Museums have power—the power to tell stories, shape narratives, and influence the lens we bring to bear on the past. That power can be harnessed for healing, as museums contribute to a reparative reexamination of history and the legacy of historic injustice. TrendsWatch 2019 highlights how some museums are using their power to decolonize our culture, our country, and their own organizational practice. Today on the Blog, Christine Lashaw tells us how she and her colleagues at the Oakland Museum of California have collaborated with the museum’s Native Advisory Council to tell hard truths about the state’s history.

–Elizabeth Merritt, VP Strategic Foresight and Founding Director, Center for the Future of Museums

At the Oakland Museum of California (OMCA), we strive to present the past in a way that helps us understand the present, often surfacing multiple points of view. Our Gallery of California History is organized around the theme “Coming to California,” with an emphasis on sharing stories of immigration, settlement, and other social struggles. Inside the gallery’s “Coming for Land (1850-1915)” section, which presents the perspectives of the varied groups of people who struggled to control land and the wealth it brought, we’ve opened a new subsection called “Taking Native Lands and Lives.”

The goal of this installation, which opened in September of 2018, is to illuminate the genocide of Native peoples in California between 1848 and 1870, just after the Gold Rush. During this period, the Native population plunged from roughly 150 thousand to 30 thousand. This rapid decline was due mostly to blatantly racist policies and actions: White settlers wanted land they considered theirs for the taking and justified atrocities against Native people in pursuit of those ambitions.

How does an institution tackle this history that has for too long been missing from general scholarship, state education curricula, and even our own museum? The answer: very thoughtfully and in collaboration with Native peoples.

To begin, I’ll describe the installation, “Taking Native Lives and Lands”, which is organized into three parts. The first, “Broken Promises,” includes an 1830s land-surveying tool, a map of “public lands” from 1859, and an unratified treaty that negotiated land agreements between the U.S. government and California Native people. These objects illuminate the truth about the ways in which the U.S. government set Native people up to have no legal claim to land and to be vulnerable to violence.

The following section, “Exterminate Them,” unpacks the deliberate and violent campaign against California’s Native people. Through massacres, forced labor, and removal from their lands, Native people experienced genocide. It was difficult to find objects to tell this story. We relied on some photographs from the era and one powerful artifact from our collection: a California State Bond for War Indebtedness. I was appalled to learn that this bond was actually sold to white settlers to fund attacks against Native people.

The final section may in fact be the most important one—it certainly is for our Native advisors. “Revitalization and Activism” makes it clear that the genocide ultimately failed because of the resilience and strength of California’s Native people. Three powerful and colorful photographs of contemporary Native people show that Native and non-Native people alike are urgently working to revitalize traditions and fight for natural resources, control of land, and sovereignty.

Imbue Objects with New Meaning

In designing this installation, our team wanted to create a space that supported the emotional intensity of the topic. To do this, we played with color, lighting, and the juxtaposition of objects, images, and words. In the center of the space is a dramatically lit case filled with guns from the time period. Wrapped around the case is a quote:

“Before daylight the village was attacked by white men with guns and axes. Most of the women and children were killed, and the houses burned. I was one year old. My mother was killed, and when I was picked up….I was covered with my mother’s blood.”

The guns point toward the back wall at a map showing the locations of massacres in California from 1849 to 1873, and is flanked on either side with a portrait and a personal survival story. These tales are horrific.

This new way of displaying guns from our collection is critical to the experience and represents a deliberate shift in strategy. It transforms them from banal emotionless artifacts to objects that carry the weight of the violent acts they were used to commit. It is impossible to view the guns without first encountering the quote (above) that describes a personal tragedy. Equally powerful is how you feel when you stand at the end of the case and see the barrels of multiple guns pointed directly at you. I have even had some staff members tell me that it’s so uncomfortable and brings up so much fear that they are unable to stand there. We did not anticipate this effect, but the gun installation certainly elicits a strong emotional response.

Uplift Non-dominant Narratives

Dominant narratives describe westward expansion of white settlers as progress; they promote Manifest Destiny—the notion that white settlers were destined to occupy all of North America. At OMCA, we feel we have a responsibility to shift this narrative and foreground the impact white settlement had on Native peoples. In California, this history amounts to nothing less than genocide, comprised of massacres, forced labor, and forced removal.

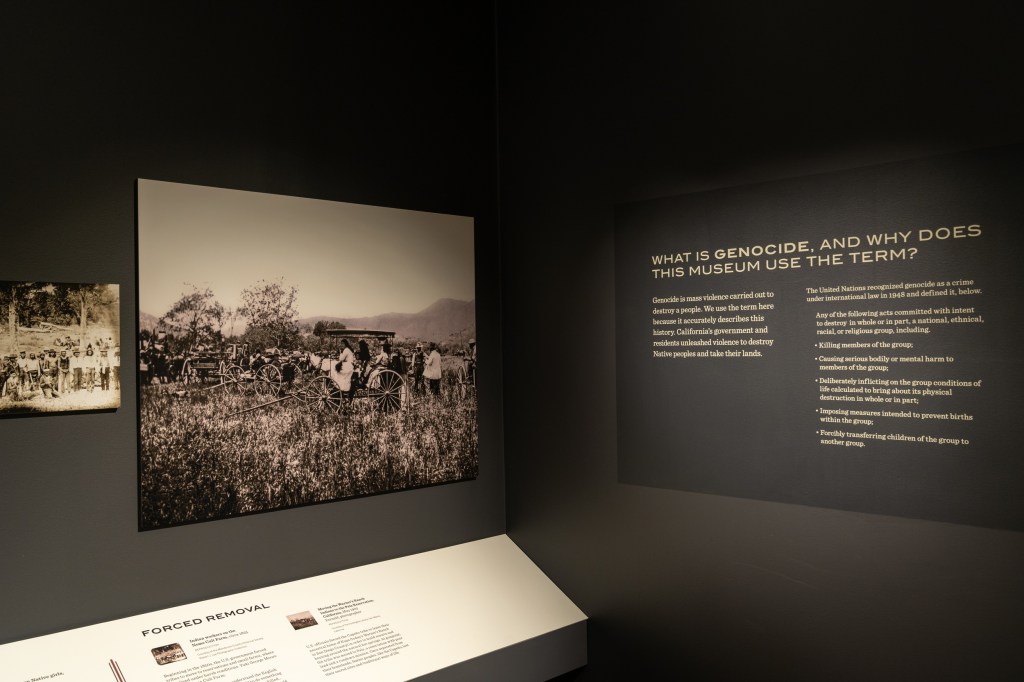

To be completely transparent with our visitors, we include this rationale—along with the United Nations’ definition of genocide—in large print on the wall. Genocide is mass violence carried out to destroy a people. In California, the government and residents unleashed violence to destroy Native peoples and take their lands. We deliberately use the term, because it accurately describes this history, and scholars are actively building a new vocabulary to talk about this history. Historians are always incorporating new information to help reframe historical narratives.

Collaborate with Native Advisors

It’s critical to include Native people in the development of exhibits about them—they are the experts. At OMCA we wouldn’t do it any other way. We have a Native Advisory Council (NAC) comprised of seven people from tribes across California, who convene on a regular basis for projects that are relevant to Native people. For this installation, we met with the entire group twice over the course of a year and contracted one advisor to review the exhibition text. The first meeting helped the exhibition team to finalize the focus. When we asked if we should frame the story as a genocide, we heard a unanimous, “Absolutely yes!”

“The majority of the people in the state learn about Indians in the 4th grade…. We need to make them understand that they’re a part of perpetuating a myth. They need to be digging out the truth, because most don’t tell you the truth. They avoid it. They whitewash it. They hide it. Or, they just lie about it. A lot of it is to protect the children. Well, my children live with it, too.”

In the second meeting, we presented them with the concept and rough sketches of the design. The drawings were sufficiently developed for a substantive response but they weren’t finalized, so we could incorporate the advisors’ feedback. Their initial response was positive but the design certainly needed tweaking. For instance, our early designs had the guns pointing down, to minimize potential negative reactions from visitors. The council encouraged us to display them pointing out, toward something, to reflect the violence they inflicted.

Our advisors were also key partners as we developed messages for the final section; many Native people are dedicated to revitalizing traditions and fighting for their rights. Our advisors also talked a lot about the responsibility of all people—Native and non-Native—to do this work for future generations.

“There’s a sense of responsibility…whether they’re Native or not…are they contributing to continuing erasure of Native peoples and cultures or are they supporting their futures?”

That responsibility may mean going out and joining the fight, but if visitors leave the installation and do nothing more than share this history with others, we have still succeeded.

I left that meeting thinking about my own responsibility. From the time I began work in museum education, I have been motivated to create spaces that lift up the voices of marginalized people, whether they are oppressed for reasons of age, gender, race, or class. So this idea that it’s actually a responsibility that anyone can assume resonates with me. What if all museum workers considered their responsibilities from a new vantage point? Maybe our visitors would be more likely to walk away feeling inspired to act, in large and small ways. History can teach us so much. It’s what I value most about working on projects like this one. Ultimately, it’s the words of our expert advisors that inspire me to carry on.

“Some people say it is a very deep spiritual thing…. You need that connection to the past, because the future generations are dependent on you, so you take that responsibility and you become part of that long line of people.”

“We are the ancestors of future generations”

Resources

Benjamin Madley, An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe (2016).

For further reading about decolonizing narratives and exhibit development practices, check out the MASS ACTION toolkit.

About the author:

Christine Lashaw has worked at the Oakland Museum of California (OMCA) for over 19 years, developing exhibits with community members. Currently, as an Experience Developer, she is a member of OMCA’s collaborative exhibit development team where she leads conversations and designs activities with diverse, local communities and co-designs immersive experiences for visitors. She is committed to engaging museum visitors with exhibits built around voices and stories that reflect their own experiences. She has a BFA from Rhode Island School of Design.

Skip over related stories to continue reading article

Comments