This is an excerpt from TrendsWatch: Museums as Community Infrastructure. The full report is available as a free PDF download.

“What mental health needs is more sunlight, more candor, and more unashamed conversation.”

The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals identify “good health and well-being” as critical elements in creating a peaceful and prosperous future. Within that broad mandate, the need to foster mental health is particularly acute. The stigma attached to mental illness inflicts additional damage through bias and exclusion, and if people do seek help, they may face financial, geographic, or social barriers to accessing care. COVID-19 may amplify this challenge in the coming decades, with long-term impacts including increased rates of depression, anxiety, and PTSD. A deep body of research has already documented the role museums can play in a resilient and equitable infrastructure of health writ large. The stress test of the COVID-19 pandemic showed that museums can be essential partners in a network of support for mental health as well.

The Challenge

In Western society, the theory and practice of mental health has been shaped by history, philosophy, and traditions that view the mind and body as separate entities. Only recently have we begun to recognize the duality of body and mind as false, and to acknowledge that people experiencing mental illnesses should receive the same respect, compassion, and access to care as people coping with physical challenges.

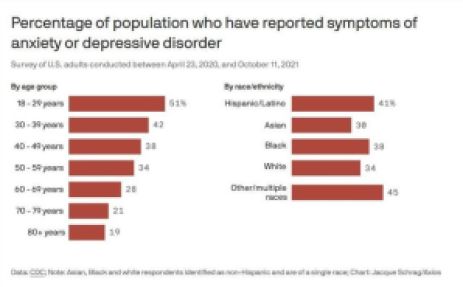

This welcome step toward a rational and caring approach to mental illness comes none too soon. Mental health has been declining in the US since the early twentieth century. Some research suggests one culprit is a cultural shift from intrinsic to extrinsic goals. Other contributing factors include the cumulative effects of racism and discrimination, the rising number of people living alone, and (especially for teens) the dark side of social media, including bullying and body-shaming. Whatever the cause, by 2018, one in five Americans were experiencing challenges to their mental health, and one in twenty faced serious mental illness.

Then came the additional stress, isolation, and fear induced by the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2021, one in every three Americans reported they were suffering from depression, and anxiety and depression severity scores were one and a half to two times higher than they were in 2019. The pandemic’s effects on mental health were particularly severe for people disadvantaged by or excluded from existing networks of support, including women; people who are unmarried; low-income households; children age eleven to seventeen; LGBTQ+ youth; people who identify as Black, Native American, and Asian or Pacific Islander; and people already experiencing mental illness. Medical historians tracking mental health in the wake of other large-scale disasters, including the Chernobyl nuclear accident in Ukraine (1986), the SARS pandemic (2003), and Hurricane Katrina (2005) have found long-term increases in the rates of post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and other mental health problems. The COVID-19 pandemic will likely have a similar long-term impact on mental health. This damage to individuals translates into damage for critical systems as well. The past two years have been particularly hard on front-line workers, with one result being that many essential personnel, including health care workers and teachers, may leave their professions, further weakening our ability to support community needs.

Over the course of the pandemic, as museums were forced to close their doors to the public, many museum workers experienced layoffs, furloughs, and financial stress. Others scrambled to move their work online or fill different roles. Reopening brought its own challenges, including increased workloads and the stress of enforcing safety policies with occasionally hostile or combative patrons. The results of a survey conducted by the Alliance in March 2021 reflected the toll this has taken on people working in the museum sector, with respondents rating the pandemic’s effect on their mental health and well-being at an average of 6.6 on a scale of zero to ten (ten being the worst). Fifty-seven percent of respondents were worried about burnout, and, perhaps in consequence, fewer than half were confident they would be working in the sector in three years.

The Response

In Society

Pre-pandemic, America was making slow but measurable progress in improving attitudes towards and support for people experiencing mental illness. Many businesses are making voluntary improvements to policies, procedures, and benefits, for example, by offering mental health days or explicitly defining “sick leave” to include time taken to tend to mental health. Increasingly, employees are encouraged or required to use all their vacation time. And human resources staff have learned that it isn’t enough to simply offer mental health support through an employee assistance program; it’s critical to actively cultivate the use of these services by, for example, educating staff on the benefits, simplifying the enrollment process, and providing assurance that personal information is kept private.

We are making progress at the federal level as well. The Mental Health Parity Act of 1996 and the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 required large-group employer insurance plans to cover mental health services at the same level as medical and surgical interventions. Still, many people fell through the holes of existing safety nets. When the Affordable Care Act (ACA) passed in 2010, more than forty-eight million people in the US were uninsured, and many individual and small-group plans did not cover mental health treatment at all. ACA has expanded coverage and access to mental health care and seems to be improving outcomes.

But ACA cannot address some fundamental barriers to mental health treatment, including the stigma attached to mental illness and lack of accessible treatment in some communities. Paradoxically, by making things worse, the COVID-19 pandemic may have sparked progress on those fronts, in particular by accelerating the adoption of telemedicine by practitioners and the public. Between January 2020 and February 2021, mental health televisits increased by 6,500 percent. (That is not a typo.) In addition to connecting to a medical practitioner for a traditional visit over the internet, people in need of counseling can now choose from a burgeoning number of mental health apps to access therapy and cope with stress, anxiety, addiction, eating disorders, or obsessive-compulsive disorder. Early assessment suggests these digital interventions can be effective and reach people without access to traditional care.

The pandemic may provoke a profound cultural shift as well. The past two years have brought conversations about mental illness out into the open in daily conversation, the press, and social media, as people struggled with their own mental health or to support friends and family facing similar challenges. It is possible that this mass shared experience will have a long-term effect for the better, helping reduce the shame, ostracism, discrimination, and marginalization attached to mental illness. Our national challenge is to build on these advances, making permanent changes that support remote access to appropriate care, elevating the importance of mental health, and destigmatizing mental illness.

In Museums

A large body of research documents that engaging with art (through viewing, making, or museum visits) has tangible psychological benefits, reducing symptoms of anxiety and depression as well as reducing social isolation and loneliness. Building on this work, any museum can find ways to explore and illuminate the experience of mental health in ways consonant with their missions.

Science museums often tackle the topic head-on, as the Museum of Science, Boston, and the Science Museum of Minnesota did in recent major exhibitions. Historic houses and sites, of which there are an estimated eighteen thousand in the US, also have a compelling opportunity to address the topic, because many of the people challenges. (To name just a few from what would be a very long list: Abraham and Mary Lincoln, Nikola Tesla, Eugene O’Neill, and Winston Churchill). This provides an opportunity to surface and normalize the experience of mental illness, even though that conversation may not be the content visitors expect. Staff may need to navigate public expectations as they reframe how a site interprets the history and current impact of mental health.

Any museum can use the human element behind its topic—art, science, music, literature, natural history, or other—to address mental health in some part of its interpretation. Simply acknowledging the fact of mental illness as an important component in the lives of notable people can help to destigmatize the topic and recognize a range of conditions as part of the human experience.

Sometimes museums can also help with struggles that are not just individual, but traumas shared by a community. Many museums have stepped forward to take on this role in the wake of disasters, for example, by fielding teams for rapid response collecting to help the community remember and process what has happened. Some museums are specifically created to help communities memorialize, contextualize, and process the impact of tragic events. These museums often take a trauma-informed approach to their exhibit design and offer programming to support the healing of their communities.

While museums contribute unique strengths to the infrastructure of mental health, they rarely have staff who are experts in dealing with mental illness or in communicating around a topic that can be very sensitive and upsetting. For this reason, museums that address mental health skillfully and powerfully often draw on the expertise of hospitals, university research departments, and social service organizations.

During the pandemic, museums had to look to the safety and wellbeing of their own staffs to create a stable base from which to help their communities. The same AAM research referenced above that explored the damage inflicted by the pandemic on people working in the museum sector also documented what museums were doing to care for their employees. Some of the actions most appreciated by staff included providing clear communications about information and decisions, offering a flexible work schedule, and including staff in decision-making. These lessons can help museums lay the foundation for a healthy work culture in post-pandemic times as well.

During the COVID crisis, museums also looked beyond their walls to support the mental health of their communities in many creative and generous ways. Some created outdoor art installations to boost the spirits of people in nursing homes and hospitals. Others provided online art therapy programs or used their collections and connections to offer mindfulness and meditation experiences online or via podcasts. The success of these programs may ensure they continue to be offered even as the pandemic fades.

Museum Examples

Helping Communities Process Shared Trauma

After the Champlain Towers collapse in 2021, HistoryMiami staff gathered and preserved hundreds of letters, artworks, and personal items placed by friends and families of victims on an impromptu “Wall of Hope” near the site of the disaster. The Orange County Regional History Center (OCRHC) filled a similar role after the Pulse Nightclub mass murders in 2016, creating the One Orlando Collection from thousands of objects left at public memorials or donated to the museum. The Oklahoma City National Memorial Museum and the 9/11 Memorial and Museum are both dedicated to the long-term work of helping their communities memorialize and process the impact of local tragedies.

Creating Networks of Collaboration

The National Museum of Mental Health project is a “museum without walls” that works with artists, curators, mental health professionals, and people with lived experience of mental illness to create touring exhibits, as well as collaborating with community, local, and national not-for-profit, for-profit, governmental, and educational entities interested in creating positive mental health outcomes.

Making Art Therapy Accessible Online

During COVID lockdowns in Ontario, the Art Gallery of Windsor partnered with the local branch of the Canadian Mental Health Association to offer online art therapy programs to support mental health and wellbeing. The National Museum of Qatar worked with art psychotherapists, psychiatrists, and physicians to create and pilot a telehealth art therapy program for children to counteract the effects of social distancing and isolation. The Tampa Museum of Art provides both virtual and in-person sessions for Connections, its free mental healthcare community art engagement program.

Partnering with Community Health Organizations

In 2015, the Tate Modern collaborated with a range of mental health organizations, including arts networks, art studios, and community service providers, to produce workshops and installations celebrating positive mental health to mark World Mental Health Day. In 2017, Utica Children’s Museum merged with the ICAN Family Resource Center, a nonprofit dedicated to providing “individualized and non-traditional services and care to the highest risk individuals and families with social, emotional, mental health and behavioral challenges.” ICAN is in the process of building a new facility that will house the museum together with family services, using trauma-informed approaches to design exhibits and programs to create a welcoming space for all children. Some of the staff at the newly reopened museum will have degrees in social work and will draw on ICAN’s clinicians and social workers for additional training.

Addressing Mental Illness Through the Lens of Mission

In 2017, the National Building Museum opened Architecture of an Asylum, an exhibition exploring the evolution of the theory and practice of caring for the mentally ill through an examination of the history of St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Washington, DC. The exhibit traced how reformers such as Dorothea Dix helped foster the development of a more humane and compassionate approach towards caring for people with mental illness. In 2020, Kew Palace opened George III: The Mind Behind the Myth, an exhibit that used historic and contemporary displays to challenge contemporary attitudes towards mental ill health. Members of the public contributed objects and recorded videos documenting their own personal mental health stories. Working with the Campaign Against Living Miserably (CALM), a suicide prevention charity, Kew staff provided items, including beer coasters and postcards, designed to support public conversation, and trained staff on how to talk about mental health and suicide in a museum setting.

Explore the Future

Signal of Change:

A “signal of change” is a recent news story, report, or event describing a local innovation or disruption that has the potential to grow in scope and scale. Use this signal to catalyze your thinking about how museums might support mental health in the future.

Brussels doctors to prescribe museum visits for Covid stress

The Guardian, September 2, 2021

Doctors in Brussels will be able to prescribe museum visits as part of a three-month trial designed to rebuild mental health amid the COVID pandemic. Patients being treated for stress at Brugmann hospital, one of the largest in the Belgian capital, will be offered free visits to five public museums in the city, covering subjects from fashion to sewage. The results of the pilot will be published next year, with the intention that the initiative can be rolled out further if successful in alleviating symptoms of burnout and other forms of psychiatric distress. The alderman responsible for culture in Brussels said she had been inspired by a scheme in Quebec, Canada, where doctors can prescribe up to fifty museum visits a year to patients. In the Brussels pilot, accompanied visits will be prescribed to individuals and groups of in-patients at Brugmann hospital.

Implications:

Ask yourself, what if there was more of this in the future? What if it became the dominant paradigm? Write and discuss three potential implications of this signal:

- For yourself and your family and friends

- For your museum

- For your community

Critical Questions for Museums

- What groups, on the museum’s staff and in its communities, are at high risk from stress, isolation, and other factors that can damage mental health?

- How can museums combat the stigma, prejudice, and discrimination attached to mental illness?

- How can museums foster mental health among their own staff and volunteers, create a healthy work culture, and support people in managing mental illness for themselves and their families?

- How can museums equip their staffs with the training, tools, and support they need to address the topic of mental health safely and effectively?

- How can museums play a meaningful role in the network of support and services that address mental health in their community?

A Framework for Action

Inward Action

To create a healthy work environment inside the museum, museums may want to:

- Create a work culture that does not stigmatize mental illness. This includes paying attention to the language used in the workplace, training people to recognize and avoid inappropriate or disrespectful terminology.

- Teach managers how to provide appropriate support and assist the people they supervise in accessing help.

- Have leadership set an example by being open and honest about any challenges they themselves face, and by creating a safe space for others to speak up about their needs.

- Use regularly scheduled surveys to gauge levels of stress among staff and detect early warning signs of burnout.

- Offer staff training around mental health, helping everyone to recognize signals of colleagues who may be in distress, offer appropriate non-judgmental support, and help people to access assistance.

- Implement employment practices that foster stability and resilience. Review the security of employment, e.g., the use of short-term contracts or part-time work that does not include benefits, which can add significantly to employee stress and disproportionately impact front-line workers.

Outward Action

To foster mental health, support people experiencing mental illness, and combat stigma, museums may want to:

- Develop relationships with community resources and agencies, such as health and counseling centers, hospitals, and academic research programs, to explore how the museum can learn from and contribute to their work.

- Familiarize themselves with the research on how arts engagement can foster mental health and assess how to integrate such engagement into their exhibits and programming.

- Provide training for staff and volunteers to support their engagement in the topic of mental health, including how to interface with the public around sensitive and potentially triggering issues and how to manage the personal impact of this work.

- Design safe spaces for the public to explore challenging and potentially uncomfortable or disturbing subject matters. This might include warning visitors about content, providing them with choices to engage or not engage, and providing places designed to support reflection and processing of difficult emotions.

- Consider how the museum will continue to support communities and individuals who collaborate with your organization around mental health. Think about what any given project will produce—information, resources, relationships, etc.—that will continue to benefit these groups after an exhibit or program concludes.

Additional Resources

- The Recovery Room, created by Rachel Mackay, Manager of the History Royal Palaces properties within the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, shares resources related to working with staff and the public around mental health. These include Our Stories, Our Visitors, Our Selves: a model for looking after front-facing teams when telling challenging stories, 10 Tools for Supporting Front of House [Staff], and a video on mental health and front-of-house

- The Culture, Health & Wellbeing Alliance, a free membership organization based in the UK, provides information, training, and peer support. Its resources include toolkits, fact sheets, case studies, research, and evaluation.

- Contemporary Collecting: and ethical toolkit for museum practitioners (London Transport Museum, 2020). This toolkit explores some of the ethical judgments that contemporary collectors make and offers case studies, reflection, guides, and further information. One of the chapters addresses the issues inherent in collecting around topics that might prompt or relate to a person’s experience with trauma or distress.

Comments