This is a recorded session from the 2024 AAM Annual Meeting & MuseumExpo. Through a shared purpose to destigmatize addiction disorder and make social change, in the summer of 2023, a museum, an artist educator, and three organizations serving the recovery community collaborated to impact over 700 individuals. Using this partnership as a case study, this session explores the reciprocal benefits and best practices for supporting road-tested, community-based projects when establishing relationships with new museum audiences.

Additional resources:

Destigmatize Addiction Disorder: Fostering Partnerships for Systemic Change slides

Destigmatize Addiction Disorder worksheet

Transcript

Zoe Fiss: My name is Zoe Fiss, I’m the new Director of Youth and Family Programs at the Milwaukee Art Museum and I’m really honored to be here today with Patty Bode to be speaking about a project we did during my time in Sheboygan at the John McGill Cooler Art Center.

So, I’m going to pass it off to Patty to introduce herself and guide you through a starting warm-up exercise.

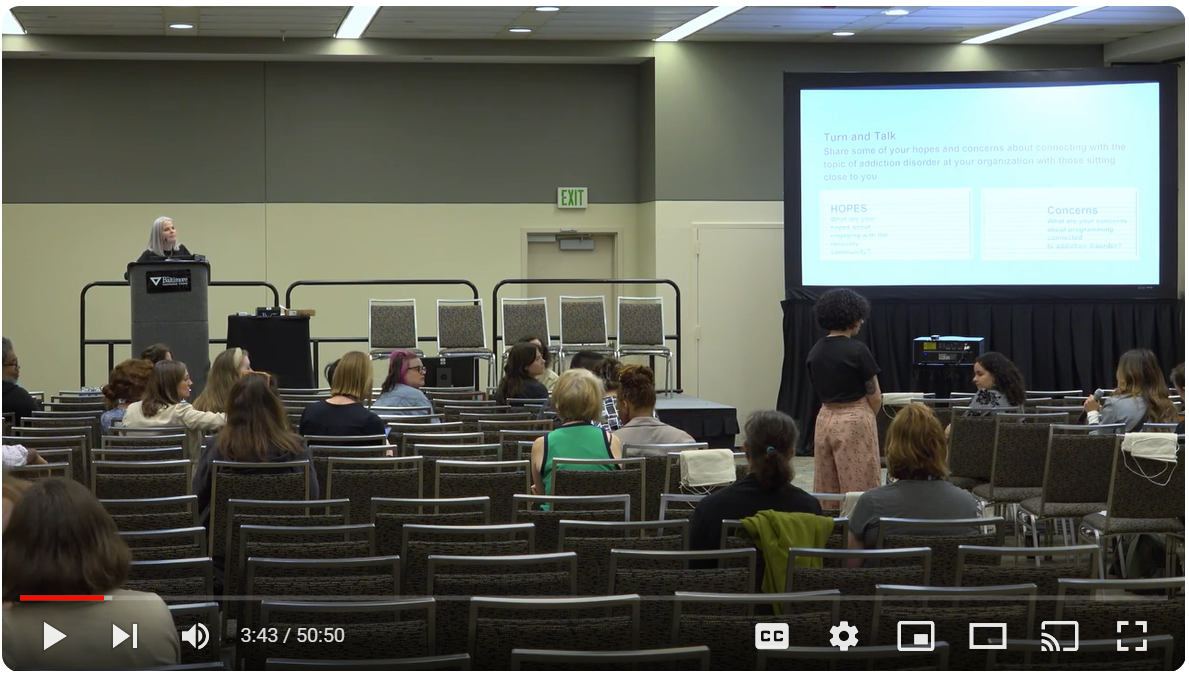

Patty Bode: Thanks, Zoe. Like Zoe said, I’m Patty Bodie. I’m the founder of the Remember Love Recovery Project, which is the project that we are going to be talking about today. I’m also associate professor and coordinator of art education for Southern Connecticut State University, which is in New Haven, Connecticut. But we want to really thank you for choosing to come to a session with de-stigmatizing addiction disorder in the title. It’s a topic that many people turn away from and we thank you for leaning in.

And so, we want to start out with your index card. They’re on the ends of these chairs here with little banners are hanging. You can grab one if you don’t have one. We’d like to invite you to fold your card in half and write hopes on the top and concerns on the other half like this and just take a moment to jot down what are your hopes about engaging with the recovery community on your hopes half of your index card and what are your concerns about programming connected to addiction disorder in your role, whatever that may be, any hopes or concerns.

Just taking a moment or two to jot that down and wrap up. We know there’s a lot to think about and a lot to be hopeful about and concerned about.

We just wanted to give ourselves that chance to notice that. So, with that in mind we’d like you to find somebody you’re sitting near and share some of your hopes and concerns about connecting with the topic of addiction disorder, and we’re using addiction disorder. We know there are many different diagnoses under that umbrella. The topic of the Remember Love Recovery Project is substance use disorder, which has to do with both legal and illegal drug misuse disorders.

I use addiction disorder because a lot of time when I say SUDs or substance use disorder, which is the DSM manual’s diagnostic term. A lot of people don’t know what I’m talking about. So, I tend to use addiction disorder as shorthand. But whatever your hopes and concerns are to turn– if you could find somebody near you, do a turn and talk. It was– we call it in the PK12 classroom, where a lot of my expertise is from. And talk about this prompt here. Share some of your hopes and concerns about connecting with this topic at your organization within the role that you’re in.

We’ll just take just a couple of minutes on this, please. And then we’ll see if any of you wanna share, one or two or three of you wanna share what you talked about. We’d love to hear from two or three of you,

something that may be bubbled up that you wanna share. Anybody who wants to share anything that bubbled up Within your small group, Zoe has a microphone if you’d like to share to the large group.

Any of your hopes or concerns?

Liliana: Hi, my name is Liliana, and I’m creating a show about addiction.

It’s called Faces of Addiction. And my main concern is how to deal with artists that they all have some sort of addictions in a way that I don’t expose them, so they want to talk about it, but I want to talk about the right way. That’s my main concern, and my hope is bring it right, and it’s about that this affect everyone if you don’t have an addiction, you have someone that you know that is affected by. Yes, thank you for your work, and thank you for thinking about that particular vulnerability of the community who are those who are struggling with addiction disorder and their exposure and that has a lot to do with the stigma and not in the way our society.

So, I think your show will help with that. Thank you.

Patty Bode: Anybody else wanna share something? We have someone here, Zoe.

Miguel Ordeñana: Hi there, my name is Miguel Ordeñana we’re at the Naturalist Museum of LA County.

I help run the community science program there and we get people engaged in research on urban wildlife and we have a particular project that looks at bats that live under freeways and there’s a lot of overlap there with houses communities and some of which suffer from addiction issues and so I want to figure out how to better serve that community, be more respectful of them and make them you’ll seen and supported and not just in the background and invisible and but I’m not I don’t know if it’s gonna be bad education but at least I want to be sharing space in a more respectful manner and better be a better service to them.

Patty Bode: Yeah it’s really a fascinating interface you have there with our wildlife and where they have chosen to be and are unhoused, those, again, who we turn away from. And there is a huge co-condition rate of– and there’s a real chicken and egg with addiction disorder and the unhoused.

So again, thank you for heightening that. Maybe something we say today might be helpful, we hope. Anybody else before we move on? We’ve got one more, Zoe, just behind Miguel there.

Thank you.

Cynthia Lee: Hello, my name is Cynthia Lee. I actually work at a public health institute, but I am a museum studies student, so I have done a lot with substance use disorder as well and now programming. I think some of the hopes of engaging the recovery community with other non-traditional stakeholders is, I think, not only building individual resiliency, but community resiliency, not only on a smaller scale, but on a larger scale. But I think whenever working with people with lived experience in various aspects. Some of the concerns is like, how do we not only bring them to the table, but also uplift them into decision-making positions and actually leading these processes and programming?

Patty Bode: Beautifully stated with great insight. Thank you for that. So you have a lot of common goals, all of you, with what we’re gonna talk about today. So, that really leads us into this question that I think A lot of people ask about the Remember Love Recovery Project.

Why addiction disorder? Why the recovery community? Why arts activism? And why Remember Love? The Remember Love Recovery Project is an arts activism nonprofit about to become a nonprofit.

I should say, we’re just weeks away from getting our IRS paperwork. Our mission is to de-stigmatize addiction disorder through art, education, and human connection.

And again, why addiction disorder and why the recovery community and why de-stigmatize. To de-stigmatize means to remove associations of shame or disgrace.

We know that the stigma is what rips apart the human condition. It is what creates isolation. It is what actually kills people. Of course, we can say that the misuse of the substance kills them, but we know that the isolation is an exacerbation of a previous brain condition. We learned a lot about brain research today, and there’s a lot to support this. We want to remove shame or disgrace, and keep in mind that the opposite of disgrace is to give grace and to consider our role in that.

We want to destigmatize addiction disorder because over 100 ,000 lives are lost annually to overdose here in the United States of America. This is the only country in the world where this is true, where the percentage of loss of lives to overdose is so high. It’s astronomical. That means it’s a social condition, that means we can change it. One of the ways we can change it is to destigmatize so that we can change social thought, so that we can change policy and get people the help they need. For example, our USA government research tells us that for Americans, meaning USA, Americans is what they mean there.

Ages 18 to 45, the leading cause of death is fentanyl overdose. We are unique in the United States on the planet for this to be true.

That is a social problem, it means we can change it. My son, Ryan Bodie Moriarty, died of an accidental heroin overdose in June of 2018.

We’re about to come up on the sixth-year anniversary of passing. We want to de-stigmatize addiction disorder because the opposite of addiction is connection.

So, we know that art making can create human connection. We also have deep scientific research from psychology, sociology, medicine, and psychiatry.

We want to de-stigmatize addiction disorder because the war on drugs has criminalized Black, Indigenous, and other people of color, including Latinx and other marginalized communities such as LBGTQ+, disproportionately resulting in catastrophic incarceration rates. We want to destigmatize addiction disorder because our opioid crisis in the United States has been caused largely by pharmaceutical companies lying about medical research who are still making billions of dollars from their lies.

This is also unique to the United States. We want to de-stigmatize addiction disorder because we’re hopeful. And we know that recovery is real, addiction is treatable, and we have the science to show what works. We need the political and social will to do so. So why arts activism?

One of the reasons is Because my son, Ryan, was an artist. And I was a career public school art teacher. I’ve been in the public schools for over 20 years as an art teacher and a school principal. I’ve been in higher ed teaching people to become art teachers for over 15 years.

This is my life, is art education. You can see one of Ryan’s drawings, guess who that’s a portrait of? He was also a ceramicist. He was also and avid and deeply practiced and widely performing musician from the time he could hold the instrument in his hand.

He was a banjo aficionado, as well as a banjo researcher and guitarist. He was a writer of songs and poetry. And he was a t-shirt designer, and he was kind of famous for making hand-printed t-shirts and selling them at music festivals. And this image, remember love, was his most beloved design. And people are wearing it all over the country, who have purchased them from him at music festivals. So why remember love? When Ryan died, and we had to clean out his articles of possessions, of things he cared about, we stumbled upon the a block that he made the remember love design with. And we said this is a message he left us with.

We’ve thought deeply about that. You can see more about that on our website about all the ways in which remember love means something. And our most assertive statement is that to remember love is to affirm the human dignity and worth of people with addiction disorder.

And the family and friends who care about them, thank you. And so we took his linoleum block and we printed hundreds of posters for the celebration of his life to give away to everybody.

And when they were hanging in my backyard on the clothesline, I thought, prayer flags. My family is deeply connected to the Buddhist tradition through part of our family who comes from Cambodia.

And our families are intersected with our different faith beliefs and practices. And our family has visited a place called the Peace Pagoda in western Massachusetts frequently, which is a space built by Buddhist monks in collaboration with Vietnam vets against the war. So Prayer flags have a deep place in our hearts. And I was taught by the monks that the prayer flags’ purpose is to pour one’s compassion in goodness into the flag so that it goes out to places in the world where it’s needed.

And I thought, what if we had remember love flags or something that could do that about addiction disorder. What if we could pour our compassion?

What if we could change social thought by making flags? I spoke to the monks and I talked to them about it and I got their blessings, both spiritually and physically, to start a project that I call recovery flags, not to appropriate the Buddhist tradition. That is not what we’re doing, and the word prayer doesn’t resonate with everybody. But the notion and the inspiration and the intersection of this idea, along with another important cultural marker in my life, inspired me. When I was a young art teacher, I participated in and helped propagate the message of the AIDS Memorial Quilt.

These photos are from 1987, when the AIDS Memorial Quilt was brought to the Washington DC Mall, when the stigma of AIDS is what turned our society away and did not rely on the science of what could happen for healing.

And I thought, what if we brought tens of thousands of recovery flags to the Washington DC Mall? Because a printmaker’s urge, of course, is to reproduce.

And I thought to remember love is reproducible. How can we do that? So my goal is to make tens of thousands of recovery flags and bring them to the Washington DC mall.

And we’re going to move on and tell you a little bit more about how that’s happening. Thanks to Zoe and her work.

Xoe Fiss: Thanks Patty. So, I’m really, I feel very lucky that I got to be one small part of Patty’s story. And I’m going to tell you a little bit about me and my work and why I felt this was a really important project to bring to the museum I was working at in a small town in Wisconsin.

So just to place ourselves where I was, I was there for about six years, an hour north of Milwaukee. Sheboygan is a little town known as the Malibu of the Midwest.

We’re a little bigger than most people think we are. The whole counties altogether are almost 120 ,000 people. There’s some really sizable companies out there, Kohler Company, Acuity, Sargento, so a lot of influx of new people and a lot of people who have been there for a very long time. And that’s a picture of the really cute little charming downtown. Right smack dab in downtown is the John Michael Kohler Art Center, and I was really drawn there because my educational philosophy is very much connected to the amazing community-based work that they have been doing for a very long time. That the bigger picture is the main building, which has since had two additions on it during its growth, but it opened to the community in 1967 and has a lot of really impactful, long-running programs.

I was really excited to be a part of that work. It’s taught me a lot about community engagement. The lower picture is the John Michael Kohler Art Center’s Art Preserve, which I think is also a really important part of its story as well.

And I encourage you to look at the work that they’re doing. But I’m just going to focus on two areas of my work during my time there. I had the role of Education Program Director.

So that meant my role was to work with ages seven to older adults. So truly was working with my team to do everything from school tours, teacher professional development, community engaged, artist residencies, teen programming, and work with older adults. I mean truly anything and everything. And when I started, my passions were really in thinking about audience centered Programming and I was really excited to specifically connect with the disability community I was really thinking about communities that were fairly invisible in towns like Sheboygan It’s so often that folks find themselves in day programs and don’t have access to Spaces like the John Michael Kola Art Center, which is free to the public I like to think about spaces like that as third spaces like libraries instead of books There’s art and there’s a lot of great social exchange that can happen there. And so one way that the Art Center facilitates that is through the social studio.

It’s a really large drop in space, directly across from the gift shop, the same size. It’s pretty amazing, right by the front door. So you don’t have to go down to a basement. You don’t have to decide, oh, is this for kids?

Is this for adults? And my team and I worked really hard to even make it more kind of adult friendly as well. really encourage that multi-generational collaboration that can happen in a space like that.

So, here’s some pictures of that space. We worked on a couple community sort of mural projects guided by artists. The mission of the John Michael Kolar Art Center is to create, generate creative exchange between artists in the public. So, everything we did had an artist involved and that very much led to my work with Patty. And here’s just some more pictures to set the scene of this space.

So, every summer in Sheboygan for over 50 years, the John Michael Kola Art Center has the Midsummer Festival of the Arts, which draws 15 to 20 ,000 people for the third weekend in July to enjoy art vendors,

music, and art making. That’s one really cool thing that the Art Center does during MFA is has free drop-in art making. And one of the tents is a community engagement tent where an artist is often doing a very community engaged project.

It’s not a foreign thing to the art center. One thing that they do that really grounds this work and kind of helps guide the programming as well as they choose a theme for the year. And so the year that I connected with Patty, which it hasn’t even been a full year, was Ways of Being and we were really thinking about how we’re all very much connected to one another. Just to show you some other examples of how the Art Center has done this work, and just the year before Patty and I worked together, we used MFA as a platform to amplify community voices and so it was amplifying the work we were doing with the disability community. This was in connection with an exhibition that was on view as well.

I think really capitalizing on those high attendance events and knowing that people are already coming in for one experience and then presenting them with a way that they could connect together in an unexpected experience can be a great opportunity to consider for your institution.

We also, the same summer, Patty, was there last summer, brought in emerging artists as well into that same indoor space, really thinking about how art festivals can be more accessible to artists who are new to the field, sometimes there’s cost barriers. So really in thinking about this work, it’s one small part of a greater thought of how can museums be more accessible spaces.

But a really important part of my personal story is as I think about my hopes and concerns about the recovery community, I think about my partner, Ben. He’s almost ready to celebrate eight years sober.

And we have a really beautiful relationship where we care so much about our community together, but I’ve never seen our worlds colliding. I never really thought like, oh, how can I work with the recovery community specifically in my work?

He was just doing his thing, and I was doing mine. And then the Art Center showed the documentary Love and the Time of Fentanyl, and I dragged Ben. It was like 6 p.m. on a Thursday, and I was like, we have to go to the Art Center because I really believe that your space is that you’re working, the museums in your community are a great place to continue your learning as well and see what your community’s interested in. And the performing arts team did an amazing job bringing in different facilitators at the end of documentaries.

And they brought in folks from Lighthouse Recovery Community Center. I drove past this building, hundreds of times had no idea what it was. It was three blocks away from the arts center. And they came and facilitated an arcane training, talked about their work in Sheboygan, and I walked away saying, okay, Why am I not doing this? So that was February. Patty came to Sheboygan in July. It was a really quick turnaround.

I went to the National Art Ed Association Conference. I went to Patty’s presentation, which you all just heard an abbreviated version of, was floored, went back to the Art Center, and luckily, I had the organizational support to really do some work that might feel a little risky in museums, you know, and say I really truly believe that this is important for us to engage more deeply in this work with the recovery community.

And so, I’m happy to pass it off to Patty so she can talk about what that experience was like coming to Sheboygan.

Patty Bode: Thanks Zoe. It was really amazing going to Sheboygan. I had been working on the Remember Love Recovery Project in every prison in Connecticut, which I’m still doing. Several homeless shelters in Ohio. Several small recovery sites and lots of private places, people’s backyard birthday parties and anywhere people would want to make recovery flags and consider destigmatizing addiction disorder and have a conversation.

Everywhere I went I always asked to work with clinicians or care providers to either provide education, provide support, distribute Narcan naloxone like Zoe was just talking about.

And it was really profound that Zoe called me up a few days after the National Art Ed Association conference was over and said, “Let’s have a conversation about what we can do together.” And everything that I asked for, that I was interested in partnering with local recovery sites or communities such as Rogers Behavioral Health, Mental Health America, and Lighthouse Recovery Community Center, Zoe facilitated and made happen. These are some of the therapeutic counseling staff. You can see them greeting us, helping us bring the art supplies in with our team. These are, like I said, the therapists, but they brought me in and we, Zoe side by side with me with her team, helped work with the clients in making their recovery flags.

Mental Health America, worked with volunteers and their staff and some clients. We went to Lighthouse Community. There’s Julie, who was directing it at the time, and we had this beautiful outdoor space to work with the clients there.

And I learned so much about the community and what they’re doing to support people with addiction disorder. And then importantly, after two full days of working in the community, the Midsummer Festival of the Arts that they call the MFA at the Kohler was happening and Zoe provided this giant tent that seated about 80 people and over the course of two days more than 700 people came in and Julie and the folks from Lighthouse came and distributed Narcan right next to our welcome table where we welcomed people to come in and I And I told my story.

I have kind of an elevator pitch form of two minutes. And every single person who came in heard the story. If you want to see a little bit more about all of this, it’s in the museum magazine that was just issued last week.

We co-wrote a story about it. Here’s a few photographs from that weekend of some of the flags that were made. You can kind of capture the spirit of the tent. As people made and we hung them up.

And here’s the team. And I was the other thing. There was a team of at least I think 10 helpers with me at all times. It was like amazing non-stop worker bees, which was really essential in other community members, such as Koki, you see here with Zoe, doing all kinds of important work. This gives you a little glimpse of what Some of the results were this was after the first day because you can see there’s two rows of flags going around this ginormous tent and by the end of the second day there were four rows of flags going around and We almost ran out of flags.

So we know for sure. We made over 575 flags that day We always invite people by the way to take flags home with them and keep them or give them as gifts As we know many people like to do that But we also tell them if they decide to donate it to the project, our goal is to bring it to the Washington DC Mall. So that was kind of the overview. I could say so much more about how Zoe helped facilitate it and this collaboration between community activism and a cultural institution.

But we’re going to talk more about your institution now.

Xoe Fiss: Yeah, thanks Patty. I also forgot to give a shout out. That was Ben and his mom in that picture, if you read that little cut line there. So that was my partner, the project at MFA. But I do really just wanna echo and emphasize what Patty’s saying is this project couldn’t have happened without the support of the Art Center and having a really great team who had total buy-in into it.

I worked with a team of amazing educators who really gave it their all to support Patty that weekend. So, It was a really special experience. But that’s not always possible to have that support and have a large program to do this at.

So, I want to give you all a moment to either audit, reflect on a program you’re currently doing, or think about your space and place and how you might bring something like this into your museum, whether it connects to the recovery community or maybe another invisible audience that you can identify in the community that you’re based in. So hopefully that all makes sense.

We want you to really think about what voices outside of the museum are you aware of, and maybe you make some notes to yourself of how are you going to find out the voices that you don’t know about.

You know, I very much had that experience of not knowing that an organization was three blocks away, but it actually works for Rogers Behavioral Health, so I very much knew about them, and that was an easy connection.

But spaces like Lighthouse can sometimes be small, and you don’t necessarily know that they’re your next door neighbor. So maybe jotting down some notes to yourself as well about how you’re going to find those support partners in whatever project you want to do.

If you aren’t interested in writing on the worksheet, if you’re someone who rather would not have paper and you have a different notebook, these are the questions that are at the top that we’re suggesting that you consider. Whatever works best for you to have like four or five minutes of reflection at this point to kind of take whatever gears are turning in your head and get it down on paper while it’s fresh in your mind. So please do let us know if you have any questions and we’ll come back to you in a couple minutes to take some shareouts. I hope some of you will share what you’re thinking about right now.

[A few minutes pause]

Yeah.

Patty Bode: What’s bubbling up for you? What, bubbled up with this? Anybody want to share something? Yes?

Audience member: Well, I have– it’s kind of a question, and I’m curious to hear from anybody. But one thing I wonder about is institutional pushback for any of this kind of work?

Xoe Fiss: Yeah, it’s so hard to answer ’cause I think it depends on the context that you wanna do the program in and who you wanna work with. I think the Art Center’s a really unique place because it is so mission driven to both be community connected and I think also have a national presence as well.

So, there is that kind of lens on the Sheboygan community quite a lot of the time. I think there’s ways to definitely start smaller though and have proof of concept and I found success in other programming of just starting first to gather information.

So, I’m actually doing that right now in my role. I’m so new, I’m just trying to figure out how do I take this very strong foundation of programs and figure out how to grow them and what do our family groups really need and what does family mean in the Milwaukee community.

So, I’m taking some time to do family studies and also talk with organizations that I’m seeking out to just ask them what they’re doing right now and what their needs are. So, I’m starting very small with the disability community, hoping to pilot some programs that are life skills classes about how to visit the museum. And that very much fits into what they’re already doing. And so I have the organizational support from the partner that I want to connect with.

And it’s fairly low stakes for the organization. My museum, to give it a try, It’s not a huge investment. It’s not a huge public-facing program. It’s a way to see, like, is this a community need?

Is this something people want to do? So, I encourage you to gather lots of information. Use that to advocate for yourself and start small. I also think if you ever have the ability to go out to groups, I know sometimes our roles ask us to be very internal and really kind of want us to bring people into the museum as much as possible and I’m a huge believer that people don’t come to the museum unless you go out to them as well.

And so, seeing if that’s within a project you can do, whether you have an artist residency that you can make a visit one part of it, you know, and kind of start planting those little seeds, you might find you get a little bit more buy-in that way than starting like a whole rollout of a project. My other hope, though, is to, you know, I talked to Patty and others a lot about this. There’s often trends in museum education, and I’m really hoping that right along with partnering with the IDD community, with partnering with adults with memory loss in their caretakers, partnering with adults 55 +, that if all of us do work like this, every museum is going to want to be a part of this conversation, and we can really be a huge part of generating change to destigmatize addiction in our communities.

I really think it’s an important conversation for museums to be having, to make our audiences feel both seen and I think feel empowered within their community to see how museums are providing them with information that’s truly so relevant no matter where you live.

So, all of those things.

Patty Bode: Yeah, and if you see Museum Magazine, we started out the article talking about how people entered the tent.

And, you know, there were people with very young children. There were, you know, clusters of teens, right? There were all different ages from 90-year-old grandpas down to you know babies and strollers and I gave the same Welcome to everybody, but if they were if the kids were like a little bit younger than ten instead of saying my son Ryan died I would always say we’re named we’re remember love and we’re named for this design that my son made It was the first thing I say and people say oh, it’s beautiful and then I usually say yes and tragically we lost him to an overdose, you know this many years ago and I usually say he died I think it’s really important in therapeutic work to say the words death and die but if there were kids like under the age of 10 I would kind of point to the sentence on my handout and so the parent could explain that but I would say you know he’s no longer with us like so I would allow families to handle words about death and dying their own way and at the same time, I would do the rest of the intro, and everybody entered.

Everybody leaned in. There were a lot of families, you know, coming after church on Sunday with their kids and their beautiful, you know, matching outfits. There were other people just coming to hang out and, you know, get something at the food truck, listen to the band. And out of those over 700 people, there was only one person who turned away after I said it, was like, “Okay, I don’t really want to do this.” That was amazing to me, right? I didn’t wake up that day saying, “I’m going to go participate in de-stigmatizing and addiction disorder.” So, I think surprising, allowing ourselves to be surprised is also important. I know you had something.

Alejandra Peña: I’m just, well, my name is Alejandra Peña. I am the director of the Weissman Art Museum at the University of Minnesota. I moved to Minnesota to Minneapolis two and a half years ago and I made it a purpose to take public transportation for the first two years so that I could get a sense of the community and what the needs are and to try to think like, how can we help? And you know, there are a lot of unsheltered individuals in Minneapolis. There is a serious addiction crisis and I’ve been reaching out to some institutions that work with them.

There’s particularly one that I admire a lot, the work they do. They are centered mainly in helping women and they recognize addiction as a disease so they don’t assume that because you’re going to come into a shelter you’re going to stop using immediately so and you know they give support once they recover women can move in with their children there which is also sometimes a big impediment for them to to start recovery because what do they do with their children but I just don’t, this is an interest that has developed in me because I don’t think that it’s just stigmatized but it’s also a problem that is ignored and people don’t see it and people just get in their cars they never have to deal with this they never see it firsthand unless it becomes evident that there’s someone in their family and I’ve had friends whose kids have died of overdose too and I’m also concerned about the environment being around all of these young students at the university if there is someone suffering from this and what could I do I’m looking to train our museum staff with Narcan, so that, you know, if, I mean, it would be the perfect place to go into a museum, go into the restroom, and use.

So, it’s a concern that I have, but I really don’t know, like, how to make the next step, how to do this. I’ve been just, like, looking, talking, and so far what I’ve done is I have volunteered with this group and I said I’m gonna start and see what comes of it and so that’s why I was here and I wanted to hear from you.

Patty Bode: I’ll come.

Xoe Fiss: And Patty, I just want to add in two things that I think are kind of bubbling up. One, I just want to really celebrate people like Patty. I think museums can really embrace road tested projects as a way to get started and that’s a big part of what we’re presenting about today.

There’s so much that you can kind of ask of an artist and educator who’s really so knowledgeable about this and has something that is working to bring into your institution and help you figure it out.

I think also partnering with all those local organizations is a great way to start. And I think being on on a college campus, I love the Weisman. It could be great to see what students are interested.

I did a lot of work in grad school with the University of Arizona Museum of Art, and they often bring students in to help with work, and I know that that’s something that happens at many university art museums, so I wouldn’t be surprised if there’s a group of students who would love to be advocates on campus, and I think that would be so powerful to see coming from the museum. And also, I was surprised, you know, myself, just not being knowledgeable, Lighthouse Recovery Community Center will provide Narcan distribution boxes for free in the Sheboygan community. You all probably have resources within your community that would put Narcan in your facilities for free and do training with your staff.

So, I think that’s a great next step.

Patty Bode: I also want to say that I knew nothing about addiction disorder. Nothing. So, I said, but I have to do something. So let’s get your comment real quick. We’ll hear what the comments are and then we’re gonna move on, yep.

Audience member: Hi, I’m Patty, I read your article and I actually did not know that this was the room that I was coming into today, but I lost my son Amos five, six years ago in May who was an amazing artist and we’ve had nine shows of his work and everywhere we go we try to bring it to audiences of teens and for those of you in museum land you probably know that it’s hard to get teens in the door back in the door and what I’ve found is that when we work with institutions it is a different kind of ask for the institution it’s not the typical museum goer. And it really requires a lot more than just hanging stuff on the wall or installing the exhibit.

So, every time, it also is a financial commitment. I’m admiring just things like this, cost money, and so does the docents to do the work.

So, but there’s a wonderful opportunity for healthcare organizations and communities who often support the arts to become involved in this kind of work. And I just think that the two communities, the recovery community and the art community, sometimes there’s crossover, but they sort of don’t know how to talk to each other. And we’ve done some exhibitions in very stressed communities where there may be unhoused people or people and addiction or drug trafficking, sex trafficking, right around the museum or the gallery and they’re afraid to come in the door. So, I think that this idea of bringing it outside or making the institution more welcoming is critical.

So, thanks.

Patty Bode: Thank you so much. So we already have several ideas we want to hear from you and then we’ll move to our And

Audience member: One thing that was bubbling up for me particularly is wondering the merger between the arts community and I would say the STEM community already consider arts as part of STEM anyway, and really thinking the first thing that came to mind actually was brain stemology for those people who are familiar, which is actually led by a very cool friend of mine who focuses on the intersection of hip hop and pharmacology and really thinking about how all of these narcotics are described very much through music and other forms of media and using that as an inlet for people to understand what’s actually the mechanism behind all this.

And so, immediately what popped up for me were thinking about partnerships or youth education and how they understand it, but then also how to bring the recovery community also into this in a way that’s absolutely not tokenizing and really thinking about how they’re able to engage museum communities because I think that There’s a fascinating opportunity for mergers between art museums and of course science and technology museums and then as you’re thinking about how do you fund these kinds of things from my lens and thinking about federally funded research that comes behind this and so I think about I’m part of like the NSF ASL program and advancing informal STEM learning program and so thinking about research that goes to speak to this because there’s not a lot of research that really speaks about how you engage this particular community in an effective manner.

And so that’s just what immediately came to mind. So, it’s like, I’m all over the place with it, but appreciate it.

Xoe Fiss: Yeah, I love that. And I’ll just take a minute to shout out the work.

My partner, Ben, is actually currently pursuing his master’s in public health and his passion is really working within like local governments and health organizations to increase access to you know different recovery resources to that community so that might be another area to look at public health departments and kind of see what young people with energy are out there like ready to partner.

I want to really quickly yeah just But it leaves my mind, a lot of you are talking about the unhoused populations in your community and I just want to amplify, there is an amazing organization I also partnered with during my time at the Art Center called Red Line Service.

It’s based out of Chicago and it’s a studio space for artists who are either currently unhoused or have experienced being unhoused before and I can’t recommend enough for you to look at that as an example of how communities can support different invisible populations around you.

I’m just going to skip this, because this is at the bottom of your handout. And it’s also in our article as well, but it’s just kind of a summary of really things to keep in mind. Maybe hang it by your desk, kind of go back to it, and just think about, have I asked all of the questions I need to? And we really quickly just wanted to summarize what’s next for us. So again, the Arts Center does incredible work, and they’ve continued this work since I left in mid-December. Very bittersweet, but it’s always really lovely to see the work that they’re doing, and I hope that you do reach out and connect to them if you’re interested.

They’re still connecting with Mental Health America, Late House Recovery Community Center, and then there’s an amazing individual named Koki, who lives in Sheboygan, and he’s in recovery, and he’s a huge advocate for destigmatizing addiction disorder and just bringing love to everyone around him.

So, they had a screening of a film collaboratively at the Art Center together just this past February. And now I find myself in Milwaukee, so if you’re ever there, please do connect with me.

And again, I kind of explain the things I’m excited about, but I truly am interested in the barrier’s museums create by using language like youth and family and what that means and what people expect of our programming and how to have some bigger conversations within what we do by partnering with artists, partnering with community organizations and figuring out how to make all of our visitors feel seen and find the visitors who maybe aren’t walking through our door, realize that our spaces can be a place of community connection and feeling seen.

So, I’ll pass it off to Patty.

Patty Bode: And for me, what’s next is to affirm and complete this nonprofit status, which is coming up to advance our mission and our purpose.

I’ve been through a process of the past eight months of, you know, formulating the mission statement, the purpose of to reverse the diminishing of humanity caused by addiction and to end overdose. We don’t think in minimal goals when we think of purpose.

This is doable. We got people to wear seatbelts. When I was a kid, I didn’t know what a seatbelt was. We got a lot of people to quit smoking and to stop getting hooked until another capitalized movement restarted it.

So, we have to think big and All of our humanity is diminished by this loss of humanity. So, we’ve set five programmatic goals. I’m very excited to hear from our peer who just spoke about research.

So, our five programmatic goals are to facilitate the art-making workshops of recovery flags with all the goals I just talked about and the purpose we talked about and research. I am a researcher. I have a doctorate, my doctorates in language literacy and culture. I’ve published books and articles not critical multicultural ed, anti-racist education, culturally responsive education, which has been my field until recently that field certainly applies to this field.

So, my goal is to research around the human connection and art making, and I’m really excited to partner with STEM and brain research.

Youth, which you all just spoke about, is a target area for us to partner with wellness and prevention programs with youth to bring art making as human connection and art activism policy, ultimately, to change legislation, to get the funding and the help we need, and to exhibit and to use exhibits not only on the D .C. Mall but lots of other places to educate public and legislators for human connection, destigmatizing and social change. This is how we’ve been doing it. Ongoing connections with community partners and extending relationships with future plans. This is an example of an arts festival that happened about a month after I was with Zoe, and I went, oh, that’s how you do it. And these folks had brought me in, and so I hired this team. I had a grant, I hired a team. Those are nurses from Metro Health, handing out Narcan.

We made 470 flags in one day. This is on the streets of Cleveland, by the way, very different environment. Roger’s behavioral health has continued to bring me in on Zoom to work with their therapists and clients.

This Connecticut State Department of Correction, I’ve been doing at least eight workshops a month for the past two years in every security level from level one to level five.

You can look that up if you don’t know what that means, and I work directly with the addiction counselors in the Department of Corrections. In Cleveland, Ohio, 2100 Lakeside is kind of nationally known as one of the largest shelters in the USA. And I’ve worked with several other homeless shelters and other recovery groups. Too many to make slides about here. Museums and galleries, the Cleveland Museum of Art has brought me in and continues to bring me in to their community art center.

The International Art Center and Troy University in Alabama brought me in. Our youth, recently, this is just in the past month, Missoula Montana Arts Inner Scholastic there’s these are a couple links.

You can see some media about it. That was a news media The other two are little social media reels about common ground high school in New Haven and About the two high schools in Minneapolis, Minnesota where I was.

So far, I’ve been in eight states. Please invite me I want to get to all 50 so that every state can be represented on the National DC Mall I welcome you to join me anytime. I will come to you. I’m working off grants right now and I continue to just find funding anywhere I can. I do work full time and I have a very rich full family life and I just make it work.

So, making, researching our youth, our policy, and exhibiting please envision with me the National Mall in Washington DC. I hope you’ll join me. And before we leave We have a few resources to leave you with, and those are on the last couple slides. We want to emphasize that museums can play a significant role in de-stigmatizing addiction disorder and supporting the recovery community.

So, I think we’re out of time for Q &A, but we’ve got these resources here. Couple minutes? Yeah. Yes, please connect with us. There’s the museum magazine and our article. My community email is on the card you received and the little zip lock.

Please make note of this email to you because there’s only one of me and I’m doing all of that and this is kind of my favorite email. But either one will work, and this is a link to a link to the website, rememberloverecovery.org. Always type in the word remember, remember love recovery, put recovery in. If you just put remember love, you’ll get a dating site, and that’s not us.

Xoe Fiss: And I just want to add, as you’re heading out, one of the best things to do at a conference, I know we’re all split with time, is please do take extra of our cards and those handouts and give them to your colleagues who are here. We’d love for you to share with other museums and encourage them to reach out, probably mostly to Patty, though I’d love to connect with them as well. And we’d love to take if there’s any questions, we could find us after.

This recording is generously supported by The Wallace Foundation.