This is a recorded session from the 2024 AAM Annual Meeting & MuseumExpo. This workshop provides an overview of neuroarts: the study of how the arts and aesthetic experiences measurably change the body, brain, and behavior and how this knowledge is translated into specific practices that advance health and wellbeing. This experiential and immersive workshop will include lectures, group discussions, and creative activities.

Transcript

Susan Magsamen: So how many of you are at the keynote on Friday? Okay, great, great. So, my charge on Friday was to, in seven minutes, try to tell you everything that I knew, which was very anxiety-provoking. So, I wanted to slow it down today and really talk a bit about the work that we do at Hopkins, the field at large, and also talk a bit more about some of the ways that you can use this work in your institution. So just a bit about the International Arts and Mind Lab Center for Applied Neuroesthetics.

So we had a donor in 2007 who was extremely interested in understanding how the brain worked but she had one sort of criteria to Hopkins School of Medicine which was she wanted Hopkins to study how the arts changed our brains because she really believed that the arts could save us. And you know if you’re know anything about schools of medicine historically schools of medicine and the arts are like oil and water they just don’t come together they you know what’s in it’s fascinating, too, because arts funders often fund schools of medicine, but they don’t necessarily know that they come together.

And so, I was at the School of Ed. I was invited to come down to the School of Medicine to meet the donor family. The family’s– the last name is the Peterson’s. Marilyn Peterson is the mom, and we call her mom. And so, mom and the kids and George came down and she basically said, look, we will give Hopkins $100 million, but we wanna study the arts. And so, as part of what you’re doing. And so, Hopkins said yes. And they asked me if I would think about how to do that.

And so, it was really a privilege for me. And I consider this story, the origin story of neural arts, because without the Peterson funding and support since 2007, our lab would not have had the incredible canvas to think deeply about what this field could really look like. The family continues to support our lab and the field, and we’re really honored to have them be so engaged and involved in what we’re doing.

But in that work, in thinking deeply about what this field could be, we were able to talk to people all over the world. We were able to bring researchers together in different fields, and also practitioners together from different fields, and we’ll talk a little bit more about that as we move throughout the morning.

But what was really important was very early on, we saw that this could not be something that was going to be solved in a lab. We are never going to have one image that said, this is where the arts work in the brain. And if you modify this mechanism, everything’s going to work because it’s so generative. And that was a real interesting conflict in order to really think deeply about how we wanted to approach this as a discipline, as a true both basic science field, but also as a practice. And so in between those two things, what we really think about is this idea of translation.

And so, neural arts is really a translational field. So, when we began to think more deeply about that, we thought, well, what are we translating for? And I was in school of medicine, so prior to that, as I said, I was in the school of Ed, and for sure I always knew that learning could not happen if you weren’t well, both physically and mentally. So, we began to start to develop these models around thinking about intractable problems in health, well-being, learning, mental health, and then community development, thinking about the role that the arts could play in public health. So, in some ways this work, while it was ubiquitous all over the world in using arts as an intuitive way to really heal and thrive and learn. We began to try to understand that from an institutional perspective, as opposed to from the community, which in many ways was already doing so many different kinds of things.

So, our mission, as you can see here, is to amplify human potential through the arts and aesthetic experiences. And that’s a big, bold kind of statement, but we really think that at the end of the day, that’s what we’re about. That’s really what our goal is. And there’s lots of, if this is a nest, we’re nesting lots of different art forms, lots of different techniques and interventions and practices. We’re also nesting different ways of knowing and also thinking really deeply about who is using this work and in the spectrum of the way that the field has evolved from community arts workers, arts educators, thinking about neurologists, neuroscientists, psychiatrists, psychologists, creative arts therapists, which are both a practice and a field.

And so, there’s many, many ways that these experiences get used by different people for different purposes. So, our lab really began to really think more deeply about how we were going to begin to think about structuring that.

So, things that we do in our lab, we really do four things. The first is research. And we do basic research, and we do social science research, action research.

We’re very interested in, as I said, this idea of translation. And translation is really — well, there’s a couple things. What translation is in a really incredibly complex process when you’re thinking about so many different variables.

And it’s really critical that the right — the table is round and that you have all of the stakeholders that need to be there. We’ll talk a little bit more about that. But in a field like art and health or art and learning or art and community, art and dissemination, it’s very different than something like drug discovery.

Where drug discovery, if you have a molecule or you have an approach or even a tool that you think can be helpful, It takes between 15 and 20 years for a drug to come to market, but the arts are different. If you have an approach, if you have tested rigorous research around an arts intervention, you can bring that to market in a year, in two years, in three years. So, we like to talk about the arts being immediate, accessible and affordable. So how do you bring them to scale? How do you think about dissemination models?

And so that’s one of the things that’s faked into this impact thinking model that we’ve developed, and we’ll share that also in a few minutes. But the idea around how you can bring this to different communities in different ways for different purposes is something that is really wired into all of the things that we work on.

And we also think very deeply about this idea of a whole person approach and how we really look at systems approaches. So, it’s the whole person, but then what systems? At the keynote, you might remember I talked about sectors and we’ll again talk about those. But because these systems are so different and the dissemination models and the scaling models, let alone the sustainability models are so We really, really think about that as well.

And then the second is field leadership, excuse me, and the impact thinking model is a model that we built in 2017 after really, really doing a lot of kicking the tires and trying to understand how this work was really going to be developed.

We tested and learned, tested and learned, and then developed something called the Infect Thinking Model. The NeuroArts Blueprint I mentioned on Friday, but we’re gonna go a little deeper there. We are moving into two really important field leadership areas.

One is around mental health and well -being across the lifespan, and the other is intentional spaces. So, this space is a really good example of a space that could be it’s really, you know, even just thinking about the palette and the light and the sound acoustics. Space changes us and we change space and space is everywhere. We’re always in some space, whether we’re in classrooms and the museums at home in the community. And so, we’re really interested in the power of places and spaces and also in thinking about virtual spaces and how or immersive spaces and how those are really important.

And then in community building, we do a lot of different things. We do a lot of convening of stakeholders. We have a lot of partnerships. We do quite a bit of communications at a field level, at a sector level, and also increasingly at a general public level. And so, the book, Your Brain on Art, was really an attempt to begin to start to talk to the general public. And we’ll be releasing a journal, a workbook at the end of this year that’s really aimed at an individual exploration of the role of the arts and aesthetic experience is in our individual lives, and then moving that to a professional sector life. And then we do a lot of collaborations all over the world.

And then the last is outreach and education. We launched our first undergraduate senior upper-level undergraduate course this fall. We’re working on a number of certificate programs for different sectors. We do a lot of publishing, and we do a lot of conferences. So, in these four areas, we work pretty deeply in Baltimore, in the region, but also around the country and around the world. So, I just wanted to give you an idea of some of the projects that we work on to amplify how we do some of this work in those four categories.

So maybe I’ll start with the recharge rooms. So, during COVID, we were asked by Hopkins leadership, medical school leadership to help with burnout and fatigue and staff retention and recruitment because it was just such a difficult time.

So, we designed a space that’s called the Rise Center. And it is a highly immersive space that faculty, nurses, clinicians, staff use. And the capacity is at its limit already. There’s just not enough time for people to come in and use it. We have something called a tune bed. We have a biophilic room. We have an arts and crafts room that gets staffed by artists in the community who come in and help to guide different art activities. Or there’s coloring or self -directed activities that people can use, and also narrative writing is something that’s also happening in the space.

And so, lots of different types of art are being used. There’s also a contemplative and meditative space. And then we’re now starting to program different workshops and different activities for people to be able to do. And based on the success of this, we are launching a pediatric nursing space that’s opening in the next couple of weeks. That is a, gosh, it maybe is a 10th of this room for 800 nurses who really don’t have a place to come and really recharge.

So, it has many of the same elements as the RISE Center, but it’s really geared for pediatric nurses. And part of that’s going to include meditation, but also Shigong and yoga and other kinds of physical movement work that we weren’t able to do in the RISE Center. So, we’re experimenting with that. We’re also expanding this into the units now within the hospital so that people don’t have to go to a different building or a different floor but can have this idea of recharging.

What some of the findings of this that I think are really important is in just 15 minutes of being in this space from pre and post surveys we saw that staff and clinicians felt more grateful and more at ease and started to move towards homeostasis. And physiologically, we saw that cortisol levels dropped as much as 25%. So, this is in 15 minutes. So, you think about the role of this as a practice in your life.

And so, one of the things that our colleagues with the RISE Center are doing now is working on a website that has more ideas and easy prompts that people can do on an ongoing basis and these are things that you know may sound super simple like singing in your car, creating a playlist, doing narrative writing, journaling, doodling, but beginning to start to bring these very simple activities into their lives but through the lens of self-care and health and well-being and I think a lot of these kinds of things translate to the museum community.

Google, A Space for Being, was a project that we launched in 2019 with Google and Muto furniture and architect named Suchi Reddy. And the idea here– this was in Milan at the Salone. We wanted to show for the first time how neuro-aesthetics really affected our bodies. And so this was the first public public exhibition, sort of very small experiment that enabled us to show that. And what we did is we created a band. And this band took variable heart rate, respiration, and body temperature. And then we created three separate rooms. And the first room, and they were designed on neurostatic principles. So we know a lot about space.

We know how lighting, scent, sound, touch, all of these different environmental cues give us different physiological sensations and they can be pretty instantaneous. So, sound I mentioned on Friday travels at the speed of three milliseconds. So immediately you get sounds. Sent is like that too. Vision is a little slower. or hearing, sorry, touch is pretty quick, but you’re not always in a space where you’re feeling comfortable touching. So, we created these three rooms.

The first was kind of a relaxed room. It looked like almost like a cave. The next room was what we called Vital. It was very energetic. It had a citrus smell to it. We had lots of primary colors, very much like a children’s museum where you just felt very alive when you came into it. And then the last room felt almost sacred. It had very high ceilings. It was up lit. We actually created pieces of art that were charcoal paintings. So you came in and you smelled what you might have thought of as like burning incense in a church or something incredibly sacred. And you had a sense that you were in awe and that you were in a space where you were part of something bigger. So, each space really moved you in a different way.

What we then took biological measures in each of the rooms for five minutes. And what we asked people to do was not talk, not use their phones, but to really just be so we call it a space for being just be in a space and I think in some ways it was quite profound because a lot of us don’t do that right for five minutes we’re always multitasking we’re always thinking about something we’re not attending we’re not intentional in our spaces so we were able to get really good biometrics from each of these three rooms and then we asked the participants a simple question, what room did you feel most at ease in? What room did you feel most comfortable?

So, 58 % of the people that came through the space said the room that they felt most at ease in, their bodies said something different. And I think that’s pretty amazing that, you know, half of us, more than half of us in this experiment really were not connected to their bodies. They said, they saw something, and they thought, oh, yeah, this would be the room that I would feel most at ease in. This is a room that I think I feel good in. And the point of the experiment was to say that our bodies are feeling all the time.

And there’s a great quote by a woman named Jill Taylor that says, “Most of us think of ourselves as thinking creatures that feel, but we’re actually feeling creatures that think.” And when you think about that, it’s amazing because we often are in our cognitive minds, we’re influenced by trend, we’re influenced by what other people say, we make decisions that aren’t tied to our bodies, we’re not in our bodies. And so, people coming out of this event had profound reflections and I think a bit of insight around what if I was really in my body, what if I was really feeling myself and knowing what was happening, what decisions would I make in all of the different spaces that I’m in.

And I think the other thing that’s interesting is that Each of the three rooms, the percentage of people whose bodies did feel at ease, calm, is a third, a third, and a third. So, the other takeaway here was that we might have all thought, well, 90 % of the people are going to feel great in that first room because it’s cave -like, it’s warm, it’s womby, but they didn’t. It was only a third of people felt most comfortable in that space.

And so, the takeaway there is that we feel different from each other based on where we come from, what we know, all kinds of variables. And so, what’s beautiful to me might be beautiful to each of you, but if we talked about it, you might say it’s beautiful for a different reason. And so this idea that beauty — and that’s been proven, interestingly, in a prefrontal cortex experiment that was done in the early 2000s by someone named Samir Zeke that well it’s the same part of the brain that’s interpreting how beauty translates to us. It’s not true that what we think is beautiful is beautiful for the same for the same reasons.

We’ve also been doing some really interesting work in set and setting which is the environment around at this point psychedelic experiences and so we’re interested in what are the conditions, what’s the induction for coming into a new space where you want to have a therapeutic experience and you could translate that to anything, you could translate that to chemotherapy, set and setting, creating the space where you’re having some kind of medical intervention but in order to come into that you need to create a specific kind of environment that helps your body ready for that experience.

And so, what we’ve been doing, there’s three universities right now, McGill, UCSF, and Johns Hopkins, and we’re working with Johns Hopkins to create five different playlists. And these playlists, and again, I’m gonna extrapolate this to your experiences in museums, what kind of music is played, what kind of sound is there to induce the kind of openness or focus or presence that you’re looking for as people enter into the spaces that you’re creating.

So, we’ve created five different playlists. The first is sound, just nature sounds, water, air, rain. The second is indigenous culture sounds, so didgeridoo, drumming, and these are all sounds that are made on traditional, some of them are quite ancient instruments, flutes, things like that. The third is a playlist that was created about 20 years ago by someone named Bill Richards, who has been the gold standard for psychedelic experiences. And then we’re doing one that is autobiographical music. So, we’re working with people in this trial to pick the music of their lives, the soundtrack of their lives. And then we’re organizing them in a narrative to move through an experience. And then the last is just a random playlist of just things that the researchers are just sort of kind of putting together, no reason just kind of putting it together.

What we’re seeing early on is that autobiographical music is the most salient. It’s the music that is creating the most sort of neural activity. And we’re looking at this in two different ways. Our first experiment is looking at these different soundtracks using EEG, FMRI, and other kinds of biomarkers. And we have a hypothesis that really salient music that changes your brain is as changes the same structures and the same mechanisms as something like a psychedelic or even a pharmacological intervention and so we really not everyone’s gonna nor should they have to be having a psychedelic experience but we all can use music in different ways, especially if we can create our own playlists. So, we’re working with someone in California right now who really believes that instead of taking a vitamin or a supplement in the morning, you’ll actually get up, you’ll put on a headphone, and your body will calibrate to these different brain waves with sound to actually bring you back into homeostasis.

And based on the way that the music and the sound is regulating it, maybe autobiographical music, but it may also be these frequencies that help to get your body back into balance, so when you think about the future of this field, some of this early work that we’re doing is really beginning to sort of lay the groundwork for that, and maybe I’ll just spend time with one more that I think is really a beautiful project called One Book. This is a project that we did in Baltimore over the last five years with the libraries and the school system and a lot of cultural arts organizations in the city.

It was funded by Tiro Price Foundation here in Baltimore and it was to address youth concerns. So, we put together a youth advisory council of seventh, eighth, and ninth graders. And we just said, you know, what is it that you’re worried about? And in this first two years, The biggest concerns were gun violence,

gun and street violence, and they really wanted to talk a lot about that. So, in that conversation, and this is really about youth voice, a lot of our work starts with voice, starts with people with lived experience, and a little bit later we’ll talk about ways of knowing, but it’s really important that if you’re, nothing for me without me is sort of the motto and so what we really wanted to do was understand where youth were and what they needed from us not what we thought they needed and so they identified the first two years the youth gun violence and street violence and you know if any of you work in urban communities you know that there’s a code of the street where these kids aren’t just going to start talking about what’s going on with them. So, we felt like we needed some kind of intermediary and this is where arts and aesthetic experiences can be really helpful.

So, we picked a book with the students and we ultimately the first year we did Jason Reynolds long way down and this is a Jason Reynolds is a African-American author does a lot of work with sort of middle school age kids came from the I’m going to say Chicago, but I’m not 100%, don’t quote me. And what was really interesting is that we asked kids to do a pre and post survey talking about their level of anxiety about street violence, had they experienced street violence, what was happening in their communities, what were the things that they were most feeling, and there was a lot of physical distress, there was a lot of emotional anxiety, and really a sense that they were shut in about their feelings. And so, they read this book, it was not required reading.

We bought 12 ,000 books and we distributed them across the city and at the end of the six, eight weeks we did another gathering and we talked with the kids, they did another survey and what they sat across the board was the book made them start to think more deeply about the decisions that they were making. That there were choices that they could make, that they were able to put themselves in the role of the main character, who was a brother, the younger brother of a boy that had been killed in gun violence, in a random shooting, and that the boy wanted to avenge his brother’s death. And in this long way down in an elevator, in a housing project, the dialogue in a spoken word way, was about what should I do, what shouldn’t I do, what would happen if this happened. It was all those things that go on in our head. And at the bottom of the elevator, the boy decides that the best decision is to get an education and come back and help his community.

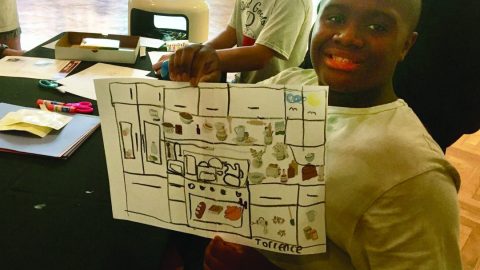

Which is a really tough decision when you think about impulse control and that age group and decision making and risk-taking behavior to kind of come to that point, but to have that internal dialogue, which is so important, you know, reaction as opposed to response as opposed to reaction. And so, it was a really amazing opportunity to use a book in a practice, in an intervention. So we took it one step further and we asked the youth if they would like to create a piece of art that reflected their experiences.

And that was extraordinary, we had spoken word pieces, we had dance pieces, visual art, all kinds of extraordinary expressions of how they felt about the book and about the topic. And we then again asked permission, would any of them like to have a showcase to be able to share this work? And they felt comfortable sharing it with peers, with family and with educators. So, think about this, seventh, eighth and ninth graders. So, we had several showcases across the city where youth shared their work and then there was lots of conversation and dialogue all over the city about what was happening.

Parents got a better understanding about what their kids were feeling without feeling that it was a parenting moment but the deeper understanding. Educators felt more connected to the kids. kids talk to each other, and it was the art that allowed them this creative expression that allowed them to feel like they could really share their voice in a safe way and I always talk about safety in spaces as certainly the absence of threat but more importantly and that’s a prerequisite the absence of threat whether that’s physical threat or emotional threat but I think importantly, this idea that you feel comfortable to share who you are, to really say who you are and to express who you are. And so, by creating work that spoke for them, it lowered stress, it allowed them to lower those barriers, those silos between each other, peers. They got to know themselves. They also got an opportunity to share with educators and with parents what was going on with them.

And so, this conversation has continued. We’ve now done four more books. The first two years were gun violence. Then we moved into character and identity. And D. Watkins, if any of you know, D. Watkins wrote a book called We Speak for Ourselves, which is about, again, he’s a black author, and talked about the way black voice had been usurped, had been hijacked by white authors and writers and people that were talking about the Black community, but the Black community wasn’t talking for itself.

And so, it really is, in some ways, a guidebook for anyone who feels marginalized that needs to find, share, and celebrate their voices. So, we did work with that book. And so, this project is continuing now to be moved into other cities. And what’s great about it, it’s one book that has made such a huge difference year over year in the community, not only the life of the kids, which is hugely important, but it’s really looked at all these different sectors and really changed the mindset of what’s happening within these youth voices and what’s happening for youth in the community.

So, we’re talking about making it for younger kids now, but it’s been a really wonderful project.

So, I think with that, I’ll stop and turn it over to Keely, who’s gonna talk us through a few more things. So, thank you.

Keely Mason: Hi everyone, my name is Keely Mason. As Susan said I am a senior research and education associate with the lab and I’m going to just give us a brief overview of what we’re going to do today.

So, you’ll see on the screen we just did an opening we’re doing an overview of our workshop right now we’re going to move into introductions after this we’d love to get to know who’s in the room with us what brought you here today and then we’ll move into what do we know ways of knowing the key concepts of neuro aesthetics. How does this impact you?

We’ll move from there to where did we come from? So we’ll talk a little bit about the history of neuroesthetics, as well as the state of the field. And from there we’ll move into how is it being used.

So, talking about how is this being used in museums today, some of the case studies, exemplary programs that we’ve seen. And again, we want to make this conversational. We want to hear from you, know what you’re doing and what you’re seeing being done in the fields and we’ll end with what can you do today again just kind of a conversation about what you are taking out of this workshop and how you can apply it to your work.

But before we do any of that I am going to ask you to do just a little bit of an activity with me so we’re gonna start with a body scan I’ll ask you to begin by making yourself comfortable. You can sit in your chair, allow your back to be straight, but not stiff. Your feet are on the ground.

You can certainly do this practice standing at another time lying down, but for today we’ll do it seated. Your hands can be resting gently at your side or on your lap. Allow your eyes to close or to remain open with a soft gaze. We’ll take several long, slow, deep breaths, breathing in fully and exhaling slowly.

Breathe in through your nose and out through your nose or your mouth. Feel your stomach expand on an inhale and relax and let go as you exhale. Begin to let go of noises around you, begin to shift your attention from outside to inside yourself. If you’re distracted by sounds in the room, simply notice this and bring your focus back to your breathing.

Now slowly bring your attention down to your feet. Begin observing sensations in your feet. You might want to wiggle your toes a little feeling your toes against your socks or your shoes just notice without judgment. You might imagine sending your breath down to your feet as if the breath is traveling through the nose to the lungs and through the abdomen all the way down to your feet And then back up again, out through your nose and lungs. Perhaps you don’t feel anything at all. That’s fine too.

Just allow yourself to feel the sensation of not feeling anything. When you’re ready, allow your feet to dissolve in your mind’s eye and move your attention up to your ankles, calves, knees, and thighs. Observe the sensations you’re experiencing throughout your legs. Breathe into and breathe out of the legs.

If your mind begins to wander during this exercise, gently notice this without judgment and bring your mind back to noticing the sensations in your legs. If you notice any discomfort, pain, or stiffness, don’t judge this. Just simply notice it. Observe how all the sensations rise and fall, shift and change moment to moment.

Notice how no sensation is permanent. Just observe and allow the sensations to be in the moment just as they are. Breathe into and out from the legs.

Then on the next breath out allow the legs to dissolve in your mind and move to the sensations in your lower back and pelvis, softening and releasing as you breathe in and out. Slowly move your attention up to your mid -back and upper back. Become curious about the sensations here. You may become aware of sensations in the muscle, temperature, or points of contact with furniture. With each out -breath, you may let go of tension you are carrying. And then very gently shift your focus to your stomach and all the internal organs there. Perhaps you notice the feeling of clothing, the process of digestion, or the belly rising or falling with each breath.

If you notice opinions are rising about these areas, gently let these go, and return to noticing sensations. As you continue to breathe, bring your awareness to the chest and heart region, and just notice your heartbeat. Observe how the chest rises through the inhale and how the chest falls during the exhale.

Let go of any judgments that may arise. On the next out breath, shift the focus to your hands and fingertips. See if you can channel your breathing into and out of this area as if you’re breathing into and out of your hands. Your mind wanders, gently bring it back to the sensations in your hands.

And then on the next out breath, shift the focus and bring your awareness up into your arms. observe the sensations or lack of sensations that may be occurring there. As you might notice some differences between the left and the right arm, no need to judge this. As you exhale, you may experience the arms soften and release tensions.

Continue to breathe and shift focus to the neck, shoulder, and throat region. This is an area where we often have tension be with the sensations here. It could be tightness or holding You may notice the shoulders moving along with the breath. Let go of any thoughts or stories. You’re telling yourself about this area as You breathe you may feel tension rolling off your shoulders On the next, out breath, shift your focus and direct your attention to the scalp, head, and face. Observe all the sensations occurring here. Notice the movement of the air as you breathe into or out of the nostrils or mouth.

As you exhale, you might notice the softening of any tension you may be holding. And now let your attention expand out to include the entire body as a whole. Bring into your awareness the top of your head down to the bottom of your toes. Feel the gentle rhythm of the breath as it moves through the body.

As you come to the end of this practice, take a full, deep breath. Taking in all the energy of this practice and exhale fully when you’re ready begin to open your eyes return your attention to the present moment as you become fully alert and awake consider setting the intention that this practice of building awareness will benefit everyone you come in contact with today.

Thank you all for moving through that practice with me.

We’re gonna move into just a brief time of introductions now, as we said before, we’d really love to know more about you, who’s in the room with us, the work that you’re doing. So, we’d love for you to first consider this question.

Has there been a time in your life when the arts have been important or impactful to you? So, we’ll take just a few moments for you to consider that. And then there are microphones around the room.

If you’d like to share your experience with the arts, what brought you here today, also sharing your name and affiliation, that would be wonderful. Good morning.

Chris Wilson: I just walked in. But this is the prompt, right? The question?

Keely Mason: This is the prompt, yeah.

I was in business school here up the street at University of Baltimore a few years ago, and all of my friends were artists, and I was really stressed out and dealing with a lot of things, and I started to go to my friend’s studio just to watch them work, and I started to learn about art. And a few weeks after that, I just started painting just to do it, and I realized when I would paint and researched the art and think about it.

I was with Go By and I wouldn’t be stressed out anymore. And eventually I sold all my companies and I just paint full time. And it’s the only time that I feel absolutely free and at peace is when I’m around art.

I try to go to many galleries and museums as possible. And I just absolutely love it and it changed my life.

Keely Mason: Thank you so much for sharing. What’s your name again?

Chris Wilson: I’m Chris Wilson. That’s my piano.

Julia Urdesi: Hi, I’m Julia Urdesi. I work at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. I am the coordinator of adult public programs and a museum educator and I run our museum mindfulness program.

Keely Mason: Thank you.

Jenna: Hi, I’m Jenna. I hate talking into microphones. I’m so sorry. I’m a third-year undergrad student at the University in Indianapolis. I’m studying art history and museum studies and I saw a painting in Florence one time and I’m Not gonna lie I cried for 20 minutes because it was so pretty and I’ve been studying art history ever since.

Keely Mason: Thank you

Audience member: I’m gonna tell you guys. I’m probably gonna cry because it makes me very happy to see this. So I went to undergraduate at RIT. I’m a museum studies major with a double minor in our history and visual culture. I currently work for the Bob Moke Foundation. So, we talk about the impact of science and technology and creative arts. Art is so important to me. It’s been in my life for such a long time. And this year’s keynote and everything has been so impactful. Excuse me for crying so much. I’m 26 and so seeing that this is a new part of our dialogue is really exciting for me. I haven’t decided what I want to do for my masters and so knowing that we can talk about these things and create such change with them is what really excites me. So thank you guys for doing this and that’s what I do.

Keely Mason: Thank you.

Erin Shapiro: Good morning, everybody, my name is Erin Shapiro. I’m the CEO of Plains Art Museum in Fargo, North Dakota. And the arts have been part of my life for a long time. I started off as a studio artist myself and it was very much that cutthroat competitive world of art and then found myself in museums and always understood the impact of the arts. Always was a champion for the arts. But then my son was born and he’s four years old, a nonverbal autistic, and that really changed my perspective on how the arts can have such a strong impact. He uses drawing and sculpture to really communicate his wants and needs and desires, and it’s really become a language for him because he doesn’t have those words, and it’s totally changed my perspective.

And Megan and I at Plains Art Museum, a lot of the work that we’re doing now is rooted in this idea of the arts as a means of communication, a means for mental health, and just a means of connection.

So I’m, you know, more grateful for the arts than ever before. Nice to meet everybody.

Audience member: I would say the first time I have a background in mechanical engineering and visual art. I started leading tours at the Contemporary and Modern Museum where I now work as the docent educator and leader of the tour program as well as our creative aging program.

And the first time that I feel like I kind of almost had an out of body art experience was when I went to the ballet, and I honestly would not have gone to the ballet had my daughter not been in the program. And I was reluctant and resistant at first. And then there was just kind of a moment at which I found that I wasn’t analyzing just what I was seeing, that I was actually seeing shapes and patterns and movement in a much different way. And it transformed the way that I started thinking about art and started thinking about it in a much more participatory practice sort of way. And I’ve dedicated a lot of years outside of my museum job to creating a robot that translates the movement of dance into a painted representation of what has happened.

And now as a PhD student in human-computer interaction also create interactive art systems that very much involve the viewer in connecting with themselves and their body in real time. So fantastic and yes I’ve had a transformational experience and I believe in it so strongly that I think it can be for everyone. So, thank you.

Keely Mason: Thank you.

Grace Belizario: Very tall mic here. Hi, I’m Grace Belizario. I work for AAM, but before I worked at this organization, I had a large background with the arts. I’ve actually been an artist since I was a child. I went to college at the Corcoran College of Art and Design when it was the Corcoran, and I was a communications director for about 17 years, So I really do know the arts are impactful.

And I knew that anecdotally, but when I worked in my last organization, the Armed Service Arts Partnership, I really got to see that up close. They did an evidence-based program where they would partner with either museums or art centers, and they would provide free programming for the military community. And what we were able to see is that when we were working with our researchers that our community members would take the classes, they would take these pre -surveys, and we would see from the post-surveys and our interview and focus groups later that they, you know, wellbeing increased. There was a little suicidal ideation. There were all these huge changes.

They were thriving in their relationships. They were taking transferable skills and applying them to their workplaces and relationships. And I could see in four years that we started the program and there were so many people that were calling for so many mental health things.

And toward the end of my time there, I was getting less and less of those calls as people were really, really thriving. And so, I’m so thankful for this session today because I’ve always been a really big neuroscience reader. I’ve taught like community things where we incorporated like touch and sensory kind of things. So, to see this happen, I’m like, I’m very excited. I’m like, love to take classes and everything. So even hearing about a certificate program, it’s like up my alley. So, I’m so excited. I’m, please thank you for continuing to champion this.

And I hope to see more of this in the future.

Keely Mason: Thank you so much. We’ll take just this one more.

Gianna Riccardi: Okay. Good morning everyone. My name is Gianna Riccardi I’m the director of education at a small museum in Miami the Coral Gables Museum. I’m also an art therapist and So my goal is to bring more therapeutic art programming to the department education and museums worldwide. And actually is started by I think I was eight years old.

My mom owns a art frame gallery. She was a framist. And I remember seeing this really big artwork, at least bigger than me at the time. Huge white canvas with a black spot in the middle. And I remember asking my mom, why did someone pay so much money for this? I was young, I didn’t know. And she explained to me that it’s not just about how it looks, but it’s about the position that the artists chose, why they chose the middle of it, why they chose the color, why they chose the size of it, and she kept on going about that and that absolutely blew my mind about how impactful and how important the process is and the concept behind the work and that absolutely drove me throughout my career, my life and becoming, well not becoming, I’ve been dyslexic and that being not diagnosed, Art was always my, you know, all what I’m saying. The outlet, there you go. Art was always my outlet to find my voice because I couldn’t say what I was feeling and that’s what I want to help our community. Sometimes we don’t know how to say how we’re feeling, we don’t want to or we just can’t.

So, using the arts as a way of communication is so impactful and I echo what everyone else is saying. It’s so great to see that this is a conversation, and it’s becoming the norm. So yay, chamioning arts.

Keely Mason: Wonderful. Thank you so much. Thank you all so much for sharing. It’s really wonderful to hear about the personal experiences and stories that brought you here today and to the work that you all do.

I know that there are so many other stories just like that, and I wish we had time to get through all of them, but that we don’t, so I’m gonna turn it back to Susan to take us through what we know.

Susan Magsamen: Keely is also a dance therapist and an extraordinary person, so it’s really great to have her here today. So, I’m gonna, I kinda feel like this is a little bit like speed because I’m going to go through a lot of stuff.

And I brought my phone just to see the time. OK, so let’s see. So, I guess I want to just– I talked a little bit about this when we were together on Friday, so I’m not going to spend a lot of time on these slides here. But I just want to go back to the fact that we have known about the role of the arts and they have been part of our lives since the beginning of humanity.

And when we captured fire and we brought it around the hearth and we circled around it and we began to tell stories and we began to move to really express what was happening.

Even I just read a really great neuroscience article about why do we do this. And it really is about this physicality of movement. And I love what you said about dance and movement because across every culture, we all share the same movements. We all share grief in a certain way. We look up when we are thinking about inspiration. We hold our hearts when we can’t contain things.

The humanness and the universality of physicality is really extraordinary, and you know in doing those things we create these neural chemical bonds so it is how we learn we understand it from an internal perspective but it’s how we synchronize with each other so movement and dance and singing all of those things that we do together that seem like an entertainment or nice to have these days are the very things that make us a community. And so, I mentioned that there are over 5,000 tribes still active around the world. And in many ways, these are the same rituals and traditions that we have brought to the modern world, but we haven’t really understood the deep, or we’ve lost in some ways that deep connection to our humanity. And I shared the by yesterday in terms of this being one of the oldest pieces of art that we really know.

And I just want to double down on E.O. Wilson’s work. E.O. Wilson was a Harvard evolutionary biologist and really extraordinary thinker, very much a comparative literature guy. And when I interviewed him for the book, it took me four times to actually get him on the phone. He’d answer the phone, and then he’d say, “Susan, Susan, it’s two o ‘clock. I have to go outside because the light is changing.” And so he’d go, “Call me back.” So finally on the fourth time, he was like, “All right, I’m ready. It’s raining outside.” And so, we were able to really talk about this idea of creativity and human connection and the imperative of this work that really showed that we are wired for the art.

So, and I think that is such an important aspect. Like we don’t learn art, we are wired for it. And the word probably gets in the way because of the way it gets commercialized, but we are literally physiologically neurobiologically wired for it. And he coined a theory that is called You Social.

And it’s an amazing thing he started with looking at termites and ants and bees. And what he saw was that these other species came together for the purpose of creating a society and also surviving. And so the individual certainly had a role, but the individual would sacrifice itself for the other, but they had to work also with the other. And in observing human species for him, he came to say that humans are one of like nine species in the planet that are you social, that really have these interesting attributes that make us need each other, and that we need each other in order to survive, literally survive as a species. And so, when we don’t do that, I think we all see what happens, but it is our nature to help each other and to be doing that.

We’ve talked a little bit about sensation and sensory systems. We could spend a whole lot more time talking about that in terms of the way our bodies are so physiologically wired to bring the world in. And I think the Keeley was helping us to kind of get a sense of that, to feel ourselves. I know when I closed my eyes, I was like, “Oh gosh, I’m tired.” You know, like, “Could you keep going?” Right? And so, we don’t always know how we’re feeling because we’ve learned to override those feelings. But sensation and perception go hand in hand.

So, think about for a moment all of the things that you do sense or the experiences that you put yourself into that might be very positive, they might be being in nature, but also the places and the experiences that you have that you don’t feel comfortable, that you’re not sure why you don’t feel comfortable or maybe for me it’s a scary movie. I hate horror films. Just the sound, just the anticipation of what is going to happen, the way, the color, and I can feel my body really not respond well to these spaces of forced anxiety or forced expectation that something bad is going to happen.

And Yet, other people love horror films and think that they’re a very fabulous form of entertainment. So, it’s not a judgment, it’s just my understanding of my own physiology.

But all of those experiences actually help to form your perception of the world. So, what you perceive is really your reality. And so all those experiences create the way that you look out and see the world and how you make meaning of those perceptions. And so, it’s sort of kind of an interesting process.

What you put in terms of external stimuli, like sight and sound and smell, they all get translated in different parts of your brain. So, the amygdala, for example, is the part of the brain that sort of says something’s wrong, pay attention, something might be happening. Well, that’s the part of the brain that something scary really ignites or, you know, something’s shifting and you really just need to super pay attention to.

The parasympathetic nervous system is the part of the nervous system that helps to regulate your central nervous system. And so, if you’re humming or singing or you’re around chanting or music that starts to regulate your parasympathetic nervous system or in also your vagus nerve, you’re gonna feel calmer. And so, these different systems within our bodies help us to do that. Touch is a really amazing sensory system where I mentioned that you have 3 ,000 touch receptors in your fingers. Those touch receptors go through the thalamus to the your cortex, and if you’re holding a child’s hand, or if you’re hugging someone, or you’re in some kind of experience where you’re feeling that sense of comfort, oxytocin is released. And oxytocin is what’s called– some people call it the love hormone, but it’s the connector hormone.

So, serotonin is another or that gets released in some of those environments. Serotonin also is one of those feel-good receptors that actually is created in your gut. And so, you think about the experiences of what you’re eating and how that experience ultimately translates to perceptions based on the kinds of neurochemicals that you’re creating.

So, sensation and perception are like two sides of the same coin. And I talked a bit about some of these experiences on Friday. But I think what’s really important to talk about here is that we now know that we have many more than five senses.

And those are not necessarily senses that are bringing the world in, although we are finding that there are new ways that we’re bringing the world in through different types of aura experiences and in different ways that we’re responding to space, and that’s because of technology. But there are the senses that are being discovered right now are the sensory systems that are interpreting what’s coming into our bodies.

So, interception is something that people are talking about more and more this idea of how we actually are processing what what’s happening kind of a central system. We’re starting to think more deeply about vestibular systems and vestibular systems are really like how you know what’s up and what’s down and how you really are able to navigate balance and more and more of these systems are starting to really be discovered.

And someone said to me recently, well, why do we need to know all about these senses or why the arts are important? And is it just because we need more funding? And I said, yes, we definitely need more funding. We need more sustainable ways to use this work.

But human body is so extraordinary. And the more we understand how we bring the world into or senses, how these synaptic connections get made, how we create these neural pathways, but how they work within us, they, I think of art is medicine, art is life, but art is medicine, and every one of you has spoken to that this morning, and I think we have not, we’ve so sidelined it, we’ve so not thought it was important, but so the more we really understand it, the more we can start to use it. And not medicalize it, you know, I think art is medicine, but medicine is also something that we do every day.

So how do we make these things normalized and practices? So, I think it’s really, you know, I’ve become a pretty much a sensory geek. I’m fascinated by the way we bring the world in and what it does to us immediately.

So, I talked about the definition of neuroesthetics and I’ll just restate it, which is the study of how the arts and aesthetic experiences measureably change our brains and bodies and behavior, and importantly, how that can be translated in practices that advance our health and well-being. And I think that we’re seeing this work show up in so many different ways.

Another sort of good visual for this field of neural arts is to show this intersection between the arts, health and science, and technology. And I love that there’s a bioengineer in the room. Technology is a catalyst for this work. Whether you’re thinking about discovery, you’re thinking about any kind of intervention, or you’re thinking about scaling and dissemination.

And so, I very much think that AI, data science, something that now may seem as rudimentary to us as Zoom has become the kinds of tools that really help us to understand and amplify this work. And so, I think we need to really begin to build better partnerships with the way technology can really help us. And I could tell a million stories about that. We talked about ways of knowing a little bit, again, on Friday. But I want to make a couple of points about this.

This work started in the ’50s in looking at ways to solve very big problems in the world. And this was started– the researchers that did this work are in London. And they were looking at, if you’re going to solve problems like sustainability, planetary health, poverty. How do you do that? What are the structures? Not the problem as a sort of topic area, but how do you get underneath of it and how do you really come at it? And I found that really intriguing. How do you think about how to solve a problem? I mean, usually you’re like, “Well, I’m a fixer.” So I’m like, I know how to fix that. I know how to do that. But how do you come to know what that process is? And what these researchers found was that mostly we usually kind of go into action.

We sort of think one, two, three. And we’re very linear in problem solving. But if you really pull back and you start to think about, what are the voices that need to be at a table to really solve a problem? That it’s not just one person, but it’s multiple people that really come at solving a problem and that a framework for doing that was essential. So, we’ve really taken that concept of how to solve a problem and move that into thinking about neuro -arts.

And so, these different ways of knowing and from artistic, which is how we self -express, how we create, but practical in that in many ways is sort of this idea around ways of knowing. And then this ancestral indigenous way of knowing that we look back to bring something forward, it’s just so critical.

And then the last and one that I think we’ve started to– not started– we have elevated to kind of be the crown is scientific knowledge, academic knowledge. But in fact, academic knowledge is a way of knowing, not the way of knowing, and I think it’s really important that we bring all of those together.

So, in the keynote we talked a bit about how you come at this and how you begin to change the way that leadership and policymakers and people that are actually have the power to make decisions understand the way that the arts are important and how you need to understand what measurement and metrics and evaluation means when you’re looking at something as complex as the arts.

And so, you know, we value what we pay for what we value and if you don’t value the arts or you don’t value a process, so part of our work in their arts is really moving more and more towards thinking about policy.

So, the scientific evidence for the arts is really clear. We’ve talked a lot about this complex physiological and neurobiological network of interconnected systems. And what’s really important about this is, you know, while you’re engaged in art form, and I, Chris, I love what you said about, you know, it really grounded you. You’re physically painting. Your respiratory system is engaged, your circulatory system engaged. It’s changing your immune system and your endocrine system. And all of these neurological neurotransmitters are being deployed.

You’re making new neural pathways. Your brain is literally structurally getting bigger. I mean, think about that. The myelination around the nerve fibers is actually strengthening thinning so that the speed of the way that you think, how fast you think, and it creates a resiliency and a prevention for long-term neurodegeneration issues simultaneously. I can’t think of anything on the planet that does that like different art forms.

And so, the more that we’re starting to unpack and understand that, you know, that people talk about neuromodulation, The arts are one of the most powerful neuromodulators, and they do different things for different reasons.

So, this is an image that’s in the book, it’s in the middle of the book, and I’m not gonna go through it in great detail, but I think it’s worth spending just a couple minutes here. So, you know, if you look at the, around the outside, you can see all of the different sort of areas of the brain, all of the different, there’s four main areas of the brain, there’s the prefrontal area, there’s the parietal, there’s the temporal, and then there’s the occipital lobe. And that literally goes front to back.

So, you know, your vision is in the back of your head. The cerebellum sort of sits below that. It’s part of what’s called the limbic system or the ancient brain. So in that bottom part, you see the spinal cord, the brain stem, the pituitary. All of that is part of the Olympic system. The amygdala is in that part of the brain. So that’s your ancient brain.

Sometimes people talk about the brain as a snow cone, where scoops of ice cream. So that’s the cone. That’s the anchor. That’s your spinal cord. Your central nervous system goes into your spinal cord. Everything activates off your central nervous system. So above that, you have this area, that’s sort of this deep brain processing area, where the hippocampus is, where the nucleus incumbents are, where the basal ganglia is. These are all parts of the brain that have amazing interpretation abilities.

And if you look at this sort of orange area, you see that’s called the saliency network. So, I’ve been talking for a while about salient experiences, about how you bring information in. But it’s these salient experiences that really change you. And salient experiences are two things. They’re experiences that you relate to either practically or emotionally.

So, you have a very deep emotional response to that experience, and some of you have spoken to that today, or it’s highly practical, and you need it to survive. You gotta remember that, that’s salient, because if you don’t remember it, you’re not gonna survive. And so, in that saliency network is where all of these sort of interesting things happen, and you’ll see the default mode network, which is in blue, starts to come through the prefrontal cortex. It’s sort of in that kind of temporal lobe in the parietal space.

It kind of moves in that upper brain space. And that’s where you speak to yourself, where you understand new information. And I’m going to share a little bit more about that in a second. But then you can see where the sensory cortexes are all over the brain.

So, when I’m talking about the somatosensory cortex and you’re bringing information into your fingers, that comes through the thalamus, which is below, and then it comes through the somatosensory cortex and is distributed around the entire brain.

So, you can see the gust of story cortex, that’s your stomach, that’s how you feel your stomach. So, all of these things don’t happen separately, they and together and they really work in harmony to be able to really help you make sense of the world in pretty rapid time. I also think it’s interesting that when we were talking about music and we were talking about scent being so important, you can see where the olfactory bulb is very close to the lympic system, very close to sort of this very primary space. So, you feel smell, right? Smell is 75 % of our emotions come from smell, which I think is amazing. And it’s so close to your primary emotional systems.

So, this is a really, you know, I think just extraordinary the way these things come together. I want to talk a little bit about the default mode network. So we’re talking about the saliency network. I mentioned the default mode network.

The default mode network is called the seat of self. And it’s part of the brain that we have not talked a lot about in science. It’s really just starting to emerge as something that is really, really interesting. So, I mentioned beauty is in the eye of the beholder. The default mode network is more prefrontal, but it also sort of borders the parietal lobe.

It’s the part of the brain that goes to work when you’re not bringing in information. That’s super, super important. It’s when you’re quiet. Sometimes, you know, a music state can do that.

It’s not the same as flow. The default mode network and flow are two really different things. It’s where you process information that’s coming in. It’s where you make sense of the world. It’s where you pattern find. It’s where you daydream. You mind wander. you really allow yourself to be able to process what’s happening. It’s where you find out what you like and don’t like.

And the thing that I want to say here is that we don’t pause enough in our lives to let our default mode networks really do what they need to do. I don’t know if any of you have aha moments in the shower. That’s the default mode network. Or if you’re on a nature walk, and all of a sudden, an idea comes to you. For me, I’m in the garden, and I’m just picking flowers. I’m just kind of weeding, and I’ll be like, oh, of course. That’s where your brain is just allowing itself to go inside. And I think we need more of that in all of the different spaces that we’re in.

Embodied cognition kind of ties to that. And embodied cognition is this idea of how your autonomic nervous system really interprets all of these different sensory inputs and it’s kind of the combination of how all of these mechanisms that you’re using to bring the world in, to process the world, how they work together. And so, this idea of embodied cognition is probably a term that you hear a bit about, but it’s really very much about, it’s a global word to really express all of this work that’s happening simultaneously from the external to the internal to the processing.

And when we bring sensory information in, we process it first at a feeling level. First you feel, then you have an emotion, and then you have a thought. And that may happen very quickly, but as we talked about earlier, sometimes we don’t really understand that feeling piece you know intuition I think is a great example of feeling intuition is before even an emotion right before you can start to name an emotion and you know right now I think researchers are saying that there are while there are eight categories of emotion we have in a subset of emotions over 30 ,000 emotions so we have a lot of ways to feel and we think, so how we share those expressions, those emotions, I think is also comes back to this idea around how we create and how we create art.

Reward systems, just to say a little bit about that, dopamine, serotonin, oxytocin are the three main sort of pleasure, reward neurotransmitters or hormones. And, you know, dopamine and serotonin in particular are so important for humanity and I think you can think about this related to how we get pleasure sometimes maybe through substances.

We find ways to feel good, to go to food as another one that can be a substance that is immediate gratification. Well, it turns out that arts and aesthetic experiences are equal to that and sometimes greater than that. And so, if we’re able to start to think about how these arts experiences actually provide these reward mechanisms, these reward neurotransmitters, and using them in different ways, and art is unlike other forms of experience, like I’ll use exercise as an example where you don’t always feel good when you’re exercising. You know it’s good for you, but you don’t always feel good.

What’s great about the arts in terms of reward systems is that they continue to happen throughout an experience for the most part, and often we go into flow states, which allow us to sort of suspend time and space, and that’s really important. And so these art experiences that relate to reward help us to continue to do them over and over again.

We don’t like to do things that aren’t pleasurable. And so, arts and aesthetic experiences that are pleasurable are the things that we do over and over again. And so, there’s a really important paradigm here related to building habit and building practices because we’ll keep doing them when we feel so good about doing them.

I talked about the elephant in the room when we were together, but I think it’s just important to restate that like arts, elephants are primal, they’re powerful, and they’re ancient, and they work on us at a cellular level. And then the third thing that’s really important about this metaphor is that if we don’t use them, we will lose them. And so, it’s really important that we continue to bring them in our individual lives, but to really think about this movement around and field building around the role of the arts in our lives, because we know how important it is.

We talked about sectors, and I think I’ll just end here for a moment to say that, you know, the arts and aesthetic experiences through this lens of neural arts are showing up in every sector.

And we’re seeing different aspects of it. So, in business, we’re seeing businesses use this for recruitment and retention. That’s smart. But we’re also seeing it for innovation and for collaboration and for building community.

In public health, if any of you were here yesterday and heard Chris Appleton talking about social prescribing or arts on prescription. We’re seeing the arts used in community to help build community and as Maria Rosario Jackson, chair of NEA spoke about, you know, it’s really important that if you’ve lost an art form, you’ve lost cultural connection to be able to have space and time to be able to really rebuild those cultural connections and we’re seeing it more and more in in the museum community.

You know, schools have been going in the other direction. We’ve been losing arts, and in some ways, we still are losing the arts, and we’re starting to see this work help to bring arts back. California has got Proposition 28, which is a mandate to have an art class in every school in the state. And so, they’re really working now to be able to respond to that on a physical level.

They need 7 ,000 art teachers, and they’re not there. And so, the demand right now is greater than the supply in California, and that’s what we want.

We want to make sure that there’s enough demand for this, that we begin to start to build career pathways, and hopefully we’ll get a chance to talk a little bit about that. Just going to talk a little bit about the,

I’m going to pass through these slides in the interest of Oh, maybe a quick tour of neuroesthetics. I will make one point here that it’s really only been in the last 25 years that we’ve been able to really begin to understand the neurophysiology of the arts.

And that’s been really important. The arts have, we’ve always known this, but until we’ve really been able to study them and begin to really understand them, we haven’t been able to have the kinds of shifts in these sectors that I’m talking about or these larger conversations that I think we’ve all known individually but to begin to come together.

Let’s talk about Samir Zeke.

Okay so the neuroarts blueprint. I’m going to keep moving on this.

I talked about this also on Friday, but this is really an important initiative. The momentum and the movement of the field is global. It’s happening everywhere. There are millions of people around the world that are using the arts every day for health, well-being, and learning. It is just happening. They’re under-resourced. They don’t have the staffing. They don’t have the funding and they don’t have the policy. And that’s ubiquitous. Even in countries that have state or federal programming or social medicine, there’s still not enough sustainability. And so, the Blueprint’s really working to do that. And what I wasn’t able to show you on Friday is the five recommendations of the Blueprint.

And I think This is super important. The first is strengthening the research foundation because we need research in all these different areas that I spoke about. The second is honoring and supporting the many arts practices.

And I mentioned earlier that can be from arts education to arts therapy to neurology, psychiatry, to building tools in engineering that are using the arts.

And so, there’s a really important career arc that offers all kinds of opportunities here. And there’s also a very important diversity, equity, and inclusion lens through this second piece that we really need to build. The third is enriching and expanding educational and career pathways.

Same thing, really big opportunity from an equity lens, but also from an access lens and being able to afford this kind of training. And then looking at sustainable funding and promoting effective policy,

and then building capacity, leadership, and communication strategies. And that’s from a sort of a professional level through to the general public. I think still the general public doesn’t really, and general public’s a funny word because, you know, general public is, there are many general publics, right? But how do you get people day to day in community centers, in senior centers, in schools, in workplaces, in all those different sectors to really understand the value of this and to begin to start to create practices that are really helping them in their daily lives.

And so that’s really important. I share the NeuroArts Resource Center that’s going to launch this fall. We’re now starting to beta-populate it, and we’d love to have all of you be part of that.

And if you just go to the NeuroArts, sorry, NeuroArtsBlueprint.org, you can learn more about the Resource Center, and there’ll be a lot more coming out about that over the next couple of weeks.

But this is a place where we can find each other, we can share our information, we can find what we’re looking for, there’ll be grant proposals, there’ll be opportunities for workshops and certificates and tool kits will all be on this this site and so I think of it as I said yesterday over Friday as a global watering hole and the same with the Community Norah Arts Coalition.

These are these will be we now have over 500 communities around the world that are queuing up to be able to be part of this community, Neuro Arts Learning community. And that can be started from a museum,

it can be started from a library, it can be started from an arts organization, municipalities are starting these. And so it’s really an opportunity to build a hyper-local response. And for me, at the end of the day, I think hyper -local community roots -based organizations are really where the action is and really where we’re working day in and day out.

I talked about the Renee Fleming. This is really important and this is going to grow. This year we gave out $125 ,000. Next year it will at least double and we’re really excited about this because it’s a place to begin to seed early investigators and I really think the future of this field is the future and so we really want to make sure that we have young investigators, young practitioners beginning to drive this field in a way that really helps to create the next generation of this. And then we talked a lot on Friday about all these different organizations that are involved and you can just see from things like the Kennedy Center and all the other performing arts centers to AARP and National Education And AMFA is an architecture group, that’s a global group. Americans for the Arts are doing a lot of policy work.

So the point I want to make about this slide is that there are a lot of sectors really involved in building this field, and I think that’s really important for the future. Do you want to go to the next one? Great.

Keely Mason: Thank you, Susan. And we’ll just move through these slides quickly too.

Just a few other examples of really exciting things happening in the field. Social prescribing, I’m sure that you all have heard a lot about this week. Other organizations that are doing this kind of work, the Center for Arts and Medicine, they are at the forefront of this field. They have been for a long-time advancing research, education, and practice in health. They started the Creating Healthy communities, arts and public health initiative a number of years ago and are now pioneering the EpiArts Lab, which is an NEA research lab.

Also, the Jamil Arts and Health Lab is established by the World Health Organization. They’re also doing really exciting research in this area. So just very briefly mentioning those, but just kind of this coalition of people who are doing research at the forefront of this field.

And just in our last few minutes together, we’re going to talk about how it’s being used. So, museums and cultural institutions are doing arts and health, arts and wellness programs all over the country. It’s really exciting. We’re going to just mention a few. I know there’s probably so many more that are represented in this room, But just to take us quickly through the Phillips collection, not too far from here in Washington, D .C., they are hosting a program called Creative Aging, and it was founded in 2011. It’s a really great example of a museum partnering with local organizations to best serve their community. So, they partner with a local arts organization, a senior services organization, and also a senior wellness center, and all of these organizations kind of bring their own distinct purview again to best serve these community members they have the arts organization brings arts integration the senior services organization has an art therapist who brings that creative arts therapy lens which is really important and then certainly the senior wellness center builds community connections you’ll see this these photos up here are from their current program which is guided meditation which they do in the gallery space.

Another really exciting program is based at the Minnesota Zoo. They do a naturally wild Qigong and Tai Chi. So, this is a weekly program at the zoo. They also really focus on partnership. They partner with local artists in the community to bring these programs to the zoo and certainly Qigong and Tai Chi are programs that focus on wellness.

They have been seen to decrease stress, increase balance, strength, simulate blood circulation. So, the program coordinators of this specific program really encourage participants to see the zoo as a place for wellness. So doing these programs and also being surrounded by nature just enhances those benefits that are already instilled into that program.

The next one I’ll talk briefly about is another really exciting program that’s been around for a while, the Fine Art of Healthcare at the Low Art Museum. They partner with the University of Miami, and they use visual thinking strategies to help educate med students, nursing students, so this is a program that promotes skills necessary for a career in healthcare, so those include critical thinking, communication, visual literacy.

It really aims to enhance medical education and nursing education. This type of work is happening all over the country. They have an exciting resource on their website that lists the different museum partners and medical school partners.

And it was last updated in 2020, so has likely changed. But there were over 70 partnerships mentioned there. Some of those are the National Gallery of Art with Georgetown Medical Center, also the Museum of Modern Art with Columbia University. Johns Hopkins does some of this work as well, so it’s happening all over the place.

And the last program that I will leave you with is based in Toronto and it’s with the Royal Ontario Museum and they offer forest bathing experiences in partnership with local naturalists and wellness experts.

So, they embark on guided walks through nearby nature spaces to immerse themselves in the healing powers of nature. Again, they really focus on partnership here, and I will leave you with that. I’ll turn it over to Susan to talk about one more really beautiful program. I know we’re coming to the close. Thank you.

Susan Magsamen: And yeah, we did talk a little bit about Crystal Bridges on Friday, but I think Crystal Bridges is a really interesting exemplar in that the vision from Alice Walton was to build a community based on arts practices and to integrate arts I think of it like a nest in every single aspect of the community and so from the bottom up she’s built a 500 acre refuge with Crystal Bridges at the center, and this is actually growing now. This museum is physically getting significantly larger, but they also now have built a something called the momentary, which is a place for contemporary art, but also for music, and now they are partnering with Heartland Health, so there’s going to be health care on the campus, on this museum campus, and then they’re also building a medical school, and the medical school is supposed to open this fall, and it’s completely arts integrated.

So the entire medical training program has art in every single course, so it’s sort of, I think, the way to think about medical training in the future, and you can see that translating easily into other fields, into any of the, into nursing. And I’m actually seeing that happening in nursing schools as well. But it’s also taking the museum out into the community. And so, I think there’s a real interesting opportunity to think about how all of these different programs in the arts can touch all of these different sectors. And I think this is a really good example of one that’s really doing it intentionally and doing it from its inception.

And so we’ve been looking at this as a really important model for museum communities, but also for the health care community. And they also work quite a bit in K -12 education and are beginning to start to move into maternal health. So, I think what’s really important and maybe a good place to end is to say that there are so many intractable issues that we can’t solve with the tools that we have at hand.

And when you start to think about how to integrate arts and aesthetic experiences through these co-created solutions, the possibilities are really endless. And so let me stop there and say thank you so much.