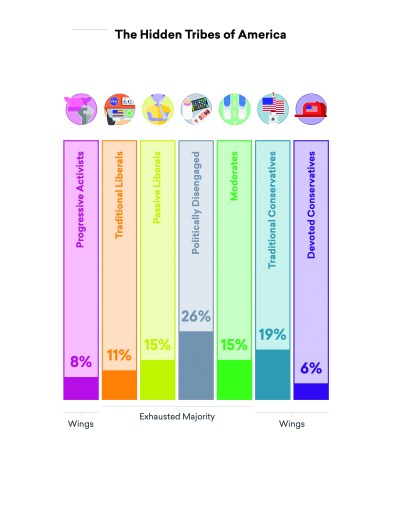

In More in Common’s landmark study The Hidden Tribes of America, we find that rather than being divided into two political camps, American society today consists of seven distinctive groups—Progressive Activists, Traditional Liberals, Passive Liberals, Politically Disengaged, Moderates, Traditional Conservatives, and Devoted Conservatives—that form based on their core beliefs and social-psychological profiles, including moral foundations.

Similar to how individuals have different food preferences shaped by variations in taste buds, eating habits, and the environment they live in, people also prioritize different moral foundations based on their personality, upbringing, life experiences, and cultural influences. For example, individuals from the Progressive Activists tribe highly value care and fairness, while Devoted Conservatives emphasize authority, loyalty, and purity.

In our study, we found that how people prioritized each moral foundation often predicted their views on social and political issues:

Care: correlates with support for policies and causes that protect or elevate historically marginalized groups

Fairness: correlates with support for equal and just treatment under shared rules, such as closing the gender pay gap

Authority: correlates with support for policies that enforce law and order

Purity: correlates with views on sexuality, religion, and spirituality

Loyalty: correlates with support for behaviors that demonstrate loyalty and obligation toward one’s community or country

These findings have two important implications for museum professionals trying to create spaces for civil dialogue. Firstly, disagreements and conflicts are often not driven by political affiliation but differences in the values we prioritize. It is crucial to encourage staff and visitors alike to avoid framing different opinions on social issues solely through the lens of partisan affiliation and recognize the deeper values that animate people’s worldviews.

Secondly, by understanding the moral bedrocks that individuals hold, museum professionals can avoid language that violates certain moral values and triggers defensive reactions. For example, for staff, board members, or visitors who prioritize loyalty, it may be useful to reframe language that could be seen as disdainful of their communities or countries.

In addition, new data from the Civic Language Perceptions Project by the Philanthropy for Active Civic Engagement further explores which terms Americans like and don’t like, as well as which terms bring us together, drive us apart, and motivate us to act. For example, the study finds that words such as “unity” and “belonging” are received positively, while “social justice” and “equity” are more polarizing for particular audiences. It is therefore imperative for museum professionals to discern and curate language that speaks to their audiences’ core values.

Correcting the Perception Gap

Research by More in Common finds that Americans often have exaggerated, incorrect assumptions about the views of their political outgroups, or those they perceive to be the “other side.” We call this phenomenon perception gap—the difference between what we imagine a group believes versus what that group actually believes. For example, in More in Common’s study “Defusing the History Wars,” we find that 95 percent of Democrats believe that “throughout our history, Americans have made incredible achievements and ugly errors.” Yet Republicans think only 55 percent of Democrats agree with that statement. Similarly, 93 percent of Republicans say that “Americans have a responsibility to learn from our past and fix our mistakes.” Yet Democrats think only 35 percent of Republicans agree.

Perception gaps work in an almost self-reinforcing cycle: they obscure commonalities and make us believe that our differences are so vast that productive conversations are impossible, thereby reducing interest in dialogue and further perpetuating our misperceptions of each other. Thus, museum professionals who focus on correcting perception gaps can, as a result, also address incorrect assumptions, foster curiosity, and diffuse tension ahead of difficult conversations. There are several ways that a perception gap framework can be incorporated in museum practice:

- Encourage participants to reflect on their own misperceptions.

- Contrast participants’ perceptions with reality, exemplified by statistics and personal stories.

- Depict individuals who are similar to the participants changing their minds about a topic, issue, or an opposing group. (Our research shows that Democrats are more likely to change their minds about Republicans if they watch video testimonials of fellow Democrats changing their opinions about Republicans, and vice versa.)

As divisions grow leading up to the 2024 election, museums have a critical opportunity to cultivate engagement across lines of differences. Museums can not only be public arenas that foster healthy civil dialogue but also shape how individuals engage with one another in our polarized political climate. The positive impact of this work will extend beyond local communities, offering a blueprint for other institutions seeking to build social cohesion.

Sidebar

Tips for Dismantling Silos

Following are practices grounded in social psychology that museum professionals can use to bridge divides.

Encourage perspective-giving and perspective-taking. Research shows that sharing personal perspectives and experiences (perspective-giving) as well as accurately summarizing and reflecting on the stories shared by others (perspective-taking) utilizes the power of being heard to change attitudes toward opposing groups.

Focus on personal experiences. Include opportunities for participants to share personal stories related to political issues. Research finds that personal experiences bridge moral and political divides and lower intolerance better than facts.

Emphasize shared identities. Highlight local identity, American identity, and common interests to foster connection despite political differences.

Build dialogue skills. Teach participants to adopt communication strategies that promote curiosity and respect for differing viewpoints, such as active listening and showing appreciation for input.

Employ moderation and facilitation. Assign a neutral moderator to guide conversations and shift discussion goals away from persuasion and toward understanding. Nonprofit organizations seeking to bridge differences, such as the Listen First Project and Braver Angels, have developed facilitation advice that museum professionals could use.

Resources

More in Common US

moreincommon.com/us

More in Common, The Hidden Tribes of America, October 2018

hiddentribes.us

Philanthropy for Active Engagement, Civic Language Perceptions Project 2024

pacefunders.org/Language/

Rachel Hartman, et al., “Interventions to Reduce Partisan Animosity,” PsyArXiv, 2022

doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/ha2tf

Listen First Project

listenfirstproject.org/tips