This article first appeared in the journal Exhibition (Fall 2024) Vol. 43 No. 2 and is reproduced with permission. If you don’t read the journal, become a member to receive your copy of the full upcoming issues.

The small city of Auburn, New York, is self-styled as History’s Hometown. The community offers an incredible number of museums and historic sites. There are multiple locations dedicated to Harriet Tubman, there is a museum that preserves the laboratory where sound technology for films was invented, an agricultural museum, art museum, and more. Finally, there is us: the Seward House Museum (SHM) (fig. 1). Altogether, this network of sites drives historical tourism to the region while striving to instill pride of place.

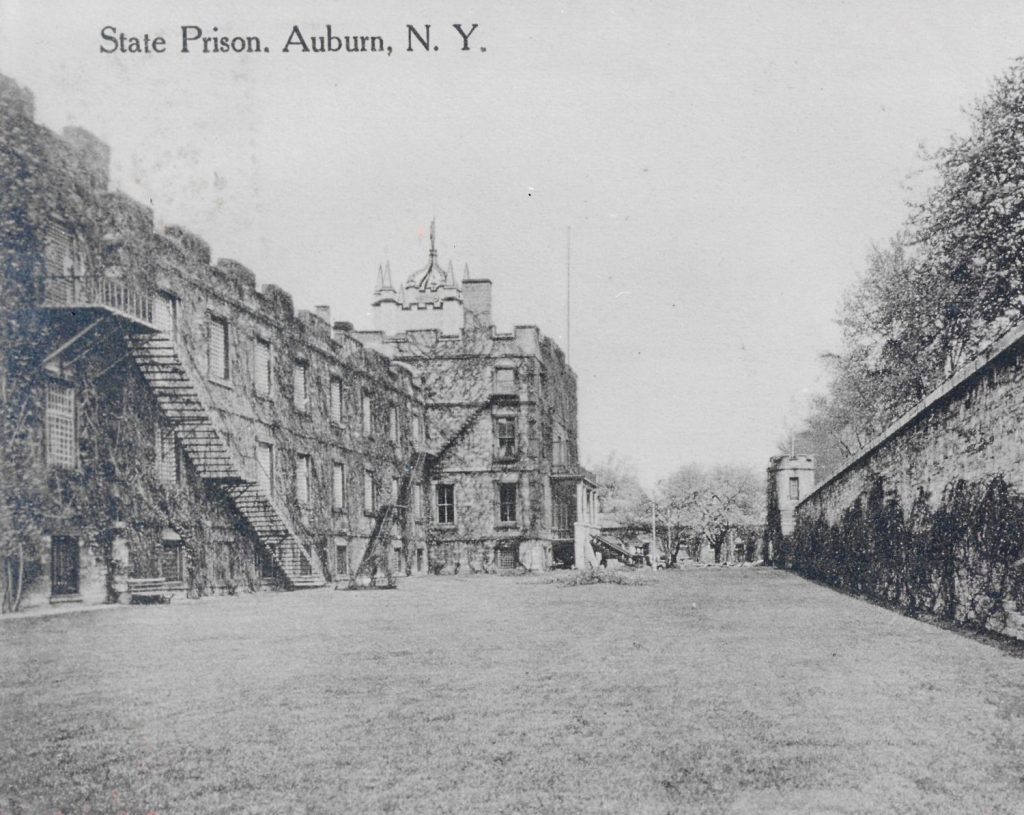

But there is another side to Auburn’s history—the city is home to the oldest continuously operating prison in America (fig. 2). The Auburn Correctional Facility (ACF), which gave rise to the original “Auburn System” of incarceration—think solitary confinement, convict labor, and (later) the nation’s first electric chair—remains a maximum-security state prison.[1] Interwoven deeply into the fabric of Auburn, the sprawling prison complex exists in the middle of the city’s downtown. Because of this, for many New Yorkers Auburn bears another nickname: Prison City. Keeping this identity separate from History’s Hometown has required a collective act of cognitive dissonance.

Although SHM was not the first local museum to acknowledge Auburn’s history as a place marked by mass incarceration, over the last several years it has deliberately pivoted in that direction. This article will explore Rooted in Reform, a new exhibition at SHM that links the Seward family to the rise of ACF, which has helped us:

- Establish new partnerships within and apart from the museum field

- Center carceral stories in our interpretation and programming

- Steer our small historic house museum away from its comfort zones.

Each step in the process was, in itself, an act of disruption, often met with internal and external resistance. As we gained clarity from the past, we set our sights on a new goal: bringing Auburn’s history to bear on contemporary debates about mass incarceration.

There were missteps and misfires—in some cases, tough lessons learned—but, ultimately, they led SHM to evolve. It also became clear that if we were going to ask our visitors to make themselves uncomfortable with the history explored in our museum, we had to start by sitting in that discomfort ourselves.

Present at the Founding

A charming yellow brick home that sits on lush gardens, SHM features one of the most intact house museum collections in the country. From when it was built in 1816 until it was bequeathed as a museum in 1951, the residence remained in the same family’s hands. At the cornerstone of its mission, SHM uses the Seward family as a lens to explore 19th-century American history. For many, this means following the life of William Seward, the antislavery New York statesman who served as Abraham Lincoln’s Secretary of State throughout the Civil War and who committed his eponymous “folly” when acquiring Alaska in 1867 (fig. 3).

In truth, the lens of the Seward family can be obligingly wide. The museum has focused it to view issues of race, gender, immigration, and suffrage. Until very recently, though, it was almost never turned toward the prison or the system of incarceration that grew and developed out of Auburn during William’s and his wife Frances’s own lifetimes. And who could blame us? In hour-long guided tours of the museum there was already far too much material to cover. Our motto: one house, many stories.

Prison stories rarely made the cut. That changed in the summer of 2021 when SHM staff were invited to Ossining, New York, for a preview of the in-development Sing Sing Prison Museum.[2] The museum professionals building that site not only shared their enthusiasm for the power of telling carceral stories but were drawn to Auburn as both the direct forerunner of Sing Sing and progenitor of American incarceration. Their work explored how systemic inequities of mass incarceration trace their roots to these beginnings, and how museums could be vehicles for dialogue and change.

We left Ossining determined to find answers to new questions about the Seward family and Auburn Prison and feeling inspired about the power of carceral storytelling. How did the Sewards understand crime, punishment, and fairness, and what could this tell us about their time and ours?

Prior to an exhibition taking shape, staff went into the archives seeking primary sources that connected the Sewards to the prison. The paper trail revealed how Elijah Miller, Frances Seward’s father (William Seward’s father-in-law), played a far larger role than previously realized. As part of the founding generation of Auburn, Miller gained a fortune, a judgeship, and an assignment from the state legislature in 1816 to “select the site for and erect the state prison then enacted to be established in Auburn.”[3]

Miller wedded his interests to those of the burgeoning prison, not only serving as an inspector once the facility was constructed, but double-dipping and hiring the same architect and master builder to construct his own house (the present-day Seward House Museum). Miller presided over and benefited from the birth of the Auburn System, exploiting convict labor in his own industrial enterprises, including a cotton mill and ancillary machine shop.[4]

Seemingly unaware of the contradiction, Miller approached Auburn Prison from a moral as well as an economic interest. A Quaker with an egalitarian streak, part of him believed that the prison could be a source for good by abolishing older modes of retributive punishment like public stocks and gallows. From there, Miller believed, a more humane method of incarceration would take root, one in which the incarcerated would be housed in solitary isolation to reflect on their crimes and where debts to society could be repaid through contract labor. In his mind, then, Miller was a humanitarian as well as a shrewd businessman; in reality, he helped give rise to a system that the United Nations would later classify as torture.[5] Clearly, some cognitive dissonance in Auburn began early.

Rooted in Reform: From Ideas to Exhibition

The themes of intentionality and unintended consequences were immediately striking to staff. Through his efforts to reform a previous era’s carceral system, Miller helped create a model ripe for abuse, exploitation, and oppression, all hidden from public scrutiny. The highly profitable Auburn System reshaped the world—bringing travelers like the French political theorist Alexis de Tocqueville to Auburn to study and replicate its design. “With its policy of penal servitude, the New York system did not just reorganize prison discipline,” the scholar Caleb Smith reminds us. “It changed the status of convicts in the eyes of authorities…they were usable bodies, stripped of legal rights, condemned to work without the prospect of gain—bound laborers under state control.”[6] In the modern ACF, where New York’s license plates and much of the state’s furniture are still manufactured, this system remains alive and well.[7]

As staff continued researching, the irony of (un)intentionality abounded. We learned that subsequent generations of the family also aimed to reform the prison, but often inadvertently accommodated it. Frances Seward, Miller’s daughter, was repulsed by the prison but covetous of the finely crafted furniture produced there. William Seward, who married into the family’s prison connections, advocated for reforms in prison education while also speaking about doing so “to secure the cheerful obedience of . . . the tenants of our state prisons.”[8] The pattern repeated itself across time. Auburnians, from the Seward family of the 19th century to family friend and industrialist Thomas Mott Osborne in the early 20th century, set themselves to reforming the prison believing their generation could rectify the mistakes of the past. Names and ideas changed; ACF has endured.

For staff, this concept emerged as the impetus for an exhibition nearly 18 months in the making. Starting with newly discovered ties between the family and the prison, we attached ourselves to the suggestive title, Rooted in Reform. Ultimately, SHM dedicated two adjoining former bedrooms to the exhibition, which we designed as a self-guided space for visitors to experience at the end of their guided tour. We built in time for optional dialogue with guides, trained volunteers in both carceral storytelling and diffusing tense conversations, and revised our interpretation.

The first room of the exhibition was designed as a warm, inviting, office—perhaps that of Judge Miller himself. This room introduces the show, includes a statement of intent from the museum, and centers around the historic importance of Auburn Prison as a site of reform and the Seward family’s direct connections to it. The space includes objects like Miller’s original law library, letters about the prison from William and Frances Seward, and discussion of the famous 1846 trial of William Freeman, in which Seward attempted to put the Auburn System on trial (fig. 4).[9]

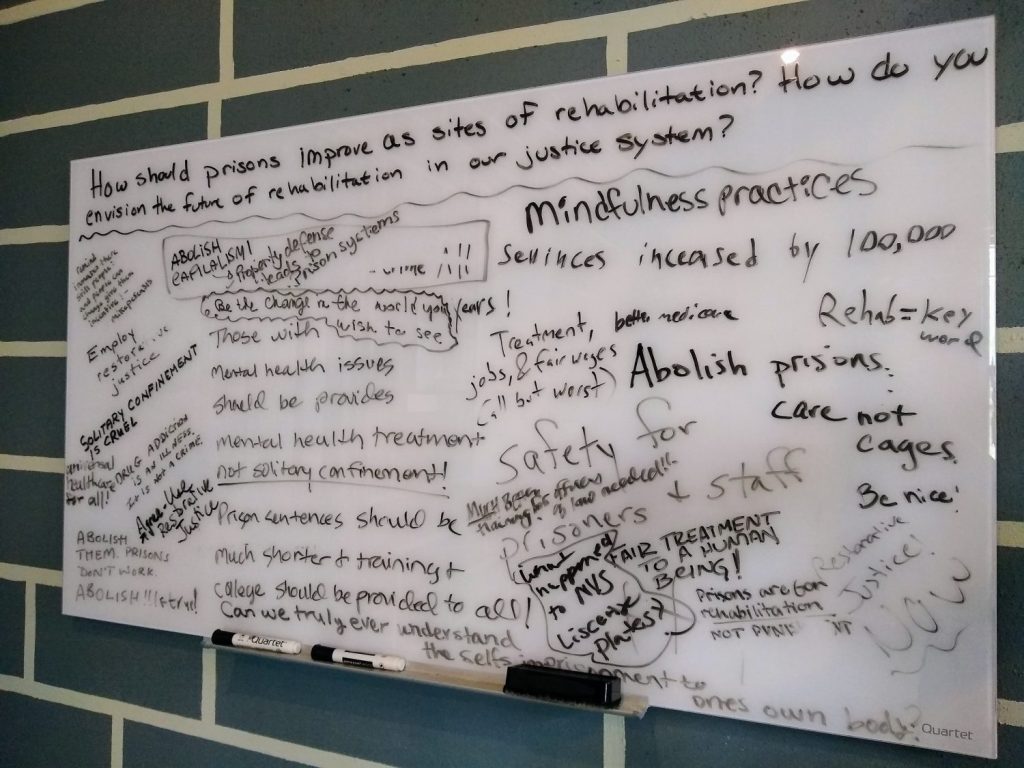

The second room serves as a juxtaposition, as visitors enter a cold and dreary cell within Auburn Prison (fig. 5). The design choice presents visitors with a jarringly stark spatial contrast and is meant to replicate harsh carceral realities. The installation was incredibly time consuming but its design has reaped praise in the visitor feedback we have received on a whiteboard, in comment cards, and online. On the other hand, some have questioned the potentially triggering nature of the design, though even these visitors frequently commented on the powerful, visceral experience. While the first room contextually stops before 1850, the second room takes a sweeping view of reforms within Auburn Prison from the late 19th century to the modern day. It includes a video clip of the 1929 uprising at ACF playing on a loop, as well as postcards and stereograph images of the prison.

The exhibition is not designed to be an exhaustive history or analysis of our carceral systems; rather it connects a historic family to a surprising legacy to inspire dialogue within the community. By grounding our exhibition in the core truth of the Sewards’ involvement with the prison, SHM was able to explore tougher subjects.

Challenges

The road to Rooted in Reform was lined with the sort of missteps and growing pains inherent in any process where museum staff must stretch themselves into new modes of interpretation and exhibition-making.

Finding Representation and Understanding

Going into Rooted, staff did not have an ideal depth of understanding or experience with carceral exhibitions. No one had worked in a prison museum or correctional facility, nor been formerly incarcerated. We had to confront bias, assumption, and a touch of guardedness from local staff at SHM, including members of the team with familial ties to the prison. Staff had to learn and adopt best practices for telling carceral stories with nuance and sensitivity, especially regarding terminology.[10] As we came to appreciate, common identifiers like “inmates” or “convicts” strip humanity from the people associated with them; instead, the preferred language is always “incarcerated people” or “formerly incarcerated people.” Even the state has followed this lexical lead: “prisons” are “correctional facilities,” “guards” are “corrections officers,” and “wardens” are “superintendents.”[11]

Re-educating ourselves on language was only the beginning. Staff also sought to cultivate relationships with new audiences that the museum rarely served in its normal operations—families within the corrections community as well as those of formerly and currently incarcerated people. These were critical voices to bring into the very fabric of the stories we wanted to tell, and we lacked not only basic relationships, but trust from within these sections of Auburn. We met with resistance from the internal partners we sought and needed more time to build reciprocal bonds. Over the last few years, this has happened, albeit slowly.

Differing Community Perspectives

Another challenge was the presence of differing community perspectives. Initially, even within our internal team, there was division. When gathering information and perspectives to include in the interpretation, staff found it difficult to create a narrative that met the satisfaction of all. What “stance” would the museum take when telling this story that some would deem “political”? Were we leaning in tone and verbiage toward the perspective of the correctional facility staff or the incarcerated people? Were we only “stating the facts” and remaining “neutral”?

In a prison town like Auburn, there was plenty of external pressure imposed by stakeholders and community members. The prison is a polarizing topic for our local audience, and in asking people to join us in turning their gaze toward the prison to ask hard questions and reconcile our two halves—History’s Hometown and Prison City—we provoked some defensive and emotional responses. We had to learn to leave room for heated conversations—within the exhibition and on the streets where we lived (fig. 6). For many Auburnians, the fact SHM broached this subject at all felt like unwanted active disruption from a house museum that should “mind its own business.” Putting the Sewards’ stories front and center allowed us to counter that carceral stories are our business. Moreover, in this country, the plight of mass incarceration is everyone’s business—and it is a story that begins in Auburn.

After interviewing various staff, volunteers, and community members, the panel-writing team concluded that neutrality was impossible but that causing major waves would take away the museum’s credibility and trust in the local community. In consultation with museum leadership, they decided that the answer to this challenge would be to focus content heavily on the prism of the Seward family’s connections to Auburn Prison and the legacy of circular reform that followed.

Time and Capacity

As is common for many small museums, time, space, and capacity were major hurdles when creating this exhibition. Originally, our schedule allowed only a matter of months for panel drafting and editing, installation, and object loaning and handling. While this may have been achievable had we spent years researching themes and cultivating relevant relationships, SHM was in new territory. Having only two former bedrooms to tell a broad story of prison reform was daunting, requiring constant strategic rethinking of our interpretive priorities. In the end, we added months to our opening deadline to give ourselves time to learn and adapt to a longer and more difficult process.

The Power of Partnerships

For all of its challenges, Rooted also opened up a world of possibilities that we never imagined. In the initial stages of learning how to engage in carceral storytelling, we sought help from experts, including the New York State Museum in Albany and leaders from the Association of Carceral Sites and Museums (ACSM), who provided guidance and invited us to join in their monthly discussion meetings.[12]

CANY

One partnership that has continued to evolve is that with the Correctional Association of New York (CANY).[13] CANY is an independent agency designated by New York law to provide independent monitoring and oversight of the state prison system. The organization traces its history back to the early 1840s, or around the time William Seward was Governor of New York. As archival research revealed, Seward had been a strong supporter of CANY. Indeed, not long after its founding, Seward was invited to address the organization at its annual meeting. Sending instead a letter of support, he heralded their work, announcing that he counted himself “a pupil of your own.”[14]

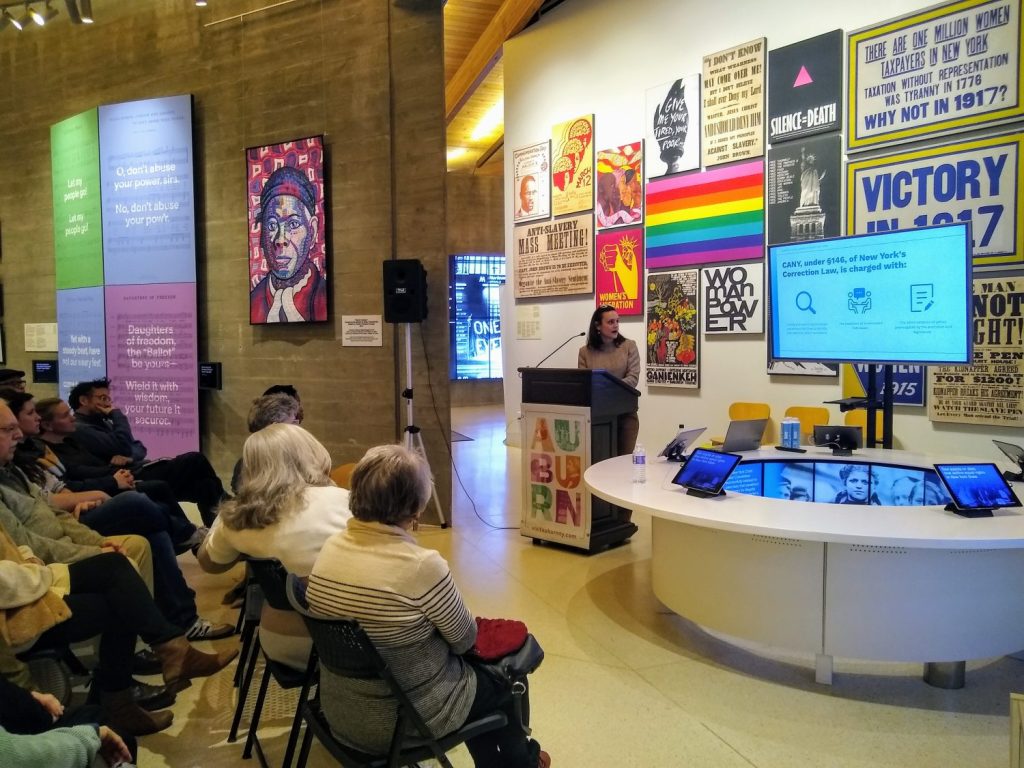

Building off of this initial intersection, SHM entered a mutually beneficial partnership with CANY. CANY helped us bridge many divides: providing access to modern prisons, entre into debates happening at the highest levels, and connections to the formerly incarcerated community. In turn, as CANY prepared for its 180th anniversary, SHM assisted in researching and telling its long organizational history, connecting its past to its current mission. A Post-Incarceration Humanities Partnership grant funded by Humanities New York has furthered the collaboration. As one main initiative of the grant, SHM assembled a team of local community members for a day spent inside ACF with CANY during a monitoring visit. The group of about 15 people brought together elected officials, faith and thought leaders, local business owners, other nonprofits, and educators, including the superintendent of schools. We spoke with prison administration, corrections officers, and incarcerated individuals while also spending time in cell blocks, medical and dental facilities, educational units, industrial facilities, and the yard—access that was both rare and incredibly powerful. With CANY, SHM is now leading a series of free community dialogue events about Auburn’s carceral landscape (fig. 7). A second monitoring visit is scheduled for later in 2024.

Educational Partnerships

Our work with CANY attracted the attention of regional universities that direct the prison education programs at Auburn. With faculty at Cornell University and the University of Rochester, we forged a new network of educational outreach and were introduced to new voices inside of the incarcerated and formerly incarcerated community.[15] In March 2024, SHM hosted Going Upstate, a traveling exhibition prepared by undergraduate and graduate students from the University of Rochester’s Education Justice Initiative. Placed in close proximity to and in conversation with Rooted, Going Upstate explored how carceral geographies like Auburn exist in liminal spaces that are “half social engineering and half illusions,” places of otherness that lend themselves to communal cognitive dissonance.[16] Through a montage-style pairing of prison objects with a series of images and firsthand stories of incarceration from ACF, the exhibition explored how the phrase “going upstate” became synonymous with mass imprisonment in New York.

When SHM opened for the 2024 season, so did Going Upstate. Whether due to the provocative nature of the combined storytelling, the dialogical aspect of the companion exhibitions, good timing, or a combination thereof, something remarkable happened for the first time since we launched Rooted: former correctional officers and formerly incarcerated individuals were in attendance together. SHM staff joined spontaneous conversations taking place in both exhibitions, feeling, at least for that moment, like the museum approached a third space ideal.

But ideals are fleeting and elusive, especially when it comes to disruptive, difficult storytelling. The opening day double reception has proven more high-water mark than consistent threshold for local engagement, and SHM still struggles to grow our connections with carceral communities.

Sharing Our Experience with the Museum Field

While the challenge of how to serve these audiences persists, SHM has sustained the momentum of Rooted in other ways, including sharing our experience integrating carceral stories into our organization with other small museums. SHM led two panels on the subject for the Museum Association of New York—pulling in the voices of our partners at ACSM, CANY, and the formerly incarcerated (fig. 8).[17] In 2024, we shared our story on a national stage with panels prepared for the AAM and AASLH annual conferences.[18] Regardless of the forum, SHM tries to represent not only small museums taking first steps, but to speak with humility and openness. These panels are not intended to be triumphal roadmaps celebrating success, but case studies reflecting our missteps and lessons learned.

Rooted in Retrospect

Rooted in Reform opened in May 2023 and remains open, at least until the end of 2024 (intro image). We would encourage other small museums to consider turning toward their own disruptive storytelling, even if they do not currently see a link to their mission. The investment we have made to build trust within different parts of the carceral community will allow the exhibition to be revised, incorporating a range of new voices and adding authentic interpretive layers it is currently lacking. The new sensitivities we have learned should improve the tone, and perhaps even the aesthetic choices, of Rooted.

Looking back, a few clear takeaways emerge:

- Plan on more time than even your most liberal estimates suggest you need; build time to foster staff alignment and open conversation

- Prepare for discomfort, internally and externally, as you approach difficult conversations in a polarized political climate; develop strategies for dialogue as well as de-escalation

- Connect your work to your mission—start from that specific entry point and expand outward into contested territory

- Seek partnerships and opportunities as broadly as you can; prepare to be humbled and cede ground to the expertise of others.

For any organization seeking to confront difficult history, methods matter as much as intention. Here in Auburn, in order to overcome the cycle of cognitive dissonance, we needed to accept that the history of ACF is all of our history—in the Seward House and beyond—and the future of the incarcerated and formerly incarcerated is also in our hands.

1 For a fuller accounting, see W. David Lewis, From Newgate to Dannemora: The Rise of the Penitentiary in New York, 1796–1848, illustrated ed. (New York: Cornell University Press, 2009).

2 See “Building a More Just Society,” Sing Sing Prison Museum, accessed May 23, 2024, https://www.singsingprisonmuseum.org/.

3 Benjamin F. Hall, “Genealogical and Biographical Sketch of the Late honorable Elijah Miller,” University of Rochester, River Campus Libraries, Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation, Elijah Miller Papers, box 6, folder 7, p. 74.

4 Scott W. Anderson, Auburn, New York: The Entrepreneur’s Frontier (New York: Syracuse University Press, 2015), 115.

5 “Solitary Confinement Should Be Banned in Most Cases, UN Expert Says,” The United Nations, accessed June 5, 2024, https://news.un.org/en/story/2011/10/392012.

6 Caleb Smith, ed., The Life and the Adventures of a Haunted Convict (New York: Random House, 2016), xlvii.

7 Specifically, almost all of the furniture provided for official state offices in New York is manufactured at ACF through Corcraft, the industrial wing of the New York State Department of Corrections and Community Supervision, which enjoys “preferred source” status for official state purchasing. The program has not been without its critics, including state senators. See, “Commentary: A Captive Market,” The New York State Senate, accessed June 5, 2024, https://www.nysenate.gov/newsroom/in-the-news/2023/zellnor-myrie/commentary-captive-market.

8 William Seward, “Abuses in the State Prison at Sing Sing” (Albany, New York: April 16, 1839). The full text of this report, prepared by Governor William Seward for the State Senate, can be found in George E. Baker, ed., The Works of William Seward, vol. 2 (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, and Co., 1888), 347–51.

9 An early and innovative use of the insanity defense, Seward argued that the traumatic violence rendered onto his client by the prison, including having a thick wooden board broken over his head, was responsible for permanent brain damage. Robin Bernstein, Freeman’s Challenge: The Murder that Shook America’s Original Prison for Profit (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2024). As Bernstein notes, “The blow [to Freeman] was so severe that board split lengthwise against the grain…the blow broke his ear drum, gave him a concussion, and damaged his left temporal bone” (48). Seward also called attention to the racial inequities inherent within criminal justice, demanding the all-white jury hold Freeman, of Afro-Native heritage, “to be a man” in “the image of our Maker” with no regard to “the color of the Prisoner’s skin.” Benjamin Hall, The Trial of William Freeman for the Murder of John G. Van Nest (Auburn, New York: Derby, Miller, & Co., 1848), 374.

10 Fortunately, staff from a number of carceral sites and organizations came to SHM’s aid and offered guidance. In addition to staff from the Sing Sing Prison Museum, SHM benefitted from the support of leadership from Eastern State Penitentiary, Alcatraz, and many others in this educational process.

11 “What Words We Use—and Avoid—When Covering People and Incarceration,” The Marshall Project, accessed March 2, 2024, https://www.themarshallproject.org/2021/04/12/what-words-we-use-and-avoid-when-covering-people-and-incarceration.

12 For more on the ACSM, see Association of Carceral Sites and Museums, accessed May 23, 2024, https://carceral.org/.

13 For more on CANY, see “Independent Prison Oversight Since 1844,” CANY, accessed May 23, 2024, https://www.correctionalassociation.org/.

14 The complete archival history of CANY has been deposited at SUNY Albany and much has been digitized. For Seward’s letter, sent 14 December 1846, see “Third Report of the Prison Association of New York,” University at Albany State University of New York, M.E. Grenander Special Collections and Archives, Correctional Association of New York Records, 1844–1988, reel 1, p. 18.

15 For Cornell’s Prison Education Program, see “Overview,” Cornell Prison Education Program, accessed May 23, 2023, https://experience.cornell.edu/opportunities/cornell-prison-education-program; for the University of Rochester’s Education Justice Initiative, see “Rochester Education Justice Initiative,” School of Arts & Sciences, accessed May 23, 2024, https://www.sas.rochester.edu/reji/.

16 For more on Going Upstate, including its gallery guide, see GOING UPSTATE AUBURN, NY, accessed June 5, 2024, https://goingupstate.org/index.php/2024/03/01/going-upstate-auburn-new-york/.

17 The MANY panel, “Prison Prisms,” was reprised as a virtual offering following its success at the 2023 annual conference. For more, see “Prison Prisms: Reflections on Prison History and Criminal Justice Reform in NYS through the Lens of Auburn, Attica, and Sing Sing,” Museum Association of New York, accessed, May 23, 2024, https://nysmuseums.org/Prison-Prisms.

18 For more on the American Alliance of Museum’s 2024 Conference, see: https://annualmeeting.aam-us.org/; for the American Association of State and Local History’s 2024 Conference, see: https://www.aaslh.org/annualconference/2024-annual-conference/.