This article first appeared in the journal Exhibition (Fall 2024) Vol. 43 No. 2 and is reproduced with permission. If you don’t read the journal, become a member to receive your copy of the full upcoming issues.

As museum professionals we want our exhibitions and programs to be relevant and meaningful to our guests. An exhibition about glass in the ancient Mediterranean may appear at first to be geographically or culturally removed from the day-to-day lives of visitors to a museum in upstate New York. In this article, we (the authors) will discuss our process to involve a group of local community members in the interpretation of the 2023 special exhibition Dig Deeper: Discovering an Ancient Glass Workshop, focused on an archaeological site in what is now northern Israel, at the Corning Museum of Glass (fig. 1).

The exhibition opened in May 2023 and closed in early January 2024. In the aftermath of the Hamas terrorist attacks against Israel on October 7, 2023, and Israel’s subsequent invasion of Gaza, we once more engaged our local community group. In the process, we came to appreciate that even seemingly remote and “neutral” exhibitions about ancient history can be politically and emotionally charged for people today. As we reflect on what it took for us to involve community authentically in the face of rapidly unfolding geopolitical events, we share strategies, questions, and guiding principles for what helped us navigate a truly disruptive global event at a local scale.

Establishing a DEI Lens for an Ancient Glass Exhibition

The roots of the Dig Deeper exhibition grew from archaeological research conducted in the 1960s by the Corning Museum of Glass and University of Missouri on a glass workshop dated to the 4th century CE.[1] The excavations took place at a site called Jalame located about 10 miles southeast of the city of Haifa (fig. 2). Jalame transformed contemporary understandings of the way glass was made in the Roman world at a time when no other ancient glass workshops had been systematically excavated. As a museum committed to transforming the world’s understanding of the art, history, and science of glass, and in response to common visitor questions when encountering ancient glass, we wanted to take the opportunity provided by the exhibition to focus not just on what was found at Jalame and other sites, but how archaeologists, scientists, and glassmakers learn about ancient glass through archaeological methods. We envisioned the exhibition as an intergenerational space that would spark curiosity in immersive and fun ways.

In line with the museum’s institutional equity commitments to be more responsive to our communities and involve them in decision-making, we strove to bring a DEI lens to the interpretation of Dig Deeper. Social justice work in museums with holdings from this region has so far largely focused on provenance histories and repatriation, sensitivity around human remains and funerary objects, and broadening the stories represented,[2] none of which spoke directly to the particulars of the Dig Deeper project. While the colonial and neocolonial contexts of Mediterranean archaeology are increasingly being addressed in scholarly literature, that discourse is just now beginning to appear in museum practice.[3]

More broadly, our work at the museum is guided by (among other resources) the study of multiple community-informed exhibitions at the Detroit Institute of Arts conducted by audience research and consulting firm Garibay Group, and the BlackSpace Manifesto created by the New York City–based urban planning group BlackSpace Urbanist Collective.[4] Among the tenets of the Manifesto are deep listening, humility, designing with, and moving at the speed of trust.

We Missed Something

Seven months before the exhibition’s scheduled opening on May 13, 2023, we began to promote it through our website and social media channels. Immediately, we began to receive public and private comments including questions about the location of the site and its association with Israel. Social media responses included Palestinian flag icons, remarks on the “rich history of glass crafting in Palestine,” and a simple query of “Jalame, Palestine?” It was clear that, in focusing primarily on the ancient history of the site and the American academics who studied it, we had missed critical information and perspectives that were important to our audiences.

In response to these comments, we began to take a closer look into the more recent history of the immediate area in which the archaeological site is situated and were increasingly unsettled by what we found. First, Jalame/Jalamah (depending on the transliteration) is a common Arab place name, including of a Palestinian village in the northern area of the occupied West Bank; we came to find out that there was much confusion about the location of the site, particularly when we stated that it was located in Israel. Second, the location on which we were focused did take its name from a Palestinian Arab village. According to historian Walid Khalidi, the al-Jalama village (population unknown) was a hamlet whose inhabitants were likely driven out in late April and early May 1948, when Zionist forces occupied several villages outside of Haifa prior to the declaration of Israeli independence a few weeks later.[5] Third, the hill is now, and shares a name with, a jail and detention center used to imprison Palestinian political detainees, including children.[6]

It was clear that we needed to develop an exhibition that was informed by the ongoing significance and contested narratives over the land on which the archaeological site is located. We were supported by the commitment of the Corning Museum’s Equity Statement, which begins, “The Corning Museum of Glass has historically focused on telling the story of glass unrelated to issues of equity and inclusion.… By failing to acknowledge and address these exclusions, we play a role in perpetuating them.”[7] We needed to acknowledge and address the exclusion of Palestinian history from our exhibition. But how? Dig Deeper was not an exhibition about the 20th-century history of the region, and it felt inauthentic for us to make it one.

The museum invited Sarah Pharaon, principal of Dialogic Consulting, to organize and facilitate a set of community member convenings, which we called our Community Circle. Sarah’s background with the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience, Arab American National Museum, and Council of American Jewish Museums Advisory Council gave her experience and credibility with both Palestinian and Jewish perspectives. We anticipated contentious and fraught discussions, and having an external facilitator who was not a representative of the museum was critical.

To form our Community Circle, we connected with a local community member with past ties to the Corning Museum who had traveled to the West Bank for decades and built strong relationships there. Through her, we were able to make connections with additional local community members with a range of experiences and identities that touched in some way on the region in which Jalame is located.

Looking back, we’ve identified four “Rs” of our engagement strategy that we believe helped generate successes:

- Recognize different kinds of expertise: We didn’t expect our Community Members to have knowledge about glass history or archaeology. Their expertise took the form of lived experiences and connections to place that museum staff did not have.

- Relationships: We started with someone we knew, and who knew us. This foundation of engagement helped us build trust more quickly.

- Results: We focused only on what was achievable within the given time. For example, the opening date for the exhibition, which corresponded with the 75th Anniversary of the Palestinian Nakba (catastrophe in Arabic) and Israeli independence could not be changed, and we were straightforward with our Circle about that. Instead, we focused on label content and maps, which were still in the design phase.

- Reciprocity: We believe that participating in a museum project should add value to the lives of participants, both financially, through compensation for their time and expertise, and in the form of personal enrichment, learning, meeting new people, making an impact, sharing stories, and other opportunities valued by community members. We tried to remember that our goals and objectives were not the only–or even the most important–ones present in the room.

The five members of the Community Circle carried intersectional identities as Muslims, Jews, and Christians, and as a religious leader, an activist, an artist, and an educator. In three 90-minute meetings over about two months, the group examined a selection of exhibition content including maps, text panels, and object labels that the museum team thought needed additional care and consideration.

“Justice, Balance, and Non-Erasure”: Values-Based Interpretation

The Community Circle’s discussions were rich and profound, and centered on questions rather than answers. With little prompting from the facilitator, the group articulated and agreed upon a set of values they wished the exhibition would uphold:

- Common Ground: Discourse around this region often occurs with the intent of debate, not dialogue. The Community Circle saw the exhibition as a space in which difficult conversations could occur based on shared interests.

- Balance: The exhibition should include multiple perspectives presented through a lens of balance. Yet the pursuit of balance should not obscure the complexity of history and circumstance.

- Non-erasure: By prioritizing modern geographic terms as standard practice, the museum may inadvertently contribute to historical erasure. The exhibition should embrace the long view of historical and geographic identities.

- Justice: The exhibition must do justice to the past, present, and future.

This list reflects the priorities of our Community Circle in rural western New York in spring 2023, and it became our lodestar during times when we needed to make a decision but couldn’t gather the Circle members for guidance. We recognize that these values are not necessarily those of all people in our area and such values are particular to an institution’s own context and the moment at which conversations take place.

These values came into play both in the more concrete work of reviewing and editing labels and maps to appear in the exhibition as well as in the more nuanced and open-ended discussions the Circle had around nationhood, identity, and heritage. For instance, they recommended following the conventions of a recognized authority, such as the United Nations, for maps and geographic names.[8] The side-by-side juxtaposition of maps of the site in the 300s, when the glass workshop was part of the Roman province of Palestine, and the 2023 map provided layered references to complex history. A label that talked about the nature and history of the site acknowledged that it took its name from a Palestinian village, the residents of which were forced to leave in 1948. The Circle further supported the proposed use of both Hebrew and Arabic languages on the exhibition’s introductory wall to acknowledge the presence of different people in the region.

Another way in which the museum added balance and non-erasure to the exhibition was through the inclusion of contemporary glass artwork designed by London-based Palestinian artist Dima Srouji. Drawing on the long history of glass craft in the region, this series of colorless glass containers inspired by ancient vessels was crafted by the Twam family of glass makers in Jaba’, Palestine (fig. 3). The work is a commentary on the displacement of cultural heritage, artifacts, and people from their homelands. The installation featured the hollow, ghostly, ephemeral objects against a purple velvet background intended to evoke both the sterility of museum displays and the traditional Palestinian color of mourning.

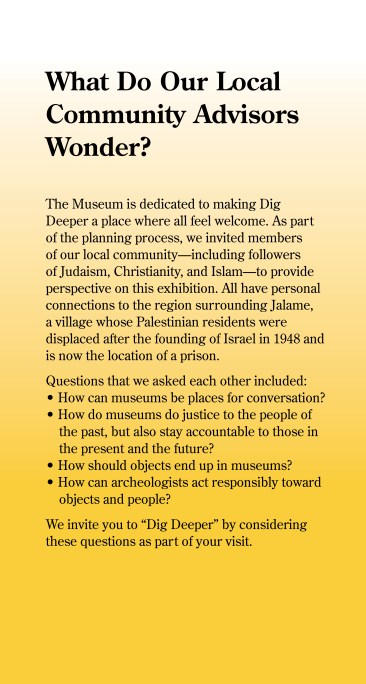

A final outcome of the Community Circle’s work was an introductory panel installed prominently at the entrance to the exhibition. Under the heading, “What Do Our Local Community Advisors Wonder?” the panel described the Community Circle process, the museum’s commitment to creating a space where all feel welcome, and an acknowledgement of the uncomfortable modern history of the Jalame site. The panel also provided a series of questions that came up in our discussions for visitors to consider as they explored the exhibition (fig. 4).

As the opening date of the exhibition neared, some members of the Circle began to organize a rally to draw attention to the ongoing injustices of administrative detention of Palestinians by the Israeli government, including at the Jalame prison. Mere days before the planned rally and the exhibition’s opening, Palestinian activist Khader Adnan–who had, at one point, been imprisoned at Jalame–died in Israeli custody following a prolonged hunger strike.[9] Representatives of the museum attended the rally to show support and bear witness. Community Circle members who organized the rally spoke about the museum’s efforts to be transparent and inclusive while developing the exhibition.

Dig Deeper welcomed almost 100,000 visitors over its eight-month run. The exhibition proved popular with museum guests as indicated by visitor surveys conducted quarterly during the run of the exhibition. Dig Deeper received a mean visitor satisfaction score of 9 on a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 being “not at all satisfied” and 10 being “extremely satisfied.” Several Community Circle members attended the exhibition’s opening or brought groups to visit. Some visitors took advantage of nearby comment cards to communicate their thoughts on the exhibition to the museum’s director. A small handful of cards voiced disagreement with the wall panel that stated that the Palestinian residents of the al-Jalame village were forced to leave in 1948. Others denied the historical existence of Palestinian people altogether. We replied to cards that included questions or that drew our attention to factual errors made by the museum, but neither criteria applied to these examples, so we read them and moved on. We did, however, interpret the remarks as an indicator that we’d had at least some success at avoiding historical erasure.

Active Disruption in Response to Unfolding Events

Within a week of the Hamas attacks against Israel on October 7, 2023, even before Israel’s subsequent invasion of Gaza and the ensuing humanitarian crisis, we reached out to our Community Circle members to check in. We hesitated to ask them to reconvene formally because we did not want to add to their already heavy emotional burden. However, the group expressed a strong desire to come back together to discuss ways to help exhibition visitors process what was happening. Daunted by the magnitude of human suffering, locally and abroad, we were unsure how to proceed.

One principle we endeavor to follow in our interpretive work at the museum is “first, do no harm.”[10] We determined that one worthy goal would be simply not to make things worse. However, our prior experience with the Community Circle indicated that we could provide space for empathetic conversations and foster local communities of care.

The Community Circle participated in a 90-minute meeting in late October. We invited Sarah back to facilitate and gave space for our Community Circle members to reconnect and share how they and their communities had been affected by the outbreaks of violence. The group expressed its appreciation for the opportunity to support and encourage one another. Bolstered by a sense of ownership and pride, they felt empowered by the opportunity to do something meaningful using the public platform of the exhibition.

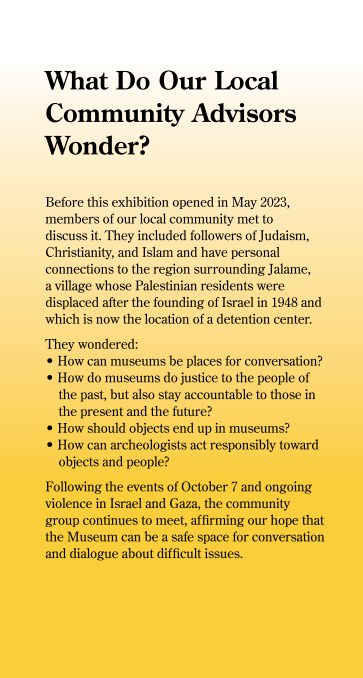

The Community Circle and the exhibition’s seven-member interpretive team agreed that the most achievable and appropriate intervention in the exhibition was the replacement of the original “What Do Our Community Advisors Wonder?” panel with an updated version that acknowledged the violence in the region and reaffirmed the museum’s commitment to being a safe space for dialogue about difficult issues. Yet, as we moved through channels of approval, we encountered unexpected pockets of internal resistance. Staff members were concerned we were taking sides, perpetuating further harm, distracting from the glass-specific exhibition content, or bending to the will of external forces. Others questioned whether the museum needed to do anything at all. There was real fear in an environment that continues to be emotionally charged.

Although initially surprised and frustrated, we came to realize that while we had tended thoughtfully to our external community members and built trusting relationships with them, in our urgency to be topical and respond in a timely way to a rapidly changing set of external circumstances, we had neglected to tend as thoughtfully and courageously to our internal stakeholders. Within the Community Circle, we had upheld the BlackSpace Manifesto principles, especially moving at the speed of trust. But we failed to adequately “do the work” internally and, as a result, people felt left behind, excluded from dialogue, and that their voices and experiences didn’t matter. We changed tactics, slowed down, and were able to successfully move forward with the installation of a revised panel before the exhibition closed (fig. 5).

The panel was installed for less than a month with little apparent acknowledgement from visitors. But had we chosen to do nothing, we would have missed some of the most valuable conversations and lessons learned during the entire exhibition process.

Reflections: The Biggest Challenges Provide the Most Opportunity

The exhibition is now closed; yet as we write, the war in Gaza is ongoing. Reflecting on what we learned from our initial foray into community engagement at a time of deep disruption, this is what we found worked:

- Start with an equity statement or policy that has been approved by the museum’s board. This serves as a benchmark for internal accountability.

- Community work is a relay, not a sprint. It takes time to grow institutionally and individually. It’s a given that this work will be ongoing. The most successful team members cultivate being comfortable with discomfort.

- A professional external facilitator, especially one that is empowered to hold you accountable, can be very helpful and is especially critical when the subject matter is potentially contentious.

- Focus on care of the community and adding value to their lives. This work is not about comfort for the museum or those representing it.

- It may not be what ends up in the gallery that matters the most, but the authentic relationships and growth that happen along the way.

As museum professionals, we often sublimate our individuality as institutional representatives in the spaces and partnerships we enter. Yet this kind of community engagement and relationship-building is profoundly personal. If we can’t enter conversations and build relationships authentically and on a human level, we can never achieve the trust necessary to share the broader range of stories we know exist.

Acknowledgements

We are profoundly grateful to our Community Circle members who were so patient and giving with us and one another. We are also thankful for the dedication and courage of our colleagues at the Corning Museum of Glass, its President and Executive Director Karol Wight, and the museum’s Leadership Team, for supporting our institutional journey toward inclusion and upholding a vision of museums as spaces for conversation and dialogue.

1 Excavations at Jalame: Site of a Glass Factory in Late Roman Palestine, Gladys Davidson Weinberg, ed. (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1988).

2 See, for example, Jen Thum, Carl Walsh, Lissette M. Jiménez, and Lisa Saladino Haney, Teaching Ancient Egypt in Museums: Pedagogies in Practice (London: Routledge, 2024).

3 Raphael Greenberg and Yannis Hamilakis, Archaeology, Nation, and Race. Confronting the Past, Decolonizing the Future in Greece and Israel (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2022); Morag M. Kersel, “Redemption for the Museum of the Bible? Artifacts, Provenance, the Display of Dead Sea Scrolls, and Bias in the Contact Zone,” Museum Management and Curatorship 36, no. 3 (2021): 209–26, https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2021.1914144.

4 Cecilia Garibay and J. Schaefer, “Metasynthesis Research: Insights from Detroit Institute of Arts front-end studies,” unpublished study, Garibay Group, 2015; Swarupa Anila, Cecilia Garibay, and Kenneth Morris, “Toward Inclusive Practice: Metasynthesis Study Findings,” 2021, online presentation of the Association for Art Museum Interpretation, accessed May 16, 2024, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oj8ZnCJh2pE; and BlackSpace Urbanist Collective, “BlackSpace Manifesto,” accessed May 16, 2024, https://blackspace.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/BlackSpace-Manifesto.pdf.

5 All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948, Walid Khalidi, ed. (Washington, DC: Institute for Palestine Studies, 1992), 167. This village appears on British-made maps published in 1878, 1881, 1929–30, and 1936. The excavations took place on a hill adjacent to the al-Jalama village, known as Khirbat ‘Asafna.

6 Harriet Sherwood, “The Palestinian children – alone and bewildered – in Israel’s Al Jalame jail,” The Guardian, January 22, 2012, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/jan/22/palestinian-children-detained-jail-israel.

7 “About Us: Equity Statement,” Corning Museum of Glass, accessed July 13, 2024, https://info.cmog.org/.

8 “Israel,” United Nations: Geospatial, Location Data for a Better World, April 1, 2023, https://www.un.org/geospatial/content/israel-1.

9 Bethan McKernan, “Palestinian Khader Adnan dies in Israel jail after 87-day hunger strike,” The Guardian, May 2, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/may/02/palestinian-khader-adnan-dies-in-israel-jail-after-87-day-hunger-strike.

10 The Corning Museum’s Guiding Principles of Interpretation state that “Interpretation efforts at CMOG will: Do no harm; Build community; Center voices beyond the museum’s; Demonstrate an ethos of reciprocity; Foster empathy and compassion among external as well as internal stakeholders; and Inspire people to see glass in new ways.”