Digital information is inherently far more ephemeral than paper.

—Natalie Ceeny, CEO, National Archives (UK)

This article originally appeared in Museum magazine’s January/February 2025 issue, a benefit of AAM membership.

The world’s first website was published on August 6, 1991, and by 2004, 88 percent of museums reported having a site. Social media began its explosive growth in the early 2000s—fast forward two decades, and one museum alone, the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, has over 13.3 million followers on the major social platforms. Now it’s hard to imagine operating a cultural nonprofit, managing collections, or interfacing with the public without digital tools and platforms. Customer relationship management (CRM) software is integral to managing communications, membership, and donor relations. Museums use artificial intelligence for business analytics, for attendance projections, and to establish variable pricing for tickets.

But along with power, scale, reach, and almost magical abilities, the digital era brings new challenges. What risks are posed by our current reliance on digital storage, platforms, and tools? How can museums recognize and mitigate these vulnerabilities?

The Challenge

The internet is so integral to the functioning of society that, in 2021, the United Nations declared internet access to be a basic human right. But despite, or perhaps because of their power, speed, reach and complexity, the digital systems on which we have come to depend are also increasingly vulnerable to disruption.

Some of these weaknesses are due to what conservators call inherent vice—fundamental instability, whether due to data degradation (aka bit rot) or the decay of storage media. The rapid rate of technological evolution may render even stable data unreadable by future hardware and software. And even good, readable data may become unfindable: a 2024 study found that two thirds of links in websites created in the last nine years are already dead (a phenomenon dubbed, of course, link rot). Also in 2024, the Pew Research Center found that a quarter of all web pages that existed between 2013 and 2023 are no longer accessible.

Sometimes data is “lost” on purpose, as when 25 years of music journalism disappeared after Paramount took the MTV News archive offline last June. Sometimes it goes missing by accident, as in 2019 when MySpace erased almost everything uploaded before 2016 in a data migration gone horribly wrong. Sometimes data is a victim of precarious business models: when Vice went bankrupt in 2024, journalists scrambled to download their articles and save links to public archives before the publication’s website went dark. With increasing frequency, data loss is malicious: cybersecurity firm Black Kite reported an 81 percent increase in ransomware attacks between 2023 and 2024, translating to nearly 5,000 incidents worldwide, which in the US resulted in significant disruptions to universities, hospitals, and government agencies.

Because our digital systems are massively integrated, such damage can be widespread. In July 2024, 8.5 million devices running Microsoft Windows were crippled by a faulty software update distributed by the cybersecurity company CrowdStrike. The crash grounded over 5,000 commercial flights and led hospitals to postpone procedures and cancel non-emergency services. As scholar Nassim Taleb points out, such outages are an inherent property of fragile, complex systems that accumulate hidden risk. These risks are amplified by the fact that digital infrastructure is inextricably intertwined with another aging, underfunded system—the US power grid—that with increasing frequency suffers local collapse during extreme weather.

The fragility of digital data and digital systems poses a threat not only to our day-to-day functioning but to our heritage and history. The National Archives cares for over 13.5 billion pieces of paper, 41 million photographs, and more than 450 million feet of film. Yet the size of these holdings is dwarfed by the 402 terabytes of digital data that 8.2 billion humans generate every day. That amounted to 147 zettabytes in 2024 alone, with a zettabyte consisting of 2 to the 70th power bytes (bytes being the basic unit of digital storage). For scale: one zettabyte has been compared to “as much information as there are grains of sand on all the world’s beaches.” Previously, much of the information humanity generated was never captured at all, and of the information embodied in physical form, only a portion survived. But as internet pioneer Vint Cerf has pointed out, with so much information—correspondence, images, business records—going straight to digital, a massive failure in shared systems could lead to what he has dubbed a “digital dark age.”

What This Means for Museums

The vulnerabilities outlined are critically important for museums—organizations that often center preservation in their missions and increasingly depend on digital to maximize reach, impact, and income.

Conservators and collections management staff have spent countless hours learning how to stabilize physical objects and mitigate physical risks. Even with that knowledge, our sector has long faced severe limitations (time, money, training) in applying what we know. In 2005, the Heritage Health index reported that of the 4.8 billion objects collectively cared for by cultural institutions, up to half were in need of conservation, and 40 percent were in “unknown condition.” As of 2024, only 69 percent of museums reported having emergency response plans—and those plans largely address historic, analog risks such as earthquakes, floods, and fire. (The true figure is probably even lower, as small museums tend to be underrepresented in such survey data.)

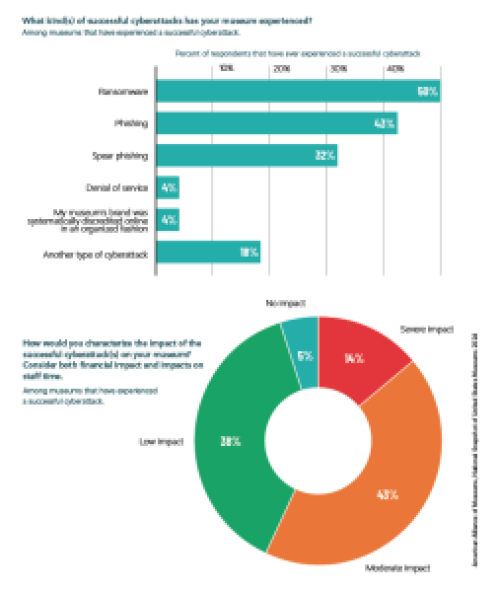

Yet museums are just as susceptible to digital risk as airlines, banks, and hospitals. A growing number of museums have fallen prey to successful cyberattacks either directly or through their service providers. In January 2024, a Russian cyber group launched a ransomware attack on Gallery Systems, shutting down the eMuseum platform used by hundreds of museums to provide access to online collections and in some cases the TMS program used for collections management. Many museums were impacted by the CrowdStrike outage, particularly those in government or university systems. Some delayed opening, as they scrambled to put together paper-based systems for ticketing and sales; others decided to let visitors in for free. In one case, the HVAC system for a museum data storage center was affected, leading temperatures to soar and putting that data at risk.

In addition to the overt hazards of cybercrime and fragile systems, many museums are exposed to a subtler risk: that of overdependence on “free” digital platforms and services. Instagram, X, Facebook, TikTok, and YouTube give even tiny organizations the ability to cultivate an international following, and they have become critical marketing and PR strategies tools for museums large and small. But the corporations that control these platforms can and do change their terms of service, tweak their algorithms, or alter their content moderation in ways that minimize museums’ audience or block their content. After making huge investments in experimental services, big tech companies may abandon whole systems if they don’t pay off. (Some pundits warn that generative AI, having sucked up over $1 trillion in development costs so far, may be just such a bubble waiting to pop.) Entire countries may lose access to platforms as governments crack down on social media to suppress free speech or control espionage and foreign manipulation.

If “free” access to commercial social media platforms is a fragile strategy, what are the alternatives? A small but growing number of nonprofit, collaborative, open-access systems replicate the general structure of for-profit systems, though they often don’t (yet) offer the same reach and scale. One option is to create and share content via a common protocol like ActivityPub, which ensures creators (individuals or organizations) own and control their data. That data can then be channeled into “federated” apps like Mastodon (an X alternative), Pixelfed (like Instagram), PeerTube, and Friendica (with the obvious equivalents). Even Meta is getting in the game, integrating its recently launched Instagram microblogging feature, Threads, into the “fediverse” of apps that use common protocols.

In addition to the digital concerns faced by any type of organization, many museums have additional challenges tied to their mission of preservation. Where a collections catalogue record might once have consisted of an entry in a logbook, a card in a drawer, a file (however fat) of paper documentation, and maybe some prints and negatives, digital records may include all that information plus 3-D scans, links to related records in other museums’ databases, multiple versions of edited files, and digital copies of stories, images, and annotations contributed by the public. Increasingly, museums are collecting born-digital content as well, including emails, manuscripts, works of art, scientific data, computer programs, and games, as core to their collections.

As SFO Museum’s Aaron Straub Cope has pointed out, nearly every museum, large or small, relies on one of the big three cloud providers (Amazon, Microsoft, or Google) for storage and retention of these digital assets. While any one of these companies may be “too big to fail,” and by extension a “safe bet,” the sector is nonetheless dependent on external vendors to fulfill its mandate.

Being good digital stewards requires staff who can help the museum create resilient, “antifragile” systems in addition to planning for risk management and emergency response; training staff in good digital hygiene; and funds for digital preservation, including monitoring the condition of digital data and migrating as needed to new platforms and formats. (See the “Digital Depreciation” sidebar at left.) AAM’s historic data shows that, as of 2009, museums were devoting a median 8 percent of their operating expenses to collections care. Per the quote from Natalie Ceeny that opened this article, digital data is inherently more ephemeral than paper … or wood, stone, ceramic, or metal. In the future, the costs of digital preservation could easily outstrip the traditional costs for archival materials, HVAC, and security needed to stabilize physical collections.

If Vint Cerf is right, and the world does face a digital dark age, how can museums help preserve culture and heritage? As collecting institutions, they will play a role in choosing what gets preserved. Being all too aware of how past choices marginalized and silenced some histories, museums will hopefully take a broad-minded and equitable approach to the preservation of shared digital heritage. Whatever they deem worthy of saving, museums will have to be as mindful of how they store data, detect and repair errors, protect it from accidental or malicious destruction, and ensure it remains readable in decades or centuries to come.

Sidebars

Museums Might …

- Maintain an inventory of all digital platforms the museum uses, along with a record of login credentials and passwords, to ensure that access, and data, are not lost due to staff turnover. Many platforms are tied to individual accounts, so museums will need to include steps for adding and deleting account managers in their offboarding procedures.

- Per scholar Nassim Taleb’s recommendations, create “antifragile” digital systems by avoiding overuse of a single platform, decentralizing systems, building in excess capacity and redundancy, and engaging in continuous learning around failures and weakness. And, of course, institute regular data backups!

- Provide mandatory staff training on cybersecurity.

- Create an emergency response plan for coping with successful cyberattacks, including policy decisions (e.g., paying ransom), communications, pre-identified contractors to use in recovering data or systems, and procedures for operating in absence of digital systems.

- Rethink the common “everywhere at once” marketing mentality, and focus on critical, stable platforms that achieve the museum’s goals for marketing and communications. Resist the temptation to be on every free platform and use every new free tool.

- Cultivate a healthy digital skepticism. New digital tools often get a lot of press because of the marketing dollars invested in their launch. Hot new things may not last, or may quickly convert to a fee-for-service model the museum cannot afford.

- Review or create policies and procedures for archiving museum data that is of lasting interest or value.

- Create a realistic definition of digital preservation that reflects an institution’s resources and capabilities. Approach preservation with a “something is better than nothing” mind-set. What materials are being collected and preserved by other organizations, and what is your museum uniquely positioned to care for?

Digital Depreciation

Depreciation (dih-pree-shee-ey-shuhn), noun: any decrease in the value of property (as machinery) for the purpose of taxation that cannot be offset by current repairs and is carried on company books as a yearly charge amortizing the original cost over the useful life of the property. Source: Merriam-Webster.

When a company makes a big investment in a tangible, physical asset—like a roof, an HVAC system, or a vehicle—it books these expenses in a way that spreads out the cost over the useful life of that asset. Setting aside the tax advantages (which may be irrelevant to nonprofit museums), this accounting practice, known as depreciation, helps ensure that a museum sets aside the funds needed to replace these assets at the end of their projected life span.

The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), which issues the standards that guide the audits of all companies, including nonprofits, considers the physical equipment that captures and stores data—computers, hard drives, scanners—depreciable, but not the data itself. However, this author (that is, Elizabeth Merritt, Director of CFM) would like to argue for a parallel approach to projecting and planning for the costs of preserving digital data over time.

Museum digitization projects are often made possible by funders who like the idea of using new technology to make museum content “digitally accessible to the world.” Funding the maintenance of data sets is, frankly, less appealing and may well hinge on proof that the resulting digital data is actually used. The iDigBio project, based at the Florida Museum of Natural History, has amassed ~143 million specimen records and ~57 million images from about 350 US institutions. The National Science Foundation has invested over $100 million in iDigBio and its partners, a success fueled in large part by extensive training efforts (including webinars, workshops and symposia) that help the project reach over 25,000 users per month.

This project, huge as it is, represents only a fraction of the digitized collections data US museums hold. In coming decades, how much will it cost to detect and repair bit rot? Monitor and archive orphaned websites and data sets? Migrate millions of digital files into formats and storage media that continue to be accessible as technology evolves? In the future, calculating and budgeting for such costs will be just as critical as planning to replace the museum’s roof, the HVAC system, or the bus that carries traveling exhibitions across the state.

So here is a new entry for the museum lexicon:

Digital depreciation: the process of calculating and budgeting for future costs of maintaining a museum’s digital records (including digital collections and digital documentation of analog collections) in a stable, readable, accessible format over the long term.

Museum Examples

In 2023, the Pérez Art Museum Miami launched its own free streaming service, PAMMTV, presenting works from the museum’s collection of art and video films. By creating its own platform, rather than using a commercial site such as YouTube, the museum insulates itself from the policies and control of such platforms. It also means the museum can assure artists they will have control over their content, as well as ensure that users’ data is not harvested for use by third parties.

In 2023, the Pérez Art Museum Miami launched its own free streaming service, PAMMTV, presenting works from the museum’s collection of art and video films. By creating its own platform, rather than using a commercial site such as YouTube, the museum insulates itself from the policies and control of such platforms. It also means the museum can assure artists they will have control over their content, as well as ensure that users’ data is not harvested for use by third parties.

The Corning Museum of Glass (CMoG) has developed a “defense in layers” approach to mitigate IT and digital environment risks, increase operational efficiency, and enhance access to collections. The museum deploys a balance of on-site systems and cloud services to support its mission while managing risk and safeguarding the collections. This strategy uses people, policy, and systems to strengthen disaster recovery along with comprehensive protocols that ensure digital preparedness, information security, and digital incident response. CMoG’s Information Security Awareness Program reinforces best practices, training, and vigilance for its most vital resource: the museum workforce. A steady rhythm of annual training, phishing simulations, and information fosters a culture of awareness among staff that reinforces everyone’s role in protecting digital resources. With this awareness, and thorough guidance for identifying and remediating digital incidents that arise, the museum is confident that it can effectively manage disaster recovery, safeguard collections, and foster trust in an unpredictable world.

The Corning Museum of Glass (CMoG) has developed a “defense in layers” approach to mitigate IT and digital environment risks, increase operational efficiency, and enhance access to collections. The museum deploys a balance of on-site systems and cloud services to support its mission while managing risk and safeguarding the collections. This strategy uses people, policy, and systems to strengthen disaster recovery along with comprehensive protocols that ensure digital preparedness, information security, and digital incident response. CMoG’s Information Security Awareness Program reinforces best practices, training, and vigilance for its most vital resource: the museum workforce. A steady rhythm of annual training, phishing simulations, and information fosters a culture of awareness among staff that reinforces everyone’s role in protecting digital resources. With this awareness, and thorough guidance for identifying and remediating digital incidents that arise, the museum is confident that it can effectively manage disaster recovery, safeguard collections, and foster trust in an unpredictable world.

In 2024, the SFO Museum at the San Francisco International Airport joined the fediverse by creating a series of automated “bot” accounts that are published (broadcast) using the ActivityPub protocols and can be subscribed to from any client that supports those standards (including Meta’s Threads application). The project launched with three “groups” of accounts: things that have happened recently involving the SFO Museum aviation collection, things that have happened in the terminals (new and old), and things from the collection that are related to flights in and out of SFO. Staff have also set up accounts for the individual SFO terminals, past and present, that will publish installation photos of the over 40 years’ worth of exhibitions they have housed. This project establishes a social media presence that the museum controls, capitalizing on the reach of commercial social media while inuring itself against corporate decisions that may adversely affect the museum’s ability to reach its audiences, or may be at odds with the goals and values of the airport or the city of San Francisco.

In 2024, the SFO Museum at the San Francisco International Airport joined the fediverse by creating a series of automated “bot” accounts that are published (broadcast) using the ActivityPub protocols and can be subscribed to from any client that supports those standards (including Meta’s Threads application). The project launched with three “groups” of accounts: things that have happened recently involving the SFO Museum aviation collection, things that have happened in the terminals (new and old), and things from the collection that are related to flights in and out of SFO. Staff have also set up accounts for the individual SFO terminals, past and present, that will publish installation photos of the over 40 years’ worth of exhibitions they have housed. This project establishes a social media presence that the museum controls, capitalizing on the reach of commercial social media while inuring itself against corporate decisions that may adversely affect the museum’s ability to reach its audiences, or may be at odds with the goals and values of the airport or the city of San Francisco.

Resources

Cyber Essentials Toolkit, America’s Cyber Defense Agency, 2020

This toolkit consists of modules designed to break down the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency’s cyber essentials into bite-sized actions for IT and C-suite leadership. It includes recommended actions to build an organizational culture of cyber readiness.

cisa.gov/resources-tools/resources/cyber-essentials-toolkits

Wendy Pryor, “Safety First: How Museums Can Embrace Cyber-Security Opportunities and Risks with Open Arms,” Museum, May/June 2018

aam-us.org/2018/05/01/safety-first-how-museums-can-embrace-cyber-security-opportunities-and-risks-with-open-arms

IndieWeb

This people-focused alternative to the “corporate web” provides step-by-step instructions for implementing a Post (on your) Own Site, Syndicate Elsewhere (POSSE) approach to social media. This practice consists of posting content on your own site first, then publishing copies or sharing links to third parties (like social media silos) with original post links to provide viewers a path to directly interacting with your content.

indieweb.org/POSSE

Comments