The Home of Franklin D. Roosevelt National Historic Site now has a disability-affirming interpretation of FDR’s life after polio.

This article originally appeared in Museum magazine’s March/April 2025 issue, a benefit of AAM membership.

“After all, what is the difference, what does it matter if you or I walk with a limp or have something wrong with an arm—that is a small thing in any life.”

—Franklin Delano Roosevelt, radio address, February 18, 1931

In recent years, museums and historic sites have increasingly focused on accessibility. However, accessibility is much more than physical accommodation; it’s about creating spaces where people with disabilities feel genuinely included and valued.

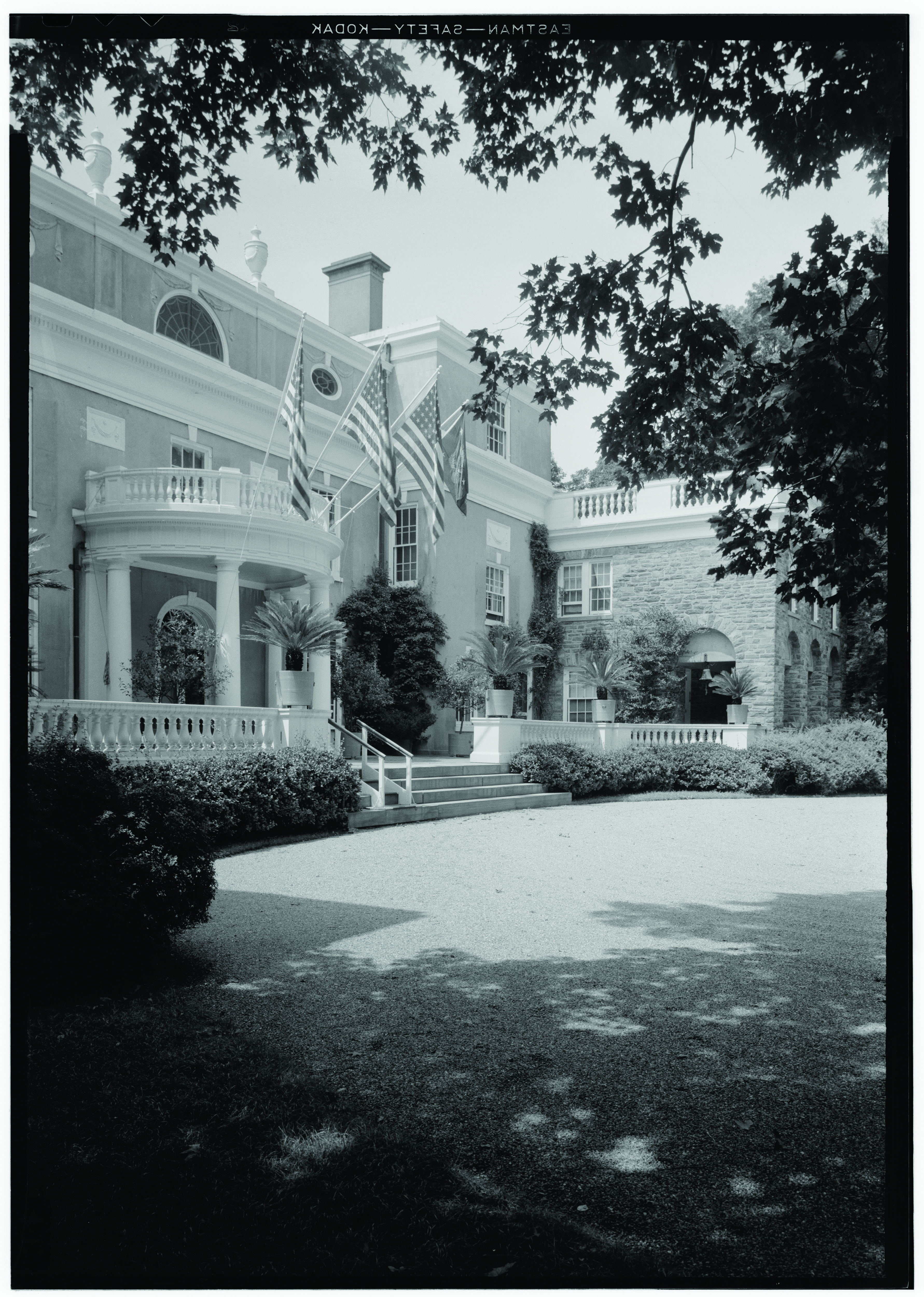

Many National Park Service (NPS) sites have important disability stories, but the Home of Franklin D. Roosevelt National Historic Site (Home of FDR) has the strongest one that is central to its interpretive programming. In 2023, under the leadership of Curator Frank Futral, the Home of FDR received funding that has allowed me to serve in a fellowship focused on disability representation at historic sites. I work closely with the curatorial and interpretive divisions at the Home of FDR as well as with the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library.

In the first year of my fellowship—observing tours, evaluating our website content, reading biographies, and diving into the archival collections—we realized there is a great irony in how we remember FDR, and most people get it wrong. Through this research, we discovered a significant gap in how FDR’s disability story is remembered, prompting us to reframe the narrative.

A History-Challenging Exhibition

FDR was one of thousands of Americans infected with the poliomyelitis virus in 1921 at the age of 39. At first, he experienced almost total paralysis from the neck down, but through physical therapy, exercise, and the best medical care available at the time, he recovered much of his muscle function. However, he would remain partially paralyzed in his lower legs for the rest of his life.

Following his recovery from the infection, FDR spent a lot of time learning how to use various mobility aids—such as crutches, canes, leg braces, and customized ramps, handrails, wheelchairs, and automobiles—which he relied on throughout his public and private life.

While FDR is one of the most recognizably disabled historical figures, his disability is commonly represented in ways that imply he hid the truth of his paralysis from the public. Historians and biographers regularly highlight the few surviving photos of FDR in a wheelchair as proof of this, overlooking the visible presence of other mobility aids he regularly used.

Though he became disabled before the height of his political career, many people telling his story imply he must have hidden his paralysis because the American public would never have knowingly elected a disabled person to a state governorship, much less to the presidency. My research has revealed the opposite. Not only did FDR openly discuss his disability in speeches and radio addresses, but mobility aids are visible in almost every photograph and film reel taken of him. Primary source evidence such as newspaper articles, photographs, and archival materials allow us to state for a fact that FDR’s paralysis and use of mobility aids was observed and discussed by many, including the president himself.

The NPS is reframing the narrative on FDR’s disability in a new exhibition—“First Things First: FDR, Disability, & Access”—that reexamines how FDR navigated public perceptions of disability, offering new insights into his impact on attitudes toward disability. The exhibition, opening in May 2025, features never-before-published images of FDR using his mobility aids as well as diagrams used in the construction of these devices unearthed from the Secret Service archival files at the FDR Presidential Library. We will also display a pair of his shoes that were customized to be connected to leg braces, a couple of his canes, and our pièce de résistance, a scaled, tactile model of one of FDR’s customized wheelchairs. With these images and objects that highlight not only his disability but also the very public nature of it, we hope visitors will have a more complete and nuanced understanding of FDR’s disability.

While the exhibition content is groundbreaking, equal care was taken to ensure its design meets the highest standards of accessibility. While accessibility is legally mandated for sites that receive federal funding, it is not always consistently implemented. It can be hard to get right, and best practices are always evolving.

We collaborated with accessibility experts from the Harpers Ferry Center (the NPS’s media development center) and the Institute for Human Centered Design. Both work with disabled-user experts to test exhibit spaces and content. They have guided us through color contrasting, font types, and eye-level zones on the wall panels; approachably sized images on the reader rails; cane detectability; knee and toe clearance; principles of plain language; audio description; and more.

In His Own Words

We hope that by taking all of this into consideration, disabled visitors will feel welcome and prioritized. However, for this to occur, we needed to do more than make sure everyone could access and engage with the space and content. We wanted the content to tell FDR’s disability story in an affirming way. To do so, we looked to FDR’s own words.

Evidence shows FDR was not ashamed of his paralysis and use of mobility aids. He talked about it matter-of-factly, encouraging others to treat him with respect and dignity—a novel perspective in an era when people with disabilities were regularly institutionalized and treated as “invalids,” a word commonly attributed to anyone with a disability at the time. He was compelled to dispel the limiting beliefs about people with disabilities to convince the public that he was capable of serving in office.

For example, in 1924, at his first large-scale public appearance after becoming paralyzed, the Chicago Tribune wrote that FDR was “hopelessly an invalid, his legs paralyzed. Wheel chair, crutches, and attendants are with him wherever he goes.” This language would continue throughout his career. In 1929, FDR was called a “victim of a wheel chair and steel braces” by a North Carolina newspaper.

FDR was aware of this stigma, which he made clear in a letter he sent to someone who was in the audience at a political meeting in Madison Square Garden in 1925. During a tribute to President Coolidge and again during the national anthem, FDR remained seated. The audience member wrote to him to criticize what he viewed as disrespect, and FDR replied as follows.

As I wear steel braces on both legs and use crutches it is impossible for me to rise or sit down without the help of two people. After presiding at the opening of the meeting and turning it over to Bishop Manning I returned to my seat, sat down and remained seated during the rest of the evening. It is, of course, not exactly pleasant for me to have to remain seated during the playing of the National Anthem and on other occasions when the audiences rise, but I am presented with the alternative of doing that or of not taking part in any community enterprises whatsoever.

This is just one of many examples of how FDR combated the public’s negative views and limited understanding of disability. FDR publicly and strategically discussed his disability by framing it as inconsequential to his ability to serve in office. In a speech he gave at Jamestown, New York, in 1928, he made this distinction with his usual tongue-in-cheek tone.

Do I look to you good people like an unfortunate, suffering, dragooned candidate? We started—the Democratic State Ticket and I started, day before yesterday, from Jersey City, and since then, commencing with Orange County, we have spoken in every single county along the Southern tier. That is pretty good for an unfortunate invalid and a lot of other cripples. … We left Elmira this morning by motor, and we have had six outdoor meetings today. So I hope you will pardon me if my voice is a little bit frayed tonight. That is the only part of me, except a couple of weak knees, physically, but not morally.

Because many people equated disability with ill health or invalidism, FDR emphasized his good health and vigor by frequently recounting his extensive travels and foregoing the use of a wheelchair that may have caused audience members to incorrectly assume he was an “unfortunate invalid.”

In 1929, FDR was interviewed by a journalist about the residents at Warm Springs—the first-of-its-kind polio rehabilitation center that he established—and disabled people at large.

Legs and arms, feet and hands! Mere appendages, that’s all. We don’t think with them or keep alive with them. … These leg or arm or foot or hand people are not invalids. Their bodies are well, generally above the average.

Again, he is making a point to distinguish people who are disabled—in this case, physically disabled—from people who are “helpless,” victims, or unhealthy. He likely made these rhetorical distinctions due to periodic “whisper campaigns” that suggested he was unfit for office. FDR and his advisors were compelled to address these concerns frequently and fervently, again supporting our contention that his disability was not intentionally kept out of the public sphere.

This exhibition will be the first time the Home of FDR National Historic Site uses FDR’s own words to talk about his disability. We mirror his matter-of-fact approach in our interpretation as well. Though we can only speculate about FDR’s personal feelings about his disability, we can acknowledge that the hidden disability narrative is more nuanced than is sometimes told, and our exhibition will provide several examples of explicit, public reference to FDR’s disability during his lifetime.

Sidebars

Person-First Language

The words we use to talk about disability are constantly evolving. In FDR’s lifetime, terms like “crippled,” “handicapped,” and “invalid” were commonplace. Today, most people either use person-first or identity-first language. Person-first language, such as “person with a disability,” emphasizes the individual over the disability. Advocates for this approach believe it helps shift focus away from the impairment, reducing stigma.

However, person-first language is not universally accepted. An example of identity-first language is “disabled person.” Identity-first language is often preferred by deaf, autistic, and other disabled self-advocates. They view disability as a positive and essential part of—rather than separate from—their identity. At the Home of Franklin D. Roosevelt National Historic Site, a combination of outdated terms, person-first language, and identity-first language is used. This approach reflects the historical context of FDR’s words while acknowledging shifting perspectives on disability terminology.

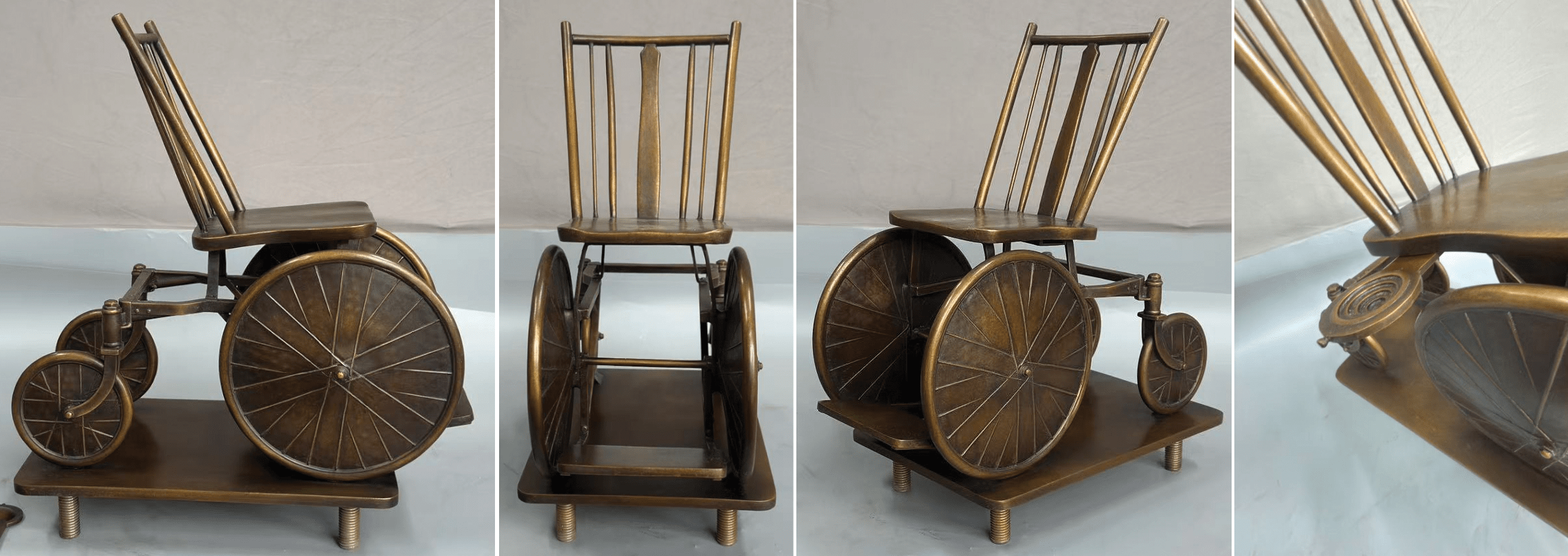

Tactile Model

This scaled, tactile model of one of FDR’s customized wheelchairs will offer visitors a comprehensive understanding of its unique design (including its retractable ashtray). We wanted to highlight the innovation of FDR’s unusual design and realized visually impaired visitors may not be able to see the photographs on the wall panels, nor would an audio description provide the full experience. At first, we tried a bas relief design, but guidance from user-experts ultimately led us to choose a roughly 18-inch tall, 3-D model that visitors could wrap their hands around. As with all universal design principles, this 3-D model will also offer sighted visitors a more dynamic experience.

A Commitment to Disability Inclusivity

The National Park Service (NPS) is committed to inclusivity, and many parks have improved access to their visitor centers, historic house museums, and even their campsites and trails. More than elevators, ramps, braille, and plain language writing, the NPS also has several agency-wide and site-specific initiatives to improve disability inclusivity, including the Telling All Americans’ Stories Disability History Series and the Mellon Humanities Postdoctoral Fellowship. These programs aim to improve how the NPS tells the sometimes complicated and controversial stories about disability in ways that minimize harm to disabled visitors.

This is absolutely fascinating and brings back memories for me. My masters thesis was on access in historic ships, and one of the ships I talked about was the Potomac, FDR’s yacht. I used it as an example of a ship that had built in modifications that other historic ships could emulate, like the elevator shaft disguised as a smokestack, wider hatches, and lower thresholds. Thank you for doing this exhibit and highlighting a misunderstood and little-known aspect of FDR. I hope I can get out there to see it.

I love this! Thank you and to the team at ROVA! Nice job