This article originally appeared in the January/February 2021 issue of Museum magazine, a benefit of AAM membership. In an effort to provide the broadest possible access to this critical topic, we are making these articles free and available to the public.

Make museum boards more inclusive and expertise-focused by disentangling giving and governance.

One of the flimsiest charges lodged against museums is that they are “elitist.” Out-of-context images of red-carpet museum fundraisers, or reports of millions paid for a precious painting or rare historical artifact, or merely a recitation of A-list contributors suggest that museums exclude everyday people so that they can cater to the whims of the wealthy.

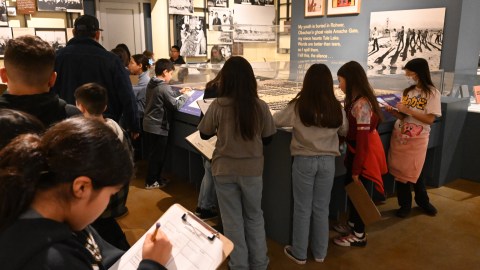

No, museums acquire objects of value from the private sector to make them accessible to the general public—be it for learning, cultural enrichment, or just plain enjoyment. They offer educational and cultural programs to schoolchildren, families, seniors, disadvantaged individuals, and the general public. Even when museums charge small fees, their programs and exhibitions normally operate at a financial loss unless a corporation, foundation, governmental agency, or generous patron underwrites the cost. Museums are voluntary versions of Robin Hood—converting resources of the rich to treasures for the poor, or middle class, or anyone else who chooses to participate.

But there is one place in our museums where inclusiveness seems an afterthought and where money has become more and more of an exclusionary barrier: the museum boardroom. Struggling for scarce resources to balance the annual budget and achieve the lofty milestones of a strategic plan—aspirational goals often stretched by ambitions of audience growth, collection expansion, and capital additions—museum leaders broaden the size of their governing boards and raise expectations for giving such that the overwhelming qualification for any member seems to have become the capacity to donate. This has implications.

A Look at Museum Boards

Museum boardrooms tend to be big. In a recent survey by the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD), 64 museums averaged 28.5 board members. The range varies widely, from a low of nine to a high of 98. While small museums tend to have fewer trustees, look up the boards of major art, history, or natural history museums, as well as many zoos, aquariums, and arboretums, and you might find 40, 50, 75, or even 100 members. After all, it must take many people to oversee such complex organizations. Or does it?

What about the largest corporations in the United States? Among the companies in the Dow Jones Industrial Average, it takes 12 board members to run Procter & Gamble, Coca-Cola, and 3M; 13 for ExxonMobil and Boeing; 10 for UnitedHealth and Visa. The largest board is Microsoft’s at 14; the smallest is Apple’s at seven. The average number of board members for all 30 Dow Jones companies is 11.36 at the time of this writing. The average board size of companies in the S&P 500 in 2019 was 10.7, and going back a full 10 years, it was 10.8. So the most efficient, profitable, and long-standing corporations in America govern themselves with a fraction of the board members seemingly required for a major museum.

“So where are the active or retired directors, museum CFOs, development directors, curators, and educators? Not on most museum boards, for sure.”

Who populates a board of directors in the for-profit world? In a word, experts. According to executive search and leadership consulting firm Spencer Stuart, active corporate leaders plus retirees make up 35 percent of S&P 500 boards, with another 27 percent representing the financial sector. Why? Because a corporate board requires expertise in order to maximize shareholder value, the absence of which could form the basis of a lawsuit for breach of fiduciary duty.

So where are the active or retired directors, museum CFOs, development directors, curators, and educators? Not on most museum boards, for sure. A few boards might have a retired museum professional—likely a former curator to advise on collections. Contemporary art museums, to their credit, offer seats to practicing artists. Normally, though, museum or collection expertise accounts for nowhere near the significant percentage of board seats allocated to experience in the for-profit world.

Corporate boards often struggle with issues of inclusion and diversity. Spencer Stuart’s survey indicates that only one in four corporate directors are women (26 percent), and minority representation averages only 19 percent for the 200 largest companies in the S&P 500. Museums practice better gender balance, with women representing 45 percent of board members, according to AAM’s comprehensive survey, Museum Board Leadership 2017: A National Report. The report revealed racial representation to be worse, as 89 percent of board members were identified as Caucasian with only 5 percent Black/African American and small percentages of Asians, Native Americans, and others. As for ethnicity, only 3.4 percent of museum board members were identified as Hispanic or Latino. And, disturbingly, in a nation where racial and ethnic minorities constitute 40 percent of the population, according to the United States Census Bureau, 46 percent of museum boards in the AAM survey self-identified as 100 percent white.

So why does it take two, three, or four times as many board members to govern a museum as an S&P 500 company? Why is expertise in running a museum not a significant requirement for a board that governs a museum? How in the public interest can a board represent its community when its members do not resemble the community? We know the answer, but it hides behind a façade of a fiduciary claim: that large museum boards have evolved to ensure the financial health of their organizations—so that boards may run their museums “more like a business.” The numbers suggest, however, that such boards do not run anything like a business and, for this reason, weaken the institutions they were organized to serve.

The Confluence of Giving and Governance

Museum boards are big because they conjoin the functions of giving and governance. This is not a cynical sacrifice of governance for giving, but a well-intentioned decision to benefit both. The executive is recruited for organizational expertise and for the prospect of a corporate gift. The banker and financier are valued for their fiscal savvy as well as for their access to programmatic underwriting. Legal experts and advertising executives bring valued experience and contribute essential pro bono services as well. Collectors offer content knowledge and the potential to donate their collections. Yes, philanthropists earn their places on nonprofit boards through their charitable giving, but I know from experience that they can be among the most sage advisers to the governing body, lending wisdom, purpose, encouragement, and long-term vision to the museum’s aspirational plans. These are good, caring, accomplished, bright, thoughtful, generous people.

“More board seats generate more giving, as each museum’s ambitions cause it to seek incremental funding wherever it can be found.”

More board seats generate more giving, as each museum’s ambitions cause it to seek incremental funding wherever it can be found. As the size of boards grows beyond corporate norms, however, the ability of any one person to influence real governance decreases because the number of people in the room exceeds the time available for every person to speak meaningfully on any topic, never mind debate the nuances of a contentious issue. This dilution means that expertise matters less as well, as do differing opinions pressed up against the constraints of timed agendas and the implied desire for consensus among the well-mannered majority.

Donors are entitled to direct their philanthropy to the programs and purposes they choose, even with conditions or requirements for recognition. Collection objects may come with restrictions. In exchange for their generosity, some donors expect a seat on the board and many museums are happy to offer one. A significant contribution earns the donor a vote on museum policies, budgets and operations. Donors parlay their legitimate rights to direct the purpose and expenditure of their gifts—conditions that museums have every right to accept or deny—into the ability to influence and direct how other people’s gifts may be spent—funds possibly aggregated over decades through endowments and amassed collectively each year through smaller contributions, memberships, grants, and earned revenues. This is how gifts are leveraged, extending the influence of a donation beyond the contribution itself. The notion that board seats belong to the largest donors is hardly ever challenged.

Except it is not true. The largest donor to the vast majority of museums in America is not considered automatically entitled to board representation. Who might that be? You and me: the American taxpayer. To encourage charitable giving to all qualified 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organizations, the US tax code allows contributors in the higher tax brackets to deduct somewhere between 32 percent and 37 percent of a gift’s value from their taxable income (percentages may be higher when state and local taxes apply). This means that a substantial portion of their gifts—from the value of collection objects, to cash donations, to gala tickets—comes from the coffers of the American public. Where are their seats on the board? What is their rightful representation in allocating the earnings of endowments accrued over generations, as well as revenues earned from payments by average people who visit the museum? Does it matter?

A Clash of Values

The governance model of American museums, in its current form, tends to favor growth and expansion. The businesspersons we recruit to our boards come from a world of competition. They increase sales and market share, competing to expand their commercial enterprises to ever more buying customers in the interest of enhancing shareholder value. This unchallenged assumption that museums must grow has placed oppressive pressure on museum leadership to make money: earn more net profits at the store; rent the facility; raise fees for services; “monetize” the collection via traveling exhibitions or through loan fees; recruit celebrity chefs to operate high-ticket restaurants; charge for special exhibitions; and raise general admission prices. In the world of business, this just makes sense, as corporate values equate success with increased visitation, program expansion, and earned revenues that rise quarter over quarter, fiscal year by fiscal year.

We who devote our careers to museums have come to live with corporate priorities in furtherance of our own values that prioritize community service, scholarship, learning, scientific knowledge, aesthetic excellence, empathy, fairness, inclusivity, and a sense of wonder. We see our museums as welcoming havens for those who might not otherwise come: people with disabilities, financial limitations, or other challenging circumstances. We provide exceptional services—classes, special tours, even outreach to group homes or school classrooms—and see ourselves, first and foremost, as caring, dedicated, and generous. We rely upon the fiduciary management of our boards to sustain our organizations in good times and bad. We accept salaries well below those in the for-profit sector for the privilege of working on behalf of our ideals, preserving our public treasures to educate, enlighten, and inspire communities year by year, generation by generation.

This coexistence of values is showing signs of strain. Probably the most talked-about issue for museums over recent years has been the urgent aspiration for them to become more diverse: places where people of differing races, ethnicities, ages, sexual orientations, gender identities, and all other manifestations of how people may be different can all feel welcome, in recognition of the way that all people are, fundamentally, the same. This has been an issue of fairness, shining a revealing light on the representational narrowness of collections and exhibitions; exclusionary nature of certain programs; uniformity in age and race of docents and volunteers; restricted opportunities for advancement and leadership on museum staffs; and, quite prominently, the lack of diversity on museum boards.

Frustration has spilt over into outrage when certain privileged members of the museum board are discovered to have amassed their wealth, and thus the source of their philanthropic gifts, by selling weapons of war, addictive pain killers, or fossil fuels. Staff protests, petitions, and the amplifying attention of the cultural media exposes such “toxic philanthropy,” providing cathartic relief each time a targeted culprit is outed and removed. But is the problem really corporate villains or the system that recruits them?

One of the most discouraging aspects of our governing status quo is that it places so many caring, generous, thoughtful, civically engaged volunteers in vulnerable positions of authority. To attain the recognition that their giving justifiably merits, we all but require donors to serve on museum boards. They should not be splattered by someone else’s “toxic” gift. Museums will always need the support of philanthropists, the underwriting of corporations, and the contributions of charitable foundations. The addictive reliance on trustee giving, however, has crowded our boardrooms with people from a narrow range of backgrounds because admission is restricted by the expectations of member gifts (a few exceptions notwithstanding). Fairness, access, and inclusivity are not aspirations that individual board members undervalue or overlook, but trustee means-testing leaves collective boards, in so many instances, lacking sufficient expertise and community-based perspective even to begin to meet the challenge that these ideals impose.

Reforms for Needed Change

To untangle the roles of giving and governance, museums must first establish and promote prestigious patron groups that rival the status of museum boards, bestowing generous donors with the accolades, camaraderie, access, and social stature that they deserve. Yes, such groups are exclusive by their cost of participation, but no more so than the annual gala or so many other museum events with fees attached. Universities regularly honor generous alumni by inviting them to a dean’s advisory council without any promise of a seat on the board of trustees.

We must also rethink the structure and composition of museum boards by adopting reforms that are rooted in the best practices of corporate governance, the tradition of American museums to honor patronage, and the fiduciary obligation of museums to serve their community constituents.

Downsize large museum boards to numbers conducive to participatory governance and in alignment with the best practices of the for-profit world. If 10 or 12 people can govern a major corporation, they can certainly conduct the fiduciary responsibilities of a museum.

Eliminate mandatory giving from the requirements of board service. What if we selected members on a wealth-blind basis? How might this group better reflect our population and the interests and aspirations of the people our museums were founded to serve?

Place museum professionals on museum boards. If corporate America relies on enterprise-specific expertise for half of its board membership, then a museum board without professional museum expertise cannot be exercising best practices.

Strengthen boards with local leaders who are truly qualified to speak on behalf of the diverse communities from which they come. Museums can enrich their governance with the wisdom of community leaders, such as educators and school administrators, academics, religious leaders, social service professionals, civil servants, nonprofit executives, and, yes, museum professionals. It can profit from the perspectives of racial and ethnic diversity, class differences, the LGBTQ+ community, and even a person or two from younger generations.

Nobody is banishing businesspersons, bankers, attorneys and philanthropists from service, but merely balancing them with people whose social connections, life experiences, and professional achievements more comprehensively represent the varied segments of their local communities—the corporate equivalent of consumer expertise. I hope that this helps us rebalance, as well, what we value as success, moving beyond the metrics of attendance and budget size to a broader embrace of sustainability, employee welfare, learning, cultural understanding, and inclusive welcome that may, over time, expand and grow the impact our museums make on people’s lives.

John Wetenhall is director of The George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum in Washington, DC. This article was adapted from a presentation written for Dumbarton Oaks’ symposium “Cultural Capital: Philanthropy in the Arts and Humanities Today,” postponed due to the pandemic.